Everywhere but Antarctica: Using a Super Tree to Understand the Diversity and Distribution of the Compositae

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

BOG SNEEZEWEED Scientific Name: Helenium Brevifolium (Nuttall)

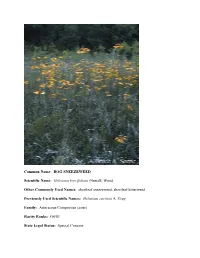

Common Name: BOG SNEEZEWEED Scientific Name: Helenium brevifolium (Nuttall) Wood Other Commonly Used Names: shortleaf sneezeweed, shortleaf bitterweed Previously Used Scientific Names: Helenium curtissii A. Gray Family: Asteraceae/Compositae (aster) Rarity Ranks: G4/S1 State Legal Status: Special Concern Federal Legal Status: none Federal Wetland Status: OBL Description: Perennial herb with winged, purple stems, 1 - 2½ feet (30 - 80 cm) tall, hairless except the top of the stem, which is covered with cottony hairs. Basal leaves ¾ - 6¾ inches (2 - 17 cm) long and ¼ - 1 inch (0.6 - 3 cm) wide, purple-tinged, spatula-shaped, mostly hairless, present during flowering. Stem leaves smaller, few and widely spaced, alternate, with cottony hairs on both surfaces; leaf bases extend well down along the stem, forming narrow wings. Flower heads 1 - 10 per plant, with 8 - 24 yellow ray flowers, each ray with 3 or 5 teeth, and many reddish-brown disk flowers. Fruit dry and seed-like, with bristles. Similar Species: Spring sneezeweed (Helenium vernale) has one flower head per plant and yellow disk flowers; its stems and leaves are hairless; its basal leaves are up to 10 inches long and much longer than wide. Southeastern sneezeweed (H. pinnatifidum) leaves barely extend down along the stem; flower stalks are rough-hairy; and it has 13 - 40 ray flowers crowded around a yellow disk. Southern sneezeweed (H. flexuosum) usually has many heads in a branched cluster; its disk flowers are purple with 4 lobes. Related Rare Species: None in Georgia. Habitat: Pine- or cypress-dominated wet savannas, seepage slopes, bogs, boggy stream banks, Atlantic white cedar swamps, and powerlines or other clearings through these habitats. -

Diabetes and Medicinal Plants: a Literature Review

ISOLATION AND IDENTIFICATION OF ANTIDIABETIC COMPOUNDS FROM BRACHYLAENA DISCOLOR DC Thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree Master of Science By Sabeen Abdalbagi Elameen Adam School of Chemistry and Physics University of KwaZulu-Natal Pietermaritzburg Supervisor: Professor Fanie R. van Heerden August 2017 ABSTRACT Diabetes mellitus, which is a metabolic disease resulting from insulin deficiency or diminished effectiveness of the action of insulin or their combination, is recognized as a major threat to human life. Using drugs on a long term to control glucose can increase the hazards of cardiovascular disease and some cancers. Therefore, there is an urgent need to discover new, safe, and effective antidiabetic drugs. Traditionally, there are several plants that are used to treat/control diabetes by South African traditional healers such as Brachylaena discolor. This study aimed to isolate and identify antidiabetic compounds from B. discolor. The plant materials of B. discolor was collected from University of KwaZulu-Natal botanical garden. Plant materials were dried under the fume hood for two weeks and ground to a fine powder. The powder was extracted with a mixture of dichloromethane and methanol (1:1). To investigate the antidiabetic activity, the prepared extract was tested in vitro for glucose utilization in a muscle cell line. The results revealed that blood glucose levels greater than 20 mmol/L, which measured after 24 and 48 hours of the experimental period, three fractions had positive (*p<0.05) antidiabetic activity compared to the control. The DCM:MeOH (1:1) extract of B. discolor leaves was subjected to column chromatography, yielding five fractions (A, B, C, D, and E). -

