Critical Theory and Jean-Luc Godard's Philosophy of the Image

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Goodbye Cinema, Hello Cinephilia Other Books by Jonathan Rosenbaum

Goodbye Cinema, Hello Cinephilia Other Books by Jonathan Rosenbaum Rivette: Texts and Interviews (editor, 1977) Orson Welles: A Critical View, by André Bazin (editor and translator, 1978) Moving Places: A Life in the Movies (1980) Film: The Front Line 1983 (1983) Midnight Movies (with J. Hoberman, 1983) Greed (1991) This Is Orson Welles, by Orson Welles and Peter Bogdanovich (editor, 1992) Placing Movies: The Practice of Film Criticism (1995) Movies as Politics (1997) Another Kind of Independence: Joe Dante and the Roger Corman Class of 1970 (coedited with Bill Krohn, 1999) Dead Man (2000) Movie Wars: How Hollywood and the Media Limit What Films We Can See (2000) Abbas Kiarostami (with Mehrmax Saeed-Vafa, 2003) Movie Mutations: The Changing Face of World Cinephilia (coedited with Adrian Martin, 2003) Essential Cinema: On the Necessity of Film Canons (2004) Discovering Orson Welles (2007) The Unquiet American: Trangressive Comedies from the U.S. (2009) Goodbye Cinema, Hello Cinephilia Film Culture in Transition Jonathan Rosenbaum the university of chicago press | chicago and london Jonathan Rosenbaum wrote for many periodicals (including the Village Voice, Sight and Sound, Film Quarterly, and Film Comment) before becoming principal fi lm critic for the Chicago Reader in 1987. Since his retirement from that position in March 2008, he has maintained his own Web site and continued to write for both print and online publications. His many books include four major collections of essays: Placing Movies (California 1995), Movies as Politics (California 1997), Movie Wars (a cappella 2000), and Essential Cinema (Johns Hopkins 2004). The University of Chicago Press, Chicago 60637 The University of Chicago Press, Ltd., London © 2010 by The University of Chicago All rights reserved. -

JEAN-LUC GODARD: SON+IMAGE Fact Sheet

The Museum of Modern Art For Immediate Release August 1992 FACT SHEET EXHIBITION JEAN-LUC GODARD: SON+IMAGE DATES October 30 - November 30, 1992 ORGANIZATION Laurence Kardish, curator, Department of Film, with the collaboration of Mary Lea Bandy, director, Department of Film, and Barbara London, assistant curator, video, Department of Film, The Museum of Modern Art; and Colin Myles MacCabe, professor of English, University of Pittsburgh, and head of research and information, British Film Institute. CONTENT Jean-Luc Godard, one of modern cinema's most influential artists, is equally important in the development of video. JEAN-LUC GODARD: SON+IMAGE traces the relationship between Godard's films and videos since 1974, from the films Ici et ailleurs (1974) and Numero Deux (1975) to episodes from his video series Histoire(s) du Cinema (1989) and the film Nouvelle Vague (1990). Godard's work is as visually and verbally dense with meaning during this period as it was in his revolutionary films of the 1960s. Using deconstruction and reassemblage in works such as Puissance de la Parole (video, 1988) and Allemagne annee 90 neuf zero (film, 1991), Godard invests the sound/moving image with a fresh aesthetic that is at once mysterious and resonant. Film highlights of the series include Sauve qui peut (la vie) (1979), First Name: Carmen (1983), Hail Mary (1985), Soigne ta droite (1987), and King Lear (1987), among others. Also in the exhibition are Scenario du film Passion (1982), the video essay about the making of the film Passion (1982), which is also included, and the videos he created in collaboration with Anne-Marie Mieville, Soft and Hard (1986) and the series made for television, Six fois deux/Sur et sous la communication (1976). -

