Friends Who Host Benefits

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Trump Lawyer Seeks to Block Insider Book on White House

The Washington Post Politics Trump lawyer seeks to block insider book on White House By Josh Dawsey and Ashley Parker January 4 at 9:30 AM A lawyer representing President Trump sought Thursday to stop the publication of a new behind-the-scenes book about the White House that has already led Trump to angrily decry his former chief strategist Stephen K. Bannon. The legal notice — addressed to author Michael Wolff and the president of the book’s publisher — said Trump’s lawyers were pursuing possible charges including libel in connection with the forthcoming book, “Fire and Fury: Inside the Trump White House.” The letter by Beverly Hills-based attorney Charles J. Harder demanded the publisher, Henry Holt and Co., “immediately cease and desist from any further publication, release or dissemination of the book” or excerpts and summaries of its contents. The lawyers also seek a full copy of the book as part of their investigation. The latest twist in the showdown came after lawyers accused Bannon of breaching a confidentiality agreement and Trump denounced his former aide as a self-aggrandizing political charlatan who has “lost his mind.” It marked an abrupt and furious rupture with the onetime confidant that could have lasting political impact on the November midterms and beyond. The White House’s sharp public break with Bannon, which came in response to unflattering comments he made about Trump and his family in a new book about his presidency, left the self-fashioned populist alienated from his chief patron and even more isolated in his attempts to remake the Republican Party by backing insurgent candidates. -

In This Week's Issue

For Immediate Release: March 20, 2017 IN THIS WEEK’S ISSUE How Robert Mercer, a Reclusive Hedge-Fund Tycoon, Exploited America’s Populist Insurgency In the March 27, 2017, issue of The New Yorker, in “Trump’s Money Man” (p. 34), Jane Mayer profiles Robert Mercer, a reclusive Long Is- land billionaire and hedge-fund manager, and his daughter Rebekah, who exploited America’s populist insurgency to become a major force behind the Trump Presidency. Stephen Bannon, the President’s top strategist, told Mayer, “The Mercers laid the groundwork for the Trump revolution. Irrefutably, when you look at donors during the past four years, they have had the single biggest impact of anybody.” In the 2016 campaign, Mercer gave $22.5 million in disclosed donations to Republican candidates and to political-action committees. He also funded a rash of political projects and operatives. His influence was visible last month, in North Charleston, South Carolina, when Trump conferred privately with Patrick Caddell, a pollster who has worked for Mercer. Following their discussion, Trump issued a tweet calling the news media “the enemy of the American people.” Mayer writes, “The President is known for tweeting impulsively, but in this case his words weren’t spontaneous: they clearly echoed the thinking of Caddell, Bannon, and Mercer.” In 2012, Caddell had given a speech in which he called the media “the enemy of the American people.” That declaration was promoted by Breitbart News, a platform for the pro-Trump “alt-right,” of which Bannon was the executive chairman, before joining the Trump Administration. One of the main stake- holders in Breitbart News is Mercer. -

Eighteen Major New York Area Museums Participate in Instagram Swap

EIGHTEEN MAJOR NEW YORK AREA MUSEUMS PARTICIPATE IN INSTAGRAM SWAP THE FRICK COLLECTION PAIRS WITH NEW-YORK HISTORICAL SOCIETY In a first-of-its-kind collaboration, eighteen major New York City area institutions have joined forces to celebrate their unique collections and spaces on Instagram. All day today, February 2, the museums will post photos from this exciting project. Each participating museum paired with a sister institution, then set out to take photographs at that institution, capturing objects and moments that resonated with their own collections, exhibitions, and themes. As anticipated, each organization’s unique focus offers a new perspective on their partner museum. Throughout the day, the Frick will showcase its recent visit to the New-York Historical Society on its Instagram feed using the hashtag #MuseumInstaSwap. Posts will emphasize the connections between the two museums and libraries, both cultural landmarks in New York and both beloved for highlighting the city’s rich history. The public is encouraged to follow and interact to discover what each museum’s Instagram staffer discovered in the other’s space. A complete list of participating museums follows: American Museum of Natural History @AMNH The Museum of Modern Art @themuseumofmodernart Intrepid Sea, Air & Space Museum @intrepidmuseum Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum @cooperhewitt Museum of the City of New York @MuseumofCityNY New Museum @newmuseum 1 The Museum of Arts and Design @madmuseum Whitney Museum of American Art @whitneymuseum The Frick Collection -

