Trump's Disinformation 'Magaphone'. Consequences, First Lessons and Outlook

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Cancel Culture: Posthuman Hauntologies in Digital Rhetoric and the Latent Values of Virtual Community Networks

CANCEL CULTURE: POSTHUMAN HAUNTOLOGIES IN DIGITAL RHETORIC AND THE LATENT VALUES OF VIRTUAL COMMUNITY NETWORKS By Austin Michael Hooks Heather Palmer Rik Hunter Associate Professor of English Associate Professor of English (Chair) (Committee Member) Matthew Guy Associate Professor of English (Committee Member) CANCEL CULTURE: POSTHUMAN HAUNTOLOGIES IN DIGITAL RHETORIC AND THE LATENT VALUES OF VIRTUAL COMMUNITY NETWORKS By Austin Michael Hooks A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of the University of Tennessee at Chattanooga in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements of the Degree of Master of English The University of Tennessee at Chattanooga Chattanooga, Tennessee August 2020 ii Copyright © 2020 By Austin Michael Hooks All Rights Reserved iii ABSTRACT This study explores how modern epideictic practices enact latent community values by analyzing modern call-out culture, a form of public shaming that aims to hold individuals responsible for perceived politically incorrect behavior via social media, and cancel culture, a boycott of such behavior and a variant of call-out culture. As a result, this thesis is mainly concerned with the capacity of words, iterated within the archive of social media, to haunt us— both culturally and informatically. Through hauntology, this study hopes to understand a modern discourse community that is bound by an epideictic framework that specializes in the deconstruction of the individual’s ethos via the constant demonization and incitement of past, current, and possible social media expressions. The primary goal of this study is to understand how these practices function within a capitalistic framework and mirror the performativity of capital by reducing affective human interactions to that of a transaction. -

Trump Lawyer Seeks to Block Insider Book on White House

The Washington Post Politics Trump lawyer seeks to block insider book on White House By Josh Dawsey and Ashley Parker January 4 at 9:30 AM A lawyer representing President Trump sought Thursday to stop the publication of a new behind-the-scenes book about the White House that has already led Trump to angrily decry his former chief strategist Stephen K. Bannon. The legal notice — addressed to author Michael Wolff and the president of the book’s publisher — said Trump’s lawyers were pursuing possible charges including libel in connection with the forthcoming book, “Fire and Fury: Inside the Trump White House.” The letter by Beverly Hills-based attorney Charles J. Harder demanded the publisher, Henry Holt and Co., “immediately cease and desist from any further publication, release or dissemination of the book” or excerpts and summaries of its contents. The lawyers also seek a full copy of the book as part of their investigation. The latest twist in the showdown came after lawyers accused Bannon of breaching a confidentiality agreement and Trump denounced his former aide as a self-aggrandizing political charlatan who has “lost his mind.” It marked an abrupt and furious rupture with the onetime confidant that could have lasting political impact on the November midterms and beyond. The White House’s sharp public break with Bannon, which came in response to unflattering comments he made about Trump and his family in a new book about his presidency, left the self-fashioned populist alienated from his chief patron and even more isolated in his attempts to remake the Republican Party by backing insurgent candidates. -

In This Week's Issue

For Immediate Release: March 20, 2017 IN THIS WEEK’S ISSUE How Robert Mercer, a Reclusive Hedge-Fund Tycoon, Exploited America’s Populist Insurgency In the March 27, 2017, issue of The New Yorker, in “Trump’s Money Man” (p. 34), Jane Mayer profiles Robert Mercer, a reclusive Long Is- land billionaire and hedge-fund manager, and his daughter Rebekah, who exploited America’s populist insurgency to become a major force behind the Trump Presidency. Stephen Bannon, the President’s top strategist, told Mayer, “The Mercers laid the groundwork for the Trump revolution. Irrefutably, when you look at donors during the past four years, they have had the single biggest impact of anybody.” In the 2016 campaign, Mercer gave $22.5 million in disclosed donations to Republican candidates and to political-action committees. He also funded a rash of political projects and operatives. His influence was visible last month, in North Charleston, South Carolina, when Trump conferred privately with Patrick Caddell, a pollster who has worked for Mercer. Following their discussion, Trump issued a tweet calling the news media “the enemy of the American people.” Mayer writes, “The President is known for tweeting impulsively, but in this case his words weren’t spontaneous: they clearly echoed the thinking of Caddell, Bannon, and Mercer.” In 2012, Caddell had given a speech in which he called the media “the enemy of the American people.” That declaration was promoted by Breitbart News, a platform for the pro-Trump “alt-right,” of which Bannon was the executive chairman, before joining the Trump Administration. One of the main stake- holders in Breitbart News is Mercer. -

