ED316172.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Princeton Alumni Weekly

00paw0206_cover3NOBOX_00paw0707_Cov74 1/22/13 12:26 PM Page 1 Arts district approved Princeton Blairstown soon to be on its own Alumni College access for Weekly low-income students LIVES LIVED AND LOST: An appreciation ! Nicholas deB. Katzenbach ’43 February 6, 2013 • paw.princeton.edu During the month of February all members save big time on everyone’s favorite: t-shirts! Champion and College Kids brand crewneck tees are marked to $11.99! All League brand tees and Champion brand v-neck tees are reduced to $17.99! Stock up for the spring time, deals like this won’t last! SELECT T-SHIRTS FOR MEMBERS ONLY $11.99 - $17.99 3KRWR3ULQFHWRQ8QLYHUVLW\2I¿FHRI&RPPXQLFDWLRQV 36 UNIVERSITY PLACE CHECK US 116 NASSAU STREET OUT ON 800.624.4236 FACEBOOK! WWW.PUSTORE.COM February 2013 PAW Ad.indd 3 1/7/2013 4:16:20 PM 01paw0206_TOCrev1_01paw0512_TOC 1/22/13 11:36 AM Page 1 Franklin A. Dorman ’48, page 24 Princeton Alumni Weekly An editorially independent magazine by alumni for alumni since 1900 FEBRUARY 6, 2013 VOLUME 113 NUMBER 7 President’s Page 2 Inbox 5 From the Editor 6 Perspective 11 Unwelcome advances: A woman’s COURTESY life in the city JENNIFER By Chloe S. Angyal ’09 JONES Campus Notebook 12 Arts district wins approval • Committee to study college access for low-income Lives lived and lost: An appreciation 24 students • Faculty divestment petition PAW remembers alumni whose lives ended in 2012, including: • Cost of journals soars • For Mid east, a “2.5-state solution” • Blairs town, Charles Rosen ’48 *51 • Klaus Goldschlag *49 • University to cut ties • IDEAS: Rise of the troubled euro • Platinum out, iron Nicholas deB. -

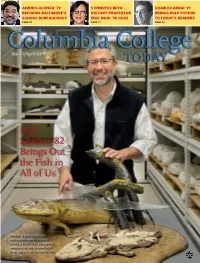

Neil Shubin '82 Brings out the Fish in All of Us

ANDRES ALONSO ’79 5 MINUTES WITH … CHARLES ARDAI ’91 REFORMS BALTIMORE’S HISTORY PROFESSOR BRINGS PULP FICTION SCHOOL BUREAUCRACY MAE NGAI ’98 GSAS TO TODAY’S READERS PAGE 22 PAGE 11 PAGE 24 Columbia College March/April 2011 TODAY Neil Shubin ’82 Brings Out the Fish in All of Us Shubin, a paleontologist and evolutionary biologist, co-led a team that discovered evidence of the pivotal shift from aquatic to terrestrial life. ust another J membership perk. Meet. Dine. Entertain. Join the Columbia Club and access state-of-the-art meeting rooms for your conferences and events. For more information or to apply, visit www.columbiaclub.org or call (212) 719-0380. The Columbia University Club of New York in residence at 15 West 43 St. New York, N Y 10036 Columbia’s SocialIntellectualCulturalRecreationalProfessional Resource in Midtown. Columbia College Today Contents 22 12 24 7 56 18 COVER STORY ALUMNI NEWS DEPARTMENTS G O FISH 27 O BITUARIES 2 LETTERS TO THE 12 Paleontologist and evolutionary biologist Neil Shubin 27 Joseph D. Coffee Jr. ’41 EDITOR ’82 brings out the fish in all of us. 28 Garland E. Wood ’65 3 ITHIN THE AMILY By Nathalie Alonso ’08 W F 30 B OOKSHEL F 4 AROUND THE QUADS FEATURES Featured: Adam Gidwitz ’04 4 turns classic folklore on its Northwest Corner Building Opens COLUMBIA FORUM ear with his new children’s 18 book, A Tale Dark & Grimm. 5 Rose, Jones Join In an excerpt from his book How Soccer Explains the College Senior Staff World: An Unlikely Theory of Globalization, Franklin 32 LASS OTES 6 Creed To Deliver Foer ’96 explains how one soccer club’s destiny was C N A LUMNI PRO F ILES Class Day Address shaped by European anti-Semitism. -

