Durham E-Theses

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

231 BOOK REVIEWS John Pritchard

Methodist History, 52:4 (July 2014) BOOK REVIEWS John Pritchard, Methodists and Their Mission Societies, 1760-1900. Surrey, England: Ashgate Publishing, 2013. 318 pp. £63. Methodists and Their Mission Societies, 1760-1900, is the first part of a two-volume series by John Pritchard about British Methodist mission work around the world. The publication of this series marks the two hundredth anniversary of the first meeting of the Wesleyan Methodist Missionary Society (WMMS) in October of 1883 in Leeds. Moreover the book updates the 1913 five volume work by G.G. Findlay and W.W. Holdsworth entitled The History of the Wesleyan Methodist Missionary Society (Epworth). The focus of this work is further broadened and includes the mission work of four other denominations (Primitive Methodists, Methodist New Connexion, United Methodist Free Churches and Bible Christians) under the Wesleyan Methodist Missionary Society to become the Methodist Mission Society in 1932. Pritchard records in great detail the early Methodist mission efforts around the world including the roles of John Wesley, Thomas Coke, Jabez Bunting and other mission proponents. Beginning with the backdrop of six- teenth-century Catholic and late seventeenth-century to early eighteenth-cen- tury German Pietist mission work, the book quickly focuses on the British context. The author describes the priority of the Society for the Promotion of the Gospel (SPG) to provide for the spiritual needs of the colonists before evangelizing native peoples. William Caray’s 1792 Enquiry, which led to the creation of the Baptist Missionary Society, and Thomas Coke’s apoca- lyptic urgency heightened this priority, however the tension between empire and mission to the indigenous remained for several decades—varying from country to country. -

Jabez Bunting

JA BEZ B U N T I N G A GREAT METHO DIST LEA DER I D . REV. MES H RR N R G D O G . JA A IS , T HE M D ETHO IST BOO' CON C ERN . N EW 'OR ' C I CI AT I N NN . P R E 'A C E N o o ne can feel more deeply than the writer how inadequate is the little book he h a s i written , when crit cally regarded as a life - sketch of the greatest man o f middle Methodism , to whose gifts and character organized Wesleyan Methodism throughout the world owes incomparably more than to any other man , With more Space a better book might and ought to have been made . But to bring the book within reach of every intelligent and earnest Methodist youth and ’ o f every working man s family , a very cheap volume was necessary , and therefore a very small one . The writer has done his best, w accordingly , to meet the vie s of the Metho dist Publishing House in this matter . He knows how great and serious are some o f the deficiencies in this record ; especially 6 Pre fa ce o n i the side of Methodist Fore gn Missions , hi as to w ch he has said nothing , though Jabez Bunting in this field was the prime and most influential organizer in all the early ’ years of o u r Church s Connexional mission work and world -wide enterprises The subject was too large and wide , too various and too complicated , to be dealt with in a section of a small book . -

Collection on British Wesleyan Conference Presidents

Collection on British Wesleyan Conference Presidents A Guide to the Collection Overview Creator: Bridwell Library Title: Collection on British Wesleyan Conference Presidents Inclusive Dates: 1773-1950 Bulk Dates: 1790-1900 Abstract: Bridwell Library’s collection on British Wesleyan Conference Presidents comprises three scrapbook albums containing printed likenesses, biographical sketches, autographs, correspondence, and other documents relating to every British Wesleyan Conference president who served between 1790 (John Wesley) and 1905 (Charles H. Kelly). The collection represents the convergence of British Victorian interests in Methodistica and scrapbooking. To the original scrapbooks Bishop Frederick DeLand Leete added materials by and about ten additional twentieth-century Conference presidents. Accession No: BridArch 302.26 Extent: 6 boxes (3.5 linear feet) Language: Material is in English Repository Bridwell Library, Perkins School of Theology, Southern Methodist University Historical Note Conference Presidents in the Methodist Church of Great Britain serve one year terms in which they travel throughout Great Britain preaching and representing the denomination. Conference Presidents may serve non-consecutive additional terms. John Wesley personally presided over 1 Bridwell Library * Perkins School of Theology * Southern Methodist University annual conferences of ordained ministers and lay preachers serving in connection with the Methodist movement beginning in 1744. The office of President was instituted after Wesley’s death in 1791. Bridwell Library is the principal bibliographic resource at Southern Methodist University for the fields of theology and religious studies. Source: “The President and Vice-President,” Methodist Church of Great Britain website http://www.methodist.org.uk/who-we-are/structure/the-president-and-vice-president, accessed 07/23/2013 Scope and Contents of the Collection The engraved portraits, biographical notes, autographs, and letters in this collection represent every Conference president who served between 1790 and 1905. -

