The American Naval Nightmare : Defending the Western Pacific, 1898-1922

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Military History Anniversaries 01 Thru 14 Feb

Military History Anniversaries 01 thru 14 Feb Events in History over the next 14 day period that had U.S. military involvement or impacted in some way on U.S military operations or American interests Feb 01 1781 – American Revolutionary War: Davidson College Namesake Killed at Cowan’s Ford » American Brigadier General William Lee Davidson dies in combat attempting to prevent General Charles Cornwallis’ army from crossing the Catawba River in Mecklenburg County, North Carolina. Davidson’s North Carolina militia, numbering between 600 and 800 men, set up camp on the far side of the river, hoping to thwart or at least slow Cornwallis’ crossing. The Patriots stayed back from the banks of the river in order to prevent Lieutenant Colonel Banastre Tartleton’s forces from fording the river at a different point and surprising the Patriots with a rear attack. At 1 a.m., Cornwallis began to move his troops toward the ford; by daybreak, they were crossing in a double-pronged formation–one prong for horses, the other for wagons. The noise of the rough crossing, during which the horses were forced to plunge in over their heads in the storm-swollen stream, woke the sleeping Patriot guard. The Patriots fired upon the Britons as they crossed and received heavy fire in return. Almost immediately upon his arrival at the river bank, General Davidson took a rifle ball to the heart and fell from his horse; his soaked corpse was found late that evening. Although Cornwallis’ troops took heavy casualties, the combat did little to slow their progress north toward Virginia. -

Colonial Contractions: the Making of the Modern Philippines, 1565–1946

Colonial Contractions: The Making of the Modern Philippines, 1565–1946 Colonial Contractions: The Making of the Modern Philippines, 1565–1946 Vicente L. Rafael Subject: Southeast Asia, Philippines, World/Global/Transnational Online Publication Date: Jun 2018 DOI: 10.1093/acrefore/9780190277727.013.268 Summary and Keywords The origins of the Philippine nation-state can be traced to the overlapping histories of three empires that swept onto its shores: the Spanish, the North American, and the Japanese. This history makes the Philippines a kind of imperial artifact. Like all nation- states, it is an ineluctable part of a global order governed by a set of shifting power rela tionships. Such shifts have included not just regime change but also social revolution. The modernity of the modern Philippines is precisely the effect of the contradictory dynamic of imperialism. The Spanish, the North American, and the Japanese colonial regimes, as well as their postcolonial heir, the Republic, have sought to establish power over social life, yet found themselves undermined and overcome by the new kinds of lives they had spawned. It is precisely this dialectical movement of empires that we find starkly illumi nated in the history of the Philippines. Keywords: Philippines, colonialism, empire, Spain, United States, Japan The origins of the modern Philippine nation-state can be traced to the overlapping histo ries of three empires: Spain, the United States, and Japan. This background makes the Philippines a kind of imperial artifact. Like all nation-states, it is an ineluctable part of a global order governed by a set of shifting power relationships. -

Afics BULLETIN New York

afics BULLETIN neW YorK ASSOCIATION OF FORMER INTERNATIONAL CIVIL SERVANTS Vol. 48 ♦ No. 2 ♦ Fall 2016 – Spring 2017 Photos by Mac Chiulli AFICS/NY members enjoy fine Cuban cuisine at Victor’s Café during annual winter luncheon, which also features presentation on the UN Food Garden. (See page 19.) “The mission of AFICS/NY is to support and promote the purposes, principles and programmes of the UN System; to advise and assist former international civil servants and those about to separate from service; to represent the interests of its members within the System; to foster social and personal relationships among members, to promote their well-being and to encourage mutual support of individual members." ASSOCIATION OF FORMER INTERNATIONAL CIVIL SERVANTS/NEW YorK HONORARY MEMBERS OthER BOARD MEMBERS Martti Ahtisaari J. Fernando Astete Kofi A. Annan Thomas Bieler Ban Ki-moon Gail Bindley-Taylor Aung San Suu Kyi Barbara Burns Javier Pérez de Cuéllar Mary Ann (Mac) Chiulli Ahsen Chowdury Frank Eppert GOVERNING BOARD Joan McDonald HONORARY MEMBERS Dr. Sudershan Narula Dr. Agnes Pasquier Andrés Castellanos del Corral Nancy Raphael O. Richard Nottidge Federico Riesco Edward Omotoso Warren Sach George F. Saddler Christine Smith-Lemarchand Linda Saputelli Gordon Tapper Jane Weidlund President of AFICS/NY Charities Foundation Anthony J. Fouracre OFFICERS President: John Dietz Office Staff Vice-Presidents: Deborah Landey, Jayantilal Karia Jamna Israni Velimir Kovacevic Secretary: Marianne Brzak-Metzler Deputy Secretary: Demetrios Argyriades Librarian Treasurer: Angel Silva Dawne Gautier CHANGE OF OFFICE STAFF In December 2016, we said goodbye to our part-time AFICS/ NY Office Staff member, Veronique Whalen, who has moved to Vienna, thanking her for her tremendous support to retirees and her special talent with everything to do with IT. -

