Occasional Papers from the Lindley Library © 2011

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

BOG SNEEZEWEED Scientific Name: Helenium Brevifolium (Nuttall)

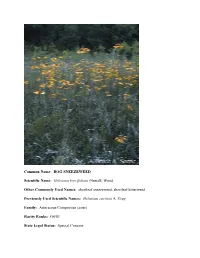

Common Name: BOG SNEEZEWEED Scientific Name: Helenium brevifolium (Nuttall) Wood Other Commonly Used Names: shortleaf sneezeweed, shortleaf bitterweed Previously Used Scientific Names: Helenium curtissii A. Gray Family: Asteraceae/Compositae (aster) Rarity Ranks: G4/S1 State Legal Status: Special Concern Federal Legal Status: none Federal Wetland Status: OBL Description: Perennial herb with winged, purple stems, 1 - 2½ feet (30 - 80 cm) tall, hairless except the top of the stem, which is covered with cottony hairs. Basal leaves ¾ - 6¾ inches (2 - 17 cm) long and ¼ - 1 inch (0.6 - 3 cm) wide, purple-tinged, spatula-shaped, mostly hairless, present during flowering. Stem leaves smaller, few and widely spaced, alternate, with cottony hairs on both surfaces; leaf bases extend well down along the stem, forming narrow wings. Flower heads 1 - 10 per plant, with 8 - 24 yellow ray flowers, each ray with 3 or 5 teeth, and many reddish-brown disk flowers. Fruit dry and seed-like, with bristles. Similar Species: Spring sneezeweed (Helenium vernale) has one flower head per plant and yellow disk flowers; its stems and leaves are hairless; its basal leaves are up to 10 inches long and much longer than wide. Southeastern sneezeweed (H. pinnatifidum) leaves barely extend down along the stem; flower stalks are rough-hairy; and it has 13 - 40 ray flowers crowded around a yellow disk. Southern sneezeweed (H. flexuosum) usually has many heads in a branched cluster; its disk flowers are purple with 4 lobes. Related Rare Species: None in Georgia. Habitat: Pine- or cypress-dominated wet savannas, seepage slopes, bogs, boggy stream banks, Atlantic white cedar swamps, and powerlines or other clearings through these habitats. -

Richard Bradley's Illicit Excursion Into Medical Practice in 1714

CORE Metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk Provided by PubMed Central RICHARD BRADLEY'S ILLICIT EXCURSION INTO MEDICAL PRACTICE IN 1714 by FRANK N. EGERTON III* INTRODUCTION The development of professional ethics, standards, practices, and safeguards for the physician in relation to society is as continuous a process as is the development of medicine itself. The Hippocratic Oath attests to the antiquity of the physician's concern for a responsible code of conduct, as the Hammurabi Code equally attests to the antiquity of society's demand that physicians bear the responsibility of reliable practice." The issues involved in medical ethics and standards will never be fully resolved as long as either medicine or society continue to change, and there is no prospect of either becoming static. Two contemporary illustrations will show the on-going nature of the problems of medical ethics. The first is a question currently receiving international attention and publicity: what safeguards are necessary before a person is declared dead enough for his organs to be transplanted into a living patient? The other illustration does not presently, as far as I know, arouse much concern among physicians: that medical students carry out some aspects of medical practice on charity wards without the patients being informed that these men are as yet still students. Both illustrations indicate, I think, that medical ethics and standards should be judged within their context. If and when a consensus is reached on the criteria of absolute death, the ethical dilemma will certainly be reduced, if not entirely resolved. If and when there is a favourable physician-patient ratio throughout the world and the economics of medical care cease to be a serious problem, then the relationship of medical students to charity patients may become subject to new consideration. -

G - S C/44/5 ORIGINAL: English/Français/Deutsch/Español DATE/DATUM/FECHA: 2010-10-20

