In the Interest of the Netherlands

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Vision of the Army’, with Which the Royal Netherlands Army (RNLA) Steps Into the Future

Security through foresight The Royal Netherlands Army vision for the future Foreword Before you lies the ‘Vision of the Army’, with which the Royal Netherlands Army (RNLA) steps into the future. It has been written for everyone concerned with our security and is intended to promote dialogue about the future of our security apparatus. The world around us is changing at a rapid pace and that has consequences for the RNLA too. Take technological developments, for example, as a result of which land operations will fundamentally change, or the increasing interconnection between national and international security. Meanwhile, new threats are emerging and old threats are resurfacing. The protection of our territory and that of our NATO allies, for example, has faded into the background over the years. In recent years, however, the importance of this task has once again increased. Unlike our recent missions, our participation in this task is not optional. The RNLA must be there if needed. If it is to continue to play a decisive role in the future, the RNLA must be able to keep pace with the speed and unpredictability of change. It is not only the security situation that is volatile. Climate change, energy scarcity, demographic trends and economic stability all contribute to the unpredictability of the future. All of this has far- reaching consequences for our organisation and the manner in which we work. If the RNLA is to continue protecting what is dear to us all, we will have to make some fundamental changes. In the 2018 Defence White Paper, the impetus was given for the broad lines of development of the Netherlands armed forces. -

200227 Liberation Of

THE LIBERATION OF OSS Leo van den Bergh, sitting on a pile of 155 mm grenades. Photo: City Archives Oss 1 September 2019, Oss 75 Years of Freedom The Liberation of Oss Oss, 01-09-2019 Copyright Arno van Orsouw 2019, Oss 75 Years of Freedom, the Liberation of Oss © 2019, Arno van Orsouw Research on city walks around 75 years of freedom in the centre of Oss. These walks have been developed by Arno van Orsouw at the request of City Archives Oss. Raadhuislaan 10, 5341 GM Oss T +31 (0) 0412 842010 Email: [email protected] Translation checked by: Norah Macey and Jos van den Bergh, Canada. ISBN: XX XXX XXXX X NUR: 689 All rights reserved. Subject to exceptions provided by law, nothing from this publication may be reproduced and / or made public without the prior written permission of the publisher who has been authorized by the author to the exclusion of everyone else. 2 Foreword Liberation. You can be freed from all kinds of things; usually it will be a relief. Being freed from war is of a different order of magnitude. In the case of the Second World War, it meant that the people of Oss had to live under the German occupation for more than four years. It also meant that there were men and women who worked for the liberation. Allied forces, members of the resistance and other groups; it was not without risk and they could lose their lives from it. During the liberation of Oss, on September 19, 1944, Sergeant L.W.M. -

Quarterly Aviation Report

Quarterly Aviation Report DUTCH SAFETY BOARD page 14 Investigations Within the Aviation sector, the Dutch Safety Board is required by law to investigate occurrences involving aircraft on or above Dutch territory. In addition, the Board has a statutory duty to investigate occurrences involving Dutch aircraft over open sea. Its October - December 2020 investigations are conducted in accordance with the Safety Board Kingdom Act and Regulation (EU) In this quarterly report, the Dutch Safety Board gives a brief review of the no. 996/2010 of the European past year. As a result of the COVID-19 pandemic, the number of commercial Parliament and of the Council of flights in the Netherlands was 52% lower than in 2019. The Dutch Safety 20 October 2010 on the Board therefore received fewer reports. In 2020, 27 investigations were investigation and prevention of started into serious incidents and accidents in the Netherlands. In addition, accidents and incidents in civil the Dutch Safety Board opened an investigation into a serious incident aviation. If a description of the involving a Boeing 747 in Zimbabwe in 2019. The Civil Aviation Authority page 7 events is sufficient to learn of Zimbabwe has delegated the entire conduct of the investigation to the lessons, the Board does not Netherlands, where the aircraft is registered and the airline is located. In the conduct any further investigation. past year, the Dutch Safety Board has offered and/or provided assistance to foreign investigative bodies thirteen times in investigations involving Dutch The Board’s activities are mainly involvement. aimed at preventing occurrences in the future or limiting their In this quarterly report you can read, among other things, about an consequences. -

