David Hawk, the Hidden Gulag IV

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

North Korea Today

North Korea Today Research Institute for the North Korean Society 12th issue Good Friends: Centre for Peace, Human Rights and Refugees 1585-16 Seocho 3dong, Seochogu, Seoul, Korea 137-875 | Ph:+82 2 587 0662 | email: [email protected] Featured Article Hoeryung, Ten Days Worth of Food The December rations were provided from the Distribution are sold in December South Korean aid, and this was told at the official In Hoeryung, the provincial governement of food distributor (shop). Since there were North Hamkyung made a public announcement insufficient amount of rice to be distributed, some through a lecture on the new Public who have food coupons could not buy any rations. Distribution(PDS) system will emerge from 16th It could be seen as the state is trying to of December 2005 to the end of December. The monopolise the rice market – although this is not same was promised in November, but the actual a common situation throughout the country, since distribution did not take place. End of at Hamheung in the North Hamgyung province December 2005, however, 10days worth of rice did not control the black market, but proceed with was distributed for people who have brought the the PDS(Publc Distribution System). ration tickets. Hamheung, in October and November last year, After the Economic Management Improvement the PDS resumed as per normal and grains (rice Measures Policy in July 2002, the government and maize) were all threshed and in normal ration. was planning to provide rice at government This is a comparable change from distributing price(44won ed.), but this time the rice is unthreshed grains while the PDS was suspended. -

Preparing for the Possibility of a North Korean Collapse

CHILDREN AND FAMILIES The RAND Corporation is a nonprofit institution that EDUCATION AND THE ARTS helps improve policy and decisionmaking through ENERGY AND ENVIRONMENT research and analysis. HEALTH AND HEALTH CARE This electronic document was made available from INFRASTRUCTURE AND www.rand.org as a public service of the RAND TRANSPORTATION Corporation. INTERNATIONAL AFFAIRS LAW AND BUSINESS NATIONAL SECURITY Skip all front matter: Jump to Page 16 POPULATION AND AGING PUBLIC SAFETY SCIENCE AND TECHNOLOGY Support RAND Purchase this document TERRORISM AND HOMELAND SECURITY Browse Reports & Bookstore Make a charitable contribution For More Information Visit RAND at www.rand.org Explore the RAND National Security Research Division View document details Limited Electronic Distribution Rights This document and trademark(s) contained herein are protected by law as indicated in a notice appearing later in this work. This electronic representation of RAND intellectual property is provided for non-commercial use only. Unauthorized posting of RAND electronic documents to a non-RAND website is prohibited. RAND electronic documents are protected under copyright law. Permission is required from RAND to reproduce, or reuse in another form, any of our research documents for commercial use. For information on reprint and linking permissions, please see RAND Permissions. This report is part of the RAND Corporation research report series. RAND reports present research findings and objective analysis that address the challenges facing the public and private sectors. All RAND reports undergo rigorous peer review to ensure high standards for re- search quality and objectivity. Preparing for the Possibility of a North Korean Collapse Bruce W. Bennett C O R P O R A T I O N NATIONAL SECURITY RESEARCH DIVISION Preparing for the Possibility of a North Korean Collapse Bruce W. -

North Korea Today” Describing the Way the North Korean People Live As Accurately As Possible

RESEARCH INSTITUTE FOR NORTH KOREAN SOCIETY http://www.goodfriends.or.kr/[email protected] Weekly Newsletter No.374 Priority Release November 2010 [“Good Friends” aims to help the North Korean people from a humanistic point of view and publishes “North Korea Today” describing the way the North Korean people live as accurately as possible. We at Good Friends also hope to be a bridge between the North Korean people and the world.] ___________________________________________________________________________ Central Party Orders to Stop Collecting Rice for Military Provision Sound of Hailing at Farms at the News of No More Collection of Rice for Military Provision “Finally They Think of People” Meat Support Obligation to the Military Also Lifted “At least now we can fill our bellies with potatoes.” ___________________________________________________________________________ Central Party Orders to Stop Collecting Rice for Military Provision Every year when the harvest season approaches there were big conflicts at each regional farm between the military which tries to secure rice for military provision and farmers who refuse to hand over the rice they grew for the past one year. The conflicts are especially severe this year as the yields of harvest decrease because of the cold weather in the spring and the flood in the summer. In the case of North Hamgyong province it was reported that the level of discontent among farmers was serious enough to make the authorities worry. As the damage from flooding was so severe in the granary regions of North and South Hwanghae Provinces and North Pyongan Province it was decided that North Hamgyong Province was to provide rice for military provision first since it had better harvest. -

