Spring 2018 34

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

“The Black Mecca.”

“The Black Mecca.” Gentrification in Black Central Harlem and its Complex Socio- Cultural Consequences. Author: Ine Sijberts Student Number Author: 4377761 Institution: Radboud Universiteit Nijmegen Department: Department of North-American Studies Date of Delivery: July 16, 2018 Supervisor: Dr. Dario Fazzi Email: [email protected] Second Reader: Dr. M. Roza Email: [email protected] MA Thesis / Sijberts, I. / s4377761 /2 ENGELSE TAAL EN CULTUUR Teacher who will receive this document: Dr. Dario Fazzi Title of document: “The Black Mecca.” Gentrification in Black Central Harlem and its Complex Socio-Cultural Consequences. Name of course: Master Thesis North American Studies Date of submission: 16-07-2018 Word count: 25.037 The work submitted here is the sole responsibility of the undersigned, who has neither committed plagiarism nor colluded in its production. Signed Name of student: Ine Sijberts Student number: 4377761 MA Thesis / Sijberts, I. / s4377761 /3 Abstract Much of the literature on gentrification is written from an economic perspective, with many different sub-discussions within the larger gentrification debate. Research done through a social and cultural lens is mostly absent within these discussions. This thesis therefore sets out to clarify the main socio-cultural consequences of gentrification in black neighborhoods, taking Central Harlem as its main case study. Through a multidisciplinary framework this thesis positions itself at the crossroad of the social, cultural and political history fields. First, this thesis will start off with an explanation on gentrification and its deep connection with displacement practices. Next, it will address the relationship between gentrification and crime with a particular focus on race. -

Download Download

HAS THE PAST PASSED? ON THE ROLE OF HISTORIC MEMORY IN SHAPING THE RELATIONS BETWEEN AFRICAN AMERICANS AND CONTEMPORARY AFRICAN MIGRANTS IN THE USA • DMITRI M. BONDARENKO • ABSTRACT ............................................................................................................................................... African Americans and contemporary African migrants to the USA do not form a single ‘Black community’. Their relations are characterized by simultaneous mutual attraction and repulsion. Based on field evidence, the article discusses the role played in it by the reflection in historic memory and place in mass consciousness of African Americans and African migrants of key events in Black American and African history: transatlantic slave trade, slavery, its abolition, and the Civil Rights Movement in the US, colonialism, anticolonial struggle, and the fall of apartheid regime in South Africa. It is shown that they see the key events of the past differently, and different events are seen as key by each group. Collective historic memory works more in the direction of separating the two groups from each other by generating and supporting contradictory or even negative images of mutual perception. ............................................................................................................................................... Keywords: African Americans, African migrants, USA, historic memory, intercultural interaction, mass consciousness Introduction1 In the 17th–19th centuries, in most countries of the New -

Retaking Mecca: Healing Harlem Through Restorative Just Compensation

Retaking Mecca: Healing Harlem through Restorative Just Compensation MERON WERKNEH* Neighborhood redevelopment often brings about major cultural shifts. The Fifth Amendment‟s Takings Clause allows for the taking of private property only when it is for public use, and requires just compensation. Courts have expanded the “public use” requirement to allow “urban renewal projects” where the economic development of the area stands as the public purpose. The consequent influx of private developers in the name of economic revitalization has led to the displacement of many communities — particularly those made up of low-income people of color. This displacement has been extremely visible in Harlem. Harlem was once considered the Mecca of black art and culture, but the last few decades have brought changes that may cost it this title. Rampant land condemnations and redevelopment efforts incited a noticeable socioeconomic shift in the historic neighborhood. Residents and small business owners pushed against these eminent domain actions, but to no avail — Harlem‟s gentrification continued. Rising rents and institutional barriers compelled the slow exodus of longtime African American residents and business owners unable to afford the increasing costs. This Note explores the expansion of “public use” after Kelo v. City of New London, noting how it encouraged gentrification, particularly in Harlem. It argues that the current compensation scheme does not meet the constitutional standard of being “just” because it does not account for the loss of the community as a unit, or the dignitary harm suffered due to forcible displacement in the name of “revitalization.” Finally, it proposes Community Benefits Agreements as the vehicles through which gentrifying communities can receive restorative compensation, offering recommendations for creating a CBA that could begin to heal Harlem. -

