New Directions In

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Global Proxy Voting Records

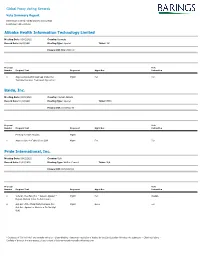

Global Proxy Voting Records Vote Summary Report Date range covered: 03/01/2021 to 03/31/2021 Location(s): All Locations Alibaba Health Information Technology Limited Meeting Date: 03/01/2021 Country: Bermuda Record Date: 02/23/2021 Meeting Type: Special Ticker: 241 Primary ISIN: BMG0171K1018 Proposal Vote Number Proposal Text Proponent Mgmt Rec Instruction 1 Approve Revised Annual Cap Under the Mgmt For For Technical Services Framework Agreement Baidu, Inc. Meeting Date: 03/01/2021 Country: Cayman Islands Record Date: 01/28/2021 Meeting Type: Special Ticker: BIDU Primary ISIN: US0567521085 Proposal Vote Number Proposal Text Proponent Mgmt Rec Instruction Meeting for ADR Holders Mgmt 1 Approve One-to-Eighty Stock Split Mgmt For For Pride International, Inc. Meeting Date: 03/01/2021 Country: USA Record Date: 12/01/2020 Meeting Type: Written Consent Ticker: N/A Primary ISIN: US74153QAJ13 Proposal Vote Number Proposal Text Proponent Mgmt Rec Instruction 1 Vote On The Plan (For = Accept, Against = Mgmt For Abstain Reject; Abstain Votes Do Not Count) 2 Opt Out of the Third-Party Releases (For = Mgmt None For Opt Out, Against or Abstain = Do Not Opt Out) * Instances of "Do Not Vote" are normally owing to: - Share-blocking - temporary restriction of trading by the Sub-Custodian following vote submission - Client restrictions - Conflicts of Interest. For any queries, please contact [email protected] Global Proxy Voting Records Vote Summary Report Date range covered: 03/01/2021 to 03/31/2021 Location(s): All Locations The -

Harga Sewaktu Wak Jadi Sebelum

HARGA SEWAKTU WAKTU BISA BERUBAH, HARGA TERBARU DAN STOCK JADI SEBELUM ORDER SILAHKAN HUBUNGI KONTAK UNTUK CEK HARGA YANG TERTERA SUDAH FULL ISI !!!! Berikut harga HDD per tgl 14 - 02 - 2016 : PROMO BERLAKU SELAMA PERSEDIAAN MASIH ADA!!! EXTERNAL NEW MODEL my passport ultra 1tb Rp 1,040,000 NEW MODEL my passport ultra 2tb Rp 1,560,000 NEW MODEL my passport ultra 3tb Rp 2,500,000 NEW wd element 500gb Rp 735,000 1tb Rp 990,000 2tb WD my book Premium Storage 2tb Rp 1,650,000 (external 3,5") 3tb Rp 2,070,000 pakai adaptor 4tb Rp 2,700,000 6tb Rp 4,200,000 WD ELEMENT DESKTOP (NEW MODEL) 2tb 3tb Rp 1,950,000 Seagate falcon desktop (pake adaptor) 2tb Rp 1,500,000 NEW MODEL!! 3tb Rp - 4tb Rp - Hitachi touro Desk PRO 4tb seagate falcon 500gb Rp 715,000 1tb Rp 980,000 2tb Rp 1,510,000 Seagate SLIM 500gb Rp 750,000 1tb Rp 1,000,000 2tb Rp 1,550,000 1tb seagate wireless up 2tb Hitachi touro 500gb Rp 740,000 1tb Rp 930,000 Hitachi touro S 7200rpm 500gb Rp 810,000 1tb Rp 1,050,000 Transcend 500gb Anti shock 25H3 1tb Rp 1,040,000 2tb Rp 1,725,000 ADATA HD 710 750gb antishock & Waterproof 1tb Rp 1,000,000 2tb INTERNAL WD Blue 500gb Rp 710,000 1tb Rp 840,000 green 2tb Rp 1,270,000 3tb Rp 1,715,000 4tb Rp 2,400,000 5tb Rp 2,960,000 6tb Rp 3,840,000 black 500gb Rp 1,025,000 1tb Rp 1,285,000 2tb Rp 2,055,000 3tb Rp 2,680,000 4tb Rp 3,460,000 SEAGATE Internal 500gb Rp 685,000 1tb Rp 835,000 2tb Rp 1,215,000 3tb Rp 1,655,000 4tb Rp 2,370,000 Hitachi internal 500gb 1tb Toshiba internal 500gb Rp 630,000 1tb 2tb Rp 1,155,000 3tb Rp 1,585,000 untuk yang ingin -

