Education Is Big Business in New England

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Mass Squash News Massachusetts Squash Newsletter President’S Letter

www.ma-squash.org Winter 2010 Mass Squash News Massachusetts Squash Newsletter President’s Letter This is the most active time of the year for squash. The leagues are at the mid-point, several junior events occurred over the holidays, the high school and college seasons are underway, and the annual state skill level and age group tourneys are about to start. I hope you are getting out there to play! In addition to bringing you the latest on the various squash fronts, this newsletter gives special attention to the many good things happening for junior squash in Massachusetts. We are particularly proud of these programs, which have shown substantial growth in both program offerings and members. The 16-member, all-volunteer MA Squash Junior Committee, led by Tom Poor, is a driving force for much of this success. The Committee has run/will be running 8 sanctioned tournaments this season, several at the national level. A schedule of the tourneys this past/upcoming season on our website can give you an idea of how much high-level competitive squash is available to our juniors. The Junior Committee also runs two free Junior League round robin programs, one for beginner-to-intermediate players, and one for high school players. The round robins are run on weekends at the Harvard Murr Center and Dana Hall Shipley Center courts respectively, and are frequently oversubscribed due to their popularity with both the players and their parents. Thanks to Azi Djazani and the Junior League volunteers for making this program such a great success. -

BOSTON, MA DECEMBER 14-17 Half an Inch Between You and History

2019 BOSTON, MA DECEMBER 14-17 Half an inch between you and history. PRESENTED BY Happening this week. Get tickets at WorldTeamSquashDC.com On behalf of US Squash, welcome to Boston and the 2019 U.S. Junior Open Squash Championships. The U.S. Junior Open is the largest individual squash tournament in the world, but what makes it special is the diverse group of athletes representing over forty countries who will compete this week. Through the competition, players will build new friendships and show that squash’s core values of fair-play, courtesy and respect are universal. We are grateful to the four world-class institutions who have opened their facilities to this championship: Harvard University, MIT, Phillips Academy Andover and Northeastern University. We also appreciate the support of the sponsors, patrons, staff, coaches, volunteers and officials for their commitment to this championship. To the competitors: thank you for showcasing your outstanding skill and sportsmanship at this championship. Please enjoy the event to the fullest – we look to this showcase of junior squash at its very best. Sincerely, Kevin D. Klipstein President & CEO EVENT SCHEDULE Trinity-PawlingBoarding and Day for Boys GradesSchool 7-12 / PG FRIDAY, DECEMBER 13 12:00-7:00pm Registration open at Harvard Murr Center 12:00-9:00pm Practice courts available at Harvard Campus PREVIEW DAY JANUARY 25, 2020 SATURDAY, DECEMBER 14 REGISTER TODAY AT 7:00am Registration opens at Harvard Murr Center www.trinitypawling.org/previewday 7:00am Lunch pickup open at Harvard for players at MIT & or call 845-855-4825 Northeastern 8:00am Matches commence at Harvard, MIT, and Northeastern 10:30am College Recruitment Info Session at the Harvard Murr Lounge (3rd floor) 11:00am Lunch opens at Harvard for participants onsite – ongoing pickup for MIT and Northeastern players 12:30pm College Recruitment Info Session at the Harvard Murr Lounge (3rd floor) 2:00pm Lunch Ends GREATNESS LIVES IN YOU. -

Afterschool Programs: Bureaucratic Barriers and Strategies for Success Effective Strategies of the Key Players