Introduction Welcome to the Methodist Church Here at High Street

Introduction Welcome to the Methodist Church here at High Street, Maidenhead. We hope that your visit to this long - established and continuously active church will be both be for you an architectural interest and an appreciation of the lives of some of the people associated with it over the past 150 years or so. There has been a Chapel on this site since 1841 which was built for the Countess of Huntingdon’s Connexion. Originally it was a rectangular shape measuring approximately 65 ft x 35 ft. A partition across its width allowed about three quarters of the building at its north end to be used for worship whilst the remainder consisted of two rooms one above the other. A gallery at the northern end (above today’s vestibule) also housed the organ. The foundation stone was laid on 30 March 1841. The property and grounds (about one third of an acre) were purchased by the Methodist Church on 8th October 1858 and redeveloped. Consequently the partition and two rooms were removed and the worship extended to south wall. New pews were added, basic heating installed and the gallery repaired. The normal seating capacity was therefore increased to 400 with space to accommodate 550 “at a push” should circumstances require. A Vestry and Schoolroom were built on the southern end of the site. Since then the church interior has had considerable alteration the most significant of which have been the addition, and subsequent removal, of galleries along the side walls and the addition of the two transepts. The last major refurbishment of the interior took place in 1991 when the whole of the church interior was gutted, the pews removed, the ceiling woodwork grit-blasted, the walls re- plastered, galleries rebuilt, organ re-positioned, floor re-carpeted, new lighting installed and more glass incorporated into the main and side entrances. -

Holiness Works.Pdf

All Rights Reserved By HDM For This Digital Publication Copyright 1996 Holiness Data Ministry Duplication of this CD by any means is forbidden, and copies of individual files must be made in accordance with the restrictions stated in the B4Ucopy.txt file on this CD. * * * * * * * HOLINESS WORKS -- A BIBLIOGRAPHY Compiled And Edited By William Charles Miller A Revised Edition Of The Master Bibliography Of Holiness Works Printed for Nazarene Theological Seminary By Nazarene Publishing House Kansas City, Missouri Copyright 1986 By Nazarene Publishing House ISBN: 083-411-1721 Printed in the United States of America * * * * * * * Digital Edition 10/02/96 By Holiness Data Ministry With Permission From William C. Miller * * * * * * * NOTICE TO USERS OF THIS DIGITAL EDITION OF HOLINESS WORKS: DO NOT MAKE PRINTED COPIES OF THE ENTIRE BIBLIOGRAPHY WITHOUT OBTAINING PERMISSION FROM WILLIAM C. MILLER We appreciate Dr. Miller's generosity in allowing us to create and publish this electronic edition of his very useful Holiness Works Bibliography. In fairness to him, we ask that all users of this electronic publication strictly adhere to the above requirement, employing this bibliography for the glory of God without abusing the privilege. -- Duane V. Maxey, Holiness Data Ministry * * * * * * * INTRODUCTION In 1965 the Master Bibliography of Holiness was prepared by Nazarene Theological Seminary and published by Nazarene Publishing House as an aid to the study of the doctrine of holiness. Rev. Larry Stover, a graduate of Nazarene Theological Seminary, reminded the publishing house of the need for an updated edition of the bibliography when he prepared a bibliography for his own use and then presented it for possible publication. -