The US in South Korea

THE U.S. IN SOUTH KOREA: ALLY OR EMPIRE? PERSPECTIVES IN GEOPOLITICS GRADE: 9-12 AUTHOR: Sharlyn Scott TOPIC/THEME: Social Studies TIME REQUIRED: Four to five 55-minute class periods BACKGROUND: This lesson examines different perspectives on the relationship between the U.S. and the Republic of Korea (R.O.K. – South Korea) historically and today. Is the United States military presence a benevolent force protecting both South Korean and American interests in East Asia? Or is the U.S. a domineering empire using the hard power of its military in South Korea solely to achieve its own geopolitical goals in the region and the world? Are there issues between the ROK and the U.S. that can be resolved for mutually beneficial results? An overview of the history of U.S. involvement in Korea since the end of World War II will be studied for context in examining these questions. In addition, current academic and newspaper articles as well as op-ed pieces by controversial yet reliable sources will offer insight into both American and South Korean perspectives. These perspectives will be analyzed as students grapple with important geopolitical questions involving the relationship between the U.S. and the R.O.K. CURRICULUM CONNECTION: This unit could be used with regional Geography class, World History, as well as American History as it relates to the Korean War and/or U.S. military expansion OBJECTIVES AND STANDARDS: The student will be able to: 1. Comprehend the historical relationship of the U.S. and the Korean Peninsula 2. Demonstrate both the U.S. -

BTS) Official Twitter

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by UKM Journal Article Repository 3L: The Southeast Asian Journal of English Language Studies – Vol 23(3): 67 – 80 http://doi.org/10.17576/3L-2017-2303-05 Korean-English Language Translational Action of K-Pop Social Media Content: A Case Study on Bangtan Sonyeondan’s (BTS) Official Twitter AZNUR AISYAH Foreign Language and Translation Unit Universiti Kebangsaan Malaysia Malay Language Department Tokyo University of Foreign Language Studies (Visiting Lecturer) [email protected] ABSTRACT K-pop fans face language barriers on a daily basis when searching for their favourite K-Pop group related news. The translators’ role in mediating information between the international fans with the K-Pop artists is central in delivering the necessary information to its fans around the globe. This study has been motivated by the scarcity of research on the progress of translation in social media microblogging such as Twitter. It was aimed at analysing translation progress occurring in social media, namely the Twitter account, where communication discourse activities actively occurred. Big Hit Entertainment’s Twitter account (@BigHitEnt) was selected as the primary data sample because of the outstanding reputation of Bangtan Sonyeondan (BTS), a K-Pop idol group under the company’s label, in terms of social media engagement. This research employed the Social Media Translational Action (SoMTA) analytical framework, a new research methodology adapted from the Translational Action framework, for its data analysis. The content of the news feed in Twitter’s timeline is mostly written in the Korean language which might not be understood by the international fans who do not speak Korean. -

Development Cooperation with North Korea: Expanding the Debate Beyond the Political Horizon

Development Cooperation with North Korea: Expanding the Debate Beyond the Political Horizon By Benjamin Katzeff Silberstein Issues & Insights Vol.16-No. 1 Honolulu, Hawaii January 2016 Pacific Forum CSIS Based in Honolulu, the Pacific Forum CSIS (www.pacforum.org) operates as the autonomous Asia-Pacific arm of the Center for Strategic and International Studies in Washington, DC. The Forum’s programs encompass current and emerging political, security, economic, business, and oceans policy issues through analysis and dialogue undertaken with the region’s leaders in the academic, government, and corporate areas. Founded in 1975, it collaborates with a broad network of research institutes from around the Pacific Rim, drawing on Asian perspectives and disseminating project findings and recommendations to opinion leaders, governments, and members of the public throughout the region. Table of Contents Page Acknowledgements ………………………………………………………………………… iv Executive Summary ………………………………………………………………………… v Introduction ….………………………………………………………………………………. 1 Approach and methodology …………………………………………………………………. 2 Development cooperation with North Korea: an overview ….……….……………………… 3 Eight ideas for development cooperation with North Korea ………………………………… 5 Food security and the markets …………………………………………………………… 5 The financial system ………………….…………………………………………………. 8 Trade and foreign investment ……………………………………………………………. 12 Governance ………………………………………………………………………………. 14 Conclusion …………………………………………………………………………………… 17 References …………………………………………………………………………………… -