S C H O O L Strengthening the vital alliance between school board & superintendent Afterschool Programs: Bureaucratic Barriers and Strategies for Success Effective Strategies of the Key Players Why Afterschool? Where What Can You Are the Go for Barriers? Help? S traight talk By Paul D. Houston Afterschool Programs: A Historic Opportunity To Serve All Children in Yo ur District School leaders can no longer see their responsibil- consistently participate in quality afterschool ity as merely a 9 to 3 issue. What happens to children activities over a period of time have better after school has a direct impact on how they learn and grades, greater student engagement in school, grow. This issue of School Governance & Leadership increased homework completion, reduced is about afterschool programs — a powerful tool that absenteeism, less tardiness, greater parent has not been fully tapped in our efforts to guarantee involvement, lower truancy rates, increased civic children not just access to school, but success through engagement and reduced crime and violence in high achievement. This document is a companion piece the non-school hours. to the May 2005 issue of TheSchool Administrator, which focused on afterschool programs, making it AASA has been an advocate of quality afterschool clear that afterschool programs are worth the effort. programs since the early 1990s, when we collaborated As Terry Peterson, national afterschool advocate and with schools across the country to develop and sup- former counselor to Secretary of Education Richard port afterschool programs for young adolescents facing Riley, asks, in light of the hard financial times faced by multiple challenges to school and life success. -

One in Five New England Children Unsupervised After

Afterschool Advocate Page 1 of 10 Volume 7, Issue 6, July 13, 2006 ONE IN FIVE NEW ENGLAND CHILDREN UNSUPERVISED LIGHTS ON AFTERSCHOOL 2006 AFTER SCHOOL Lights on Afterschool will be Thursday, Across New England, one in five children October 12th this year! It is the only has no safe, supervised activity after the nationwide event celebrating afterschool school day ends. The lack of adult programs. Last year’s event included 7,500 supervision means these children are left to rallies. Help us grow this event and send the take care of themselves at a time of day when message that afterschool programs keep kids juvenile crime peaks, and when a range of safe, inspire them to learn, and help working inappropriate behaviors beckon, including families! Go to drugs and alcohol, gangs and teen sex. Those www.afterschoolalliance.org/lights_on/index. are among the findings of New England After cfm for tools and information, and check back 3 PM, a new report from the Afterschool often for updates. Alliance that was released in conjunction with You can also use Lights On to raise the Massachusetts Governor’s Afterschool money. Events offer sponsors valuable Summit in Boston. exposure to the media, families and While much work remains to be done customers, along with the chance to show before families’ need for afterschool they care about the community. The programs is met, New England nevertheless is Afterschool Alliance has created tools to help. showing signs of seizing national leadership Visit Funding Tools at in providing afterschool for all, the report www.afterschoolalliance.org, or says. -

Congressional Record—House H2663

May 16, 2013 CONGRESSIONAL RECORD — HOUSE H2663 has been introduced that require voters right to vote is not at the mercy of sources. He will be sorely missed and to show a photo ID. States from Vir- those acting with partisan motives. always remembered. ginia to New Mexico have considered The right to vote is not a Democratic f bills that would make voter registra- right, nor is it a Republican right. It is POVERTY IN AMERICA tion more difficult. And from Arizona an American right, and it is funda- to Tennessee, States have taken steps mental to a government for the people, The SPEAKER pro tempore. The to limit early voting. by the people. Chair recognizes the gentlewoman from Unfortunately, this plague of restric- Madam Speaker, I’m proud to sup- California (Ms. LEE) for 5 minutes. tive voting efforts has hit my State of port this bill, and I urge my colleagues Ms. LEE of California. Madam Wisconsin as well. In 2011, our legisla- to join on and protect our most funda- Speaker, as the cofounder of the Con- ture passed a law that would limit the mental right. gressional Out of Poverty Caucus and chair of the Democratic Whip Task fundamental rights Wisconsinites have f to vote. Not only would this law re- Force on Poverty and Opportunity, I quire a photo ID; it also took steps to HONORING JACOBY DICKENS rise today to continue talking about the ongoing crisis of poverty and the disenfranchise senior citizens and col- The SPEAKER pro tempore. The Chair recognizes the gentleman from impact of sequester. -