E - F - G - S C/44/5 ORIGINAL: English/français/deutsch/español DATE/DATUM/FECHA: 2010-10-20 INTERNATIONAL UNION UNION INTERNATIONALE INTERNATIONALER UNIÓN INTERNACIONAL FOR THE PROTECTION POUR LA PROTECTION VERBAND ZUM SCHUTZ PARA LA PROTECCIÓN OF NEW VARIETIES DES OBTENTIONS VON PFLANZEN DE LAS OBTENCIONES OF PLANTS VÉGÉTALES ZÜCHTUNGEN VEGETALES GENEVA GENÈVE GENF GINEBRA COUNCIL CONSEIL DER RAT CONSEJO Forty-Fourth Quarante-quatrième Vierundvierzigste Cuadragésima cuarta Ordinary Session session ordinaire ordentliche Tagung sesión ordinaria Geneva, October 21, 2010 Genève, 21 octobre 2010 Genf, 21. Oktober 2010 Ginebra, 21 de octubre de 2010 COOPERATION IN EXAMINATION / COOPÉRATION EN MATIÈRE D’EXAMEN / ZUSAMMENARBEIT BEI DER PRÜFUNG / COOPERACIÓN EN MATERIA DE EXAMEN Document prepared by the Office of the Union / Document établi par le Bureau de l’Union / Vom Verbandsbüro ausgearbeitetes Dokument / Documento preparado por la Oficina de la Unión This document contains a synopsis of offers for cooperation in examination made by authorities, of cooperation already established between authorities and of any envisaged cooperation. * * * * * Le présent document contient un tableau synoptique des offres de coopération en matière d’examen faites par les services compétents, de la coopération déjà établie entre des services et de la coopération prévue. * * * * * Dieses Dokument enthält einen Überblick über Angebote für eine Zusammenarbeit bei der Prüfung, die von Behörden abgegeben worden sind, über Fälle einer bereits verwirklichten Zusammenarbeit zwischen Behörden und über Fälle, in denen eine solche Zusammenarbeit beabsichtigt ist. * * * * * Este documento contiene un cuadro sinóptico de las ofertas de cooperación en materia de examen realizadas por las autoridades, de la cooperación ya establecida entre autoridades y de cualquier otra cooperación prevista. -

'The Publishers of the 1723 Book of Constitutions', AQC 121 (2008)

The Publishers of the 1723 Book of Constitutions Andrew Prescott he advertisements in the issue of the London newspaper, The Evening Post, for 23 February 1723 were mostly for recently published books, including a new edition of the celebrated directory originally compiled by John Chamberlayne, Magnae Britanniae Notitia, and books offering a new cure for scurvy and advice Tfor those with consumption. Among the advertisements for new books in The Evening Post of 23 February 1723 was the following: This Day is publiſh’d, † || § The CONSTITUTIONS of the FREE- MASONS, containing the Hiſtory, Charges, Regulations, &c., of that moſt Ancient and Right Worſhipful Fraternity, for the Uſe of the Lodges. Dedicated to his Grace the Duke of Montagu the laſt Grand Maſter, by Order of his Grace the Duke of Wharton, the preſent Grand Maſter, Authoriz’d by the Grand Lodge of Maſters and War- dens at the Quarterly Communication. Ordered to be publiſh’d and recommended to the Brethren by the Grand Maſter and his Deputy. Printed for J. Senex, and J. Hooke, both over againſt St Dunſtan’s Church, Fleet-ſtreet. An advertisement in similar terms, also stating that the Constitutions had been pub- lished ‘that day’, appeared in The Post Boy of 26 February, 5 March and 12 March 1723 Volume 121, 2008 147 Andrew J. Prescott and TheLondon Journal of 9 March and 16 March 1723. The advertisement (modified to ‘just publish’d’) continued to appear in The London Journal until 13 April 1723. The publication of The Constitutions of the Free-Masons, or the Book of Constitutions as it has become generally known, was a fundamental event in the development of Grand Lodge Freemasonry, and the book remains an indispensable source for the investigation of the growth of Freemasonry in the first half of the eighteenth century. -