The Science of Stories

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by ResearchArchive at Victoria University of Wellington The Science of Stories Human History and the Narrative Philosophy of Science by Robert Alexander Hurley A thesis presented to the Victoria University of Wellington in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Victoria University of Wellington 2012 Abstract There is a pronounced tendency within contemporary philosophy of history to think of historical knowledge as something apart from the kind of knowledge generated in the sciences. This has given rise to a myriad of epistemological issues. For if historical knowledge is not related to the scientific, then what is it? By what logic does it proceed? How are historical conclusions justified? Although almost the entirety of contemporary philosophy of history has been dedicated to such questions, there has been little real and agreed upon progress. Rather than fire yet another salvo in this rhetorical war, however, this thesis wishes instead to examine what lies beneath the basic presumption of separatism which animates it. Part One examines several paradigmatic examples of twentieth century philosophy of history in order to identify the grounds by which their authors considered history fundamentally different in kind from the sciences. It is concluded that, in each case, the case for separatism fows from the pervasive assumption that any body of knowledge which might rightly be called a science can be recognised by its search for general laws of nature. As history does not seem to share this aim, it is therefore considered to be knowledge of a fundamentally different kind. -

The Science of Stories

The Science of Stories Human History and the Narrative Philosophy of Science by Robert Alexander Hurley A thesis presented to the Victoria University of Wellington in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Victoria University of Wellington 2012 Abstract There is a pronounced tendency within contemporary philosophy of history to think of historical knowledge as something apart from the kind of knowledge generated in the sciences. This has given rise to a myriad of epistemological issues. For if historical knowledge is not related to the scientific, then what is it? By what logic does it proceed? How are historical conclusions justified? Although almost the entirety of contemporary philosophy of history has been dedicated to such questions, there has been little real and agreed upon progress. Rather than fire yet another salvo in this rhetorical war, however, this thesis wishes instead to examine what lies beneath the basic presumption of separatism which animates it. Part One examines several paradigmatic examples of twentieth century philosophy of history in order to identify the grounds by which their authors considered history fundamentally different in kind from the sciences. It is concluded that, in each case, the case for separatism fows from the pervasive assumption that any body of knowledge which might rightly be called a science can be recognised by its search for general laws of nature. As history does not seem to share this aim, it is therefore considered to be knowledge of a fundamentally different kind. This thesis terms this the "nomothetic assumption.” Part Two argues that such nomothetic assumptions are not an accurate representation of either scientific theory or practice and therefore that any assumption of separatism based upon them is unsound. -

The Story of Sue the T-Rex and Controversy Over Access to Fossils

HPLS (2020) 42:2 https://doi.org/10.1007/s40656-019-0288-4 ORIGINAL PAPER Assumptions of authority: the story of Sue the T‑rex and controversy over access to fossils Elizabeth D. Jones1,2 Received: 26 October 2018 / Accepted: 11 October 2019 © The Author(s) 2019 Abstract Although the buying, selling, and trading of fossils has been a princi- ple part of paleontological practice over the centuries, the commercial collection of fossils today has re-emerged into a pervasive and lucrative industry. In the United States, the number of commercial companies driving the legal, and sometimes ille- gal, selling of fossils is estimated to have doubled since the 1980s, and worries from academic paleontologists over this issue has increased accordingly. Indeed, some view the commercialization of fossils as one of the greatest threats to paleontology today. In this article, I address the story of “Sue”—the largest, most complete, and most expensive Tyrannosaurus rex ever excavated—whose discovery incited a series of high-profle legal battles throughout the 1990s over the question of “Who owns Sue?” Over the course of a decade, various stakeholders from academic paleontolo- gists and fossil dealers to Native Americans, private citizens, and government of- cials all laid claim to Sue. In exploring this case, I argue that assumptions of author- ity are responsible for initiating and sustaining debates over fossil access. Here, assumptions of authority are understood as assumptions of ownership, or expertise, or in some cases both. Viewing the story from this perspective illuminates the sig- nifcance of fossils as boundary objects. It also highlights the process of boundary- work by which individuals and groups constructed or deconstructed borders around Sue (specifcally) and fossil access (more generally) to establish their own authority. -