2020 Philippines A&M V2.Indd

y th Year of Victor Victory in the Pacific M A Y 19 4 World War II in the Philippines 5 Bataan • Corregidor • Manila March 15-22, 2020 Featuring world-renowned expert on the war in the Pacific James M. Scott, author of Rampage: MacArthur, Yamashita and The Battle of Manila • In collaboration with The National WWII Museum • Save $1,000 per couple when booked by August 2, 2019 1946 Corregidor Muster. Photo by James T. Danklefs ‘43 Howdy, Ags! On December 7, 1941, the Imperial Japanese Navy attacked the US Pacific Fleet The Traveling Aggies are pleased to partner with The National WWII Museum on at Pearl Harbor. Just a few hours later, the Philippines faced the same fury Victory in the Pacific: World War II in the Philippines. This fascinating journey will as the Japanese Army Air Force began bombing Clark Field, located north of begin in the lush province of Bataan, where tour participants will walk the first Manila. Five months later, the Japanese forced the Americans in the Philippines kilometer of the Death March and visit the remains of the prisoner of war camp at to surrender, but not before General MacArthur could slip away to Australia, Cabanatuan. On the island of Corregidor, 27 miles out in Manila Bay, guests will famously vowing, “I shall return.” see the blasted, skeletal remains of the mile-long barracks, theater, hospital, and officers’ quarters, as well as the monument built and dedicated by The Association After the fall of the Philippines, 70,000 captured American and Filipino soldiers near Malinta Tunnel in 2015, flying the Texas A&M flag and representing the were sent on the infamous “Bataan Death March,” a 65-mile forced march into sacrifice, bravery and Aggie Spirit of the men who Mustered there. -

Proquest Dissertations

INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has been reproduced from the microfilm master. UMI films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from any type of computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to loe removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are reproduced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand comer and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. Each original is also photographed in one exposure and is included in reduced form at the back of the book. Photographs included in the original manuscript have been reproduced xerographically in this copy. Higher quality 6” x 9” black and white photographic prints are available for any photographs or illustrations appearing in this copy for an additional charge. Contact UMI directly to order. UMI* Bell & Howell Information and Learning 300 North Zeeb Road, Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 USA 800-521-0600 WASHINGTON IRVING CHAMBERS: INNOVATION, PROFESSIONALIZATION, AND THE NEW NAVY, 1872-1919 DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctorof Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Stephen Kenneth Stein, B.A., M.A. -