Congressional Record

E1360 CONGRESSIONAL RECORD — Extensions of Remarks June 26, 2003 CBC SPECIAL ORDER ON Along with Reverend Jackson, and many fifty-year old executive directive to end seg- AFFIRMATIVE ACTION others, I was at the Supreme Court the day regation in the military. when this case was heard. I was very proud Again, these retired military officers, like to speak to the thousands and thousands of their business counterparts, stressed that af- HON. BARBARA LEE young people led by the Michigan students firmative action is essential to the success of OF CALIFORNIA and BAM who had come to Washington from their mission. IN THE HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES all over the country to protest the effort to Diversity is a critical component of our de- eliminate affirmative action. mocracy as well. That is why I joined my Wednesday, June 25, 2003 Believe me, I see a new sense of energy and congressional colleagues, led by Michigan Ms. LEE. Mr. Speaker, I want to thank our involvement by our young people, and as Congressman John Conyers, ranking member adults we must support their organization of the Judiciary Committee and long a war- CBC Chairman, ELIJAH CUMMINGS, for holding efforts. Thank God, they are preparing them- rior in the fight for civil rights, in submit- this special order. I wish to contribute this selves to take over the world. This victory ting our own amicus brief to the Court. evening by inserting into the RECORD the fol- speaks volumes to their efforts. We asked the Court to recognize the edu- lowing speech which I delivered on Monday I was sitting in the audience when Solic- cational and political benefits of diversity; June 23, 2003 at the Rainbow Push Coalition itor General Ted Olson, the Administration’s to uphold the use of race as one factor and the Citizen Education Fund’s Women’s attorney, passionately argued against af- among others that can be considered in gov- Luncheon in Chicago. -

2015-2016 Annual Report Squashbusters’ Mission Is to Challenge and Nurture Urban Youth — As Students, Athletes

2015-2016 ANNUAL REPORT SQUASHBUSTERS’ MISSION IS TO CHALLENGE AND NURTURE URBAN YOUTH — AS STUDENTS, ATHLETES AND CITIZENS — SO THAT THEY To our SQB family, RECOGNIZE AND FULFILL THEIR For many years, squash has kept my family and me fit, taught FULLEST POTENTIAL IN LIFE. us grit and perseverance, and connected us to a network of wonderful people through practice and competitive play. I’ve always known the sport’s potential to do the same for others, SQUASHBUSTERS WAS FOUNDED and since joining the SquashBusters Board in 2008, the program’s incredible impact on its students and their families IN 1996 AS THE COUNTRY’S FIRST has been even greater than I imagined. Over the past 20 URBAN SQUASH AND EDUCATION years, SQB students have consistently graduated high school and matriculated to college at a dramatically higher rate than PROGRAM. ITS PIONEERS WERE 24 their peers, with 99% of program graduates enrolling in college and 78% graduating within six years. In 2015-2016, MIDDLE SCHOOL STUDENTS FROM we continued this success and celebrated a growing program, CAMBRIDGE AND BOSTON. new partnerships, and record-setting events. In 2015-2016, SquashBusters served more young people from Boston and Lawrence than ever before, ending the year with over 200 middle and high school students across both cities. While our tried and true program in Boston has held steady, changing the lives of students from 7th through 12th grade, John, right, with two other loyal friends of SQB: our program in Lawrence continues to grow, one grade at Thierry Lincou, center and Andy Goldfarb, left a time. -

2018 Audited Financial Statements

SQUASHBUSTERS, INC. FINANCIAL STATEMENTS YEAR ENDED JUNE 30, 2018 SQUASHBUSTERS, INC. TABLE OF CONTENTS YEAR ENDED JUNE 30, 2018 Page Independent Auditor’s Report 1 - 2 Financial Statements Statement of Financial Position 3 Statement of Activities and Changes in Net Assets 4 Statement of Functional Expenses 5 Statement of Cash Flows 6 Notes to Financial Statements 7 - 15 Supplementary Information Statements of Activities for the Years Ended June 30, 2018 and 2017 16 Board of Directors Squashbusters, Inc. 795 Columbus Avenue Roxbury Crossing, MA 02120-2108 Re: Independent Auditor’s Report Ladies and Gentlemen: We have audited the accompanying financial statements of Squashbusters, Inc. (a Massachusetts nonprofit organization), which comprise the statement of financial position as of June 30, 2018, and the related statement of activities and changes in net assets, cash flow, and functional expenses for the year then ended, and the related notes to the financial statements. Management’s Responsibility for the Financial Statements Management is responsible for the preparation and fair presentation of these financial statements in accordance with accounting principles generally accepted in the United States of America; this includes the design, implementation, and maintenance of internal control relevant to the preparation and fair presentation of financial statements that are free from material misstatement, whether due to fraud or error. Auditor’s Responsibility Our responsibility is to express an opinion on these financial statements based on our audit. We conducted our audit in accordance with auditing standards generally accepted in the United States of America. Those standards require that we plan and perform the audits to obtain reasonable assurance about whether the financial statements are free of material misstatement. -