The Inventory of the Richard Roud Collection #1117

The Inventory of the Richard Roud Collection #1117 Howard Gotlieb Archival Research Center ROOD, RICHARD #1117 September 1989 - June 1997 Biography: Richard Roud ( 1929-1989), as director of both the New York and London Film Festivals, was responsible for both discovering and introducing to a wider audience many of the important directors of the latter half th of the 20 - century (many of whom he knew personally) including Bernardo Bertolucci, Robert Bresson, Luis Buiiuel, R.W. Fassbinder, Jean-Luc Godard, Werner Herzog, Terry Malick, Ermanno Ohni, Jacques Rivette and Martin Scorsese. He was an author of books on Jean-Marie Straub, Jean-Luc Godard, Max Ophuls, and Henri Langlois, as well as the editor of CINEMA: A CRITICAL DICTIONARY. In addition, Mr. Roud wrote extensive criticism on film, the theater and other visual arts for The Manchester Guardian and Sight and Sound and was an occasional contributor to many other publications. At his death he was working on an authorized biography of Fran9ois Truffaut and a book on New Wave film. Richard Roud was a Fulbright recipient and a Chevalier in the Legion of Honor. Scope and contents: The Roud Collection (9 Paige boxes, 2 Manuscript boxes and 3 Packages) consists primarily of book research, articles by RR and printed matter related to the New York Film Festival and prominent directors. Material on Jean-Luc Godard, Francois Truffaut and Henri Langlois is particularly extensive. Though considerably smaller, the Correspondence file contains personal letters from many important directors (see List ofNotable Correspondents). The Photographs file contains an eclectic group of movie stills. -

La Première Nuit D'amour Du Cinéma Français » : Les Amants De

Diplôme national de master Domaine - Sciences humaines et sociales Mention – Histoire civilisations patrimoine 2017 Spécialité - Cultures de l’écrit et de l’image juin / « La première nuit d’amour du cinéma français » : Les Amants de Louis Malle et ses réceptions émoire de master 1 master de émoire M Paul Bacharach Sous la direction de Evelyne Cohen Professeure d’histoire et anthropologie culturelles (XXe siècle) – École nationale supérieure des Sciences de l’information et des bibliothèques (ENSSIB – Université de Lyon) Remerciements Je tiens tout d’abord à remercier Mme Evelyne Cohen, ma directrice de mémoire, qui a montré un intérêt, une confiance et une exigence sans lesquels ce travail n’aurait pas été possible. Je remercie les personnels de la Bibliothèque Raymond Chirat de l’Institut Lumière et de la Bibliothèque du Film de la Cinémathèque Française qui m’ont orienté dans mes recherches. J’adresse ma gratitude aux amis qui m’ont aidé, en m’adressant des conseils, en discutant de mon travail, et en me relisant. J’exprime enfin un remerciement particulier à Pierre Laborie, qui avait pris la peine de me répondre, et à Nadine Cadot-Laborie, qui m’a livré son joli témoignage. BACHARACH Paul | Master I | Mémoire | juin 2017 - 3 – Résumé : Les Amants est un film de Louis Malle réalisé en 1958 et adapté du conte Point de lendemain, de Vivant Denon (1812). Il raconte comment une femme mariée issue de la bourgeoisie rencontre un inconnu, passe une nuit avec lui, et quitte sa famille pour vivre une histoire d’amour. Le film provoqua un scandale international qui commença lors de sa présentation au festival de Venise de septembre 1958. -

Performance in and of the Essay Film: Jean-Luc Godard Plays Jean-Luc Godard in Notre Musique (2004) Laura Rascaroli University College Cork