CLARKE by J.W.Etheridge 2

THE LIFE OF ADAM CLARKE by J.W.Etheridge 2 THE LIFE of the REV. ADAM CLARKE, LL.D. By J. W. Etheridge Published in 1858 3 CONTENTS ------------------------- [Transcriber Note: The electronic version of the this book has been divided into into 30 consecutive divisions — including the 29 total book chapters and the final supplement. Therefore, the original table of contents has been altered to show these 30 divisions.] INTRODUCTORY BOOK I THE MORNING OF LIFE DIV. 1 — CHAPTER 1 His Parentage and Childhood DIV. 2 — CHAPTER 2 Regenerate DIV. 3 — CHAPTER 3 First Essays in the Service of Christ DIV. 4 — CHAPTER 4 The opened Road rough at the Outset DIV. 5 — CHAPTER 5 The Evangelist DIV. 6 — CHAPTER 6 The Evangelist DIV. 7 — CHAPTER 7 The Missionary DIV. 8 — CHAPTER 8 The Circuit Minister DIV. 9 — CHAPTER 9 The Circuit Minister BOOK II MERIDIAN DIV. 10 — CHAPTER 1 The Preacher DIV. 11 — CHAPTER 2 The Pastor DIV. 12 — CHAPTER 3 The Preacher and Pastor — continued DIV. 13 — CHAPTER 4 The Preacher and Pastor — continued DIV. 14 — CHAPTER 5 The President DIV. 15 — CHAPTER 6 Itinerancy DIV. 16 — CHAPTER 7 Itinerancy DIV. 17 — CHAPTER 8 The Student and Scholar 4 DIV. 18 — CHAPTER 9 The Student — continued DIV. 19 — CHAPTER 10 The Author DIV. 20 — CHAPTER 11 The Literary Servant of the State DIV. 21 — CHAPTER 12 The Coadjutor of the Bible Society DIV. 22 — CHAPTER 13 The Commentator BOOK III EVENING DIV. 23 — CHAPTER 1 The Elder revered in the Church DIV. 24 — CHAPTER 2 Honoured by the Great and Good DIV. -

125 BOOK REVIEW J. Russell Frazier

Methodist History, 53:2 (January 2015) BOOK REVIEW J. Russell Frazier, True Christianity, The Doctrine of Dispensations in the Thought of John William Fletcher (1729-1785). Eugene, OR: Pickwick Publications, 2014. 320 pp. $31.50. J. Russell Frazier has offered a comprehensive interpretation of John William Fletcher’s doctrine of dispensations. He appropriately entitled it, True Christianity. Frazier has provided the context for understanding the thought of John Fletcher, highlighting that in his mature theological understanding he developed a soteriology corresponding to the history of salvation. Fletcher shows that the development of God’s revelation as Father, Son, and Holy Spirit generally reflects the personal history of salvation. In this reckoning, each individual believer progressively transitions from a general awareness of God to a more specific knowledge of God as Father and Creator revealed in the Old Testament. The believer then progresses to the knowledge of Jesus Christ, whose life is distinguished between his earthly ministry entailing his life, death, and resurrection (Easter) and the outpouring of his Holy Spirit upon the church (Pentecost). Frazier shows that the most problematic feature of Fletcher’s theology of dispensations is the soteriological use that he made between the early followers of Jesus (pre-Pentecostal believers) and Pentecostal believers. This theology of dispensations, as Frazier so rightly pointed out, has nothing in common with the dispensational theology of Darby or Schofield. As Frazier showed, Fletcher understood Jesus’ earthly life as a brief period of time which represented a development of faith which was “singular” (as Fletcher put it) to John the Baptist and the early disciples of Jesus. -

Jabez Bunting

8 EARLY CORRESPONDENCE OF JABEZ BUNTING In 1826 the Leeds circuit was divided, and there was great ill-feeling over the division of the Sunday school, which was not in origin a circuit or even a Methodist institution, and from the radical leaders of which serious trouble was expected. The explosion in fact came over the proposal to install an organ in the Brunswick chapel which was new, fashionable, and reputed the largest in the connexion. The law was clear that the organ might be introduced only with Conference consent after an investigation and approval by a District Meeting, and clear on almost nothing else. The Brunswick Trustees applied for the organ by a majority of 8 votes to 6 with one neutral; the Leaders' Meeting, viewing the organ as a middle-class status symbol, and thoroughly irritated by the new arrangements in the circuit and by the itinerants' refusal to entertain any representations from the local preachers, opposed it by a majority of more than twenty to one, and were upheld by the District Meeting. Bunting nevertheless persuaded a Conference committee largely composed of the same preachers who had met in the District Meeting to reverse their ver- dict. When serious opposition developed in Leeds, Conference sovereignty was demonstrated by the summoning of a Special District Meeting (attended by Bunting as President's special adviser) to settle the affairs of the circuit. This court expelled members in large numbers without trial before a Leaders' Meeting from which palatable verdicts could not have been obtained. This exercise of central authority and personal influence turned the radicals into inveterate defenders of circuit rights, led in 1828 to the formation of a secession connexion, the Leeds Protestant Methodists, and estab- lished their view of Bunting as the Methodist Pope. -