Community Resource Manual 2017

Merrimack Valley Community Resource Manual 2017 CHILDREN’S LAW CENTER OF MASSACHUSETTS YOUTH AT RISK A Salem State University Community Program About this Manual This manual is intended to be used as a guide to the many organizations that serve low-income youth and families in the Essex County parts of Merrimack Valley, which include the towns of Amesbury, Andover, Boxford, Georgetown, Groveland, Haverhill, Ipswich, Lawrence, Merrimac, Methuen, Newbury, Newburyport, North Andover, Rowley, Salisbury, Topsfield, and West Newbury. Please note that even if an agency or program serves outside this geographic area, only these cities/towns are listed to conserve space. In the first section, providers are grouped by the type of services they offer. Because some organizations are listed more than once, all details about an organization, including all offices that serve Merrimack Valley, will appear in the first entry. Successive entries will contain only the name of the provider; relevant phone number or website, office information, and services; and the page number on which the complete details of the organization can be found. New in this Merrimack Valley edition, we have added an index. Check it out! We apologize for any omissions of, or mistakes relative to, the names of and/or information about organizations. We will endeavor to correct those omissions/mistakes in future editions. In this edition, we have included only programs and services to which a family may self-refer. We hope to expand to all programs/services in future editions. Feel free to e-mail us at [email protected] or contact us by telephone or by mail with changes, additions, or deletions. -

The National Park Service's

AS DIFFICULT AS POSSIBLE: THE NATIONAL PARK SERVICE’S IMPLEMENTATION OF THE GOVERN- MENT SHUTDOWN JOINT HEARING BEFORE THE COMMITTEE ON OVERSIGHT AND GOVERNMENT REFORM AND THE COMMITTEE ON NATURAL RESOURCES HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES ONE HUNDRED THIRTEENTH CONGRESS FIRST SESSION OCTOBER 16, 2013 Serial No. 113–116 (Committee on Oversight and Government Reform) Serial No. 113–48 (Committee on Natural Resources) ( Available via the World Wide Web: http://www.fdsys.gov http://www.house.gov/reform http://naturalresources.house.gov U.S. GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE 88–621PDF WASHINGTON : 2014 For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office Internet: bookstore.gpo.gov Phone: toll free (866) 512–1800; DC area (202) 512–1800 Fax: (202) 512–2104 Mail: Stop IDCC, Washington, DC 20402–0001 VerDate Aug 31 2005 10:23 Jul 23, 2014 Jkt 000000 PO 00000 Frm 00001 Fmt 5011 Sfmt 5011 C:\DOCS\88621.TXT APRIL COMMITTEE ON OVERSIGHT AND GOVERNMENT REFORM DARRELL E. ISSA, California, Chairman JOHN L. MICA, Florida ELIJAH E. CUMMINGS, Maryland, Ranking MICHAEL R. TURNER, Ohio Minority Member JOHN J. DUNCAN, JR., Tennessee CAROLYN B. MALONEY, New York PATRICK T. MCHENRY, North Carolina ELEANOR HOLMES NORTON, District of JIM JORDAN, Ohio Columbia JASON CHAFFETZ, Utah JOHN F. TIERNEY, Massachusetts TIM WALBERG, Michigan WM. LACY CLAY, Missouri JAMES LANKFORD, Oklahoma STEPHEN F. LYNCH, Massachusetts JUSTIN AMASH, Michigan JIM COOPER, Tennessee PAUL A. GOSAR, Arizona GERALD E. CONNOLLY, Virginia PATRICK MEEHAN, Pennsylvania JACKIE SPEIER, California SCOTT DESJARLAIS, Tennessee MATTHEW A. CARTWRIGHT, Pennsylvania TREY GOWDY, South Carolina TAMMY DUCKWORTH, Illinois BLAKE FARENTHOLD, Texas ROBIN L. -