Pdf | 431.24 Kb

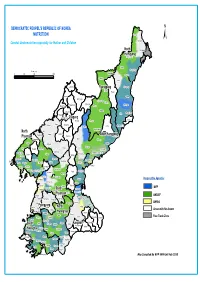

DEMOCRATIC PEOPEL'S REPUBLIC OF KOREA NUTRITION Onsong Kyongwon ± Combat Undernutrition especially for Mother and Children North Kyonghung Hamgyong Hoiryong City Musan Chongjin City Kilometers Taehongdan 050 100 200 Puryong Samjiyon Yonsa Junggang Ryanggang Kyongsong Pochon Paekam Jasong Orang Kimhyongjik Hyesan City Unhung Hwaphyong Kimjongsuk Myonggan Manpo City Samsu Kapsan Janggang Kilju Myongchon Sijung Kanggye City Chagang Rangrim Pungso Hwadae Chosan Wiwon Songgang Pujon Hochon Kimchaek City Kimhyonggwon North Usi Kopung Jonchon South Hamgyong Phyongan Pyokdong Ryongrim Tanchon City Changsong Jangjin Toksong Sakju Songwon Riwon Sinhung Uiju Tongsin Taegwan Tongchang Pukchong Huichon City Sinuiju City Hongwon Sinpho City Chonma Unsan Yonggwang Phihyon Taehung Ryongchon Hyangsan Kusong City Hamhung City Sindo Nyongwon Yomju Tongrim Thaechon Kujang Hamju Sonchon Rakwon Cholsan Nyongbyon Pakchon Tokchon City Kwaksan Jongju City Unjon Jongphyong Kaechon City Yodok Maengsan Anju City Pukchang Mundok Kumya Responsible Agencies Sunchon City Kowon Sukchon Sinyang Sudong WFP Pyongsong City South Chonnae Pyongwon Songchon PhyonganYangdok Munchon City Jungsan UNICEF Wonsan City Taedong Pyongyang City Kangdong Hoichang Anbyon Kangso Sinpyong Popdong UNFPA PyongyangKangnam Thongchon Onchon Junghwa YonsanNorth Kosan Taean Sangwon Areas with No Access Nampo City Hwangju HwanghaeKoksan Hoiyang Suan Pangyo Sepho Free Trade Zone Unchon Yontan Kumgang Kosong Unryul Sariwon City Singye Changdo South Anak Pongsan Sohung Ichon Kangwon Phyonggang Kwail Kimhwa Jaeryong HwanghaeSonghwa Samchon Unpha Phyongsan Sinchon Cholwon Jangyon Rinsan Tosan Ryongyon Sinwon Kumchon Taetan Pongchon Pyoksong Jangphung Haeju City Kaesong City Chongdan Ongjin Paechon Yonan Kaepung Kangryong Map Compiled By WFP VAM Unit Feb 2010. -

Forced Labour in North Korean Prison Camps

forced labour in North Korean Prison Camps Norma Kang Muico Anti-Slavery International 2007 Acknowledgments We would like to thank the many courageous North Koreans who have agreed to be interviewed for this report and shared with us their often difficult experiences. We would also like to thank the following individuals and organisations for their input and assistance: Amnesty International, Baspia, Choi Soon-ho, Citizens’ Alliance for North Korean Human Rights (NKHR), Good Friends, Heo Yejin, Human Rights Watch, Hwang Sun-young, International Crisis Group (ICG), Mike Kaye, Kim Soo-am, Kim Tae-jin, Kim Yoon-jung, Korea Institute for National Unification (KINU), Ministry of Unification (MOU), National Human Rights Commission of Korea (NHRCK), Save the Children UK, Tim Peters and Sarangbang. The Rufford Maurice Laing Foundation kindly funded the research and production of this report as well as connected activities to prompt its recommendations. Forced Labour in North Korean Prison Camps Contents Executive Summary 1 1. Background 2 2. Border Crossing 3 3. Surviving in China 4 Employment 4 Rural Brides 5 4. Forcible Repatriation 6 Police Raids 6 Deportation 8 5. Punishment upon Return 8 Kukga Bowibu (National Security Agency or NSA) 9 Yeshim (Preliminary Examination) 10 Living Conditions 13 The Waiting Game 13 6. Forced Labour in North Korean Prison Camps 14 Nodong Danryundae (Labour Training Camp) 14 Forced Labour 14 Pregnant Prisoners 17 Re-education 17 Living Conditions 17 Food 18 Medical Care 18 Do Jipkyulso (Provincial Detention Centre) 19 Forced Labour 19 Living Conditions 21 Inmin Boansung (People's Safety Agency or PSA) 21 Formal Trials 21 Informal Sentencing 22 Released without Sentence 22 Arbitrary Decisions 22 Kyohwaso (Re-education Camp) 24 Forced Labour 24 Food 24 Medical Care 25 7. -