The Art of Staying Neutral the Netherlands in the First World War, 1914-1918

9 789053 568187 abbenhuis06 11-04-2006 17:29 Pagina 1 THE ART OF STAYING NEUTRAL abbenhuis06 11-04-2006 17:29 Pagina 2 abbenhuis06 11-04-2006 17:29 Pagina 3 The Art of Staying Neutral The Netherlands in the First World War, 1914-1918 Maartje M. Abbenhuis abbenhuis06 11-04-2006 17:29 Pagina 4 Cover illustration: Dutch Border Patrols, © Spaarnestad Fotoarchief Cover design: Mesika Design, Hilversum Layout: PROgrafici, Goes isbn-10 90 5356 818 2 isbn-13 978 90 5356 8187 nur 689 © Amsterdam University Press, Amsterdam 2006 All rights reserved. Without limiting the rights under copyright reserved above, no part of this book may be reproduced, stored in or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means (electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise) without the written permission of both the copyright owner and the author of the book. abbenhuis06 11-04-2006 17:29 Pagina 5 Table of Contents List of Tables, Maps and Illustrations / 9 Acknowledgements / 11 Preface by Piet de Rooij / 13 Introduction: The War Knocked on Our Door, It Did Not Step Inside: / 17 The Netherlands and the Great War Chapter 1: A Nation Too Small to Commit Great Stupidities: / 23 The Netherlands and Neutrality The Allure of Neutrality / 26 The Cornerstone of Northwest Europe / 30 Dutch Neutrality During the Great War / 35 Chapter 2: A Pack of Lions: The Dutch Armed Forces / 39 Strategies for Defending of the Indefensible / 39 Having to Do One’s Duty: Conscription / 41 Not True Reserves? Landweer and Landstorm Troops / 43 Few -

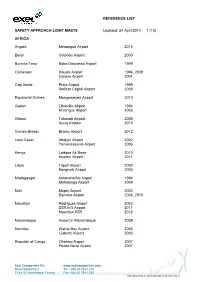

Reference List Safety Approach Light Masts

REFERENCE LIST SAFETY APPROACH LIGHT MASTS Updated: 24 April 2014 1 (10) AFRICA Angola Menongue Airport 2013 Benin Cotonou Airport 2000 Burkina Faso Bobo Diaulasso Airport 1999 Cameroon Douala Airport 1994, 2009 Garoua Airport 2001 Cap Verde Praia Airport 1999 Amilcar Capral Airport 2008 Equatorial Guinea Mongomeyen Airport 2010 Gabon Libreville Airport 1994 M’vengue Airport 2003 Ghana Takoradi Airport 2008 Accra Kotoka 2013 Guinea-Bissau Bissau Airport 2012 Ivory Coast Abidjan Airport 2002 Yamoussoukro Airport 2006 Kenya Laikipia Air Base 2010 Kisumu Airport 2011 Libya Tripoli Airport 2002 Benghazi Airport 2005 Madagasgar Antananarivo Airport 1994 Mahajanga Airport 2009 Mali Moptu Airport 2002 Bamako Airport 2004, 2010 Mauritius Rodrigues Airport 2002 SSR Int’l Airport 2011 Mauritius SSR 2012 Mozambique Airport in Mozambique 2008 Namibia Walvis Bay Airport 2005 Lüderitz Airport 2005 Republic of Congo Ollombo Airport 2007 Pointe Noire Airport 2007 Exel Composites Plc www.exelcomposites.com Muovilaaksontie 2 Tel. +358 20 754 1200 FI-82110 Heinävaara, Finland Fax +358 20 754 1330 This information is confidential unless otherwise stated REFERENCE LIST SAFETY APPROACH LIGHT MASTS Updated: 24 April 2014 2 (10) Brazzaville Airport 2008, 2010, 2013 Rwanda Kigali-Kamombe International Airport 2004 South Africa Kruger Mpumalanga Airport 2002 King Shaka Airport, Durban 2009 Lanseria Int’l Airport 2013 St. Helena Airport 2013 Sudan Merowe Airport 2007 Tansania Dar Es Salaam Airport 2009 Tunisia Tunis–Carthage International Airport 2011 ASIA China -