SFC_9.1_05_art_Rascaroli.qxd 3/6/09 8:49 AM Page 49 Studies in French Cinema Volume 9 Number 1 © 2009 Intellect Ltd Article. English language. doi: 10.1386/sfc.9.1.49/1 Performance in and of the Essay film: Jean-Luc Godard plays Jean-Luc Godard in Notre musique (2004) Laura Rascaroli University College Cork Abstract Keywords The ‘essay film’ is an experimental, hybrid, self-reflexive form, which crosses Essay film generic boundaries and systematically employs the enunciator’s direct address to Jean-Luc Godard the audience. Open and unstable by nature, it articulates its rhetorical concerns in performance a performative manner, by integrating into the text the process of its own coming communicative into being, and by allowing answers to emerge in the position of the embodied negotiation spectator. My argument is that performance holds a privileged role in Jean-Luc authorial self- Godard’s essayistic cinema, and that it is, along with montage, the most evident representation site of the negotiation between film-maker and film, audience and film, film and Notre musique meaning. A fascinating case study is provided by Notre musique/Our Music (2004), in which Godard plays himself. Communicative negotiation is, I argue, both Notre musique’s subject matter and its textual strategy. It is through the variation in registers of acting performances that the film’s ethos of unreserved openness and instability is fully realised, and comes to fruition for its embodied spectator. In a rare scholarly contribution on acting performances in documentary cinema, Thomas Waugh reminds us that the classical documentary tradition took the notion of performance for granted; indeed, ‘semi-fictive characteri- zation, or “personalization,”… seemed to be the means for the documentary to attain maturity and mass audiences’ (Waugh 1990: 67). -

Une Année Studieuse

Extrait de la publication DU MÊME AUTEUR Aux Éditions Gallimard DES FILLES BIEN ÉLEVÉES MON BEAU NAVIRE (Folio no 2292) MARIMÉ (Folio no 2514) CANINES (Folio no 2761) HYMNES À L’AMOUR (Folio no 3036) UNE POIGNÉE DE GENS. Grand Prix du roman de l’Académie française 1998 (Folio no 3358) AUX QUATRE COINS DU MONDE (Folio no 3770) SEPT GARÇONS (Folio no 3981) JE M’APPELLE ÉLISABETH (Folio no 4270) L’ÎLE. Nouvelle extraite du recueil DES FILLES BIEN ÉLEVÉES (Folio 2 € no 4674) JEUNE FILLE (Folio no 4722) MON ENFANT DE BERLIN (Folio no 5197) Extrait de la publication une année studieuse Extrait de la publication Extrait de la publication ANNE WIAZEMSKY UNE ANNÉE STUDIEUSE roman GALLIMARD © Éditions Gallimard, 2012. Extrait de la publication À Florence Malraux Extrait de la publication Un jour de juin 1966, j’écrivis une courte lettre à Jean-Luc Godard adressée aux Cahiers du Cinéma, 5 rue Clément-Marot, Paris 8e. Je lui disais avoir beaucoup aimé son dernier i lm, Masculin Féminin. Je lui disais encore que j’aimais l’homme qui était derrière, que je l’aimais, lui. J’avais agi sans réaliser la portée de certains mots, après une conversation avec Ghislain Cloquet, rencontré lors du tournage d’Au hasard Balthazar de Robert Bresson. Nous étions demeurés amis, et Ghislain m’avait invitée la veille à déjeuner. C’était un dimanche, nous avions du temps devant nous et nous étions allés nous promener en Normandie. À un moment, je lui parlai de Jean-Luc Godard, de mes regrets au souvenir de trois rencontres « ratées ». -

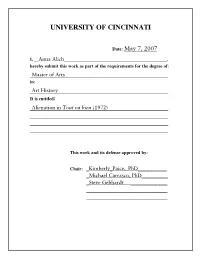

University of Cincinnati

UNIVERSITY OF CINCINNATI Date: May 7, 2007 I, __Anna Alich_____________________________________________, hereby submit this work as part of the requirements for the degree of: Master of Arts in: Art History It is entitled: Alienation in Tout va bien (1972) This work and its defense approved by: Chair: _Kimberly_Paice, PhD___________ _Michael Carrasco, PhD__________ _Steve Gebhardt ______________ _______________________________ _______________________________ Alienation in Jean-Luc Godard’s Tout Va Bien (1972) A thesis presented to the Art History Faculty of the College of Design, Architecture, Art, and Planning University of Cincinnati in candidacy for the degree of Master of Arts in Art History Anna Alich May 2007 Advisor: Dr. Kimberly Paice Abstract Jean-Luc Godard’s (b. 1930) Tout va bien (1972) cannot be considered a successful political film because of its alienated methods of film production. In chapter one I examine the first part of Godard’s film career (1952-1967) the Nouvelle Vague years. Influenced by the events of May 1968, Godard at the end of this period renounced his films as bourgeois only to announce a new method of making films that would reflect the au courant French Maoist politics. In chapter two I discuss Godard and the Dziga Vertov Group’s last film Tout va bien. This film displays a marked difference in style from Godard’s earlier films, yet does not display a clear understanding of how to make a political film of this measure without alienating the audience. In contrast to this film, I contrast Guy Debord’s (1931-1994) contemporaneous film The Society of the Spectacle (1973). As a filmmaker Debord successfully dealt with alienation in film. -

