Identity in Context

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Mass Squash News Massachusetts Squash Newsletter President’S Letter

www.ma-squash.org Winter 2010 Mass Squash News Massachusetts Squash Newsletter President’s Letter This is the most active time of the year for squash. The leagues are at the mid-point, several junior events occurred over the holidays, the high school and college seasons are underway, and the annual state skill level and age group tourneys are about to start. I hope you are getting out there to play! In addition to bringing you the latest on the various squash fronts, this newsletter gives special attention to the many good things happening for junior squash in Massachusetts. We are particularly proud of these programs, which have shown substantial growth in both program offerings and members. The 16-member, all-volunteer MA Squash Junior Committee, led by Tom Poor, is a driving force for much of this success. The Committee has run/will be running 8 sanctioned tournaments this season, several at the national level. A schedule of the tourneys this past/upcoming season on our website can give you an idea of how much high-level competitive squash is available to our juniors. The Junior Committee also runs two free Junior League round robin programs, one for beginner-to-intermediate players, and one for high school players. The round robins are run on weekends at the Harvard Murr Center and Dana Hall Shipley Center courts respectively, and are frequently oversubscribed due to their popularity with both the players and their parents. Thanks to Azi Djazani and the Junior League volunteers for making this program such a great success. -

BOSTON, MA DECEMBER 14-17 Half an Inch Between You and History

2019 BOSTON, MA DECEMBER 14-17 Half an inch between you and history. PRESENTED BY Happening this week. Get tickets at WorldTeamSquashDC.com On behalf of US Squash, welcome to Boston and the 2019 U.S. Junior Open Squash Championships. The U.S. Junior Open is the largest individual squash tournament in the world, but what makes it special is the diverse group of athletes representing over forty countries who will compete this week. Through the competition, players will build new friendships and show that squash’s core values of fair-play, courtesy and respect are universal. We are grateful to the four world-class institutions who have opened their facilities to this championship: Harvard University, MIT, Phillips Academy Andover and Northeastern University. We also appreciate the support of the sponsors, patrons, staff, coaches, volunteers and officials for their commitment to this championship. To the competitors: thank you for showcasing your outstanding skill and sportsmanship at this championship. Please enjoy the event to the fullest – we look to this showcase of junior squash at its very best. Sincerely, Kevin D. Klipstein President & CEO EVENT SCHEDULE Trinity-PawlingBoarding and Day for Boys GradesSchool 7-12 / PG FRIDAY, DECEMBER 13 12:00-7:00pm Registration open at Harvard Murr Center 12:00-9:00pm Practice courts available at Harvard Campus PREVIEW DAY JANUARY 25, 2020 SATURDAY, DECEMBER 14 REGISTER TODAY AT 7:00am Registration opens at Harvard Murr Center www.trinitypawling.org/previewday 7:00am Lunch pickup open at Harvard for players at MIT & or call 845-855-4825 Northeastern 8:00am Matches commence at Harvard, MIT, and Northeastern 10:30am College Recruitment Info Session at the Harvard Murr Lounge (3rd floor) 11:00am Lunch opens at Harvard for participants onsite – ongoing pickup for MIT and Northeastern players 12:30pm College Recruitment Info Session at the Harvard Murr Lounge (3rd floor) 2:00pm Lunch Ends GREATNESS LIVES IN YOU. -

2015-2016 Annual Report Squashbusters’ Mission Is to Challenge and Nurture Urban Youth — As Students, Athletes

2015-2016 ANNUAL REPORT SQUASHBUSTERS’ MISSION IS TO CHALLENGE AND NURTURE URBAN YOUTH — AS STUDENTS, ATHLETES AND CITIZENS — SO THAT THEY To our SQB family, RECOGNIZE AND FULFILL THEIR For many years, squash has kept my family and me fit, taught FULLEST POTENTIAL IN LIFE. us grit and perseverance, and connected us to a network of wonderful people through practice and competitive play. I’ve always known the sport’s potential to do the same for others, SQUASHBUSTERS WAS FOUNDED and since joining the SquashBusters Board in 2008, the program’s incredible impact on its students and their families IN 1996 AS THE COUNTRY’S FIRST has been even greater than I imagined. Over the past 20 URBAN SQUASH AND EDUCATION years, SQB students have consistently graduated high school and matriculated to college at a dramatically higher rate than PROGRAM. ITS PIONEERS WERE 24 their peers, with 99% of program graduates enrolling in college and 78% graduating within six years. In 2015-2016, MIDDLE SCHOOL STUDENTS FROM we continued this success and celebrated a growing program, CAMBRIDGE AND BOSTON. new partnerships, and record-setting events. In 2015-2016, SquashBusters served more young people from Boston and Lawrence than ever before, ending the year with over 200 middle and high school students across both cities. While our tried and true program in Boston has held steady, changing the lives of students from 7th through 12th grade, John, right, with two other loyal friends of SQB: our program in Lawrence continues to grow, one grade at Thierry Lincou, center and Andy Goldfarb, left a time. -