What Happens Next? Life in the Post-American World JANUARY 2014 VOL

Will mankind ARMED, DANGEROUS The reason New ‘solution’ to ever reach Europe has a lot more for world family problems: the stars? nukes than you think troubles Don’t have kids THE PHILADELPHIA TRUMPETJANUARY 2014 | thetrumpet.com What Happens Next? Life in the post-American world JANUARY 2014 VOL. 25, NO. 1 CIRC. 325,015 THE DANGER ZONE T A member of the German Air Force based in Alamogordo, New Mexico, prepares a Tornado aircraft for takeoff. How naive is America to entrust this immense firepower to nations that so recently—and throughout history— have proved to be enemies of the free world. WORLD COVER SOCIETY 1 FROM THE EDITOR Europe’s 20 How Did Family Get Nuclear Secret 2 What Happens After So Complicated? 18 INFOGRAPHIC American B61 a Superpower Dies? 34 SOCIETYWATCH Thermonuclear Weapons in The world is about to find out. Europe SCIENCE 23 Will Mankind Ever Reach 26 WORLDWATCH Unifying 7 Conquering the Holy Land the Stars? Europe’s military—through The cradle of civilization, the stage of the Crusades, the most contested the back door • North Africa’s territory on Earth—who will gain control now that America is gone? policeman • Is the president BIBLE purging the military of 31 PRINCIPLES OF LIVING 10 dissenters • Don’t underrate The World’s Next Superpower Mankind’s Aversion Therapy 12 Partnering with Latin America al Shabaab • No prize for you • Lesson 13 Africa’s powerful neighbor Moscow puts Soviet squeeze 35 COMMENTARY A Warning on neighbor nations of Hope 14 Czars and Emperors COVER If the U.S. -

The Future of European Naval Power and the High-End Challenge Jeremy Stöhs

Jeremy Stöhs ABOUT THE AUTHOR Dr. Jeremy Stöhs is the Deputy Director of the Austrian Center for Intelligence, Propaganda and Security Studies (ACIPSS) and a Non-Resident Fellow at the Institute for Security Policy, HOW HIGH? Kiel University. His research focuses on U.S. and European defence policy, maritime strategy and security, as well as public THE FUTURE OF security and safety. EUROPEAN NAVAL POWER AND THE HIGH-END CHALLENGE ISBN 978875745035-4 DJØF PUBLISHING IN COOPERATION WITH 9 788757 450354 CENTRE FOR MILITARY STUDIES How High? The Future of European Naval Power and the High-End Challenge Jeremy Stöhs How High? The Future of European Naval Power and the High-End Challenge Djøf Publishing In cooperation with Centre for Military Studies 2021 Jeremy Stöhs How High? The Future of European Naval Power and the High-End Challenge © 2021 by Djøf Publishing All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means – electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise – without the prior written permission of the Publisher. This publication is peer reviewed according to the standards set by the Danish Ministry of Higher Education and Science. Cover: Morten Lehmkuhl Print: Ecograf Printed in Denmark 2021 ISBN 978-87-574-5035-4 Djøf Publishing Gothersgade 137 1123 København K Telefon: 39 13 55 00 e-mail: [email protected] www. djoef-forlag.dk Editors’ preface The publications of this series present new research on defence and se- curity policy of relevance to Danish and international decision-makers. -