Retrospektive Viennale 1998 CESTERREICHISCHES FILM

Retrospektive Viennale 1998 CESTERREICHISCHES FILM MUSEUM Oktober 1998 RETROSPEKTIVE JEAN-LUC GODARD Das filmische Werk IN ZUSAMMENARBEIT MIT BRITISH FILM INSTITUTE, LONDON • CINEMATHEQUE DE TOULOUSE • LA CINl-MATHfeQUE FRAN^AISE, PARIS • CINIiMATHkQUE MUNICIPALE DE LUXEMBOURG. LUXEMBURG FREUNDE DER DEUTSCHEN KINEMATHEK. BERLIN ■ INSTITUT FRAN^AIS DB VIENNE MINISTERE DES AFFAIRES ETRANGERES, PARIS MÜNCHNER STADTMUSEUM - FILMMUSEUM NATIONAL FILM AND TELEVISION ARCHIVE, LONDON STIFTUNG PRO HEI.VETIA, ZÜRICH ZYKLISCHES PROGRAMM - WAS IST FILM * DIE GESCHICHTE DES FILMISCHEN DENKENS IN BEISPIELEN MIT FILMEN VON STAN BRAKHAGE • EMILE COHL • BRUCE CONNER • WILLIAM KENNEDY LAURIE DfCKSON - ALEKSANDR P DOVSHENKO • MARCEL DUCHAMP • EDISON KINETOGRAPH • VIKING EGGELING; ROBERT J. FLAHERTY ROBERT FRANK • JORIS IVENS • RICHARD LEACOCK • FERNAND LEGER CIN^MATOGRAPHE LUMIERE • ETIENNE-JULES MAREY • JONAS MEKAS • GEORGES MELIUS • MARIE MENKEN • ROBERT NELSON • DON A. PENNEBAKER • MAN RAY • HANS RICHTER • LENI glEFENSTAHL • JACK SMITH • DZIGA VERTOV 60 PROGRAMME • 30 WOCHEN • JÄHRLICH WIEDERHOLT • JEDEN DIENSTAG ZWEI VORSTELLUNGEN Donnerstag, 1. Oktober 1998, 17.00 Uhr Marrfnuß sich den anderen leihen, sich jedoch Monsigny; Darsteller: Jean-Claude Brialy. UNE FEMME MARIEE 1964) Sonntag, 4. Oktober 1998, 19.00 Uhr Undurchsichtigkeit und Venvirrung. Seht, die Rea¬ Mittwoch, 7. Oktober 1998, 21.00 Uhr Raou! Coutard; Schnitt: Agnes Guiliemot; Die beiden vorrangigen Autoren der Gruppe Dziga sich selbst geben- Montaigne Sein Leben leben. Anne Colette, Nicole Berger Regie: Jean-Luc Godard; Drehbuch: Jean-Luc lität. metaphorisiert Godaiti nichtsonderlich inspi¬ Musik: Karl-Heinz Stockhausen, Franz Vertov. Jean-Luc Godard und Jean-Pierre Gönn, CHARLOTTE ET SON JULES (1958) VfVRE SA VIE. Die Heldin, die dies versucht: eine MASCULIN - FEMININ (1966) riert, em Strudel, in dem sich die Wege verlaufen. -