Joseph R. Mcmicking 1908 - 1990

JOSEPH R. MCMICKING 1908 - 1990 LEYTE LANDING OCTOBER, 20, 1944 THE BATTLE OF LEYTE GULF OCTOBER 23 TO 26, 1944 JOSEPH RALPH MCMICKING Joseph Ralph McMicking is known as a business maverick in three continents - his native Philippines, the United States and Spain. And yet, little is known about his service before and during World War II in the Pacific and even in the years following the war. A time filled with complete and utter service to the Philippine Commonwealth and the United States using his unique skills that would later on guide him in business. It was also a period of great personal sacrifice. He was born Jose Rafael McMicking in Manila on March 23, 1908, of Scottish-Spanish-Filipino descent. His father, lawyer Jose La Madrid McMick- ing, was the first Filipino Sheriff and Clerk of Court in American Manila, thereafter becoming the General Manager of the Insular Life Assurance Joe at 23 years old Company until his demise in early 1942. His mother was Angelina Ynchausti Rico from the Filipino business conglomerate of Ynchausti & Co. His early education started in Manila at the Catholic De la Salle School. He was sent to California for high school at the San Rafael Military Academy and went to Stanford University but chose to return to the Philippines before graduation. He married Mercedes Zobel in 1931 and became a General Manager of Ayala Cia, his wife’s Ynhausti, McMicking, Ortigas Family family business. He Joe is standing in the back row, 3rd from Right became a licensed pilot in 1932 and a part-time flight instructor with the newly-formed Philippine Army Air Corps in 1936. -

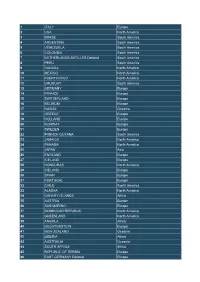

1 ITALY Europe 2 USA North America 3 BRASIL South America 4

1 ITALY Europe 2 USA North America 3 BRASIL South America 4 ARGENTINA South America 5 VENEZUELA South America 6 COLOMBIA South America 7 NETHERLANDS ANTILLES Deleted South America 8 PERU South America 9 CANADA North America 10 MEXICO North America 11 PUERTO RICO North America 12 URUGUAY South America 13 GERMANY Europe 14 FRANCE Europe 15 SWITZERLAND Europe 16 BELGIUM Europe 17 HAWAII Oceania 18 GREECE Europe 19 HOLLAND Europe 20 NORWAY Europe 21 SWEDEN Europe 22 FRENCH GUYANA South America 23 JAMAICA North America 24 PANAMA North America 25 JAPAN Asia 26 ENGLAND Europe 27 ICELAND Europe 28 HONDURAS North America 29 IRELAND Europe 30 SPAIN Europe 31 PORTUGAL Europe 32 CHILE South America 33 ALASKA North America 34 CANARY ISLANDS Africa 35 AUSTRIA Europe 36 SAN MARINO Europe 37 DOMINICAN REPUBLIC North America 38 GREENLAND North America 39 ANGOLA Africa 40 LIECHTENSTEIN Europe 41 NEW ZEALAND Oceania 42 LIBERIA Africa 43 AUSTRALIA Oceania 44 SOUTH AFRICA Africa 45 REPUBLIC OF SERBIA Europe 46 EAST GERMANY Deleted Europe 47 DENMARK Europe 48 SAUDI ARABIA Asia 49 BALEARIC ISLANDS Europe 50 RUSSIA Europe 51 ANDORA Europe 52 FAROER ISLANDS Europe 53 EL SALVADOR North America 54 LUXEMBOURG Europe 55 GIBRALTAR Europe 56 FINLAND Europe 57 INDIA Asia 58 EAST MALAYSIA Oceania 59 DODECANESE ISLANDS Europe 60 HONG KONG Asia 61 ECUADOR South America 62 GUAM ISLAND Oceania 63 ST HELENA ISLAND Africa 64 SENEGAL Africa 65 SIERRA LEONE Africa 66 MAURITANIA Africa 67 PARAGUAY South America 68 NORTHERN IRELAND Europe 69 COSTA RICA North America 70 AMERICAN -