Virtual Mission and Training Areas at the Dutch Land Training Centre

Virtual Mission and Training Areas at the Dutch Land Training Centre Science and Innovation Interoperable by Design at the Front Line Marco Welleman Frido Kuijper Royal Netherlands Army TNO Land Training Centre Defence, Security Simulation Centre Land Warfare and Safety ITEC, Stockholm, mei 2019 Mission Simulation Centre Land Warfare • Support our troops by improving the quality of their education and training • Support our commanders by improving the quality of their decision-making (process) • Contribute to the acquisition of new materiel and the development of new concepts • Subject matter expert for knowledge and innovation for simulation 2 Royal Netherlands Army Simulation Centre Land Warfare Organization RNLA CLAS OTCO LTC SIMCEN EC-SIM MCTC SG TACTIS CST EC-SIM 92 FTEs M&S A&A CM KKW-Sim R&D 3 Royal Netherlands Army Simulation Centre Land Warfare Simulation suite Live Virtual Constructive KKW - VBS3 & MCTC SUIT TACTIS CST Sim SB Pro (SAAB) (Re-Lion) (THALES) (ELBIT) (THALES) (Bohemia Int, eSim Games) C2 SYSTEM / ELIAS (BMS) Terraindatabase 3D Entities Scenario’s l ORBAT Data Bases 4 Royal Netherlands Army Simulation Centre Land Warfare Mobile Combat Training Level 3-5 Centre (MCTC) 5 Royal Netherlands Army Simulation Centre Land Warfare Small Arms Shooting Simulator Level 1 6 Royal Netherlands Army Simulation Centre Land Warfare Small Unit Immersive Trainer Level 2 (SUIT) 7 Royal Netherlands Army Simulation Centre Land Warfare Driving simulator Level 1 8 Royal Netherlands Army Simulation Centre Land Warfare FAC Trainer Level 1-2 -

Strengths and Weaknesses of the Netherlands Armed Forces a Strategic Survey

THE ARTS This PDF document was made available from www.rand.org as a public CHILD POLICY service of the RAND Corporation. CIVIL JUSTICE EDUCATION ENERGY AND ENVIRONMENT Jump down to document6 HEALTH AND HEALTH CARE INTERNATIONAL AFFAIRS The RAND Corporation is a nonprofit research NATIONAL SECURITY POPULATION AND AGING organization providing objective analysis and effective PUBLIC SAFETY solutions that address the challenges facing the public SCIENCE AND TECHNOLOGY and private sectors around the world. SUBSTANCE ABUSE TERRORISM AND HOMELAND SECURITY TRANSPORTATION AND INFRASTRUCTURE Support RAND WORKFORCE AND WORKPLACE Browse Books & Publications Make a charitable contribution For More Information Visit RAND at www.rand.org Explore RAND Europe View document details Limited Electronic Distribution Rights This document and trademark(s) contained herein are protected by law as indicated in a notice appearing later in this work. This electronic representation of RAND intellectual property is provided for non-commercial use only. Unauthorized posting of RAND PDFs to a non-RAND Web site is prohibited. RAND PDFs are protected under copyright law. Permission is required from RAND to reproduce, or reuse in another form, any of our research documents for commercial use. For information on reprint and linking permissions, please see RAND Permissions. This product is part of the RAND Corporation technical report series. Reports may include research findings on a specific topic that is limited in scope; present discus- sions of the methodology employed in research; provide literature reviews, survey instruments, modeling exercises, guidelines for practitioners and research profes- sionals, and supporting documentation; or deliver preliminary findings. All RAND reports undergo rigorous peer review to ensure that they meet high standards for re- search quality and objectivity. -

United States Nuclear Weapons in Europe

United States nuclear CND weapons in Europe Around 200 United States nuclear B61 free-fall gravity bombs are stationed in five countries in Europe: Belgium, Germany, the Netherlands, Italy and Turkey. While the governments of these countries have never officially declared the presence of these G weapons, individuals such as the former Italian president and former Dutch prime minister have confirmed this to be the case. HE nuclear sharing arrangement is part of the Non-Proliferation Treaty (NPT). Articles 1 and 2 of N North Atlantic Treaty Organisation’s (NATO) the NPT forbid the transfer of nuclear weapons to T defence policy. In peace time, the nuclear non-nuclear weapon states, but Belgium, Germany, the weapons stored in non-nuclear countries are guarded Netherlands, Italy and Turkey are all non-nuclear. I by US forces, with a dual code system activated in a time of war. Both host country and the US would Even though the UK does not host US bombs any then need to approve the use of the weapons, which more, the UK’s nuclear weapons system has been F would be launched on the former’s airplanes. assigned to NATO since the 1960s. Ultimately, this means that the UK’s nuclear weapons could be used When these bombs were initially deployed, the original against a country attacking (or threatening to attack) targets were eastern European states. But as the Cold one of the alliance member states since an attack on War ended, and these states became part of the one NATO member state is seen as being an attack on E European Union and in some cases NATO itself, the all member states. -