JLG CATALOG-MAIN1.Pdf

Ο Ζαν Λυκ Γκοντάρ είναι κορυφαίος σκηνοθέτης που τα έργα του δεν έπαψαν να μαγνητίζουν το κοινό τα τελευταία πενήντα χρόνια αλλά και ένας διανο- ητής που συγκεντρώνει τον θαυμασμό ιστορικών, θεωρητικών και φιλοσόφων. Πώς εξηγείται αυτή η ακαταμάχητη γοητεία αυτού του τρομερού παιδιού της Νουβέλ Βαγκ; Είναι μήπως η ικανότητα του «να αντιπαραθέτει σε ασαφείς ιδέ- ες καθαρές εικόνες;» Σύμφωνα με την θεωρητικό Κατερίνα Λουκοπούλου: «Ο Γκοντάρ από την αρχή της πορείας του όχι μόνο χρησιμοποίησε λέξεις και εικόνες για να θέσει ερωτή- ματα του τύπου «τί είναι ο κινηματογράφος» αλλά και για να ξανασκεφτεί την πορεία του κινηματογράφου: επιτυγχάνει την αναθεώρηση των κινηματογρα- φικών ειδών, τον αναστοχασμό και την επανεφεύρεση της κινηματογραφικής γλώσσας, με κάθε ταινία του που βγήκε στην διανομή, από το με Κομμένη την Ανάσα (1960) ως το Αποχαιρετισμός στη Γλώσσα (2014), στρέφεται με πάθος σε συλλογικά εγχειρήματα (στην αρχή με την ομάδα Τζίγκα Βερτόφ και αργότερα με την Sonimage και την Αν-Μαρί Μιεβίλ), υπογράφει μεγάλο αριθμό έργων για την τηλεόραση και ολοκληρώνει το εμβληματικό έργο του Ιστορία/ες του Κινηματογράφου. Ο διαλογισμός του Γκοντάρ πάνω στον κινηματογράφο δεν σταματά ποτέ. Έχει γυρίσει ταινίες για το σινεμά, έχει γράψει αναλύσεις, έχει δώσει εμπνευσμένες συνεντεύξεις και έχει κάνει πολλές τηλεοπτικές εμφανί- σεις μιλώντας για τις ταινίες του αλλά και ευρύτερα για τον κινηματογράφο». Η Ταινιοθήκη με τη διοργάνωση του αφιερώματος Τώρα Γκοντάρ με 52 ταινίες, στο πλαίσιο του προγράμματος «Η κινηματογραφοφιλία στη Νέα Εποχή» και με τη συνεργασία του Γαλλικού Ινστιτούτου Ελλάδος και την υποστήριξη της Πρεσβείας της Ελβετίας είναι περήφανη γιατί θα δώσει τη δυνατότητα στους ειδικούς να τον ξαναδούν και στους νέους την ευκαιρία να γνωρίσουν τον με- γάλο εικονοκλάστη. -

GAUMONT PRESENTS: a CENTURY of FRENCH CINEMA, on View Through April 14, Includes Fifty Programs of Films Made from 1900 to the Present

The Museum of Modern Art For Immediate Release January 1994 GAUNONT PRESENTS: A CENTURY OF FRENCH CINEMA January 28 - April 14, 1994 A retrospective tracing the history of French cinema through films produced by Gaumont, the world's oldest movie studio, opens at The Museum of Modern Art on January 28, 1994. GAUMONT PRESENTS: A CENTURY OF FRENCH CINEMA, on view through April 14, includes fifty programs of films made from 1900 to the present. All of the films are recently restored, and new 35mm prints were struck especially for the exhibition. Virtually all of the sound films feature new English subtitles as well. A selection of Gaumont newsreels [actualites) accompany the films made prior to 1942. The exhibition opens with the American premiere of Bertrand Blier's Un deux trois soleil (1993), starring Marcello Mastroianni and Anouk Grinberg, on Friday, January 28, at 7:30 p.m. A major discovery of the series is the work of Alice Guy-Blache, the film industry's first woman producer and director. She began making films as early as 1896, and in 1906 experimented with sound, using popular singers of the day. Her film Sur la Barricade (1906), about the Paris Commune, is featured in the series. Other important directors whose works are included in the exhibition are among Gaumont's earliest filmmakers: the pioneer animator and master of trick photography Emile Cohl; the surreal comic director Jean Durand; the inventive Louis Feuillade, who went on to make such classic serials as Les Vampires (1915) and Judex (1917), both of which are shown in their entirety; and Leonce Perret, an outstanding early realistic narrative filmmaker. -