Selected Bibliography of American History Through Biography

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 088 763 SO 007 145 AUTHOR Fustukjian, Samuel, Comp. TITLE Selected Bibliography of American History through Biography. PUB DATE Aug 71 NOTE 101p.; Represents holdings in the Penfold Library, State University of New York, College at Oswego EDRS PRICE MF-$0.75 HC-$5.40 DESCRIPTORS *American Culture; *American Studies; Architects; Bibliographies; *Biographies; Business; Education; Lawyers; Literature; Medicine; Military Personnel; Politics; Presidents; Religion; Scientists; Social Work; *United States History ABSTRACT The books included in this bibliography were written by or about notable Americans from the 16th century to the present and were selected from the moldings of the Penfield Library, State University of New York, Oswego, on the basis of the individual's contribution in his field. The division irto subject groups is borrowed from the biographical section of the "Encyclopedia of American History" with the addition of "Presidents" and includes fields in science, social science, arts and humanities, and public life. A person versatile in more than one field is categorized under the field which reflects his greatest achievement. Scientists who were more effective in the diffusion of knowledge than in original and creative work, appear in the tables as "Educators." Each bibliographic entry includes author, title, publisher, place and data of publication, and Library of Congress classification. An index of names and list of selected reference tools containing biographies concludes the bibliography. (JH) U S DEPARTMENT Of NIA1.114, EDUCATIONaWELFARE NATIONAL INSTITUTE OP EDUCATION THIS DOCUMENT HAS BEEN REPRO DUCED ExAC ICY AS RECEIVED FROM THE PERSON OR ORGANIZATIONORIGIN ATING IT POINTS OF VIEW OR OPINIONS STATED DO NOT NECESSARILYREPRE SENT OFFICIAL NATIONAL INSTITUTEOF EDUCATION POSITION OR POLICY PREFACE American History, through biograRhies is a bibliography of books written about 1, notable Americans, found in Penfield Library at S.U.N.Y. -

World War Ii in the Philippines

WORLD WAR II IN THE PHILIPPINES The Legacy of Two Nations©2016 Copyright 2016 by C. Gaerlan, Bataan Legacy Historical Society. All Rights Reserved. World War II in the Philippines The Legacy of Two Nations©2016 By Bataan Legacy Historical Society Several hours after the bombing of Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941, the Philippines, a colony of the United States from 1898 to 1946, was attacked by the Empire of Japan. During the next four years, thou- sands of Filipino and American soldiers died. The entire Philippine nation was ravaged and its capital Ma- nila, once called the Pearl of the Orient, became the second most devastated city during World War II after Warsaw, Poland. Approximately one million civilians perished. Despite so much sacrifice and devastation, on February 20, 1946, just five months after the war ended, the First Supplemental Surplus Appropriation Rescission Act was passed by U.S. Congress which deemed the service of the Filipino soldiers as inactive, making them ineligible for benefits under the G.I. Bill of Rights. To this day, these rights have not been fully -restored and a majority have died without seeing justice. But on July 14, 2016, this mostly forgotten part of U.S. history was brought back to life when the California State Board of Education approved the inclusion of World War II in the Philippines in the revised history curriculum framework for the state. This seminal part of WWII history is now included in the Grade 11 U.S. history (Chapter 16) curriculum framework. The approval is the culmination of many years of hard work from the Filipino community with the support of different organizations across the country. -

War Crimes in the Philippines During WWII Cecilia Gaerlan

War Crimes in the Philippines during WWII Cecilia Gaerlan When one talks about war crimes in the Pacific, the Rape of Nanking instantly comes to mind.Although Japan signed the 1929 Geneva Convention on the Treatment of Prisoners of War, it did not ratify it, partly due to the political turmoil going on in Japan during that time period.1 The massacre of prisoners-of-war and civilians took place all over countries occupied by the Imperial Japanese Army long before the outbreak of WWII using the same methodology of terror and bestiality. The war crimes during WWII in the Philippines described in this paper include those that occurred during the administration of General Masaharu Homma (December 22, 1941, to August 1942) and General Tomoyuki Yamashita (October 8, 1944, to September 3, 1945). Both commanders were executed in the Philippines in 1946. Origins of Methodology After the inauguration of the state of Manchukuo (Manchuria) on March 9, 1932, steps were made to counter the resistance by the Chinese Volunteer Armies that were active in areas around Mukden, Haisheng, and Yingkow.2 After fighting broke in Mukden on August 8, 1932, Imperial Japanese Army Vice Minister of War General Kumiaki Koiso (later convicted as a war criminal) was appointed Chief of Staff of the Kwantung Army (previously Chief of Military Affairs Bureau from January 8, 1930, to February 29, 1932).3 Shortly thereafter, General Koiso issued a directive on the treatment of Chinese troops as well as inhabitants of cities and towns in retaliation for actual or supposed aid rendered to Chinese troops.4 This directive came under the plan for the economic “Co-existence and co-prosperity” of Japan and Manchukuo.5 The two countries would form one economic bloc. -