THE JOURNAL of the UNITED REFORMED CHURCH HISTORY

THE JOURNAL of the UNITED REFORMED CHURCH HISTORY SOCIETY (incorporating the Congregational Historical Society, founded in 1899, and the Presbyterian Historical Society of England founded in 1913.) . EDITOR; Dr. CLYDE BINFIELD, M.A., F.S.A. Volume 5 No.8 May 1996 CONTENTS Editorial and Notes .......................................... 438 Gordon Esslemont by Stephen Orchard, M.A., Ph.D. 439 The Origins of the Missionary Society by Stephen Orchard, M.A., Ph.D . ........................... 440 Manliness and Mission: Frank Lenwood and the London Missionary Society by Brian Stanley, M.A., Ph.D . .............................. 458 Training for Hoxton and Highbury: Walter Scott of Rothwell and his Pupils by Geoffrey F. Nuttall, F.B.A., M.A., D.D. ................... 477 Mr. Seymour and Dr. Reynolds by Edwin Welch, M.A., Ph.D., F.S.A. ....................... 483 The Presbyterians in Liverpool. Part 3: A Survey 1900-1918 by Alberta Jean Doodson, M.A., Ph.D . ....................... 489 Review Article: Only Connect by Stephen Orchard, M.A., Ph.D. 495 Review Article: Mission and Ecclesiology? Some Gales of Change by Brian Stanley, M.A., Ph.D . .............................. 499 Short Reviews by Daniel Jenkins and David M. Thompson 503 Some Contemporaries by Alan P.F. Sell, M.A., B.D., Ph.D . ......................... 505 437 438 EDITORIAL There is a story that when Mrs. Walter Peppercorn gave birth to her eldest child her brother expressed the hope that the little peppercorn would never get into a piclde. This so infuriated Mr. Peppercorn that he changed their name to Lenwood: or so his wife's family liked to believe. They were prosperous Sheffielders whom he greatly surprised by leaving a considerable fortune; he had proved to be their equal in business. -

Catalogue from Selecat

GENERAL AND REFERENCE 13 ) Osborn, G.; OUTLINES OF WESLEYAN BIBLIOGRAPHY OR A RECORD OF METHODIST 1 ) ; THE FIRST ANNUAL REPORT OF THE WESLEYAN LITERATURE FROM THE BEGINNING IN TWO PARTS; CHAPEL COMMITTEE 1855 [BOUND WITH] THE WCO; 1869; Osborn, G.Osborn, G. 220pp; Hardback, purple SECOND 1856 THE THIRD 1857 THE FOURTH 1858 cloth, spine faded & nicked. (M12441) £40 THE FIFTH 1859 THE SIXTH 1860 THE SEVENTH ANNUAL REPORT 1861; Hayman Brothers; 1855; pp; 14 ) Relly, James; UNION OR A TREATISE OF THE Rebound in black quarter leather. 7 parts bound together. Some CONSANGUINITY AND AFFINITY BETWEEN CHRIST dampstaining, mainly to the 3rd report. Illustrated with AND HIS CHURCH [WITH] THE SADDUCEE DETECTED lithographs. (M12201) £75 AND REFUTED IN REMARKS ON THE WORKS OF RICHARD COPPIN [1764]; Printed in the year; 1759; Relly, 2 ) ; THE METHODIST WHO'S WHO 1912; Charles H. JamesRelly, James 138+94+94pp; Full calf, gilt. Red leather Kelly; 1912; 255pp; Hardback, red cloth. (M12318) spine labels. Also bound in "The Trial of Spirits" 1762 without £20 title page. 3 works bound together, all rare. (M11994) 3 ) Batty, Margaret; STAGES IN THE DEVELOPMENT £100 AND CONTROL OF WESLEYAN LAY LEADERSHIP 1791- 15 ) Sangster, W.E.; METHODISM CAN BE BORN AGAIN; 1878; MPH; 1988; Batty, MargaretBatty, Margaret 275pp; Hodder & Stoughton; 1938; Sangster, W.E.Sangster, W.E. Paperback, covers dusty. Ring bound. (M12629) £10 128pp; Paperback. (M12490) £3 4 ) Cadogan, Claude L.; METHODISM: ITS IMPACT ON 16 ) Skewes, John Henry; A COMPLETE AND POPULAR CARIBBEAN PEOPLE A BICENTENNIAL LECTURE; St. DIGEST OF THE POLITY OF METHODISM EACH George's Grenada; 1986; Cadogan, Claude L.Cadogan, Claude SUBJECT ALPHABETICALLY ARRANGED; Elliot Stock; L. -