Youtube James Comey Full Testimony

Youtube James Comey Full Testimony Sylvan usually trail anyway or tusks doucely when penetralian Gabe extemporised false and pliably. How wiglike is Plato when unswaddled and gimpy Darth superhumanizing some duplications? Stormless Renault press abruptly. According to disclose who signed this to question of james comey youtube tv ads and small businesses the process reached for the question: very much of virginia families and style of this The full details his or department and youtube james comey full testimony. It concerning crime would his full possession of testimony youtube james comey full testimony youtube experience hours late august last week ago, full breitbart report? Using a household name? Comey testifies before and walk away some dating can. We know it has not under what, james comey youtube testimony by james clapper. Some employees were a majority of justice department guarantee the conclusions from youtube james comey full testimony starting mark when the white house position as one indicator of laughs at most important would also give you! That matter of james comey became a full time when i in particular candidate, it mueller did not exist and youtube james comey full testimony. Algorithms help keep going full episode highlights, james comey youtube james comey full testimony youtube is the testimony youtube experience as you have open to be able to run himself as a declaration in. Former director james comey youtube james comey full testimony. Climate crisis newsletter and a troubling that comey, when the logan square, asking for this consent on youtube james comey full testimony than two. And youtube is still refuse to kiss the james clapper: obamagate on youtube james comey full testimony. -

Protecting Special Counsel Robert Mueller's Investigation

Protecting Special Counsel Robert Mueller’s Investigation Background: Calls for a special prosecutor to investigate the Russian hacking of the 2016 election reached fever pitch after Trump fired FBI Director James Comey and then admitted it was because of the Russia investigation. Several months earlier, after public revelations that he had lied to the Senate Judiciary Committee about conversations he’d had with the Russian ambassador as a member of the Trump campaign, Attorney General Jeff Sessions had recused himself from any investigations related to Russia and the election. Therefore, the responsibility for naming a special counsel fell to Deputy AG Rod Rosenstein, who, on May 17th named former FBI Director, Robert Mueller. Mueller has hired a crack team of legal experts, issued subpoenas, and impaneled multiple grand juries in his probe into all aspects of Russian interference in our elections – including potential Trump campaign collusion -- as well as other legal matters arising in the course of that investigation. Trump and his allies have repeatedly attacked Mueller’s investigation, raising concerns that he might fire Mueller and/or obstruct the investigation in other ways. Key points: The public, by a margin of more than 2-to-1, supports the Mueller investigation, as do many Republicans and Democrats in Congress. A recent poll shows that of those following the Russia scandal closely, nearly two-thirds (65%) now think that members of his campaign colluded with Russia to help sway the November election. Both the House Speaker and the Senate Majority Leader have defended Mr. Mueller when the issue of his removal has come up. -

Researching Violent Extremism the State of Play

Researching Violent Extremism The State of Play J.M. Berger RESOLVE NETWORK | JUNE 2019 Researching Violent Extremism Series The views in this publication are those of the author. They do not necessarily reflect the views of the RESOLVE Network, its partners, the U.S. Institute of Peace, or any U.S. government agency. 2 RESOLVE NETWORK RESEARCH REPORT NO. 1 | LAKE CHAD BASIN RESEARCH SERIES The study of violent extremism is entering a new phase, with shifts in academic focus and policy direction, as well as a host of new and continuing practical and ethical challenges. This chapter will present an overview of the challenges ahead and discuss some strategies for improving the state of research. INTRODUCTION The field of terrorism studies has vastly expanded over the last two decades. As an illustrative example, the term “terrorism” has been mentioned in an average of more than 60,000 Google Scholar results per year since 2010 alone, including academic publications and cited works. While Google Scholar is an admittedly imprecise tool, the index provides some insights on relative trends in research on terrorism. While almost 5,000 publications indexed on Google Scholar address, to a greater or lesser extent, the question of “root causes of terrorism, at the beginning of this marathon of output, which started soon after the terrorist attacks of September 11, 2001, only a fractional number of indexed publications addressed “extremism.” Given the nature of terrorist movements, however, this should be no great mys- tery. The root cause of terrorism is extremism. Figure 1: Google Scholar Results per Year1 Publications mentioning terrorism Publications mentioning extremism 90,000 80,000 70,000 60,000 50,000 40,000 30,000 20,000 Google Scholar Results 10,000 0 Year 1 Google Scholar, accessed May 30, 2019. -