David Hawk, the Hidden Gulag IV

H R Committee for Human Rights in North Korea N K The Hidden Gulag IV GENDER REPRESSION & PRISONER DISAPPEARANCES DAVID HAWK Satellite image of the new women’s section in Jongo-ri Prison The Hidden Gulag IV GENDER REPRESSION & PRISONER DISAPPEARANCES DAVID HAWK Copyright © 2015 by the Committee for Human Rights in North Korea All rights reserved Printed in the United States of America ISBN: 9780985648046 Library of Congress Control Number: 2015947712 The Hidden Gulag IV GENDER REPRESSION & PRISONER DISAPPEARANCES Committee for Human Rights in North Korea 1001 Connecticut Avenue, NW, Suite 435 Washington, DC 20036 www.hrnk.org I ABOUT THE COMMITTEE FOR HUMAN RIGHTS IN NORTH KOREA (HRNK) HRNK is the leading U.S.-based bipartisan, non-governmental organization in the field of North Korean human rights research and advocacy, tasked to focus international attention on human rights abuses in that country. It is HRNK’s mission to persistently remind policy makers, opinion leaders, and the general public in the free world and beyond that more than 20 million North Koreans need our attention. Since its establishment in 2001, HRNK has played an important intellectual leadership role on North Korean human rights issues by publishing twenty-one major reports (available at http://hrnk.org/publications/ hrnk-publications.php). HRNK became the first organization to propose that the human rights situation in North Korea be addressed by the UN Security Council. HRNK was directly, actively, and effectively involved in all stages of the process supporting the work of the UN Commission of Inquiry. On many occasions, HRNK has been invited to provide expert testimony before the U.S. -

META'17 Incheon

META’17 Incheon - Korea The 8th International Conference on Metamaterials, Photonic Crystals and Plasmonics Program July 25 – 28, 2017 Incheon, Korea metaconferences.org .metaconferences.org META’17 Incheon - Korea The 8th International Conference on Metamaterials, Photonic Crystals and Plasmonics Please share your comments, photos & videos ! www.facebook.com/metaconference @metaconference Edited by Said Zouhdi | Paris-Sud University, France Junsuk Rho | POSTECH, Korea Hakjoo Lee | CAMM, Korea CONTENTS META’17 ORGANIZATION ........................................ 5 PLENARY SPEAKERS ........................................... 7 KEYNOTE SPEAKERS ........................................... 12 META’17 VENUE ............................................... 14 GUIDELINES FOR PRESENTERS ................................... 17 PRE-CONFERENCE TUTORIALS ................................... 18 TECHNICAL PROGRAM .......................................... 30 META’17 ORGANIZATION Said Zouhdi, General Chair Junsuk Rho, General Co-Chair Hakjoo Lee, General Co-Chair Paris–Sud University, France POSTECH, Korea CAMM, Korea INTERNATIONAL ADVISORY COMMITTEE Harry Atwater, USA Graeme W. Milton, USA Ari Sihvola, Finland Federico Capasso, USA Raj Mittra, USA David R. Smith, USA Andre de Lustrac, France Manuel Nieto-Vesperinas, Spain J(Yiannis) Vardaxoglou, UK Nader Engheta, USA Susumu Noda, Japan Martin Wegener, Germany Teruya Ishihara, Japan Masaya Notomi, Japan Xiang Zhang, USA Tatsuo Itoh, USA Yahya Rahmat-Samii, USA Nikolay Zheludev, UK Yuri Kivshar, Australia -