2018 Audited Financial Statements

SQUASHBUSTERS, INC. FINANCIAL STATEMENTS YEAR ENDED JUNE 30, 2018 SQUASHBUSTERS, INC. TABLE OF CONTENTS YEAR ENDED JUNE 30, 2018 Page Independent Auditor’s Report 1 - 2 Financial Statements Statement of Financial Position 3 Statement of Activities and Changes in Net Assets 4 Statement of Functional Expenses 5 Statement of Cash Flows 6 Notes to Financial Statements 7 - 15 Supplementary Information Statements of Activities for the Years Ended June 30, 2018 and 2017 16 Board of Directors Squashbusters, Inc. 795 Columbus Avenue Roxbury Crossing, MA 02120-2108 Re: Independent Auditor’s Report Ladies and Gentlemen: We have audited the accompanying financial statements of Squashbusters, Inc. (a Massachusetts nonprofit organization), which comprise the statement of financial position as of June 30, 2018, and the related statement of activities and changes in net assets, cash flow, and functional expenses for the year then ended, and the related notes to the financial statements. Management’s Responsibility for the Financial Statements Management is responsible for the preparation and fair presentation of these financial statements in accordance with accounting principles generally accepted in the United States of America; this includes the design, implementation, and maintenance of internal control relevant to the preparation and fair presentation of financial statements that are free from material misstatement, whether due to fraud or error. Auditor’s Responsibility Our responsibility is to express an opinion on these financial statements based on our audit. We conducted our audit in accordance with auditing standards generally accepted in the United States of America. Those standards require that we plan and perform the audits to obtain reasonable assurance about whether the financial statements are free of material misstatement. -

Community Resource Manual 2017

Merrimack Valley Community Resource Manual 2017 CHILDREN’S LAW CENTER OF MASSACHUSETTS YOUTH AT RISK A Salem State University Community Program About this Manual This manual is intended to be used as a guide to the many organizations that serve low-income youth and families in the Essex County parts of Merrimack Valley, which include the towns of Amesbury, Andover, Boxford, Georgetown, Groveland, Haverhill, Ipswich, Lawrence, Merrimac, Methuen, Newbury, Newburyport, North Andover, Rowley, Salisbury, Topsfield, and West Newbury. Please note that even if an agency or program serves outside this geographic area, only these cities/towns are listed to conserve space. In the first section, providers are grouped by the type of services they offer. Because some organizations are listed more than once, all details about an organization, including all offices that serve Merrimack Valley, will appear in the first entry. Successive entries will contain only the name of the provider; relevant phone number or website, office information, and services; and the page number on which the complete details of the organization can be found. New in this Merrimack Valley edition, we have added an index. Check it out! We apologize for any omissions of, or mistakes relative to, the names of and/or information about organizations. We will endeavor to correct those omissions/mistakes in future editions. In this edition, we have included only programs and services to which a family may self-refer. We hope to expand to all programs/services in future editions. Feel free to e-mail us at [email protected] or contact us by telephone or by mail with changes, additions, or deletions. -

Education Is Big Business in New England

NNeeww EEnnggllaanndd AAfftteerr 33PPMM Afterschool Alliance 1616 H Street, NW, Suite 820 Washington, DC 20006 www.afterschoolalliance.org Acknowledgements The Afterschool Alliance would like to thank the Nellie Mae Education Foundation for their generous support of this report and for supporting afterschool across the New England Region. We would also like to thank the Statewide Afterschool Networks – Connecticut Afterschool Network, Maine Afterschool Network, Massachusetts Afterschool Partnership, Plus Time New Hampshire, Rhode Island After School Plus Alliance, and Vermont Out-of-School Time – for their contributions to the report and for the important work that they are doing to help afterschool programs thrive in each of the New England states. Executive Summary Some 20 percent of children in New England have no safe, supervised activities after the school day ends each afternoon. These children are in self-care, missing out on opportunities to learn and explore new interests, and at risk for any number of dangerous behaviors including substance abuse, crime and teen pregnancy. Policy makers, parents and many other New Englanders recognize that children, families and communities benefit from quality afterschool programs. They know that an unsupervised child is a child at risk, and they want all the region’s children to have a safe place to go that offers homework help, engaging activities and much more each afternoon. New England is fortunate to have many strong afterschool programs that keep children safe, inspire them to learn and help working families. Some are groundbreaking models that will contribute to the design and structure of afterschool programs serving children and youth nationwide. -