The Palaeontology Newsletter

The Palaeontology Newsletter Contents 89 Editorial 2 Association Business 3 Association Meetings 28 Palaeontology at EGU 33 News 34 From our correspondents Legends of Rock: Murchison 43 Behind the scenes at the Museum 46 Buffon’s Gang 51 R: Regression 58 PalAss press releases 68 Blaschka glass models 69 Sourcing the Ring Master 73 Underwhelming fossil of the month 75 Future meetings of other bodies 80 Meeting Reports 87 Obituaries Percy Milton Butler 100 Lennart Jeppsson 103 Grant and Bursary reports 106 Book Reviews 116 Careering off course! 121 Palaeontology vol 58 parts 3 & 4 123–124 Papers in Palaeontology, vol 1, part 1 125 Reminder: The deadline for copy for Issue no 90 is 12th October 2015. On the Web: <http://www.palass.org/> ISSN: 0954-9900 Newsletter 89 2 Editorial Here in London summer is under way, although it is difficult to tell just by looking out of the window; once you step outside, however, the high pollen counts are the main giveaway. It is largely the sort of ‘summer’ weather that confuses foreign tourists, makes a mud bath out of music festivals and stops play at Wimbledon. The perfect sort of weather to leave Britain behind and jet off to sunnier climes for a nice long field campaign: as I wistfully gaze at the grey skies I wish I were packing my notebook and field gear ready for departure. Those of you who are setting out for fieldwork during this Northern Hemisphere summer will probably be aware that it is not a walk in the park, as my initial rose-tinted memories lead me to believe. -

Top of Page Interview Information--Different Title

i Oral History Center University of California The Bancroft Library Berkeley, California Caution and Care: The Evolution of Paleontology at the University of California Museum of Paleontology: Volume II Interviews with David Archibald Mike Novacek Annalisa Berta Lowell Dingus Marisol Montellano Zhe-Xi Luo Charles Marshall Nancy Simmons Don Lofgren David Polly Jessica Theodor Greg Wilson Mark Goodwin Interviews conducted by Paul Burnett in 2015 and 2016 Copyright © 2017 by The Regents of the University of California ii Table of Contents Interview History by Paul Burnett iii Introduction by Jason A. Lillegraven v David Archibald 1 Mike Novacek 23 Annalisa Berta 43 Lowell Dingus 69 Marisol Montellano 89 Zhe-Xi Luo 113 Charles Marshall 135 Nancy Simmons 163 Don Lofgren 189 David Polly 215 Jessica Theodor 241 Greg Wilson 265 Mark Goodwin 289 iii Interview History The Bill Clemens/UCMP oral history project has been several years in the making. Historian Sam Redman first proposed to do a history of members of the University of California Museum of Paleontology in 2011, specifically to interview Dr. William Clemens and a number of his graduate students. The concept behind the project was novel and important: to document with long-form oral history of successive cohorts of students who were advised by a single scholar, while at the same time interviewing the scholar in depth about the evolution of his field, as well as the key transformations in the institutions in which he played significant roles. UCMP Associate Director Mark Goodwin was the fulcrum in organizing the project, from fundraising to arranging for interviews with Bill’s students from all over the world. -