Istomin Hailed for Overrule Honesty

NOVEMBER 22, 20 CHINA DAILY PAGE 7 OFF TRACK Korea sets sights WHO’S SAYING WHAT... on 75 gold medals Istomin “Smoking helps me feel better, forcing me to forget about the Inspired by its team’s excellent hailed for performances through the fi rst results. My teammate smokes half of the competition, Korea overrule as well.” is targeting 75 gold medals at the Equestrian rider SONG SANG-WUK Asian Games. honesty of Korea, on how he relaxes at an event “Our athletes have been per- forming well until now. Our gen- “Th at will be my winter project.” eral goal is 75 gold medals,” said India’s Karan Rastogi Lee Kee-heung, chef-de-mission (below) hailed Denis Germany-based Japanese equestrian medalist YOSHIAKI OIWA, on his Istomin (right) as an of the Korean delegation. plans for the off -season Korea has enjoyed its best per- “incredible champion” formances in shooting (13 gold after the Uzbek top “He deserves it. He said some- medals), judo (6) and swimming seed overruled a line (4). It also has the potential to call on match point in thing insulting to the referee.” scale new heights in fencing and their Asian Games men’s Saudi Arabia’s water polo assistant cycling, sports in which it has coach MOHAMMED GHALLAB, on won fi ve and three gold medals tennis quarterfi nal on Adel Al Malki’s ejection so far, respectively. Sunday. “Now the situation has gone Istomin, the world No “I am afraid of murmuring way beyond what we expected. 40, would have won the unconsciously during the game, If the athletes keep this up, espe- match if he had accepted cially in archery and wrestling, the chair umpire’s judg- which would lead to a penalty.” we believe we can get more than Japan chess player SATOSHI YUKI 70 gold medals,” Lee said. -

May 06, 1950 Cable, A. Ignat'yev to Cde. Gromyko, 'The Partisan Movement in South Korea'

Digital Archive digitalarchive.wilsoncenter.org International History Declassified May 06, 1950 Cable, A. Ignat'yev to Cde. Gromyko, 'The Partisan Movement in South Korea' Citation: “Cable, A. Ignat'yev to Cde. Gromyko, 'The Partisan Movement in South Korea',” May 06, 1950, History and Public Policy Program Digital Archive, AVP RF F. 0102 1950i op. 6 p. 21 pp. 84-108. Translated by Gary Goldberg. https://digitalarchive.wilsoncenter.org/document/114907 Summary: Ignatyev discusses the partisan movement in the rural areas of South Korea. Original Language: Russian Contents: English Translation USSR Embassy in Korea Top Secret Copy Nº 1 6 May 1950 [handwritten]: 15/VII 95 [handwritten]: to Cde. Kurbatov [Stamp]: USSR MFA SECRETARIAT Cde. Gr[omyk]o Top Secret Incoming Nº 4045-?sl? 22.V.1950 TO DEPUTY USSR MINISTER OF FOREIGN AFFAIRS Cde. GROMYKO Copy: Ts. K. Cde. GRIGOR'YAN I am sending material "The Partisan Movement in South Korea" ATTACHMENT: 24-page text. 1+24 112bs 23 V-50 USSR CHARGÉ D'AFFAIRES IN KOREA /signature/ A. IGNAT'YEV Copies to: 1 - Cde. Gromyko 2- Cde. Grigor'yan 3 - to file [date off the page]-V-50 [Handwritten note]: To Cde. ?Kalinin? N. is to check whether it was sent to Cde. Grigor'yan; if not then it needs to be sent. [illegible initials] 20.V [handwritten]: ref. 4045-?sl? Top Secret Attachment to incoming Nº 1126s 23/V 1950 THE PARTISAN MOVEMENT In South Korea (Memorandum) After the failure of a number of attempts to suppress the partisan movement in South Korea at the end of 1949, at the beginning of 1950, the South Korean authorities continued punitive expeditions against the partisans and the civilian population, which sympathizes with them. -

Downloading and Pirating of Dvds Throughout the Regions, Again a Strategy Typically Used by Hollywood Majors