North Korea Freedom Week

NORTH KOREA FREEDOM WEEK 2013 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Sunday, April 28 – Tuesday, May 6 Seoul, Korea Theme: For the Freedom of North Koreans Report prepared by Kang Seo Chairman of the NKFW 2013: Suzanne Scholte (North Korea Freedom Coalition Chairman) The Honorable Cho Myung-cheol (Saenuri Party) Park Sun-young (Dream Makers for North Korea Director) Co-Sponsor of the NKFW 2013 National Assembly Human Rights Forum Kim Se-yeon, Kim Jin-tae, Kim Choon-jin, Kim Hyun-sook, Kim Hyung-tae, Noh Cheol-rae, Moon Dae- seong, Park In-sook, Seo Sang-gi, Sohn In-choon, Sim Yoon-jo, Lee Jasmin, Jang Yoon-seok, Ha Tae-kyung, Hong Il-pyo (Saenuri Party) National Assembly Unification Future Forum Kang Chang-hee, Kim Kwang-rim, Kim Jong-tae, Seol Hoon, Song Young-geun, Ahn Jong-beom, Lee Byung-seok, Lee Jong-hoon, Lee Ju-young, Jeong Eui-hwa, Joo Ho-young, Choi Bong-hong, Choi Jae- cheon, Han Gi-ho (Saenuri Party) Park Sun-young (Director, Dream Makers for North Korea) Kim Tae-hoon, Esq. Lee Yong-hee (Director, Esther Prayer Group) Jhe Sung-ho (Former NKHR Ambassador, MoFAT) Kim Seok-woo (Former Vice-minister of Foreign Relations, MoFAT) Yoon Yong-nam (Former Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff) Kwon Young-hae (Former Minister of National Defense, MoND) Lim Chang-ho (Pastor, Jangdaehyun Church) Lee Dong-bok (Director, North Korea Democratization Forum) Nishioka Tsutomu Lee Mi-il (President, KWAFU) Event Planning and Preparation Committee Director: Kim Seong Min (Director, FNKR) Planning Committee Co-director Hong Soon Kyung (Director, Committee for the Democratization -

2008년도 한국미생물학회연합 국제학술대회 2008 International Meeting of the Federation of Korean Microbiological Societies October 16-17, 2008 Seoul, Korea

2008년도 한국미생물학회연합 국제학술대회 2008 International Meeting of the Federation of Korean Microbiological Societies October 16-17, 2008 Seoul, Korea Contents Timetable / 일정표 1 Floor Plan / 행사장 안내도 3 Scientific Programs / 학술프로그램 Plenary Lectures / 기조강연 5 Hantaan Prize Award Lecture / 한탄상 수상자 강연 6 Symposia / 심포지아 7 Colloquium / 콜로퀴움 15 Workshop / 워크샵 16 Public Hearing on the Future Research and 17 Development of Microbial Technology Poster Sessions / 포스터세션 18 Scientific Programs of the 9th KJISM 78 Poster Sessions / 포스터세션 81 Author Index / 저자색인 90 Exhibition / 전시회 108 Timetable / 일정표 October 16 (Thursday) Geomungo Hall Daegeum Hall Hall A Hall B Hall C 08:00-09:00 09:00-09:15 Opening Ceremony and Ceremony of Awarding Hantaan Prize (Hall C) S1 S2 S3 S4 09:15-11:15 Strategies of Pathogens Microbial Diversity and Viral Pathogenesis Fungal Bioscience for the Survival in Host Application 11:15-12:00 Plenary Lecture 1 (Hall C) 12:00-12:30 Hantaan Prize Award Lecture (Hall C) 12:30-13:30 Lunch Registration 13:30-14:30 MSK GM KSMy GM 14:30-15:15 Plenary Lecture 2 (Hall B) Poster Session 1 & Exhibition S5 S7 S6 S8 15:15-17:15 Emerging Trends Viral Replication and Regulation of Gene Expression Mushroom Science in Enzyme Screening Gene Expression 17:15-18:00 Plenary Lecture 3 (Hall A) 18:10-18:55 Plenary Lecture 4 (Hall A) 19:00-20:30 Welcome Reception (Hall B+C) October 17 (Friday) Geomungo Hall Daegeum Hall Hall A Hall B Hall C 08:00-09:00 S9 KJS1 S11 S10 09:00-11:00 New Insights into Starter Cultures Microbial Genomics and Emergence of New and Immune System -