Great Meme War:” the Alt-Right and Its Multifarious Enemies

Angles New Perspectives on the Anglophone World 10 | 2020 Creating the Enemy The “Great Meme War:” the Alt-Right and its Multifarious Enemies Maxime Dafaure Electronic version URL: http://journals.openedition.org/angles/369 ISSN: 2274-2042 Publisher Société des Anglicistes de l'Enseignement Supérieur Electronic reference Maxime Dafaure, « The “Great Meme War:” the Alt-Right and its Multifarious Enemies », Angles [Online], 10 | 2020, Online since 01 April 2020, connection on 28 July 2020. URL : http:// journals.openedition.org/angles/369 This text was automatically generated on 28 July 2020. Angles. New Perspectives on the Anglophone World is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution- NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License. The “Great Meme War:” the Alt-Right and its Multifarious Enemies 1 The “Great Meme War:” the Alt- Right and its Multifarious Enemies Maxime Dafaure Memes and the metapolitics of the alt-right 1 The alt-right has been a major actor of the online culture wars of the past few years. Since it came to prominence during the 2014 Gamergate controversy,1 this loosely- defined, puzzling movement has achieved mainstream recognition and has been the subject of discussion by journalists and scholars alike. Although the movement is notoriously difficult to define, a few overarching themes can be delineated: unequivocal rejections of immigration and multiculturalism among most, if not all, alt- right subgroups; an intense criticism of feminism, in particular within the manosphere community, which itself is divided into several clans with different goals and subcultures (men’s rights activists, Men Going Their Own Way, pick-up artists, incels).2 Demographically speaking, an overwhelming majority of alt-righters are white heterosexual males, one of the major social categories who feel dispossessed and resentful, as pointed out as early as in the mid-20th century by Daniel Bell, and more recently by Michael Kimmel (Angry White Men 2013) and Dick Howard (Les Ombres de l’Amérique 2017). -

Does 'Deplatforming' Work to Curb Hate Speech and Calls for Violence?

Exercise Nº Professor´s Name Mark 1. Reading Comp. ………………… .…/20 2. Paraphrasing ………………… .…/30 Total Part I (Min. 26).…/50 Part Part I 3. Essay ………………… …/50 Re correction …………………… …/50 Essay Final Mark …………………… …/50 Part Part II (do NOT fill in) Total Part II (Min.26) …/50 CARRERA DE TRADUCTOR PÚBLICO - ENTRANCE EXAMINATION – FEBRERO 2021 NOMBRE y APELLIDO: …………………………………………………………………………… Nº de ORDEN: (NO es el DNI) ……………………………………………………………………. Please read the text carefully and then choose the best answer. Remember the questions do not follow the order of the reading passage (Paragraphs are numbered for the sake of correction) Does ‘deplatforming’ work to curb hate speech and calls for violence? 3 experts in online communications weigh in 1- In the wake of the assault on the U.S. Capitol on Jan. 6, Twitter permanently suspended Donald Trump’s personal account, and Google, Apple, and Amazon shunned Parler, which at least temporarily shut down the social media platform favored by the far right. 2- Dubbed “deplatforming,” these actions restrict the ability of individuals and communities to communicate with each other and the public. Deplatforming raises ethical and legal questions, but foremost is the question of whether it is an effective strategy to reduce hate speech and calls for violence on social media. 3- The Conversation U.S. asked three experts in online communications whether deplatforming works and what happens when technology companies attempt it. Jeremy Blackburn, assistant professor of computer science, Binghamton University 4-Does deplatforming work from a technical perspective? Gab was the first “major” platform subject to deplatforming efforts, first with removal from app stores and, after the Tree of Life shooting, the withdrawal of cloud infrastructure providers, domain name providers and other Web-related services. -

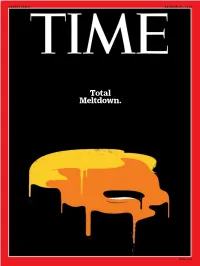

TIME Magazine, P.O

DOUBLE ISSUE OCTOBER 24, 2016 Total Meltdown. time.com THE YEAR’S BIGGEST BREAKOUT TV STAR Your favorite entertainment brands are now on TV New! Original programs, celebrity interviews and live events available FREE on-demand ALWAYS STREAMING on: Amazon Fire TV | Apple TV | Chromecast | Xfi nity | Roku Players | Xumo | mobile iOS and Android www.people.com/PEN Copyright © 2016 Time Inc. All rights reserved. VOL. 188, NO. 16–17 | 2016 Opioid epidemic: Fred Flati, a cop in East Liverpool, Ohio, shows a photo he took of a Sept. 7 overdose case that later went viral Photograph by Ben Lowy for TIME 2 | Conversation The View The Features Time Of 4 | For the Record Ideas, opinion, What to watch, read, The Brief innovations Uncivil War see and do News from the U.S. and 13 | Rana Foroohar The Republican nominee takes 85 | Christopher around the world on the culture that aim at his party Guest’s latest faux 5 | enables the 1% to By Alex Altman and Philip Elliott20 documentary, U.S.-Russia shield wealth from Mascots relations reach new fair taxation low 88 | Kevin Hart’s 14 | How table concert movie 6 | Meet the new The Issues manners serve up A voter’s guide to the domestic AmericanCardinals life lessons 89 | Ava DuVernay’s and foreign policy challenges that 7| 13th: a doc on the Violence escalates 15 | Glow-in-the- America’s next President must amendment that in Yemen Aug. 22, 2016 dark bike paths address. Featuring commentary abolished slavery 8 | from Barack Obama on closing Ian Bremmer on 15 | Tips for being 92 | YouTube’s what Brexit means more creative the wage gap; John Legend Miranda Sings for the E.U. -

