ABSTRACT CULCLASURE, DAVID NEWTON. the Supply of The

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

In the Eye of the Stakeholder Changes in Perceptions Of

Ecosystem Services ∎ (∎∎∎∎) ∎∎∎–∎∎∎ Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Ecosystem Services journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/ecoser In the eye of the stakeholder: Changes in perceptions of ecosystem services across an international border Daniel E. Orenstein a,n, Elli Groner b a Faculty of Architecture and Town Planning, Technion – Israel Institute of Technology, Haifa 32000, Israel b Dead Sea and Arava Science Center, DN Chevel Eilot, 88840, Israel article info abstract Article history: Integration of the ecosystem service (ES) concept into policy begins with an ES assessment, including Received 24 August 2013 identification, characterization and valuation of ES. While multiple disciplinary approaches should be Received in revised form integrated into ES assessments, non-economic social analyses have been lacking, leading to a knowledge 11 February 2014 gap regarding stakeholder perceptions of ES. Accepted 9 April 2014 We report the results of trans-border research regarding how local residents value ES in the Arabah Valley of Jordan and Israel. We queried rural and urban residents in each of the two countries. Our Keywords: questions pertained to perceptions of local environmental characteristics, involvement in outdoor Ecosystem services activities, and economic dependency on ES. Stakeholders Both a political border and residential characteristics can define perceptions of ES. General trends Trans-border regarding perceptions of environmental characteristics were similar across the border, but Jordanians Hyper-arid ecosystems fi Social research methods tended to rank them less positively than Israelis; likewise, urban residents tended to show less af nity to environmental characteristics than rural residents. Jordanians and Israelis reported partaking in distinctly different sets of outdoor activities. -

Itinerary Is Subject to Change. •

Itinerary is Subject to Change. • Welcome to Israel! This evening, meet in the lobby of the new Royal Beach Hotel in Tel Aviv. After a short introduction, board the bus and head to a special venue for an opening dinner and introduction to the mission. Several special guests will join us for the evening as well. Overnight, Royal Beach Hotel, Tel Aviv Tel Aviv • Following breakfast, transfer to the airport for a flight to Eilat. Upon arrival, proceed to Timna Park. Pass through the front gates to the newly built chronosphere and become immersed in a fascinating 360-degree multimedia experience called the Mines of Time. Through a dramatic audio-visual computer simulation and state-of-the-art animation, learn about ancient Egyptian and Midianite cultures dating from the time of the Exodus - a prelude to what we’ll encounter further into the park. Solomon’s Pillars at Timna Park Following lunch by Timna Park’s lake, continue to Kibbutz Grofit for a visit to the Red Mountain Therapeutic Riding Center, which focuses on children from Israel suffering from mild to severe emotional and physical disabilities. A representative from the center will lead a tour of the facility and provide an update of the center’s current activities. Proceed to Kibbutz Yahel, a vibrant agricultural kibbutz with a focus on the tourism industry. JNF is continuing its long-standing partnership with Kibbutz Yahel and Mushroom at Timna Park developing a recreational and educational park in the heart of the Southern Arava that will be a tranquil, green retreat for tourists and travelers. -