Southwest Guangdong, 28 April to 7 May 1998

Report of Rapid Biodiversity Assessments at Qixingkeng Nature Reserve, Southwest Guangdong, 29 April to 1 May and 24 November to 1 December, 1998 Kadoorie Farm and Botanic Garden in collaboration with Guangdong Provincial Forestry Department South China Institute of Botany South China Agricultural University South China Normal University Xinyang Teachers’ College January 2002 South China Biodiversity Survey Report Series: No. 4 (Online Simplified Version) Report of Rapid Biodiversity Assessments at Qixingkeng Nature Reserve, Southwest Guangdong, 29 April to 1 May and 24 November to 1 December, 1998 Editors John R. Fellowes, Michael W.N. Lau, Billy C.H. Hau, Ng Sai-Chit and Bosco P.L. Chan Contributors Kadoorie Farm and Botanic Garden: Bosco P.L. Chan (BC) Lawrence K.C. Chau (LC) John R. Fellowes (JRF) Billy C.H. Hau (BH) Michael W.N. Lau (ML) Lee Kwok Shing (LKS) Ng Sai-Chit (NSC) Graham T. Reels (GTR) Gloria L.P. Siu (GS) South China Institute of Botany: Chen Binghui (CBH) Deng Yunfei (DYF) Wang Ruijiang (WRJ) South China Agricultural University: Xiao Mianyuan (XMY) South China Normal University: Chen Xianglin (CXL) Li Zhenchang (LZC) Xinyang Teachers’ College: Li Hongjing (LHJ) Voluntary consultants: Guillaume de Rougemont (GDR) Keith Wilson (KW) Background The present report details the findings of two field trips in Southwest Guangdong by members of Kadoorie Farm & Botanic Garden (KFBG) in Hong Kong and their colleagues, as part of KFBG's South China Biodiversity Conservation Programme. The overall aim of the programme is to minimise the loss of forest biodiversity in the region, and the emphasis in the first three years is on gathering up-to-date information on the distribution and status of fauna and flora. -

Brachylaena Elliptica and B. Ilicifolia (Asteraceae): a Comparative Analysis of Their Ethnomedicinal Uses, Phytochemistry and Biological Activities

Journal of Pharmacy and Nutrition Sciences, 2020, 10, 223-229 223 Brachylaena elliptica and B. ilicifolia (Asteraceae): A Comparative Analysis of their Ethnomedicinal Uses, Phytochemistry and Biological Activities Alfred Maroyi* Department of Botany, University of Fort Hare, Private Bag X1314, Alice 5700, South Africa Abstract: Brachylaena elliptica and B. ilicifolia are shrubs or small trees widely used as traditional medicines in southern Africa. There is need to evaluate the existence of any correlation between the medicinal uses, phytochemistry and pharmacological properties of the two species. Therefore, in this review, analyses of the ethnomedicinal uses, phytochemistry and biological activities of B. elliptica and B. ilicifolia are presented. Results of the current study are based on data derived from several online databases such as Scopus, Google Scholar, PubMed and Science Direct, and pre-electronic sources such as scientific publications, books, dissertations, book chapters and journal articles. The articles published between 1941 and 2020 were used in this study. The leaves and roots of B. elliptica and B. ilicifolia are mainly used as a mouthwash and ethnoveterinary medicines, and traditional medicines for backache, hysteria, ulcers of the mouth, diabetes, gastro-intestinal and respiratory problems. This study showed that sesquiterpene lactones, alkaloids, essential oils, flavonoids, flavonols, phenols, proanthocyanidins, saponins and tannins have been identified from aerial parts and leaves of B. elliptica and B. ilicifolia. The leaf extracts and compounds isolated from the species exhibited antibacterial, antidiabetic, antioxidant and cytotoxicity activities. There is a need for extensive phytochemical, pharmacological and toxicological studies of crude extracts and compounds isolated from B. elliptica and B. ilicifolia. -

Occasional Papers from the Lindley Library © 2011

Occasional Papers from The RHS Lindley Library IBRARY L INDLEY L , RHS VOLUME FIVE MARCH 2011 Eighteenth-century Science in the Garden Cover illustration: Hill, Vegetable System, vol. 23 (1773) plate 20: Flower-de-luces, or Irises. Left, Iris tuberosa; right, Iris xiphium. Occasional Papers from the RHS Lindley Library Editor: Dr Brent Elliott Production & layout: Richard Sanford Printed copies are distributed to libraries and institutions with an interest in horticulture. Volumes are also available on the RHS website (www. rhs.org.uk/occasionalpapers). Requests for further information may be sent to the Editor at the address (Vincent Square) below, or by email ([email protected]). Access and consultation arrangements for works listed in this volume The RHS Lindley Library is the world’s leading horticultural library. The majority of the Library’s holdings are open access. However, our rarer items, including many mentioned throughout this volume, are fragile and cannot take frequent handling. The works listed here should be requested in writing, in advance, to check their availability for consultation. Items may be unavailable for various reasons, so readers should make prior appointments to consult materials from the art, rare books, archive, research and ephemera collections. It is the Library’s policy to provide or create surrogates for consultation wherever possible. We are actively seeking fundraising in support of our ongoing surrogacy, preservation and conservation programmes. For further information, or to request an appointment, please contact: RHS Lindley Library, London RHS Lindley Library, Wisley 80 Vincent Square RHS Garden Wisley London SW1P 2PE Woking GU23 6QB T: 020 7821 3050 T: 01483 212428 E: [email protected] E : [email protected] Occasional Papers from The RHS Lindley Library Volume 5, March 2011 B. -