University of Warwick institutional repository: http://go.warwick.ac.uk/wrap A Thesis Submitted for the Degree of PhD at the University of Warwick http://go.warwick.ac.uk/wrap/1153 This thesis is made available online and is protected by original copyright. Please scroll down to view the document itself. Please refer to the repository record for this item for information to help you to cite it. Our policy information is available from the repository home page. ýý Rethinking Media flow under Globalisation: Rising Korean Wave and Korean TV and Film Policy Since 1980s w by Ju Young Kim A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirementsfor the degreeof Doctor of Philosophy in Cultural Policy Studies University of Warwick, Centre for Cultural Policy Studies May 2007 CONTENTS ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS ABSTRACT LIST OF GRAPHS LIST OF TABLES PART I. INTRODUCTION AND METHODOLOGY CHAPTER 1. The Korean Wave: a New Trend in Media Flow ?.......... 1 1.1 THE KOREAN WAVE AS A COUNTER-FLOW 1 ................................... 1.2 OVERVIEW OF THE KOREAN WAVE IN POP CULTURE 5 .................... 1.2.1 Definition and Development of the Korean Wave'Hanryu................. 11 1.2.2 The Impact of'Hanryu............................................................. 24 1.3 METHODOLOGY OF RESEARCH 39 ................................................ CHAPTER 2. Globalisation Media Flow Theory 47 and ................... 2.1 THEORIES ON THE FLOW OF CULTURAL PRODUCTS 47 .................... 2.1.1 Economy Scale 54 of ............................................................... 2.1.2 Cultural Discount 5 8 ............................................................... 2.2 FORMS OF MEDIA FLOW 63 ......................................................... 2.2.1 One Way Flow: Cultural Imperialism 64 ....................................... 2.2.2 Two Multi-Way Flows 69 or ...................................................... 2.3 ISSUES ON THE WORLD TRADE OF CULTURAL PRODUCTS.......... -

The 1394 Governance Code for the Joseon Dynasty of Korea by Jeong Do-Jeon

Revitalization of Ancient Institutions: The 1394 Governance Code for the Joseon Dynasty of Korea by Jeong Do-jeon By Kyongran Chong A thesis submitted to the Victoria University of Wellington in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in the School of Languages and Cultures Victoria University of Wellington (2018) Abstract The Code of Governance for the Joseon Dynasty written by Jeong Do-jeon in 1394 was the first legal document written in justification of a new Korean dynasty. The eminent Korean historian Han Young-woo has credited the political scheme formulated in the Code for promoting democratic ideas of power separation. This study argues that the Code cannot be considered as an attempt to introduce a new power structure in this way, as it was primarily concerned with revitalizing idealized Confucian institutions mobilized by the ideological force of weixin 維新 (revitalization) of guzhi 古制 (ancient institutions) and with creating a society modelled on Confucian values and hierarchical order laid out in the Chinese work, the Zhouli (Rites of Zhou). In his Code, Jeong used this system of government structure as the principle of ancient state institutions, to justify the position of the new Joseon throne, and he also adopted the legal format of the 1331 Yuan law book, Jingshi dadian, in which royal authority took precedence over that of the government. This study emphasizes not only Jeong Do-jeon’s conservative adherence to the continuity of state institutions from the previous Goryeo dynasty (a replica of the Chinese Tang and Song systems), but also the priority he gave to the new Joseon monarch as a stabilizing force within the new dynasty, and argues that the Code was written to ensure continuity and priority, and cannot be considered as an attempt to introduce a new power structure. -

A Study on the Turth Finding Movements Concerning the Reenactment and Amendment of the Jeju 4.3 Special Law

Vo,10 No.2 June 30, 2020 A Study on the Turth Finding Movements Concerning the Reenactment and Amendment of the Jeju 4.3 Special Law Jeong-cheol Yang*, Young-hee Ko**, Michael Saxton*** Abstract Jeju 4.3 refers to a seven year and seven month long period of events; from the 1947 Gwandeokjang Square incident on March 1st, 1947 at Buk Elementary, where a horsed police officer’s mistake lead to casualties that many citizens felt was inadequately investigated to September 21st, 1954, when the Geumjok area of Hallasan was fully opened, officially ending the lock down of Jeju Island. In Jeju, 4.3 was a taboo word. Jeju 4.3 slowly began to rise to the surface of discussion after the collapse of the Syngman Rhee regime in the April Revolution of 1960. In May 1960, the "April 3 Incident Fact-finding Committee," which was led by seven students from Jeju National University, became an organization and began the work of uncovering the truth about Jeju 4.3. In the literary world, Kim Seok-beom's "Hwasando" was published in 1976, and Hyun Ki-Young’s "Aunt Suni", which deals with the massacre in Bukchon was published in 1978, talked about the pain of Jeju 4.3. Later, the political communities tried to console the bereaved families who suffered from national violence through the enactment of the Jeju 4.3 Special Law. As of 2016, discussions on the revision of the Jeju April 3 Special Law were continuously raised and five revisions were submitted to the National Assembly, drawing keen attention from political circles.