NL-ARMS O;Cer Education

NL-ARMS Netherlands Annual Review of Military Studies 2003 O;cer Education The Road to Athens! Harry Kirkels Wim Klinkert René Moelker (eds.) The cover image of this edition of NL-ARMS is a photograph of a fragment of the uni- que ‘eye tiles’, discovered during a restoration of the Castle of Breda, the home of the RNLMA. They are thought to have constituted the entire floor space of the Grand North Gallery in the Palace of Henry III (1483-1538). They are attributed to the famous Antwerp artist Guido de Savino (?-1541). The eyes are believed to symbolize vigilance and just government. NL-Arms is published under the auspices of the Dean of the Royal Netherlands Military Academy (RNLMA (KMA)). For more information about NL-ARMS and/or additional copies contact the editors, or the Academy Research Centre of the RNLMA (KMA), at adress below: Royal Netherlands Military Academy (KMA) - Academy Research Centre P.O. Box 90.002 4800 PA Breda Phone: +31 76 527 3319 Fax: +31 76 527 3322 NL-ARMS 1997 The Bosnian Experience J.L.M. Soeters, J.H. Rovers [eds.] 1998 The Commander’s Responsibility in Difficult Circumstances A.L.W. Vogelaar, K.F. Muusse, J.H. Rovers [eds.] 1999 Information Operations J.M.J. Bosch, H.A.M. Luiijf, A.R. Mollema [eds.] 2000 Information in Context H.P.M. Jägers, H.F.M. Kirkels, M.V. Metselaar, G.C.A. Steenbakkers [eds.] 2001 Issued together with Volume 2000 2002 Civil-Military Cooperation: A Marriage of Reason M.T.I. Bollen, R.V. -

And Why It Matters for the Netherlands

operationeel and why it matters for the netherlands Mr. Theo Sierksma (Rohde & Schwarz Benelux – RSBNL) and Mr. Michael Rother (Rohde & Schwarz GmbH) On May 17, 2018 the Defense Ministers of the Netherlands and Germany met in Lohheide in Lower Saxony (Germa- ny), the base of the mixed Tank Battalion 414. Both Minis- ters of Defense signed a Letter of Intent to join efforts in digitalization of their land forces for gapless communica- tion and interoperability. Over the last few months, there is a lot of attention in the Dutch Ministry of Defense organiza- tion for the program FOXTROT. Recently the program proposal has been approved (see INTERCOM 46.3-2017) and the organization is currently working on the composition of the program team. This team will also include a liaison officer with the German program D-LBO, before known as MoTaKo (Mobile Taktische Kommunikation). Although the digitization of mobile tactical communication is a huge program in Germany, in terms of material and financial size, there are still lots of decisions pending. This article will inform about the program MoTaKo and also indicate the coherence and similarities with the Netherlands program FOXTROT. intercom | jaargang 47 | 2 43 operationeel Why is an update needed? Most tactical radio’s in the German Bundeswehr are from early 90s (mostly unencrypted and analog). The current means are obsolete and no longer suited to enable modern communi- cation on the tactical mobile battlefield: difficult to maintain, no simultaneously voice and data, limited bandwidth, no IP capabilities, not multi-national interoperable, etc. In addition, various German military units have been integrated into multinational forces commands in the recent years, but not backed by adequate procurements/solutions to enable ro- bust military operations in this joint and combined way.