27April12acquatic Plants

International Plant Protection Convention Protecting the world’s plant resources from pests 01 2012 ENG Aquatic plants their uses and risks Implementation Review and Support System Support and Review Implementation A review of the global status of aquatic plants Aquatic plants their uses and risks A review of the global status of aquatic plants Ryan M. Wersal, Ph.D. & John D. Madsen, Ph.D. i The designations employed and the presentation of material in this information product do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO) concerning the legal or development status of any country, territory, city or area or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. The mention of speciic companies or products of manufacturers, whether or not these have been patented, does not imply that these have been endorsed or recommended by FAO in preference to others of a similar nature that are not mentioned.All rights reserved. FAO encourages reproduction and dissemination of material in this information product. Non-commercial uses will be authorized free of charge, upon request. Reproduction for resale or other commercial purposes, including educational purposes, may incur fees. Applications for permission to reproduce or disseminate FAO copyright materials, and all queries concerning rights and licences, should be addressed by e-mail to [email protected] or to the Chief, Publishing Policy and Support Branch, Ofice of Knowledge Exchange, -

Appendix 1: Maps and Plans Appendix184 Map 1: Conservation Categories for the Nominated Property

Appendix 1: Maps and Plans Appendix184 Map 1: Conservation Categories for the Nominated Property. Los Alerces National Park, Argentina 185 Map 2: Andean-North Patagonian Biosphere Reserve: Context for the Nominated Proprty. Los Alerces National Park, Argentina 186 Map 3: Vegetation of the Valdivian Ecoregion 187 Map 4: Vegetation Communities in Los Alerces National Park 188 Map 5: Strict Nature and Wildlife Reserve 189 Map 6: Usage Zoning, Los Alerces National Park 190 Map 7: Human Settlements and Infrastructure 191 Appendix 2: Species Lists Ap9n192 Appendix 2.1 List of Plant Species Recorded at PNLA 193 Appendix 2.2: List of Animal Species: Mammals 212 Appendix 2.3: List of Animal Species: Birds 214 Appendix 2.4: List of Animal Species: Reptiles 219 Appendix 2.5: List of Animal Species: Amphibians 220 Appendix 2.6: List of Animal Species: Fish 221 Appendix 2.7: List of Animal Species and Threat Status 222 Appendix 3: Law No. 19,292 Append228 Appendix 4: PNLA Management Plan Approval and Contents Appendi242 Appendix 5: Participative Process for Writing the Nomination Form Appendi252 Synthesis 252 Management Plan UpdateWorkshop 253 Annex A: Interview Guide 256 Annex B: Meetings and Interviews Held 257 Annex C: Self-Administered Survey 261 Annex D: ExternalWorkshop Participants 262 Annex E: Promotional Leaflet 264 Annex F: Interview Results Summary 267 Annex G: Survey Results Summary 272 Annex H: Esquel Declaration of Interest 274 Annex I: Trevelin Declaration of Interest 276 Annex J: Chubut Tourism Secretariat Declaration of Interest 278 -