Trump's Disinformation 'Magaphone'. Consequences, First Lessons and Outlook

BRIEFING Trump's disinformation 'magaphone' Consequences, first lessons and outlook SUMMARY The deadly insurrection at the US Capitol on 6 January 2021 was a significant cautionary example of the offline effects of online disinformation and conspiracy theories. The historic democratic crisis this has sparked − adding to a number of other historic crises the US is currently battling − provides valuable lessons not only for the United States, but also for Europe and the democratic world. The US presidential election and its aftermath saw domestic disinformation emerging as a more visible immediate threat than disinformation by third countries. While political violence has been the most tangible physical effect of manipulative information, corrosive conspiracy theories have moved from the fringes to the heart of political debate, normalising extremist rhetoric. At the same time, recent developments have confirmed that the lines between domestic and foreign attempts to undermine democracy are increasingly blurred. While the perceived weaknesses in democratic systems are − unsurprisingly − celebrated as a victory for authoritarian state actors, links between foreign interference and domestic terrorism are under growing scrutiny. The question of how to depolarise US society − one of a long list of challenges facing the Biden Administration − is tied to the polarised media environment. The crackdown by major social media platforms on Donald Trump and his supporters has prompted far-right groups to abandon the established information ecosystem to join right-wing social media. This could further accelerate the ongoing fragmentation of the US infosphere, cementing the trend towards separate realities. Ahead of the proposed Democracy Summit − a key objective of the Biden Administration − tempering the 'sword of democracy' has risen to the top of the agenda on both sides of the Atlantic. -

The Frick Collection

THE FRICK COLLECTION Building Upgrade and Expansion Fact Sheet Project Description: Honoring the architectural legacy and unique character of the Frick, the design for the upgrade and expansion by Selldorf Architects provides unprecedented access to the original 1914 home of Henry Clay Frick, preserves the intimate visitor experience and beloved galleries for which the Frick is known, and revitalizes the 70th Street Garden. Conceived to address pressing institutional and programmatic needs, the new plan creates new resources for permanent collection display and special exhibitions, conservation, and education and public programs, while upgrading visitor amenities and overall accessibility. The project marks the first comprehensive upgrade to the Frick’s buildings since the institution opened to the public eighty-two years ago in 1935. Groundbreaking: 2020 Location: 1 East 70th Street, New York, NY 10021 Square Footage: Current: 179,000 square feet Future: 197,000 square feet (10% increase) * *Note that this figure takes into consideration new construction as well as the loss of existing space resulting from the elimination of mezzanine levels in the library. Project Breakdown: Repurposed Space: 60,000 square feet New Construction: 27,000 square feet* **Given that 9,000 square feet of library stack space is removed through repurposing, the construction nets a total additional space of 18,000 square feet. Building Features & New Amenities: • 30% more gallery space for the collection and special exhibitions: o a series of approximately twelve -

Frick to Present First Exhibition in Thirty-Five Years Devoted to Highlights of Its Sèvres Porcelain Holdings

FRICK TO PRESENT FIRST EXHIBITION IN THIRTY-FIVE YEARS DEVOTED TO HIGHLIGHTS OF ITS SÈVRES PORCELAIN HOLDINGS FROM SÈVRES TO FIFTH AVENUE: FRENCH PORCELAIN AT THE FRICK COLLECTION April 28, 2015, through April 24, 2016 When Henry Clay Frick set out to furnish his new residence at 1 East 70th Street, his intention was to replicate the grand houses of the greatest European collectors, who surrounded their Old Master paintings with exquisite furniture and decorative objects. With the assistance of the art dealer Sir Joseph Duveen, Frick quickly assembled an impressive collection of decorative arts, including vases, potpourris, jugs, and basins made at Sèvres, the preeminent eighteenth-century Three Potpourri Vases, Sèvres Porcelain Manufactory, c. 1762, soft-paste porcelain, The Frick Collection; photo: Michael Bodycomb French porcelain manufactory. Many of these objects are featured in the upcoming exhibition From Sèvres to Fifth Avenue, which presents a new perspective on the collection by exploring the role Sèvres porcelain played in eighteenth-century France, as well as during the American Gilded Age. While some of these striking objects are regularly displayed in the grand context of the Fragonard and Boucher Rooms, others have come out of a long period of storage for this presentation. These finely painted examples will be seen together in a new light in the Portico Gallery. From Sèvres to Fifth Avenue is organized by Charlotte Vignon, Curator of Decorative Arts, The Frick Collection, and is made possible by Sidney R. Potpourri Vase “à Vaisseau,” Sèvres Porcelain Manufactory, Knafel and Londa Weisman. Through the year-long show, a number of c. -