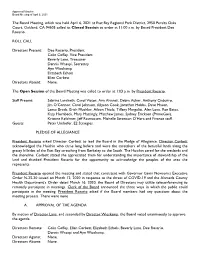

Board Meeting Minutes

Approved Minutes Board Meeting of April 6, 2021 The Board Meeting, which was held April 6, 2021 at East Bay Regional Park District, 2950 Peralta Oaks Court, Oakland, CA 94605 called its Closed Session to order at 11:00 a.m. by Board President Dee Rosario. ROLL CALL Directors Present: Dee Rosario, President Colin Coffey, Vice President Beverly Lane, Treasurer Dennis Waespi, Secretary Ayn Wieskamp Elizabeth Echols Ellen Corbett Directors Absent: None. The Open Session of the Board Meeting was called to order at 1:03 p.m. by President Rosario. Staff Present: Sabrina Landreth, Carol Victor, Ana Alvarez, Debra Auker, Anthony Ciaburro, Jim O’Connor, Carol Johnson, Allyson Cook, Jonathan Hobbs, Dave Mason, Lance Brede, Erich Pfuehler, Aileen Thiele, Tiffany Margulici, Alan Love, Ren Bates, Katy Hornbeck, Mary Mattingly, Matthew James, Sydney Erickson (PrimeGov), Kristine Kelchner, Jeff Rasmussen, Michelle Strawson O’Hara and Finance staff. Guests: Peter Umhofer, E2 Straegies. PLEDGE OF ALLEGIANCE President Rosario asked Director Corbett to lead the Board in the Pledge of Allegiance. Director Corbett acknowledged the Huichin who came long before and were the caretakers of the beautiful lands along the grassy hillsides of the East Bay stretching from Berkeley to the South. The Huichin cared for the wetlands and the shoreline. Corbett stated she appreciated them for understanding the importance of stewardship of the land and thanked President Rosario for the opportunity to acknowledge the peoples of the area she represents. President Rosario opened the meeting and stated that consistent with Governor Gavin Newsom’s Executive Order N-25-20 issued on March 12, 2020 in response to the threat of COVID-19 and the Alameda County Health Department’s Order dated March 16, 2020, the Board of Directors may utilize teleconferencing to remotely participate in meetings. -

Situation (Intentionality and Gender)

128 ISLAMIC AFRICA situation (intentionality and gender). The case of Mariam and Abdulma- lik, which is at the center of this dispute over intent to divorce (and which appears in different moments throughout the book), highlights gendered agency at work in the vein of Susan Hirsch, Judith Tucker, Laura Fair, and Ziba Mir- Hosseini. An Islamic Court in Context contributes new case studies to support established theoretical claims regarding the situated process of Islamic le- gal reasoning and the importance of attending to gender roles and perfor- mance in Islamic family courts. At times, the book reads very much like its original dissertation form, which does not serve the strength of the original contributions that Stiles is making (again, her points on intentionality are quite compelling). Stiles’s arguments about the intersection of document production, gender position, and judicial reasoning could be drawn to the fore in more substantial ways throughout the chapters. The book’s market price at $95.00 is near prohibitive, making it diffi cult to assign the mono- graph in classes. Still, Erin Stiles presents some useful points of analysis and observation of the situated meaning of judicial reasoning in an Islamic court, and this reader looks forward to more from Stiles in the future. Emily Burrill, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill Zain Abdullah. Black Mecca: The African Muslims of Harlem. New York: Oxford University Press, 2010. Pp. viii, 294. $35.00 “The morning air crackles with excitement as the courtyard at the Har- lem State Offi ce Building swells with hundreds of African Muslims— men, women, and children decked out in their best boubou wear and head- wraps. -

Structural Barriers to Racial Equity in Pittsburgh Expanding Economic Opportunity for African American Men and Boys

RESEARCH REPORT Structural Barriers to Racial Equity in Pittsburgh Expanding Economic Opportunity for African American Men and Boys Margaret C. Simms Marla McDaniel Saunji D. Fyffe Christopher Lowenstein October 2015 ABOUT THE URBAN INSTITUTE The nonprofit Urban Institute is dedicated to elevating the debate on social and economic policy. For nearly five decades, Urban scholars have conducted research and offered evidence-based solutions that improve lives and strengthen communities across a rapidly urbanizing world. Their objective research helps expand opportunities for all, reduce hardship among the most vulnerable, and strengthen the effectiveness of the public sector. ABOUT THE HEINZ ENDOWMENTS Primary funding for this report was provided by The Heinz Endowments, which supports efforts to make southwestern Pennsylvania a premier place to live and work, a center for learning and educational excellence, and a region that embraces diversity and inclusion. Copyright © October 2015. Urban Institute. Permission is granted for reproduction of this file, with attribution to the Urban Institute. Contents Acknowledgments iv Executive Summary v Structural Barriers vi Conclusion vii Introduction 1 Study Concept and Design 4 Applying a Structural Barriers Perspective 4 Tasks Undertaken 5 Organization of the Report 7 The Economic Position of African American Men in Pittsburgh 9 The Data 9 Experiences of African American Men 11 Why Now: Themes from Interviews about the Perceived Urgency for Better Inclusion 14 Barriers to Economic Advancement 16 -