Jean-Luc Godard – Musicien

Jean-Luc Godard – musicien Jürg Stenzl Stenzl_Godard.indb 1 24.11.10 14:30 Jürg Stenzl, geb. 1942 in Basel, studierte in Bern und Paris, lehrte von 1969 bis 1991 als Musikhistoriker an der Universität Freiburg (Schweiz), von 1992 an in Wien und Graz und hatte seit Herbst 1996 bis 2010 den Lehrstuhl für Mu- sikwissenschaft an der Universität Salzburg inne. Zahlreiche Gastprofessuren, zuletzt 2003 an der Harvard University. Publizierte Bücher und über 150 Auf- sätze zur europäischen Musikgeschichte vom Mittelalter bis in die Gegenwart. Stenzl_Godard.indb 2 24.11.10 14:30 Jean-Luc Godard – musicien Die Musik in den Filmen von Jean-Luc Godard Jürg Stenzl Stenzl_Godard.indb 3 24.11.10 14:30 Gedruckt mit Unterstützung durch das Rektorat der Universität Salzburg, Herrn Rektor Prof. Dr. Heinrich Schmidinger. Bibliografische Information der Deutschen Nationalbibliothek Die Deutsche Nationalbibliothek verzeichnet diese Publikation in der Deutschen Nationalbibliografie; detaillierte bibliografische Daten sind im Internet über http://dnb.d-nb.de abrufbar. ISBN 978-3-86916-097-9 © edition text + kritik im RICHARD BOORBERG VERLAG GmbH & Co KG, München 2010 Levelingstr. 6a, 81673 München www.etk-muenchen.de Das Werk einschließlich aller seiner Teile ist urheberrechtlich geschützt. Jede Verwertung, die nicht ausdrücklich vom Urheberrechtsgesetz zugelassen ist, bedarf der vorherigen Zustim- mung des Verlages. Dies gilt insbesondere für Vervielfältigungen, Bearbeitungen, Übersetzungen, Mikroverfilmungen und die Einspeicherung und Verarbeitung in elektronischen -

22—25 Juin 2017

22—25 juin 2017 TOULOUSE MÉTROPOLE 13e festival international de littérature LE MARATHON DES MOTS SOMMAIRE Direction - Programmation : Serge Roué Direction déléguée : Dalia Hassan Coordination générale : Noémie de La Soujeole assistée de Marion Lemmet Communication : Édouard de Cazes ÉDITOS assisté de Laure Perrinet Service de presse : Shanaz Barday Olivier POIVRE DʼARVOR ........................................ 5 (Faits & Gestes - 01 53 34 64 84) Jean-Luc MOUDENC ............................................... 5 assistée de Camille Carnevale Carole DELGA ......................................................... 7 Évènements spéciaux : Elsa Viguier Coordination des bénévoles : Charlotte Barbe Philippe WAHL ......................................................... 7 assistée de Nelly Frisicaro Serge ROUÉ | Dalia HASSAN .................................. 9 Collaboration artistique : Patrick Autréaux, Laurent Belvèze, Jean-Jacques Cubaynes (Lettres occitanes) et Guillaume Poix Coordination technique : Jean-Pierre Siguier (SED Spectacles) PROGRAMME Jeudi 22 juin ............................................................................................................ 11 TOULOUSE, LE MARATHON DU LIVRE Vendredi 23 juin ................................................................................................. 23 Association Loi 1901 (Siret 481 981 165 000 30 - Code APE : 8230Z Samedi 24 juin ..................................................................................................... 43 Licences n°2-1052821 et n° 3-1052822) Dimanche