Emergency Appeal Final Report Democratic People’S Republic of Korea (DPRK) / North Hamgyong Province: Floods

Emergency Appeal Final Report Democratic People’s Republic of Korea (DPRK) / North Hamgyong Province: Floods Emergency Appeal N°: MDRKP008 Glide n° FL-2016-000097-PRK Date of Issue: 26 March 2018 Date of disaster: 31 August 2016 Operation start date: 2 September 2016 Operation end date: 31 December 2017 Host National Society: Red Cross Society of Democratic Operation budget: CHF 5,037,707 People’s Republic of Korea (DPRK RCS) Number of people affected: 600,000 people Number of people assisted: 110,000 people (27,500 households) N° of National Societies involved in the operation: 19 National Societies: Austrian Red Cross, British Red Cross, Bulgarian Red Cross, China Red Cross, Hong Kong and Macau branches, Czech Red Cross, Danish Red Cross, Finnish Red Cross, German Red Cross, Japanese Red Cross Society, New Zealand Red Cross, Norwegian Red Cross, Red Crescent Society of the Islamic Republic of Iran, Red Cross of Monaco, Spanish Red Cross, Swedish Red Cross, Swiss Red Cross, the Canadian Red Cross Society, the Netherlands Red Cross, the Republic of Korea National Red Cross. The Governments of Austria, Denmark, Finland, Malaysia, Netherlands, Switzerland and Thailand, the European Commission - DG ECHO, and Czech private donors, the Korea NGO Council for Cooperation with North Korea, Movement of One Korea, National YWCA of Korea and the WHO Voluntary Emergency Relief Fund have contributed financially to the operation. N° of other partner organizations involved in the operation: The State Committee for Emergency and Disaster Management (SCEDM), ICRC, UN Organizations, European Union Programme Support Units Summary: This report gives an account of the humanitarian situation and the response carried out by the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea Red Cross Society (DPRK RCS) during the period between 12 September 2016 and 31 December 2017, as per revised Emergency Operation Appeal (EPOA) with the support of International Federation of Red Cross and Red Crescent Societies (IFRC) to meet the needs of floods affected families of North Hamgyong Province in DPRK. -

Searchable PDF Format

- Yangdok Hot Spring Resort - Popular Ceramics Exhibition House - World of Prodigies Silver Ornament A gift presented to President Kim Il Sung by Kaleda Zia, Prime Minister of the People’s Republic of Bangladesh in April 1992 Monthly Journal (766) C O N T E N T S 3 Yangdok Hot Spring Resort 10 Korean Nation’s History of Using Hot Spring 11 Architecture for the People 12 Fruit of Enthusiasm 13 Offensive for Frontal Breakthrough and Increased Production and Economy 14 Old Home at Mangyongdae 17 The Secret Camp on Mt. Paektu 21 Understanding of the People Monthly journal Korea Today is posted on the Internet site www.korean-books.com.kp in English, Russian and Chinese. 1 22 Seventy-fi ve Years of WPK (4) Revolutionary Martyrs Cemetery Tells 23 Relying on Domestic Resources 24 Consumer Changes to Producer 26 Popular Ceramics Exhibition House 28 Nano Cloth Developers Front Cover: Yangdok 29 Target of Developers Hot Spring Resort in the morning 30 World of Prodigies Photo by Kim Kum Sok 32 Record-breaking Achievement in 2019 36 True story I’ll Remain a Winner (7) 38 Promising Sheep Breeding Base 40 Pioneer of Complex Hand-foot Refl ex Therapy 41 Disabled Table Tennis Player 42 National Dog under Good Care 43 Story of Headmaster 44 Glimpse of Japan’s Plunder of Korean Cultural Heritage Back Cover: Moran Hill in spring 46 National Intangible Cultural Heritage (41) Photo by Kim Ji Ye Sijungho Mud Therapy 47 Poetess Ho Ran Sol Hon 13502 ㄱ – 208057 48 Mt Kuwol (3) Edited by Kim Myong Hak Address: Sochon-dong, Sosong District, Pyongyang, DPRK E-mail: fl [email protected] © The Foreign Language Magazines 2020 2 YYangdokangdok HHotot SSpringpring RResortesort No. -