Bachstitz, Inc. Records, 1923-1937

Bachstitz, Inc. records, 1923-1937 Finding aid prepared by Adrianna Slaughter, Karol Pick, and Aleksandr Gelfand This finding aid was generated using Archivists' Toolkit on September 18, 2013 The Metropolitan Museum of Art Archives 1000 Fifth Avenue New York, NY, 10028-0198 212-570-3937 [email protected] Bachstitz, Inc. records, 1923-1937 Table of Contents Summary Information .......................................................................................................3 Biographical Note................................................................................................................4 Scope and Contents note.....................................................................................................5 Arrangement note................................................................................................................ 6 Administrative Information .............................................................................................. 6 Controlled Access Headings............................................................................................... 7 Collection Inventory............................................................................................................8 Series I. Correspondence...............................................................................................8 Series II. General Administrative Records................................................................. 21 Series III. Inventory................................................................................................... -

December 2018

December 2018 Dear Neighbor, As we enter a season of giving and reflection, I want to share how wonderful it has been to serve you all over the past 12 months. We are coming into a time of year when we put aside differences in opinion to help those in need, give thanks, and celebrate all the good over the year. This year, I have introduced 27 bills focusing on housing, equal rights, criminal justice, and good government. My office has also served thousands of constituents on issues including housing, construction, quality of life, and more. I have a lot to celebrate as your Council Member, and I want to thank all of you for that. With the holiday season comes the arrival of many visitors to New York City, especially on Manhattan’s East Side and Midtown. While it is typical to complain about the overcrowding from tourists during the holiday, they have an undeniable impact on our city. Last month, I introduced legislation that would require the City to better track the economic benefits of tourism and allow New York to sustain and grow its multi-billion dollar industry. You can read more on the proposal in my op-ed in Crain’s. There is another constant of the season: snow. There are sure to be more storms like the one we experienced in November as winter approaches. While an anomaly for the fall, I heard from many of you regarding preparedness and issues stemming from downed trees. The City must be better prepared in response for future storms. -

Frick to Show Contemporary Digital Work in Conjunction with Old Masters from the Mauritshuis Rob and Nick Carter's Transformin

FRICK TO SHOW CONTEMPORARY DIGITAL WORK IN CONJUNCTION WITH OLD MASTERS FROM THE MAURITSHUIS ROB AND NICK CARTER’S TRANSFORMING STILL LIFE PAINTING October 22, 2013, through January 19, 2014 In a fairly unprecedented move for The Frick Collection―a museum known for its Old Masters―a contemporary digital work by British husband and wife team Rob and Nick Carter will be shown as a complement to Vermeer, Rembrandt, and Hals: Masterpieces of Dutch Painting from the Mauritshuis. By presenting this contemporary work alongside fifteen celebrated seventeenth-century Dutch paintings, the Frick offers an opportunity to consider the way in which Dutch Golden Age works continue to influence artists today. Indeed, the Carters’ work, Transforming Still Life Painting, a digitally rendered film, is their twenty-first-century rejoinder to the vanitas tradition. The work is directly inspired by Ambrosius Bosschaert the Elder’s (1573–1621) Vase of Flowers in a Window of about 1618 (a painting in the Mauritshuis’s collection but not included in the present exhibition). The famous still life features a vase of fastidiously described Still from Rob and Nick Carter, Transforming Still Life Painting, 2012, 3-hour looped film, frame and Apple Mac, Royal Picture Gallery Mauritshuis, The Hague, © Rob and Nick flowers displayed on a windowsill, behind which a bright sky and Carter picturesque seventeenth-century landscape are visible. The Carter s’ mesmerizing film literally transforms the genre by animating the nature morte. In the course of three hours, Bosschaert’s image changes gradually before our eyes: flowers whither, insects devour the tender foliage, and darkness descends on the distant mountains and river. -