V. Munnozia Ortiziae (Liabeae), a New Species from the Andes of Pasco, Peru

Pruski, J.F. 2012. Studies of Neotropical Compositae–V. Munnozia ortiziae (Liabeae), a new species from the Andes of Pasco, Peru. Phytoneuron 2012-2: 1–6. Published 1 January 2012. ISSN 2153 733X STUDIES OF NEOTROPICAL COMPOSITAE–V. MUNNOZIA ORTIZIAE (LIABEAE), A NEW SPECIES FROM THE ANDES OF PASCO, PERU JOHN F. PRUSKI Missouri Botanical Garden P.O. Box 299 St. Louis, Missouri 63166 ABSTRACT A new species, Munnozia ortiziae Pruski (Compositae: Liabeae: Munnoziinae), is described from the Andes of Pasco, Peru. It is most similiar to M. oxyphylla , also of Peru, in its pinnately veined, lanceolate to elliptic-lanceolate leaves and moderately large capitula in loose, open cymose capitulescences. KEY WORDS: Andes, Asteraceae, Compositae, Liabeae, Liabum , Munnozia , Munnoziinae, Pasco, Peru. Munnozia Ruiz & Pav. (Compositae: Liabeae: Munnoziinae) is an Andean-centered genus of more than 40 species (Robinson 1978, 1983). It was resurrected from synonymy of Liabum Adans. by Robinson and Brettell (1974) and differs from Liabum by black (vs. pale) anther thecae. A new species, Munnozia ortiziae Pruski, from the Andes of Pasco, Peru, is described herein. The new species appears most similar to M. oxyphylla (Cuatrec.) H. Rob., which is known from Huánuco and Pasco, Peru. MUNNOZIA ORTIZIAE Pruski, sp. nov. TYPE : PERU. Pasco. Prov. Oxapampa. Dist. Oxapampa: La Suiza Nueva, open forest with many tree ferns, 10°38' S, 75°27' W, 2240 m, 21 Jun 2003, H. van der Werff, R. Vásquez, B. Gray, R. Rojas, R. Ortiz , & N. Davila 17600 (holotype: MO; isotypes: AMAZ, F, HOXA, USM). Figures 1–5. Plantae herbaceae perennes vel fruticosae usque ca. -

APPENDIX a Plant Species List of Boschhoek Mountain Estate Trees

APPENDIX A Plant species list of Boschhoek Mountain Estate Trees 52 Shrubs 36 Dwarf shrubs 25 Forbs 81 Grasses 78 Geophytes 4 Succulents 6 Parasites 7 Sedges 9 Ferns 5 Aliens 19 Total 322 Trees Acacia burkei swartapiesdoring black monkey-thorn Acacia caffra gewone haakdoring common hook-thorn Acacia karroo soetdoring sweet thorn Acacia robusta enkeldoring, brakdoring ankle thorn, brack thorn Albizia tanganyicensis papierbasvalsdoring paperbark false thorn Berchemia zeyheri rooi-ivoor red ivory Brachylaena rotundata bergvaalbos mountain silver oak Burkea africana wilde sering, rooisering wild seringa, red syringa Celtisa africana witstinkhout white stinkwood Combretum apiculatum rooibos red bushwillow Combretum molle fluweelboswilg velvet bushwillow Combretum zeyheri raasblaar large-fruited bushwillow Commiphora mollis fluweelkanniedood velvet corkwood Croton gratissimus laventelkoorsbessie lavender fever-berry Cussonia paniculata Hoëveldse kiepersol Highveld cabbage tree Cussonia spicata gewone kiepersol common cabbage tree Cussonia transvaalensis Transvaalse kiepersol Transvaal cabbage tree Diplorrhynchus condylocarpum horingpeulbos horn-pod tree Dombeya rotundifolia drolpeer, wilde peer wild pear Dovyalis caffra Keiappel Kei-apple Dovyalis zeyheri wilde-appelkoos wild apricot Englerophytum magalismontanum stamvrug Transvaal milkplum Erythrina lysistemon gewone koraalboom common coral tree Euclea crispa blougwarrie blue ghwarri Faurea saligna Transvaalboekenhout Transvaal beech 93 Ficus abutilifolia grootblaarrotsvy large-leaved rock -