The Botany of Empire in the Long Eighteenth Century Yota Batsaki Dumbarton Oaks

University of Dayton eCommons Marian Library Faculty Publications The aM rian Library 2017 The Botany of Empire in the Long Eighteenth Century Yota Batsaki Dumbarton Oaks Sarah Burke Cahalan University of Dayton, [email protected] Anatole Tchikine Dumbarton Oaks Follow this and additional works at: https://ecommons.udayton.edu/imri_faculty_publications eCommons Citation Batsaki, Yota; Cahalan, Sarah Burke; and Tchikine, Anatole, "The Botany of Empire in the Long Eighteenth Century" (2017). Marian Library Faculty Publications. Paper 28. https://ecommons.udayton.edu/imri_faculty_publications/28 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the The aM rian Library at eCommons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Marian Library Faculty Publications by an authorized administrator of eCommons. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. The Botany of Empire in the Long Eighteenth Century YOTA BATSAKI SARAH BURKE CAHALAN ANATOLE TCHIKINE Dumbarton Oaks Research Library and Collection Washington, D.C. © 2016 Dumbarton Oaks Trustees for Harvard University, Washington, D.C. All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Names: Batsaki, Yota, editor. | Cahalan, Sarah Burke, editor. | Tchikine, Anatole, editor. Title: The botany of empire in the long eighteenth century / Yota Batsaki, Sarah Burke Cahalan, and Anatole Tchikine, editors. Description: Washington, D.C. : Dumbarton Oaks Research Library and Collection, [2016] | Series: Dumbarton Oaks symposia and colloquia | Based on papers presented at the symposium “The Botany of Empire in the Long Eighteenth Century,” held at Dumbarton Oaks, Washington, D.C., on October 4–5, 2013. | Includes bibliographical references and index. -

2004 Cultivar Trials of Bedding Plants

2004 Cultivar Trials of Bedding Plants Barbara A. Laschkewitsch, M.S. Trial Garden Coordinator Ronald C. Smith, Ph.D. Extension Horticulturist – Department of Plant Sciences Introduction The Plant Sciences Department at NDSU conducted performance trials on over 300 annual bedding plants during the 2004 growing season. The main research garden is located in Fargo, on the west edge of campus. Trial gardens are also located at the research extension centers in Dickinson and Williston, ND. Official entries (usually 150-200) are grown at all three locations while an additional 150-200 cultivars are also grown at the Fargo site. The display gardens are for educational and research purposes. They are open to the public throughout the growing season and guided tours are available upon request. The trial garden is an official display garden of both All-America Selections and the American Hemerocallis Society. Currently, there are over 1100 cultivars of daylilies in the collection with plans for more. The majority of the daylily cultivars are considered historic (pre-1970). There are also over 300 miscellaneous perennials and ornamental grasses in the garden. An extensive iris collection, courtesy of the Art Jensen family, was also added in 2003. New Fargo trial gardens are currently being constructed on the corner of 18th street and 12th avenue north. The move into the new beds should be completed by fall 2005. Culture Plants were seeded in the horticulture and forestry greenhouses on the NDSU campus from January through April, 2004. When at the proper stage, seedlings were transplanted into cell packs containing a peat-based growing medium. -

The British Journal for the History of Science Mechanical Experiments As Moral Exercise in the Education of George

The British Journal for the History of Science http://journals.cambridge.org/BJH Additional services for The British Journal for the History of Science: Email alerts: Click here Subscriptions: Click here Commercial reprints: Click here Terms of use : Click here Mechanical experiments as moral exercise in the education of George III FLORENCE GRANT The British Journal for the History of Science / Volume 48 / Issue 02 / June 2015, pp 195 - 212 DOI: 10.1017/S0007087414000582, Published online: 01 August 2014 Link to this article: http://journals.cambridge.org/abstract_S0007087414000582 How to cite this article: FLORENCE GRANT (2015). Mechanical experiments as moral exercise in the education of George III. The British Journal for the History of Science, 48, pp 195-212 doi:10.1017/ S0007087414000582 Request Permissions : Click here Downloaded from http://journals.cambridge.org/BJH, IP address: 130.132.173.207 on 07 Jul 2015 BJHS 48(2): 195–212, June 2015. © British Society for the History of Science 2014 doi:10.1017/S0007087414000582 First published online 1 August 2014 Mechanical experiments as moral exercise in the education of George III FLORENCE GRANT* Abstract. In 1761, George III commissioned a large group of philosophical instruments from the London instrument-maker George Adams. The purchase sprang from a complex plan of moral education devised for Prince George in the late 1750s by the third Earl of Bute. Bute’s plan applied the philosophy of Frances Hutcheson, who placed ‘the culture of the heart’ at the foundation of moral education. To complement this affective development, Bute also acted on seventeenth-century arguments for the value of experimental philosophy and geometry as exercises that habituated the student to recognizing truth, and to pursuing it through long and difficult chains of reasoning. -