Mammals of Jordan

© Biologiezentrum Linz/Austria; download unter www.biologiezentrum.at Mammals of Jordan Z. AMR, M. ABU BAKER & L. RIFAI Abstract: A total of 78 species of mammals belonging to seven orders (Insectivora, Chiroptera, Carni- vora, Hyracoidea, Artiodactyla, Lagomorpha and Rodentia) have been recorded from Jordan. Bats and rodents represent the highest diversity of recorded species. Notes on systematics and ecology for the re- corded species were given. Key words: Mammals, Jordan, ecology, systematics, zoogeography, arid environment. Introduction In this account we list the surviving mammals of Jordan, including some reintro- The mammalian diversity of Jordan is duced species. remarkable considering its location at the meeting point of three different faunal ele- Table 1: Summary to the mammalian taxa occurring ments; the African, Oriental and Palaearc- in Jordan tic. This diversity is a combination of these Order No. of Families No. of Species elements in addition to the occurrence of Insectivora 2 5 few endemic forms. Jordan's location result- Chiroptera 8 24 ed in a huge faunal diversity compared to Carnivora 5 16 the surrounding countries. It shelters a huge Hyracoidea >1 1 assembly of mammals of different zoogeo- Artiodactyla 2 5 graphical affinities. Most remarkably, Jordan Lagomorpha 1 1 represents biogeographic boundaries for the Rodentia 7 26 extreme distribution limit of several African Total 26 78 (e.g. Procavia capensis and Rousettus aegypti- acus) and Palaearctic mammals (e. g. Eri- Order Insectivora naceus concolor, Sciurus anomalus, Apodemus Order Insectivora contains the most mystacinus, Lutra lutra and Meles meles). primitive placental mammals. A pointed snout and a small brain case characterises Our knowledge on the diversity and members of this order. -

Israel's Conquest of Canaan: Presidential Address at the Annual Meeting, Dec

Israel's Conquest of Canaan: Presidential Address at the Annual Meeting, Dec. 27, 1912 Author(s): Lewis Bayles Paton Reviewed work(s): Source: Journal of Biblical Literature, Vol. 32, No. 1 (Apr., 1913), pp. 1-53 Published by: The Society of Biblical Literature Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/3259319 . Accessed: 09/04/2012 16:53 Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at . http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. The Society of Biblical Literature is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Journal of Biblical Literature. http://www.jstor.org JOURNAL OF BIBLICAL LITERATURE Volume XXXII Part I 1913 Israel's Conquest of Canaan Presidential Address at the Annual Meeting, Dec. 27, 1912 LEWIS BAYLES PATON HARTFORD THEOLOGICAL SEMINARY problem of Old Testament history is more fundamental NO than that of the manner in which the conquest of Canaan was effected by the Hebrew tribes. If they came unitedly, there is a possibility that they were united in the desert and in Egypt. If their invasions were separated by wide intervals of time, there is no probability that they were united in their earlier history. Our estimate of the Patriarchal and the Mosaic traditions is thus conditioned upon the answer that we give to this question. -

The Legal Status of Tiran and Sanafir Islands Rajab, 1438 - April 2017

22 Dirasat The Legal Status of Tiran and Sanafir Islands Rajab, 1438 - April 2017 Askar H. Enazy The Legal Status of Tiran and Sanafir Islands Askar H. Enazy 4 Dirasat No. 22 Rajab, 1438 - April 2017 © King Faisal Center for Research and Islamic Studies, 2017 King Fahd National Library Cataloging-In-Publication Data Enazy, Askar H. The Legal Status of Tiran and Sanafir Island. / Askar H. Enazy, - Riyadh, 2017 76 p ; 16.5 x 23 cm ISBN: 978-603-8206-26-3 1 - Islands - Saudi Arabia - History 2- Tiran, Strait of - Inter- national status I - Title 341.44 dc 1438/8202 L.D. no. 1438/8202 ISBN: 978-603-8206-26-3 Table of Content Introduction 7 Legal History of the Tiran-Sanafir Islands Dispute 11 1928 Tiran-Sanafir Incident 14 The 1950 Saudi-Egyptian Accord on Egyptian Occupation of Tiran and Sanafir 17 The 1954 Egyptian Claim to Tiran and Sanafir Islands 24 Aftermath of the 1956 Suez Crisis: Egyptian Abandonment of the Claim to the Islands and Saudi Assertion of Its Sovereignty over Them 26 March–April 1957: Saudi Press Statement and Diplomatic Note Reasserting Saudi Sovereignty over Tiran and Sanafir 29 The April 1957 Memorandum on Saudi Arabia’s “Legal and Historical Rights in the Straits of Tiran and the Gulf of Aqaba” 30 The June 1967 War and Israeli Reoccupation of Tiran and Sanafir Islands 33 The Status of Tiran and Sanafir Islands in the Egyptian-Israeli Peace Treaty of 1979 39 The 1988–1990 Egyptian-Saudi Exchange of Letters, the 1990 Egyptian Decree 27 Establishing the Egyptian Territorial Sea, and 2016 Statements by the Egyptian President -