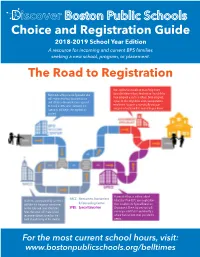

Choice and Registration Guide 2018-2019 School Year Edition a Resource for Incoming and Current BPS Families Seeking a New School, Program, Or Placement

Choice and Registration Guide 2018-2019 School Year Edition A resource for incoming and current BPS families seeking a new school, program, or placement. The Road to Registration Your application travels on to an Assignment Meet with a Registration Specialist who Specialist where it has a final review. Your child is will review residency documentation then assigned a seat in a school. Once assigned, and all other documentation required if your child is eligible for a bus, transportation to enroll in BPS; once reviewed, the enrollment happens automatically and your Specialist will begin the registration assignment notice will be mailed to your home. process. If your child has an Individualized NACC: Newcomers Assessment Students, accompanied by parent(s), Education Plan (IEP), your application will take the language assessment & Counseling Center then travels to the Special Education on the date and time scheduled. SPED: Special Education Department. There, trained staff will After, the tester will make school review your child’s IEP and identify a recommendations based on the school that can best serve your child’s level of proficiency of the student. needs. For the most current school hours, visit: www.bostonpublicschools.org/belltimes IntroductionTitle IMPORTANT DATES Start of End of Priority Priority Assignment Registration Registration Notifications Students January February March entering grades K0, K1, 6, 7, or 9. 3 9 30 February March May Students in all OTHER grades. 12 23 31 oston Public Schools offer academic, social-emotional, cultural, and extracurricular programs that meet the diverse needs of all families across the city. From pre-kindergarten through Bmiddle school and continuing through high school, our schools strive to develop in every learner the knowledge, skills, and character to excel in college, career, and life. -

Education Is Big Business in New England

NNeeww EEnnggllaanndd AAfftteerr 33PPMM Afterschool Alliance 1616 H Street, NW, Suite 820 Washington, DC 20006 www.afterschoolalliance.org Acknowledgements The Afterschool Alliance would like to thank the Nellie Mae Education Foundation for their generous support of this report and for supporting afterschool across the New England Region. We would also like to thank the Statewide Afterschool Networks – Connecticut Afterschool Network, Maine Afterschool Network, Massachusetts Afterschool Partnership, Plus Time New Hampshire, Rhode Island After School Plus Alliance, and Vermont Out-of-School Time – for their contributions to the report and for the important work that they are doing to help afterschool programs thrive in each of the New England states. Executive Summary Some 20 percent of children in New England have no safe, supervised activities after the school day ends each afternoon. These children are in self-care, missing out on opportunities to learn and explore new interests, and at risk for any number of dangerous behaviors including substance abuse, crime and teen pregnancy. Policy makers, parents and many other New Englanders recognize that children, families and communities benefit from quality afterschool programs. They know that an unsupervised child is a child at risk, and they want all the region’s children to have a safe place to go that offers homework help, engaging activities and much more each afternoon. New England is fortunate to have many strong afterschool programs that keep children safe, inspire them to learn and help working families. Some are groundbreaking models that will contribute to the design and structure of afterschool programs serving children and youth nationwide. -

Juniors in Boston for Tournaments

MSRANewww.ma-squash.orgMSRANewsws Spring 2004 MSRANeMSRANeMASSACHUSETTSMSRANe SQUASH RACQUETS ASSOCIATIONwswsws NEWSLETTER PRESIDENT’S LETTER This marks the beginning of my sec- Juniors in Boston for Tournaments ond term as president of the MSRA (and First Annual Urban Youth Squash Team Nationals Held in Boston at SquashBusters without any help from the Supreme Court, I am pleased to say). Looking back over April 17 and 18, 2004 marked the first Annual Urban Youth Squash Team Nation- the last year, I am struck first by how als, hosted at the brand new Badger and Rosen SquashBusters Center at Northeastern quickly it passed. It seems like only yester- University. The event brought together more than 100 middle school and high school day that patient and beleaguered MSRANews editor Sarah Lemaire was aged squash players from five dif- nudging me to submit my first president’s ferent urban squash programs from letter (perhaps because it was only yes- four different cities that together terday that she was nudging me to get my copy in for this one). are changing the perception of Assessing the year, although I am not squash and the lives of hundreds a doctor nor do I even play one on TV, I of urban youth along the East would like to think I fulfilled Hippocrates’s Coast. dictum “at least to do no harm.” (Appar- ently expressed somewhere other than in SquashBusters in Boston; the Hippocratic Oath, as popularly believed, e.g., by me until I looked it up; but I digress.) StreetSquash and CitySquash from This is a recipe for success because the -