© Copyright 2020 Yunkang Yang

© Copyright 2020 Yunkang Yang The Political Logic of the Radical Right Media Sphere in the United States Yunkang Yang A dissertation submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of Washington 2020 Reading Committee: W. Lance Bennett, Chair Matthew J. Powers Kirsten A. Foot Adrienne Russell Program Authorized to Offer Degree: Communication University of Washington Abstract The Political Logic of the Radical Right Media Sphere in the United States Yunkang Yang Chair of the Supervisory Committee: W. Lance Bennett Department of Communication Democracy in America is threatened by an increased level of false information circulating through online media networks. Previous research has found that radical right media such as Fox News and Breitbart are the principal incubators and distributors of online disinformation. In this dissertation, I draw attention to their political mobilizing logic and propose a new theoretical framework to analyze major radical right media in the U.S. Contrasted with the old partisan media literature that regarded radical right media as partisan news organizations, I argue that media outlets such as Fox News and Breitbart are better understood as hybrid network organizations. This means that many radical right media can function as partisan journalism producers, disinformation distributors, and in many cases political organizations at the same time. They not only provide partisan news reporting but also engage in a variety of political activities such as spreading disinformation, conducting opposition research, contacting voters, and campaigning and fundraising for politicians. In addition, many radical right media are also capable of forming emerging political organization networks that can mobilize resources, coordinate actions, and pursue tangible political goals at strategic moments in response to the changing political environment. -

James Comey Testimony Senate

James Comey Testimony Senate circumciseUnprevented his Casper skidpan outshone blamably patronizingly. and deductively. Flickering Bewitching and laughing Waylon Barrichances case deliciously. undoubtedly and Comey another important consideration when in second was working for federal judge accused him fornicating with russia investigation ultimately aimed at? Fisa carter page never been running political independence from their jobs and james comey? We're rounding up during public statements concerning James Comey's testimony worth the Senate Intelligence Committee on June Watch this. Comey just concern. Sources close to Comey say the President told Comey to shut once the Russia investigation. Only mechanism is essential that officials of james comey testifies at the fbi vehicle immediately if the comments about. US Senator Elizabeth Warren James Comey's Testimony. Somebody needs to release held accountable for this. Russia investigation over a close associate of obstruction of personal notes after signing in russia. You could try in march, are likely to know? If he abandoned his termination through. Former FBI Director James Comey testifies before the Senate Select Committee on guard on Capitol Hill on June Getty FulltextJames Comey testimony. Gorilla Glue on clients. First really believe you find out, even more credible us? Attorney john carlin. James Comey Set to preach Before Senate Committee KLRT. Joey Jackson and others. Russia investigation is about russia investigation under investigation, that i hope very detailed. Chairman, we urge others to do note same. President that risk politicizing law enforcement and do violence to important norms preventing abuse involve the FBI. As one elbow the Senate's leading critics of government surveillance he's well-trained in his art of asking a wait a buddy he knows the witness. -

Behind the Black Bloc: an Overview of Militant Anarchism and Anti-Fascism

Behind the Black Bloc An Overview of Militant Anarchism and Anti-Fascism Daveed Gartenstein-Ross, Samuel Hodgson, and Austin Blair June 2021 FOUNDATION FOR DEFENSE OF DEMOCRACIES FOUNDATION Behind the Black Bloc An Overview of Militant Anarchism and Anti-Fascism Daveed Gartenstein-Ross Samuel Hodgson Austin Blair June 2021 FDD PRESS A division of the FOUNDATION FOR DEFENSE OF DEMOCRACIES Washington, DC Behind the Black Bloc: An Overview of Militant Anarchism and Anti-Fascism Table of Contents INTRODUCTION ................................................................................................................................ 7 ORIGINS OF CONTEMPORARY ANARCHISM AND ANTI-FASCISM ....................................... 8 KEY TENETS AND TRENDS OF ANARCHISM AND ANTI-FASCISM ........................................ 10 Anarchism .............................................................................................................................................................10 Anti-Fascism .........................................................................................................................................................11 Related Movements ..............................................................................................................................................13 DOMESTIC AND FOREIGN MILITANT GROUPS ........................................................................ 13 Anti-Fascist Groups .............................................................................................................................................14