Comparing the Basque Diaspora

COMPARING THE BASQUE DIASPORA: Ethnonationalism, transnationalism and identity maintenance in Argentina, Australia, Belgium, Peru, the United States of America, and Uruguay by Gloria Pilar Totoricagiiena Thesis submitted in partial requirement for Degree of Doctor of Philosophy The London School of Economics and Political Science University of London 2000 1 UMI Number: U145019 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Dissertation Publishing UMI U145019 Published by ProQuest LLC 2014. Copyright in the Dissertation held by the Author. Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code. ProQuest LLC 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 Theses, F 7877 7S/^S| Acknowledgments I would like to gratefully acknowledge the supervision of Professor Brendan O’Leary, whose expertise in ethnonationalism attracted me to the LSE and whose careful comments guided me through the writing of this thesis; advising by Dr. Erik Ringmar at the LSE, and my indebtedness to mentor, Professor Gregory A. Raymond, specialist in international relations and conflict resolution at Boise State University, and his nearly twenty years of inspiration and faith in my academic abilities. Fellowships from the American Association of University Women, Euskal Fundazioa, and Eusko Jaurlaritza contributed to the financial requirements of this international travel. -

1TT Ilitary ISTRICT 15 APRIL 1944 ENERAL HEADQU Rtilrs SQUI WES F2SPA LCEIC AREA Mitiaryi Intcligee Sectionl Ge:;;Neral Staff

. - .l AU 1TT ILiTARY ISTRICT 15 APRIL 1944 ENERAL HEADQU RTiLRS SQUI WES F2SPA LCEIC AREA Mitiaryi IntcligeE Sectionl Ge:;;neral Staff MINDA NAO AIR CENTERS 0) 5 0 10 20 30 SCALE IN MILS - ~PROVI~CIAL BOUNDARIEtS 1ST& 2ND CGLASS ROADIS h A--- TRAILS OPERATIONAL AIRDROMES O0 AIRDROMES UNDER CONSTRUCTION 0) SEAPLANE BASES (KNO N) _ _ _ _ 2 .__. ......... SITUATION OF FRIENDLY AR1'TED ORL'S IN TIDE PHILIPPINES 19 Luzon, Mindoro, Marinduque and i asbate: a) Iuzon: Pettit, Shafer free Luzon, Atwell & Ramsey have Hq near Antipolo, Rizal, Frank Johnson (Liguan Coal Mines), Rumsel (Altaco Transport, Rapu Rapu Id), Dick Wisner (Masbate Mines), all on Ticao Id.* b) IlocoseAbra: Number Americans free this area.* c) Bulacan: 28 Feb: 40 men Baliuag under Lt Pacif ico Cabreras. 8ev guerr loaders Bulacan, largest being under Lorenzo Villa, ox-PS, 1"x/2000 well armed men in "77th Regt".., BC co-op w/guerr thruout the prov.* d) Manila: 24 Mar: FREE PHILIPPITS has excellent coverage Manila, Bataan, Corregidor, Cavite, Batangas, Pampanga, Pangasinan, Tayabas, La Union, and larger sirbases & milit installations.* e) Tayabas: 19 Mar: Gen Gaudencia Veyra & guerr hit 3 towns on Bondoc Penin: Catanuan, Macal(lon & Genpuna && occu- pied them. Many BC reported killed,* f) icol Peninsula : 30 Mar: Oupt Zabat claims to have uni-s fied all 5th MD but Sorsogon.* g) Masbate: 2 Apr Recd : Villajada unit killed off by i.Maj Tanciongco for bribe by Japs.,* CODvjTNTS: (la) These men, but Ramsey, not previously reported. Ramsey previously reported in Nueva Ecija. (lb) Probably attached to guerrilla forces under Gov, Ablan.