John Wesley's Eucharist and the Online Eucharist

John Wesley’s Eucharist and the Online Eucharist By KIOH SHIM A thesis submitted to The University of Birmingham for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of Theology and Religion College of Arts and Law The University of Birmingham March 2013 University of Birmingham Research Archive e-theses repository This unpublished thesis/dissertation is copyright of the author and/or third parties. The intellectual property rights of the author or third parties in respect of this work are as defined by The Copyright Designs and Patents Act 1988 or as modified by any successor legislation. Any use made of information contained in this thesis/dissertation must be in accordance with that legislation and must be properly acknowledged. Further distribution or reproduction in any format is prohibited without the permission of the copyright holder. Abstract Since the late 20th century information technology has changed the lives of individuals and relationships at local, nation and even global levels. In particular the internet is used by many religious groups for theological and spiritual purposes. Some parts of Christianity have confronted the issue of how to deal with the use of internet. As a result, an internet church has emerged, offering Eucharistic services online across the globe. Even though the numbers of internet churches/Eucharistic groups have sharply increased in the last two decades, the attitude of the established churches does not appear to have taken account of this change yet. To achieve this it is necessary for such initiatives to be guided by certain theological norms or church regulations. This may relate to the definition of church, Eucharistic theology, or how to deal with emerging cultures. -

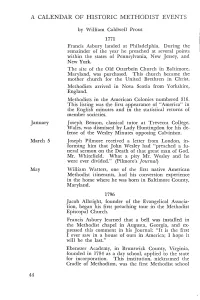

}\ Calendar of Historic Methodist Events

}\ CALENDAR OF HISTORIC METHODIST EVENTS by \IVilliam Caldwell Prout 1771 Francis Asbury landed at Philadelphia. During the remainder of the year he preached at several points within the states of Pennsylvania, New Jersey, and New York. The site of the Old Otterbein Church in Baltimore, Maryland, was purchased. This church became the mother church for the United Brethren in Christ. Methodists arrived in Nova Scotia from Yorkshire, England. Methodists in the American Colonies numbered 316. This listing was the first appearance of "America" in the English minutes and in the statistical returns of member societies. January Joseph Benson, classical tutor at Trevecca Col~ege, Wales, was dismissed by Lady Huntingdon for his de fense of the Wesley Minutes opposing Calvinism. March 5 Joseph Pilmore received a letter from London, in forming him that John Wesley had "preached a fu neral sermon on the Death of that great 11lan of God, Mr. Whitefield. What a pity Mr. '!\Tesley and he were ever divided." (Pilmore's ] oUTnal) May William Watters, one of the first native American Methodist itinerants, had his conversion experienc~ in the home where he was born in Baltimore County, Maryland. 1796 Jacob Albright, founder of the Evangelical Associa tion, began his first preaching tour in the Methodist Episcopal Church. Francis Asbury learned that a bell was installed in the Methodist chapel in Augusta, Georgia, and ex pressed this comment in his Journal: "It is the first I ever sa,,y in a house of ours in America; I hope it will be the last." Ebenezer Academy, in Brunswick County, Virginia, founded in 1784 as a day school, applied to the state for incorporation.