ANNUAL REPORT Harvard University

MUSEUM OF COMPARATIVE ZOOLOGY ANNUAL REPORT HARVARD UNIVERSITY 2010–2011 ANNUAL REPORT 2010–2011 1 DIRECTOR’S MESSAGE Professor Ernst Mayr, arguably the most famous evolutionary biologist of the 20th century, served as MCZ’s director from 1961 to 1970. For him, the MCZ “is not merely a repository of collections but a biological research institute.” According to Mayr, the MCZ has two explicit This past year saw significant improvements tasks: “to study the diversity of living nature to our physical plant. A new cryogenic lab and its evolution—the mere accumulation was installed, which will house a state-of-the- of specimens and the mere description of art, liquid-nitrogen-based collection that will new species is not our primary task”—and come online in November 2011. Build-out of to instruct undergraduate and graduate the MCZ’s new 50,000-square-foot collections students. This past year’s activities and events facility in the Northwest Science Building show that we are doing our best to promote began in spring 2011. Migration of specimens and realize Mayr’s lofty vision and maintain from their current, overcrowded space in the MCZ’s standing as the finest university-based old MCZ will begin in early 2012. natural history museum in the world. With the acquisition of several grants, MCZ Perhaps the most important ongoing activity is able to participate in both national and of any university-based museum is the global efforts to digitize collection records, hiring and retention of outstanding faculty- some of which extend back hundreds curators. Hence, I’m happy to announce of years. -

Fishing for Answers

the bones of a strange flat-headed, fish- ALUMNI cum-crocodile-like creature-with-a-neck that he and colleagues had found the year before while scraping away at ancient rocks in the Canadian Arctic. Fishing for Answers Roughly 375 million years old, from the Late Devonian period, the fossilized crea- ture was a genus of the extinct sarcop- A paleontologist looks at the origins of the human body. terygian (lobe-finned) fish that shares sev- eral key features with tetrapods (early n 2005, parents and school o∞cials parents’ favor, deciding that the require- four-legged animals). In addition to the in Dover, Pennsylvania, were locked ment was unconstitutional. Throughout neck and non-conical head, Tiktaalik roseae, in a courtroom debate over a school- the trial, paleontologist Neil Shubin, as it was named, boasted expanded ribs board mandate that intelligent de- Ph.D. ’87, Bensley professor in the depart- and parts of a shoulder, along with Isign be presented as an alternative to evo- ment of organismal biology and anatomy webbed fins—inside which were also lution in ninth-grade science classes. The at the University of Chicago, struggled to primitive bones corresponding to an upper judge in the case ultimately ruled in the remain quiet in his o∞ce: on his desk lay arm, forearm, and pieces of a wrist. All are explicitly non-fish features. Shubin and Neil Shubin other scientists say Tiktaalik helps bridge the gap in our understanding of what changes occurred as sea animals crept ashore, and plays a critical role in under- standing—and proving—human origins. -

Gayat Princeton

00paw0403_coverNOBOX_00paw0707_Cov74 3/19/13 4:17 PM Page 1 Coping with Princeton climate change Boom times for Alumni computer science Weekly Texting’s downside GAY AT PRINCETON ALUMNI SPEAK OUT ABOUT A TIME WHEN THEY WERE SILENT April 3, 2013 • paw.princeton.edu Also during Reunions Weekend: Remembering Butler: A Video Storytelling Project Demolition Date: Summer/Fall 2014 Services University Yoon, Michael by Photo Did you live here? If so, we want to hear your story. Come to Reunions and participate in the “Remembering Butler” project created to record your stories about life at Butler. Sign up for interview times on the APGA’s Reunions website: APGA Reunions 2013: May 30-June 2 http://alumni.princeton.edu/apga/reunions/ The Association of Princeton Graduate Alumni invites graduate alumni and guests back to campus to celebrate with old and th new friends as we honor the 100 anniversary of the Graduate The Fight of the Century: The Thrill-A on the Hill-A College and our lives as graduate students with our theme, GCentennial: Living it Up! Whether you lived in the GC, Butler, Hibben-Magie, Lawrence, Stanworth, or anywhere else, let’s celebrate the good memories and make some new ones at this year’s Reunions. Event Highlights: Friday, 5/31 t Alumni Faculty Forums featuring several graduate alumni panelists t Welcome Reception kicking o" Reunions weekend at the APGA Tent t Late Night Party at the APGA Tent featuring live music from Brian Kirk & the Jirks – open to all Reunions attendees! ’73 Mills Saturday, 6/1 t Cleveland Tower Climb -