Host Plants of Cuscuta Glomerata

Proceedings of the Iowa Academy of Science Volume 42 Annual Issue Article 8 1935 Host Plants of Cuscuta glomerata H. L. Dean State University of Iowa Let us know how access to this document benefits ouy Copyright ©1935 Iowa Academy of Science, Inc. Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.uni.edu/pias Recommended Citation Dean, H. L. (1935) "Host Plants of Cuscuta glomerata," Proceedings of the Iowa Academy of Science, 42(1), 45-47. Available at: https://scholarworks.uni.edu/pias/vol42/iss1/8 This Research is brought to you for free and open access by the Iowa Academy of Science at UNI ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Proceedings of the Iowa Academy of Science by an authorized editor of UNI ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Dean: Host Plants of Cuscuta glomerata HOST PLAXTS OF CUSCUTA GLOMERATA H. L. DEAN In a previous paper ( 1934) the writer listed eighty-three species of host plants of Cuscuta Gronoi·ii \Villd. for West Virginia. Later six additional hosts for this species were added, as a result of greenhouse experiments at the State University of Iowa, making a total of eighty-nine host plants observed by the writer for this species. During field studies and greenhouse experiments involving Cuscuta glomcrata Choisy a considerable number of host plants has been listed for this species of dodder. Due to the number and variety of these hosts, and since no list of specific host plants has been published for this species, the appended list should be of interest. -

Redeeming the Truth

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA Los Angeles Redeeming the Truth: Robert Morden and the Marketing of Authority in Early World Atlases A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy in History by Laura Suzanne York 2013 © Copyright by Laura Suzanne York 2013 ABSTRACT OF THE DISSERTATION Redeeming the Truth: Robert Morden and the Marketing of Authority in Early World Atlases by Laura Suzanne York Doctor of Philosophy in History University of California, Los Angeles, 2013 Professor Muriel C. McClendon, Chair By its very nature as a “book of the world”—a product simultaneously artistic and intellectual—the world atlas of the seventeenth century promoted a totalizing global view designed to inform, educate, and delight readers by describing the entire world through science and imagination, mathematics and wonder. Yet early modern atlas makers faced two important challenges to commercial success. First, there were many similar products available from competitors at home and abroad. Secondly, they faced consumer skepticism about the authority of any work claiming to describe the entire world, in the period before standards of publishing credibility were established, and before the transition from trust in premodern geographic authorities to trust in modern authorities was complete. ii This study argues that commercial world atlas compilers of London and Paris strove to meet these challenges through marketing strategies of authorial self-presentation designed to promote their authority to create a trustworthy world atlas. It identifies and examines several key personas that, deployed through atlas texts and portraits, together formed a self-presentation asserting the atlas producer’s cultural authority. -

Accd Nuclear Transfer of Platycodon Grandiflorum and the Plastid of Early

Hong et al. BMC Genomics (2017) 18:607 DOI 10.1186/s12864-017-4014-x RESEARCH ARTICLE Open Access accD nuclear transfer of Platycodon grandiflorum and the plastid of early Campanulaceae Chang Pyo Hong1, Jihye Park2, Yi Lee3, Minjee Lee2, Sin Gi Park1, Yurry Uhm4, Jungho Lee2* and Chang-Kug Kim5* Abstract Background: Campanulaceae species are known to have highly rearranged plastid genomes lacking the acetyl-CoA carboxylase (ACC) subunit D gene (accD), and instead have a nuclear (nr)-accD. Plastid genome information has been thought to depend on studies concerning Trachelium caeruleum and genome announcements for Adenophora remotiflora, Campanula takesimana, and Hanabusaya asiatica. RNA editing information for plastid genes is currently unavailable for Campanulaceae. To understand plastid genome evolution in Campanulaceae, we have sequenced and characterized the chloroplast (cp) genome and nr-accD of Platycodon grandiflorum, a basal member of Campanulaceae. Results: We sequenced the 171,818 bp cp genome containing a 79,061 bp large single-copy (LSC) region, a 42,433 bp inverted repeat (IR) and a 7840 bp small single-copy (SSC) region, which represents the cp genome with the largest IR among species of Campanulaceae. The genome contains 110 genes and 18 introns, comprising 77 protein-coding genes, four RNA genes, 29 tRNA genes, 17 group II introns, and one group I intron. RNA editing of genes was detected in 18 sites of 14 protein-coding genes. Platycodon has an IR containing a 3′ rps12 operon, which occurs in the middle of the LSC region in four other species of Campanulaceae (T. caeruleum, A. remotiflora, C. -