2017 Audited Financial Statements

SQUASHBUSTERS, INC. FINANCIAL STATEMENTS TEN MONTHS ENDED JUNE 30, 2017 SQUASHBUSTERS, INC. TABLE OF CONTENTS TEN MONTHS ENDED JUNE 30, 2017 Page Independent Auditor’s Report 1 Financial Statements Statement of Financial Position 2 Statement of Activities and Changes in Net Assets 3 Statement of Functional Expenses 4 Statement of Cash Flows 5 Notes to Financial Statements 6 - 14 Supplementary Information Statements of Activities for the Twelve Months Ended June 30, 2017 and 2016 15 Board of Directors Squashbusters, Inc. 795 Columbus Avenue Roxbury Crossing, MA 02120-2108 Re: Independent Auditor’s Report Ladies and Gentlemen: Report on Financial Statements We have audited the accompanying financial statements of Squashbusters, Inc. (a Massachusetts nonprofit organization), which comprise the statement of financial position as of June 30, 2017, and the related statement of activities and changes in net assets, cash flow, and functional expenses for the period then ended, and the related notes to the financial statements. Management’s Responsibility for the Financial Statements Management is responsible for the preparation and fair presentation of these financial statements in accordance with accounting principles generally accepted in the United States of America; this includes the design, implementation, and maintenance of internal control relevant to the preparation and fair presentation of financial statements that are free from material misstatement, whether due to fraud or error. Auditor’s Responsibility Our responsibility is to express an opinion on these financial statements based on our audits. We conducted our audits in accordance with auditing standards generally accepted in the United States of America. Those standards require that we plan and perform the audits to obtain reasonable assurance about whether the financial statements are free of material misstatement. -

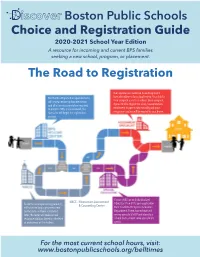

Choice and Registration Guide 2020-2021 School Year Edition a Resource for Incoming and Current BPS Families Seeking a New School, Program, Or Placement

Boston Public Schools Choice and Registration Guide 2020-2021 School Year Edition A resource for incoming and current BPS families seeking a new school, program, or placement. The Road to Registration Your application travels on to an Assignment Meet with a Registration Specialist who Specialist where it has a final review. Your child is will review residency documentation then assigned a seat in a school. Once assigned, and all other documentation required if your child is eligible for a bus, transportation to enroll in BPS; once reviewed, the enrollment happens automatically and your Specialist will begin the registration assignment notice will be mailed to your home. process. If your child has an Individualized NACC: Newcomers Assessment Students, accompanied by parent(s), Education Plan (IEP), your application & Counseling Center will take the language assessment then travels to the Special Education on the date and time scheduled. Department. There, trained staff will After, the tester will make school review your child’s IEP and identify a recommendations based on the level school that can best serve your child’s of proficiency of the student. needs. For the most current school hours, visit: www.bostonpublicschools.org/belltimes Introduction IMPORTANT DATES Start of End of Priority Priority Assignment Registration Registration Notifications Students January January March entering grades K0, K1, 6, 7, or 9. 6 31 31 Students February April May entering K2 & ALL OTHER grades. 10 3 29 oston Public Schools offer academic, social-emotional, cultural, and extracurricular programs that meet the diverse needs of all families across the city. From pre- Bkindergarten through high school, our schools strive to develop in every learner the knowledge, skills, and character to excel in college, career, and life. -

NUSEA International Affiliation Membership Application.Docx

Urban Squash Citizenship Tour Boston, Connecticut, Jersey Shore, Philadelphia, Washington, DC July 15-23 Citizenship Tour For 22 high school and college squash players from Harlem, Roxbury, South Chicago, and similar communities throughout the United States, the Urban Squash Citizenship Tour will be a 9-day athletic and intellectual journey from Boston to Washington, DC with stops in Connecticut, New York City, the Jersey Shore, and Philadelphia. The students, who have been selected from the country’s 15 urban squash programs, will play squash, visit landmarks of American history, and meet with individuals in government, journalism, education and the nonprofit community. Among other highlights, students will meet UN Ambassador Samantha Power, Representative John Lewis of Georgia, and Environmental Defense Fund CEO Fredd Krupp. They will also play squash with Governor of Massachusetts Deval Patrick in Boston and Senator Kirsten Gillibrand of New York in Washington, DC. The group will visit Walden Pond, sleep in dorms at Harvard University, walk the Freedom Trail in Boston, and tour the United Nations and New York Times Building in New York City and the U.S. Capitol and the White House in Washington, DC. Squash Squash was founded in the 1860s at the Harrow School, a private boarding school in England. Twenty years later the first court was built in the United States at the St. Paul’s School in Concord, New Hampshire. The game is played in 180 countries by more than 10 million people, and the countries where it is most popular include England, Australia, Malaysia, and Egypt. For most of its history in the United States, the sport has been played primarily at independent schools, Northeastern universities, and private clubs.