Is Neutral the New Black?: Advancing Black Interests Under the First Black Presidents

IS NEUTRAL THE NEW BLACK?: ADVANCING BLACK INTERESTS UNDER THE FIRST BLACK PRESIDENTS An undergraduate thesis presented by SAMANTHA JOY FAY Submitted to the Department of Political Science of Haverford College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of BACHELOR OF ARTS IN POLITICAL SCIENCE Advised by Professor Stephen J. McGovern April 2014 Copyright © 2014 Samantha Joy Fay All Rights Reserved 2 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS First, I am eternally grateful to God for giving me the strength to get through this process, especially when I did not think I had it in me to keep going. If nothing else, writing this has affirmed for me that through Him all things are possible. To God be the glory. Second, thank you to everyone who contributed to my research, especially my advisor. It would take far too long for me to name all of you, and I would hate to forget someone, so I hope it will suffice to say that I am indebted to you for the time and effort you expended on my behalf. Third, I have to give a shout-out to my friends. I have neglected you in the worst way this year, but I am so grateful for the distractions from the misery of work, your attempts to stay up as late as I do (nice try), and most of all your understanding. I really do appreciate you, your encouraging words, your shared cynicism, and your hugs. I hope this makes up for me not being able to show it as much as I wanted to this year. -

WHY AFRICAN-AMERICANS? Are Less Likely to Play Than Many Other Groups

AFRICAN-AMERICAN ENGAGEMENT GUIDE EMBRACE THE FUTURE OF THE GAME 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS 8 9 1. What We Believe 6. Putting Your Plan in Place 2. The Opportunity 7. Partner Up 3. Demographics 8. Cultural Cues 4. Coaching Success Stories 9. Connecting 5. Getting Started 1 WE BELIEVE IN AN OPEN GAME At the USTA, we celebrate the open format — the idea that anyone from anywhere should be able to play and compete equally and fairly in a sport that is inclusive and welcoming to all. That’s the principle behind our signature tournament, the US Open. It’s also the driving force behind our Diversity & Inclusion Strategy, which is designed to grow and promote our sport to the next generation of fans, players and volunteers and to make sure that the face of tennis reflects the face of our country. To do that, we are removing barriers and creating opportunities wherever we can, so that tennis becomes a true reflection of all of America. Our mission is to position the USTA and the sport of tennis as the global model for diversity and inclusion in sports. And the first step in that mission starts right here with you. This guide is designed to help you connect with a key segment vital At the USTA, we want the game of tennis and the to the growth of tennis: African-Americans. You’ll learn about African- tennis courts across this country to reflect the American demographics, history with the sport, steps for engagement unique diversity that makes America great. and success stories from others. -

Harlem Renaissance New York: 1920’S-1930’S History

The Harlem Renaissance New York: 1920’s-1930’s History History • 5 Burrows of NY: • Bronx • Brooklyn • Manhattan • Queens • Staten Island • Harlem is the northern section of Manhattan History •Post-Civil War: blacks were free to live wherever they wanted. •The Great Migration: Early 1900’s. Many African-Americans were moving north to work in industrial cities •1915: About 50,000 African- Americans lived in Harlem •1930: Increased to 150,000 History • The Harlem Renaissance was originally called “The New Negro Movement” • “The New Negro” was a term used to refer to blacks who wanted to prove they were just as intelligent & creative as whites History • The purpose of the movement: • to prove that African- Americans could create great literature, music, & art History • After WWI, Americans did not have to be frugal. • Now it was ok to have excess • Economic boom • Extra money to spend on arts & entertainment • Would lead to the “Roaring 20’s” History • 1919: 18th Amendment Passed • Prohibition • Led to “Speakeasies” & other secret establishments to socialize, drink, rebel • (repealed in 1933) • 21st Amendment History • Whites could commit 2 taboos at once.... • Drink alcohol • Mingle with blacks • Led to famous whites enjoying & promoting black artists • They realized that black culture was fun. History • Summer 1919 • Called “Red Summer” • Hundreds of Race Riots across US. • Bloody & widely documented in press History • "The National Association for the Advancement of Colored People respectfully enquires how long the Federal Government under your administration intends to tolerate anarchy in the United States?” • telegram from NAACP to President Woodrow Wilson • 1919 Literature W.E.B. -