Reciprocal Museum List

RECIPROCAL MUSEUM LIST DIA members at the Affiliate level and above receive reciprocal member benefits at more than 1,000 museums and cultural institutions in the U.S. and throughout North America, including free admission and member discounts. This list includes organizations affiliated with NARM (North American Reciprocal Museum) and ROAM (Reciprocal Organization of American Museums). Please note, some museums may restrict benefits. Please contact the institution for more information prior to your visit to avoid any confusion. UPDATED: 10/28/2020 DIA Reciprocal Museums updated 10/28/2020 State City Museum AK Anchorage Anchorage Museum at Rasmuson Center AK Haines Sheldon Museum and Cultural Center AK Homer Pratt Museum AK Kodiak Kodiak Historical Society & Baranov Museum AK Palmer Palmer Museum of History and Art AK Valdez Valdez Museum & Historical Archive AL Auburn Jule Collins Smith Museum of Fine Art AL Birmingham Abroms-Engel Institute for the Visual Arts (AEIVA), UAB AL Birmingham Birmingham Civil Rights Institute AL Birmingham Birmingham Museum of Art AL Birmingham Vulcan Park and Museum AL Decatur Carnegie Visual Arts Center AL Huntsville The Huntsville Museum of Art AL Mobile Alabama Contemporary Art Center AL Mobile Mobile Museum of Art AL Montgomery Montgomery Museum of Fine Arts AL Northport Kentuck Museum AL Talladega Jemison Carnegie Heritage Hall Museum and Arts Center AR Bentonville Crystal Bridges Museum of American Art AR El Dorado South Arkansas Arts Center AR Fort Smith Fort Smith Regional Art Museum AR Little Rock -

TIME Magazine, P.O

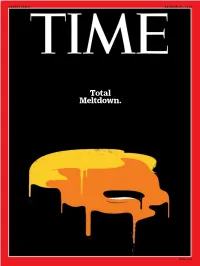

DOUBLE ISSUE OCTOBER 24, 2016 Total Meltdown. time.com THE YEAR’S BIGGEST BREAKOUT TV STAR Your favorite entertainment brands are now on TV New! Original programs, celebrity interviews and live events available FREE on-demand ALWAYS STREAMING on: Amazon Fire TV | Apple TV | Chromecast | Xfi nity | Roku Players | Xumo | mobile iOS and Android www.people.com/PEN Copyright © 2016 Time Inc. All rights reserved. VOL. 188, NO. 16–17 | 2016 Opioid epidemic: Fred Flati, a cop in East Liverpool, Ohio, shows a photo he took of a Sept. 7 overdose case that later went viral Photograph by Ben Lowy for TIME 2 | Conversation The View The Features Time Of 4 | For the Record Ideas, opinion, What to watch, read, The Brief innovations Uncivil War see and do News from the U.S. and 13 | Rana Foroohar The Republican nominee takes 85 | Christopher around the world on the culture that aim at his party Guest’s latest faux 5 | enables the 1% to By Alex Altman and Philip Elliott20 documentary, U.S.-Russia shield wealth from Mascots relations reach new fair taxation low 88 | Kevin Hart’s 14 | How table concert movie 6 | Meet the new The Issues manners serve up A voter’s guide to the domestic AmericanCardinals life lessons 89 | Ava DuVernay’s and foreign policy challenges that 7| 13th: a doc on the Violence escalates 15 | Glow-in-the- America’s next President must amendment that in Yemen Aug. 22, 2016 dark bike paths address. Featuring commentary abolished slavery 8 | from Barack Obama on closing Ian Bremmer on 15 | Tips for being 92 | YouTube’s what Brexit means more creative the wage gap; John Legend Miranda Sings for the E.U. -

© Copyright 2020 Yunkang Yang

© Copyright 2020 Yunkang Yang The Political Logic of the Radical Right Media Sphere in the United States Yunkang Yang A dissertation submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of Washington 2020 Reading Committee: W. Lance Bennett, Chair Matthew J. Powers Kirsten A. Foot Adrienne Russell Program Authorized to Offer Degree: Communication University of Washington Abstract The Political Logic of the Radical Right Media Sphere in the United States Yunkang Yang Chair of the Supervisory Committee: W. Lance Bennett Department of Communication Democracy in America is threatened by an increased level of false information circulating through online media networks. Previous research has found that radical right media such as Fox News and Breitbart are the principal incubators and distributors of online disinformation. In this dissertation, I draw attention to their political mobilizing logic and propose a new theoretical framework to analyze major radical right media in the U.S. Contrasted with the old partisan media literature that regarded radical right media as partisan news organizations, I argue that media outlets such as Fox News and Breitbart are better understood as hybrid network organizations. This means that many radical right media can function as partisan journalism producers, disinformation distributors, and in many cases political organizations at the same time. They not only provide partisan news reporting but also engage in a variety of political activities such as spreading disinformation, conducting opposition research, contacting voters, and campaigning and fundraising for politicians. In addition, many radical right media are also capable of forming emerging political organization networks that can mobilize resources, coordinate actions, and pursue tangible political goals at strategic moments in response to the changing political environment.