Congressional Arts Report Card 2018 Your Guide to Voting for the Arts

CONGRESSIONAL ARTS REPORT CARD 2018 YOUR GUIDE TO VOTING FOR THE ARTS SEPTEMBER 2018 TABLE OF CONTENTS Vote smART: Will the Midterms Be a “Wave” Election? Vote smART 1 On November 6, 2018, elections will be held for all 435 seats in the U.S. House of Two-Year Timeline 2 Representatives, as well as for six non-voting delegates. A third of the Senate (35 seats) 3 A Pro-Arts Congress will also be up for election. Specically, Democrats must defend 26 of the 35 Senate seats 4 House Arts & STEAM Caucuses this year, while only nine seats will be defended by Republicans. Of note, 10 of these NEA Appropriations History 5 Democratic Senators represent states that President Trump won in 2016. While this House Grading System 6 might be indicative of a tougher re-election bid for a Democrat, this could also become an advantage in those “purple” states where the President’s popularity continues to vacillate. Pro-Arts House Leaders 7 House Arts Indicators 8 Currently, Republicans control the slimmest of margins in the Senate with 51 GOP House Report Card 9-17 members to 49 Democrats. Prospects of majority control ipping in the Senate appear to be a toss-up, since Democrats would have to win all 26 of their Senate seats as well as pick Senate Grading System 18 up two Republican-held seats. The most endangered GOP Senate seats include Senator Pro-Arts Senate Leaders 19 Dean Heller of Nevada and the two open seats currently held by retiring Senators Je Senate Arts Indicators 20 Flake of Arizona and Bob Corker of Tennessee. -

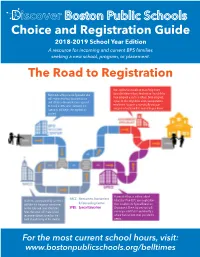

Choice and Registration Guide 2018-2019 School Year Edition a Resource for Incoming and Current BPS Families Seeking a New School, Program, Or Placement

Choice and Registration Guide 2018-2019 School Year Edition A resource for incoming and current BPS families seeking a new school, program, or placement. The Road to Registration Your application travels on to an Assignment Meet with a Registration Specialist who Specialist where it has a final review. Your child is will review residency documentation then assigned a seat in a school. Once assigned, and all other documentation required if your child is eligible for a bus, transportation to enroll in BPS; once reviewed, the enrollment happens automatically and your Specialist will begin the registration assignment notice will be mailed to your home. process. If your child has an Individualized NACC: Newcomers Assessment Students, accompanied by parent(s), Education Plan (IEP), your application will take the language assessment & Counseling Center then travels to the Special Education on the date and time scheduled. SPED: Special Education Department. There, trained staff will After, the tester will make school review your child’s IEP and identify a recommendations based on the school that can best serve your child’s level of proficiency of the student. needs. For the most current school hours, visit: www.bostonpublicschools.org/belltimes IntroductionTitle IMPORTANT DATES Start of End of Priority Priority Assignment Registration Registration Notifications Students January February March entering grades K0, K1, 6, 7, or 9. 3 9 30 February March May Students in all OTHER grades. 12 23 31 oston Public Schools offer academic, social-emotional, cultural, and extracurricular programs that meet the diverse needs of all families across the city. From pre-kindergarten through Bmiddle school and continuing through high school, our schools strive to develop in every learner the knowledge, skills, and character to excel in college, career, and life.