Hunt, Stephen E. "'Free, Bold, Joyous': the Love of Seaweed in Margaret Gatty and Other Mid–Victorian Writers." Environment and History 11, No

The White Horse Press Full citation: Hunt, Stephen E. "'Free, Bold, Joyous': The Love of Seaweed in Margaret Gatty and Other Mid–Victorian Writers." Environment and History 11, no. 1 (February 2005): 5–34. http://www.environmentandsociety.org/node/3221. Rights: All rights reserved. © The White Horse Press 2005. Except for the quotation of short passages for the purpose of criticism or review, no part of this article may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical or other means, including photocopying or recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without permission from the publishers. For further information please see http://www.whpress.co.uk. ʻFree, Bold, Joyousʼ: The Love of Seaweed in Margaret Gatty and Other Mid-Victorian Writers STEPHEN E. HUNT Wesley House, 10 Milton Park, Redfield, Bristol, BS5 9HQ Email: [email protected] ABSTRACT With particular reference to Gattyʼs British Sea-Weeds and Eliotʼs ʻRecollections of Ilfracombeʼ, this article takes an ecocritical approach to popular writings about seaweed, thus illustrating the broader perception of the natural world in mid-Victorian literature. This is a discursive exploration of the way that the enthusiasm for seaweed reveals prevailing ideas about propriety, philanthropy and natural theology during the Victorian era, incorporating social history, gender issues and natural history in an interdisciplinary manner. Although unchaperoned wandering upon remote shorelines remained a questionable activity for women, ʻseaweedingʼ made for a direct aesthetic engagement with the specificity of place in a way that conforms to Barbara Gatesʼs notion of the ʻVictorian female sublimeʼ. -

Everywhere but Antarctica: Using a Super Tree to Understand the Diversity and Distribution of the Compositae

BS 55 343 Everywhere but Antarctica: Using a super tree to understand the diversity and distribution of the Compositae VICKI A. FUNK, RANDALL J. BAYER, STERLING KEELEY, RAYMUND CHAN, LINDA WATSON, BIRGIT GEMEINHOLZER, EDWARD SCHILLING, JOSE L. PANERO, BRUCE G. BALDWIN, NURIA GARCIA-JACAS, ALFONSO SUSANNA AND ROBERT K. JANSEN FUNK, VA., BAYER, R.J., KEELEY, S., CHAN, R., WATSON, L, GEMEINHOLZER, B., SCHILLING, E., PANERO, J.L., BALDWIN, B.G., GARCIA-JACAS, N., SUSANNA, A. &JANSEN, R.K 2005. Everywhere but Antarctica: Using a supertree to understand the diversity and distribution of the Compositae. Biol. Skr. 55: 343-374. ISSN 0366-3612. ISBN 87-7304-304-4. One of every 10 flowering plant species is in the family Compositae. With ca. 24,000-30,000 species in 1600-1700 genera and a distribution that is global except for Antarctica, it is the most diverse of all plant families. Although clearly mouophyletic, there is a great deal of diversity among the members: habit varies from annual and perennial herbs to shrubs, vines, or trees, and species grow in nearly every type of habitat from lowland forests to the high alpine fell fields, though they are most common in open areas. Some are well-known weeds, but most species have restricted distributions, and members of this family are often important components of 'at risk' habitats as in the Cape Floral Kingdom or the Hawaiian Islands. The sub-familial classification and ideas about major patterns of evolution and diversification within the family remained largely unchanged from Beutham through Cronquist. Recently obtained data, both morphologi- cal and molecular, have allowed us to examine the distribution and evolution of the family in a way that was never before possible.