Palestine About the Author

PALESTINE ABOUT THE AUTHOR Professor Nur Masalha is a Palestinian historian and a member of the Centre for Palestine Studies, SOAS, University of London. He is also editor of the Journal of Holy Land and Palestine Studies. His books include Expulsion of the Palestinians (1992); A Land Without a People (1997); The Politics of Denial (2003); The Bible and Zionism (Zed 2007) and The Pales- tine Nakba (Zed 2012). PALESTINE A FOUR THOUSAND YEAR HISTORY NUR MASALHA Palestine: A Four Thousand Year History was first published in 2018 by Zed Books Ltd, The Foundry, 17 Oval Way, London SE11 5RR, UK. www.zedbooks.net Copyright © Nur Masalha 2018. The right of Nur Masalha to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act, 1988. Typeset in Adobe Garamond Pro by seagulls.net Index by Nur Masalha Cover design © De Agostini Picture Library/Getty All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying or otherwise, without the prior permission of Zed Books Ltd. A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library. ISBN 978‑1‑78699‑272‑7 hb ISBN 978‑1‑78699‑274‑1 pdf ISBN 978‑1‑78699‑275‑8 epub ISBN 978‑1‑78699‑276‑5 mobi CONTENTS Acknowledgments vii Introduction 1 1. The Philistines and Philistia as a distinct geo‑political entity: 55 Late Bronze Age to 500 BC 2. The conception of Palestine in Classical Antiquity and 71 during the Hellenistic Empires (500‒135 BC) 3. -

Aspects of Iconography in Byzantine Cappadocia

RESEARCH ARTICLE European Journal of Theology and Philosophy www.ej-theology.org Aspects of Iconography in Byzantine Cappadocia E. Ene D-Vasilescu ABSTRACT The main novelty my article brings concerns a particular iconographic motif: that known as the ‘trial by the water of reproach’. In the few cases Published Online: August 17, 2021 where this is rendered, usually only Mary is presented as undergoing this ISSN: 2736-5514 test, but in Cappadocian art Joseph is also subjected to it. DOI :10.24018/theology.2021.1.4.35 Additionally, to this visual topic, another one that is rarely depicted will be introduced and commented upon: that known as ‘Christ’s first bath’. E. Ene D-Vasilescu* I will provide a particular example: the fresco which constitutes part of (e-mail: elena.ene-yahoo.co.uk) the decoration that embellishes the walls of Karabaş Kilise/ ‘The Big Church’ in Soğanlı Valley, southern Cappadocia. *Corresponding Author A few images – one of them never published before – have been included within this publication. Keywords: Byzantium, Byzantine frescoes, Cappadocia, Constantine VII Porphyrogenetus. Karabaş church in the Soğanlı Valley, Phocas family, the Old and New Tokalı churches in Göreme. Cappadocians occupied a region from Mount Taurus (Fig. 1) I. INTRODUCTION to the vicinity of the Pontus Euxine (the Black Sea) [1]. The current piece is concerned with two rare visual motifs Therefore, the province was bordered in the south by the that can be found among other images which decorate Taurus Mountains that separate it from Cilicia to the east by churches established in Cappadocia under Byzantine rule. -