Global Proxy Voting Records

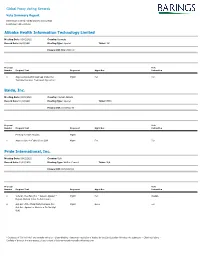

Global Proxy Voting Records Vote Summary Report Date range covered: 03/01/2021 to 03/31/2021 Location(s): All Locations Alibaba Health Information Technology Limited Meeting Date: 03/01/2021 Country: Bermuda Record Date: 02/23/2021 Meeting Type: Special Ticker: 241 Primary ISIN: BMG0171K1018 Proposal Vote Number Proposal Text Proponent Mgmt Rec Instruction 1 Approve Revised Annual Cap Under the Mgmt For For Technical Services Framework Agreement Baidu, Inc. Meeting Date: 03/01/2021 Country: Cayman Islands Record Date: 01/28/2021 Meeting Type: Special Ticker: BIDU Primary ISIN: US0567521085 Proposal Vote Number Proposal Text Proponent Mgmt Rec Instruction Meeting for ADR Holders Mgmt 1 Approve One-to-Eighty Stock Split Mgmt For For Pride International, Inc. Meeting Date: 03/01/2021 Country: USA Record Date: 12/01/2020 Meeting Type: Written Consent Ticker: N/A Primary ISIN: US74153QAJ13 Proposal Vote Number Proposal Text Proponent Mgmt Rec Instruction 1 Vote On The Plan (For = Accept, Against = Mgmt For Abstain Reject; Abstain Votes Do Not Count) 2 Opt Out of the Third-Party Releases (For = Mgmt None For Opt Out, Against or Abstain = Do Not Opt Out) * Instances of "Do Not Vote" are normally owing to: - Share-blocking - temporary restriction of trading by the Sub-Custodian following vote submission - Client restrictions - Conflicts of Interest. For any queries, please contact [email protected] Global Proxy Voting Records Vote Summary Report Date range covered: 03/01/2021 to 03/31/2021 Location(s): All Locations The -

The Situation Further to Determine If External Assistance Is Needed

Information bulletin Democratic People’s Republic of Korea: Floods Information Bulletin n° 1 GLIDE n° FL-2013-000081-PRK 26 July 2013 Text box for brief photo caption. Example: In February 2007, the This bulletin is being issued for information Colombian Red Cross Society distributed urgently needed only, and reflects the current situation and materials after the floods and slides in Cochabamba. IFRC (Arial details available at this time. The 8/black colour) Democratic People’s Republic of Korea Red Cross Society (DPRK RCS), with the support of the International Federation of Red Cross and Red Crescent Societies (IFRC) is assessing the situation further to determine if external assistance is needed. Since 12-22 July 2013, most parts of DPRK were hit by consecutive floods and landslides caused by torrential rains. As of 23 July, DPRK government data reports 28 persons dead, 2 injured and 18 missing. A total of 3,742 families have lost their houses due to total and partial destruction and 49,052 people have been displaced. Red Cross volunteers were mobilized for early Red Cross volunteers are distributing the relief items to flood affected people in Anju City, South Pyongan province. Photo: DPRK RCS. warning and evacuation, search and rescue, first aid service, damage and need assessment, and distribution of relief items. The DPRK RCS with the support of IFRC has released 2,690 emergency relief kits, including quilts, cooking sets, tarpaulins, jerry cans, hygiene kits and water purification tablets which were distributed to 10,895 beneficiaries in Tosan County, North Hwanghae province and Anju City, South Pyongan province. -

Understanding Korea 8 Tourism & Investment

UNDERSTANDING KOREA 8 TOURISM & INVESTMENT PYONGYANG, KOREA Juche 106 (2017) UNDERSTANDING KOREA 8 TOURISM & INVESTMENT Foreign Languages Publishing House Pyongyang, Korea Juche 106 (2017) CONTENTS 1. Tourism Resources.................................................1 2. Major Tourist Attractions .......................................1 3. Pyongyang, a Tourist Destination...........................2 4. Monumental Structures in Pyongyang....................2 5. Grand Monument on Mansu Hill............................2 6. Tower of the Juche Idea..........................................3 7. Monument to Party Founding .................................4 8. Chollima Statue.......................................................5 9. Arch of Triumph .....................................................6 10. Victorious Fatherland Liberation War Museum and Monument to the Victorious Fatherland Liberation War ....................7 11. Monument to the Three Charters for National Reunification......................................8 12. Parks and Pleasure Grounds in Pyongyang.............9 13. Moran Hill ............................................................10 14. Kaeson Youth Park ...............................................10 15. Rungna People’s Pleasure Ground........................11 16. Pyongyang, a Time-Honoured City ......................12 17. Royal Tombs in Pyongyang..................................13 18. Mausoleum of King Tangun................................. 13 19. Mausoleum of King Tongmyong.......................... 14 20.