Bio 308-Course Guide

COURSE GUIDE BIO 308 BIOGEOGRAPHY Course Team Dr. Kelechi L. Njoku (Course Developer/Writer) Professor A. Adebanjo (Programme Leader)- NOUN Abiodun E. Adams (Course Coordinator)-NOUN NATIONAL OPEN UNIVERSITY OF NIGERIA BIO 308 COURSE GUIDE National Open University of Nigeria Headquarters 14/16 Ahmadu Bello Way Victoria Island Lagos Abuja Office No. 5 Dar es Salaam Street Off Aminu Kano Crescent Wuse II, Abuja e-mail: [email protected] URL: www.nou.edu.ng Published by National Open University of Nigeria Printed 2013 ISBN: 978-058-434-X All Rights Reserved Printed by: ii BIO 308 COURSE GUIDE CONTENTS PAGE Introduction ……………………………………......................... iv What you will Learn from this Course …………………............ iv Course Aims ……………………………………………............ iv Course Objectives …………………………………………....... iv Working through this Course …………………………….......... v Course Materials ………………………………………….......... v Study Units ………………………………………………......... v Textbooks and References ………………………………........... vi Assessment ……………………………………………….......... vi End of Course Examination and Grading..................................... vi Course Marking Scheme................................................................ vii Presentation Schedule.................................................................... vii Tutor-Marked Assignment ……………………………….......... vii Tutors and Tutorials....................................................................... viii iii BIO 308 COURSE GUIDE INTRODUCTION BIO 308: Biogeography is a one-semester, 2 credit- hour course in Biology. It is a 300 level, second semester undergraduate course offered to students admitted in the School of Science and Technology, School of Education who are offering Biology or related programmes. The course guide tells you briefly what the course is all about, what course materials you will be using and how you can work your way through these materials. It gives you some guidance on your Tutor- Marked Assignments. There are Self-Assessment Exercises within the body of a unit and/or at the end of each unit. -

Standardization of the Plant Epaltes Pygmaea DC. (Asteraceae)

K. Amala et al. / Journal of Pharmacy Research 2016,10(10),674-682 Research Article Available online through ISSN: 0974-6943 http://jprsolutions.info Standardization of the plant Epaltes pygmaea DC. (Asteraceae) K. Amala*1 , R. Ilavarasan2, S. Amerjothy3 1,2Captain Srinivasa Murti Regional Ayurveda Drug Development Institute (CCRAS), Anna Hospital Campus, Arumbakkam, Chennai –600 106, India. 2Department of Plant Biology & Plant Biotechnology, Presidency College, Chennai. India. Received on:17-09-2016; Revised on: 22-10-2016; Accepted on: 03-11-2016 ABSTRACT Background: To establish the pharmacognostic parameters using pharmacopoeial standards for correct identity of whole plant of Epaltes pygmaea DC. (Asteraceae). Methods: In pharmacognostic studies different types of evaluations were carried out that focus on taxonomy of the species, macro- and microscopic characters, physico-chemical parameters, fluorescence analysis, preliminary phytochemical screening and HPTLC finger print compared with marker compound stigmosterol. Results and discussion: The taxonomically it is a small annual herb, 8 to 20 cm high, minutely winged branched stem with aromatic roots, leaves are alternate, linear, lanceolate to oblong, flower pink, solitary, terminal, heterogamous. Microscopically the plant showed the presence of bi or tri-radiate wings of the stem, leaves microscopy indicated the presence of anisocytic type of stomata, thin walled with small spindle shaped cells of leaf epidermis, powder microscopy showed vessel elements with short tail, vertical chain of elongated parenchyma cells with prominent simple pits, large, spherical and spiny pollen grains. Plant extracts showed the presence of flavonoids, steroids, phenols, tannin and sugars. The standard marker stigmosterol detected with Rf 0.54 in alcohol extract has been confirmed by TLC/HPTLC finger print. -

Host Plants of Cuscuta Glomerata

Proceedings of the Iowa Academy of Science Volume 42 Annual Issue Article 8 1935 Host Plants of Cuscuta glomerata H. L. Dean State University of Iowa Let us know how access to this document benefits ouy Copyright ©1935 Iowa Academy of Science, Inc. Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.uni.edu/pias Recommended Citation Dean, H. L. (1935) "Host Plants of Cuscuta glomerata," Proceedings of the Iowa Academy of Science, 42(1), 45-47. Available at: https://scholarworks.uni.edu/pias/vol42/iss1/8 This Research is brought to you for free and open access by the Iowa Academy of Science at UNI ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Proceedings of the Iowa Academy of Science by an authorized editor of UNI ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Dean: Host Plants of Cuscuta glomerata HOST PLAXTS OF CUSCUTA GLOMERATA H. L. DEAN In a previous paper ( 1934) the writer listed eighty-three species of host plants of Cuscuta Gronoi·ii \Villd. for West Virginia. Later six additional hosts for this species were added, as a result of greenhouse experiments at the State University of Iowa, making a total of eighty-nine host plants observed by the writer for this species. During field studies and greenhouse experiments involving Cuscuta glomcrata Choisy a considerable number of host plants has been listed for this species of dodder. Due to the number and variety of these hosts, and since no list of specific host plants has been published for this species, the appended list should be of interest.