Joshua 12-13.Pdf

Joshua 11:23 So Joshua took the whole land, according to all that the LORD had spoken to Moses. And Joshua gave it for an inheritance to Israel according to their tribal allotments. And the land had rest from war. I. Don’t Forget 12 Now these are the kings of the land whom the people of Israel defeated and took possession of their land beyond the Jordan towards the sunrise, from the Valley of the Arnon to Mount Hermon, with all the Arabah eastwards: 2 Sihon king of the Amorites who lived at Heshbon and ruled from Aroer, which is on the edge of the Valley of the Arnon, and from the middle of the valley as far as the river Jabbok, the boundary of the Ammonites, that is, half of Gilead, 3 and the Arabah to the Sea of Chinneroth eastwards, and in the direction of Beth-jeshimoth, to the Sea of the Arabah, the Salt Sea, southwards to the foot of the slopes of Pisgah; I. Don’t Forget 4 and Og[a] king of Bashan, one of the remnant of the Rephaim, who lived at Ashtaroth and at Edrei 5 and ruled over Mount Hermon and Salecah and all Bashan to the boundary of the Geshurites and the Maacathites, and over half of Gilead to the boundary of Sihon king of Heshbon. 6 Moses, the servant of the LORD, and the people of Israel defeated them. And Moses the servant of the LORD gave their land for a possession to the Reubenites and the Gadites and the half-tribe of Manasseh. -

AVINOAM MEIR Birth: November 1, 1946 Place of Birth: Israel Address

1 CURRICULUM VITAE (January 2021) PERSONAL DETAILS Name: AVINOAM MEIR Birth: November 1, 1946 Place of Birth: Israel Address: (w) Department of Geography and Environmental Development Ben-Gurion University of the Negev Beer-Sheva, Israel Tel.: 0528795994 E-mail: ameir@ bgu.ac.il (h) 24/50 Efraim Katzir, Hod HaSharon, ISRAEL, 4528253 EDUCATION B.A.: 1972, Tel Aviv University, Israel, Geography (cum laude). M.A.: 1975, University of Cincinnati, Ohio, USA, Geography Thesis Title: Spatial diffusion of Passenger Cars in Ohio: A Study in Pattern and Determinants (Advisor: Professor Robert B. South). Ph.D.: 1977, University of Cincinnati, Ohio, USA, Geography Dissertation Title: Diffusion, Spread, and Spatial Innovation Transmission Processes: The Adoption of Industry among Kibbutzim in Israel as a Case Study (Advisor: Professor Roger M. Selya). EMPLOYMENT HISTORY 1971-72: Teaching Assistant, Department of Geography, Tel Aviv University, Israel. 1974-77: Teaching Assistant, Department of Geography, University of Cincinnati, USA. 1977-78: Lecturer, HaNegev College and Beit-Berl College, Israel (part-time). 1977-81: Lecturer, Department of Geography, Ben-Gurion University of the Negev. 2 1979-82: Research Fellow, Blaustein Institute for Desert Research, Sde, Boker, Ben-Gurion University of the Negev. 1981- 87: Senior Lecturer, Department of Geography, Ben-Gurion University of the Negev (Tenure: 1981). 1984-85: Visiting Professor, Department of Geography, University of California, Los Angeles, USA. 1987-88: Research Fellow, Blaustein Institute for Desert Research, Sde Boker, Ben-Gurion University of the Negev. 1987-96: Associate Professor, Department of Geography, Ben-Gurion University of the Negev. 1989-96: Associate Professor, Sapir College, Israel (part-time). -

The Names and Boundaries of Eretz-Israel (Palestine) As Reflections of Stages in Its History

THE NAMES AND BOUNDARIES OF ERETZ-ISRAEL (PALESTINE) AS REFLECTIONS OF STAGES IN ITS HISTORY GIDEON BIGER INTRODUCTION Classical historical geography focuses on research of the boundaries of the various states, along with the historical development of these boundaries over time. Edward Freeman, in his book written in 1881 and entitled The Historical Geography of Europe, defines the nature of historical-geographical research as follows: "The work which we have now before us is to trace out the extent of territory which the different states and nations have held at different times in the world's history, to mark the different boundaries which the same country has had and the different meanings in which the same name has been used." The author further claims that "it is of great importance carefully to make these distinctions, because great mistakes as to the facts of history are often caused through men thinking and speaking as if the names of different countries have always meant exactly the same extent of territory. "1 Although this approach - which regards research on boundaries as the essence of historical geography- is not accepted at present, the claim that it is necessary to define the extent of territory over history is as valid today as ever. It is impossible to discuss the development of any geographical area having political and territorial significance without knowing and understanding its physical extent. Of no less significance for such research are the names attached to any particular expanse. The naming of a place is the first step in defining it politically and historically. -