Freaknik and the Civil Rights Legacy of Atlanta by Peter William Stockus

Rethinking African American Protest: Freaknik and the Civil Rights Legacy of Atlanta by Peter William Stockus A thesis submitted to the Graduate Faculty of Auburn University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts Auburn, Alabama December 8, 2012 Keywords: Atlanta, Georgia, Civil Rights, Hip-Hop, Protest, Social Copyright 2012 by Peter William Stockus Approved by David Carter, Chair, Associate Professor of History Aaron Shapiro, Assistant Professor of History Charles Israel, Associate Professor of History Abstract During the late 1980s and early 90s, Atlanta played host to the spring break festival Freaknik. A gathering of Historically Black College and University students and African American youth, Freaknik came to challenge the racial dynamics of a city that billed itself as “too busy to hate.” As black revelers cruised the streets, the congregation of up to 250,000 youth created major logistical problems for the city and forced the residents of the predominantly white neighborhoods of Piedmont Park and Midtown to examine the racial dynamics of Atlanta. These contested neighborhoods became hotbeds of protest, with many white residents viewing the actions of the fete participants as damaging to the neighborhoods. While many within Atlanta’s white community opposed the party, leaders of the black community condemned the actions of African American Mayor Bill Campbell and the white populace for restricting Freaknik, suggesting the actions of Freaknik opponents as racist and unnecessary. Utilizing Atlanta’s Civil Rights legacy, Freaknik participants not only confronted contested spaces of community within Atlanta, but also disputed the ownership of the Civil Rights movement. -

Channon Miller African American Studies Essay Competition Graduate Student Submission May 2, 2014

Channon Miller African American Studies Essay Competition Graduate Student Submission May 2, 2014 Mothering Across Fragmented Borders of Blackness: Cross-Ethnic Ties Among African Immigrant, Caribbean Immigrant and African American Mothers Situated in Hartford, Connecticut’s Albany Avenue, behind an African Methodist Episcopal Church and beneath the shadow of the large golden arches of a McDonald’s logo, is Bravo Plaza. Lori’s African Hair Braiding Boutique, Miller’s Caribbean Grocery Store, “Golden Krust” Beef Patties, Coconut’s Jewelry Warehouse and a Haitian-American owned dry cleaning service, line the perimeters of this small, public square. In the surrounding parking lot, friends and family members gather for small talk, social event promoters distribute fliers to patrons and the rhythms of Soca, Hip Hop and Reggae blast from the car stereos while their passengers indulge in fries, a Beef Patty or West Indian soda pop. When viewed in light of the prevailing discourse on today’s black immigrants, this center of cultural and commercial activity in Hartford’s north end emerges as a place of discord. Newspaper and social media headlines such as, “Fighting for the Crumbs: African Americans vs. Black Immigrants,” “African Immigrants Want No Community with African Americans” and “Caribbean Roots Tangle with African Americans in the U.S.,” bring to the fore an image of African Americans and black immigrants as separate and combative camps.1 Literature on the burgeoning multicultural and multiethnic populations of America suggest that African -

The Case for Funding Black-Led Social Change

The Case for Funding Black-Led Social Change Redlining by Another Name: What the Data Says to Move from Rhetoric to Action By: Emergent Pathways, LLC prepared for ABFE: A Philanthropic Partnership for Black Communities 1 The Case for Funding Black-Led Social Change Redlining by Another Name: What the Data Says to Move from Rhetoric to Action By: Emergent Pathways, LLC prepared for ABFE: A Philanthropic Partnership for Black Communities December 2019 ABFE A PHILANTHROPIC PARTNERSHIP FOR BLACK COMMUNITIES Introduction ABFE: A Philanthropic Partnership for Black • How much institutional philanthropic funding goes to Communities (ABFE), recently conducted a study to Black-led organizations in the United States (including learn how leaders of Black-led social change organizations in U.S. Territories)? • Given the higher concentrations of Black people in the the United States and U.S. Territories describe their interactions South and Midwest, how much institutional philan- with institutional philanthropy. The research had two purposes. thropic funding goes to Black-led organizations based The first was to build a body of information on the health and in these regions? well-being of existing Black social change infrastructure in this • How are institutional philanthropic funds that go to Black- country. The second was to use this information to inform the led organizations being used? future actions of the Black Social Change Funders Network • Who are some of the key organizations that make up the (BSCFN), as well as to encourage philanthropic staff, consul- existing infrastructure of Black-led social change groups, tants and trustees to change the ways they think and act with and what are the major needs that institutional philan- Black-led organizations (BLOs) and Black communities.