Annual Report Harvard University

MUSEUM OF COMPARATIVE ZOOLOGY ANNUAL REPORT HARVARD UNIVERSITY 2012–2013 ANNUAL REPORT 2012–2013 4 DIRECTOR’S MESSAGE Determination, persistence, stamina, confidence, inquisitiveness and patience are among the cornerstones of a successful career in science. Humor, wit, stubbornness and charm don’t center for research and education in hurt either. These characteristics and more comparative biology are highlighted in made Farish A. Jenkins Jr. an esteemed this report. By participating in national mentor, teacher, colleague and friend to initiatives such as Advancing Integration many—in fact, to just about everyone. On of Museums into Undergraduate Programs, November 11, 2012, we said goodbye to this Network Integrated Biocollections Alliance beloved member of the MCZ. Farish touched and Advancing Digitization of Biological us deeply, and he is remembered fondly by all Collections, we are developing and who knew him. He really was one of a kind. implementing new tools that foster access to and utilization of museum In anticipation of Farish’s retirement, which collections. And the Encyclopedia of had been scheduled for this past summer, Life Learning + Education Group, based last year we launched a formal search here, continues to develop innovative to hire his successor as MCZ’s Curator ways to promote bioliteracy worldwide. of Vertebrate Paleontology and faculty member in Organismic and Evolutionary Beginning two years ago, the Faculty of Biology. This search concluded successfully, Arts and Sciences initiated a major effort Catherine Weisel and I am extremely pleased to introduce to strengthen, support and highlight the Dr. Stephanie Pierce, BSc, MSc, PhD, and public activities of its six research and welcome her to the MCZ. -

SVP News Bulletin, February 1995, Number

Number 166, February 1996 © 1996, The Society of Vertebrate Paleontology SVP News Bulletin Number 166, February 1996 1 -- TABLE OF CONTENTS -- Official Business 2 Committee Reports 15 Committee Listings 36 New Members 51 Address Changes 56 News From Members 73 Bulletin Board 114 Calendar of Events 115 Publications 117 Positions Available 117 Obituaries 119 Statement of Ethics 128 OFFICIAL BUSINESS -- Minutes of the 55th Annual Business Meeting, November 3, 1995, Pittsburgh, Penna. David Krause, President, called the meeting to order at 3:17 PM and welcomed the group to the 55th annual meeting. He then recognized the SVP staff, Pamela D'Argo and Kathleen Lundgren for their hard work in assisting with the meeting. John Flynn, Secretary, gave his report which included the following motion: to accept the minutes as presented from the 54th annual meeting. The motion was seconded and carried. Flynn reviewed the officer election results as follows: John Bolt, Treasurer; J. Flynn, Secretary; and Elizabeth Nicholls, Member-at-Large. Flynn then noted the current membership total of 1,500. Flynn also summarized the outcome of the June 1995 Executive Committee meeting. Lastly, Flynn noted that he would be working with the Executive Committee to make major revisions to the constitution and bylaws, as they are currently out of date. Annalisa Berta, Information Management Committee Chair, gave the Information Management report. Berta reviewed the following committee accomplishments: listserve participants = 470; developing a home page on the World Wide Web for debut next year; electronic BFV data (equaling 21,000 references) from volumes 1981-1990 with 1,300 queries being placed thus far.