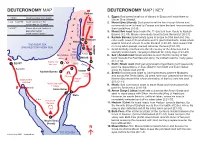

DEUTERONOMY MAP DEUTERONOMY MAP | KEY Bashan

DEUTERONOMY MAP DEUTERONOMY MAP | KEY Bashan 1446 BC Israel’s exodus from Egypt 1. Egypt: God saves Israel out of slavery in Egypt and leads them to Mount Sinai (Horeb). 1446 - 1406 BC Israel wanders in the Edrei 2. Mount Sinai (Horeb): God gives Israel the law through Moses and wilderness for 40 years commands Israel to head to Canaan and take the land he promised to 1406 BC Moses dies and Joshua is their forefathers (1:6-8). appointed leader 3. Mount Seir road: Israel make the 11-day trek from Horeb to Kadesh Israel enters Canaan Barnea (1:2,19). Moses commands Israel to take the land (1:20-21). Jordan River 4. Kadesh Barnea: Israel sends spies to scope out the land and they 12 Hesbon return with news of its goodness and its giant inhabitants. Israel rebels Nebo 11 against God and refuses to enter the land (1:22-33). God swears that THE Great SEA no living adult (except Joshua) will enter the land (1:34-40). (THE MEDITERRANEAN SEA) 13 Salt Jahaz 5. Israel defiantly marches into the hill country of the Amorites and is CANAAN Sea soundly beaten back, camping in Kadesh for many days (1:41-45). Arnon 10 AMMON Ammorites (Dead 6. Seir | Arabah road: Israel wanders around the hill country of Seir Sea) MOAB back towards the Red Sea and along the Arabah road for many years Spying out 9 (2:1; 2:14). 1 5 EGYPT the land SEIR Zered 7. Elath | Moab road: God instructs Israel to head back north peacefully 6 past the descendants of Esau (Edom) from Elath and Ezion Geber Succoth 8 along the Moab road (2:2-8). -

7/7/19 the Reign of Uzziah 2Chron. 26:1-23 There Are Some Leader That

1 2 7/7/19 2. The industrious spirit, “He built Elath and restored it to Judah, after the king rested The Reign of Uzziah with his fathers.” vs. 2 2Chron. 26:1-23 3. The age and length of reign of Uzziah, “Uzziah was sixteen years old when he There are some leader that stand out in history for became king, and he reigned fifty-two years their excellence, then there are others though they in Jerusalem.” vs. 3 a-b were excellent made a foolish decision or other and a. He is the second longest reigning king of that is all they are remembered for, this is Uzziah. Judah 52 years. * Like Ex-President Richard Nixon, he is remembered b. Manaaseh is first 55 years. 2Chron. 33:1- for Watergate. 20 4. The mother of Uzziah, “His mother’s name So the reign of Uzziah as it is revealed from three was Jecholiah of Jerusalem.” vs. 3c perspectives according to God. 2Chron. 26:1-23 * Jecholiah “Y@kolyah”, means “Yahweh I. The reign of Uzziah over Judah. vs. 1-5 is able”, what a wonderful name. II. The rule of Uzziah for Judah. vs. 6-15 III. The wrongdoing of Uzziah. vs. 16-23 B. The godly character of Uzziah. vs. 4-5 1. The godly conduct of Uzziah, “And he did I. The reign of Uzziah over Judah. vs. 1-5 what was right in the sight of the LORD, * The parallel passages. 2Kings 14:21-22; 15:1-7 according to all that his father Amaziah had done.” vs.