Top of Page Interview Information--Different Title

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Newsletter 22/06 DIGITAL EDITION Nr

ISSN 1610-2606 ISSN 1610-2606 newsletter 22/06 DIGITAL EDITION Nr. 193 - Oktober 2006 Michael J. Fox Christopher Lloyd LASER HOTLINE - Inh. Dipl.-Ing. (FH) Wolfram Hannemann, MBKS - Talstr. 3 - 70825 K o r n t a l Fon: 0711-832188 - Fax: 0711-8380518 - E-Mail: [email protected] - Web: www.laserhotline.de Newsletter 22/06 (Nr. 193) Oktober 2006 editorial Hallo Laserdisc- und DVD-Fans, diesem Sinne sind wir guten Mutes, unse- liebe Filmfreunde! ren Festivalbericht in einem der kommen- Kennen Sie das auch? Da macht man be- den Newsletter nachzureichen. reits während der Fertigstellung des einen Newsletters große Pläne für den darauf Aber jetzt zu einem viel wichtigeren The- folgenden nächsten Newsletter und prompt ma. Denn wer von uns in den vergangenen wird einem ein Strich durch die Rechnung Wochen bereits die limitierte Steelbook- gemacht. So in unserem Fall. Der für die Edition der SCANNERS-Trilogie erwor- jetzt vorliegende Ausgabe 193 vorgesehene ben hat, der darf seinen ursprünglichen Bericht über das Karlsruher Todd-AO- Ärger über Teil 2 der Trilogie rasch ver- Festival musste kurzerhand wieder auf Eis gessen. Hersteller Black Hill ließ Folgen- gelegt werden. Und dafür gibt es viele gute des verlautbaren: Gründe. Da ist zunächst das Platzproblem. Im wahrsten Sinne des Wortes ”platzt” der ”Käufer der Verleih-Fassung der Scanners neue Newsletter wieder aus allen Nähten. Box haben sicherlich bemerkt, dass der Wenn Sie also bislang zu jenen Unglückli- 59 prall gefüllte Seiten - und das nur mit zweite Teil um circa 100 Sekunden gekürzt chen gehören, die SCANNERS 2 nur in anstehenden amerikanischen Releases! Des ist. -

Princeton Alumni Weekly

00paw0206_cover3NOBOX_00paw0707_Cov74 1/22/13 12:26 PM Page 1 Arts district approved Princeton Blairstown soon to be on its own Alumni College access for Weekly low-income students LIVES LIVED AND LOST: An appreciation ! Nicholas deB. Katzenbach ’43 February 6, 2013 • paw.princeton.edu During the month of February all members save big time on everyone’s favorite: t-shirts! Champion and College Kids brand crewneck tees are marked to $11.99! All League brand tees and Champion brand v-neck tees are reduced to $17.99! Stock up for the spring time, deals like this won’t last! SELECT T-SHIRTS FOR MEMBERS ONLY $11.99 - $17.99 3KRWR3ULQFHWRQ8QLYHUVLW\2I¿FHRI&RPPXQLFDWLRQV 36 UNIVERSITY PLACE CHECK US 116 NASSAU STREET OUT ON 800.624.4236 FACEBOOK! WWW.PUSTORE.COM February 2013 PAW Ad.indd 3 1/7/2013 4:16:20 PM 01paw0206_TOCrev1_01paw0512_TOC 1/22/13 11:36 AM Page 1 Franklin A. Dorman ’48, page 24 Princeton Alumni Weekly An editorially independent magazine by alumni for alumni since 1900 FEBRUARY 6, 2013 VOLUME 113 NUMBER 7 President’s Page 2 Inbox 5 From the Editor 6 Perspective 11 Unwelcome advances: A woman’s COURTESY life in the city JENNIFER By Chloe S. Angyal ’09 JONES Campus Notebook 12 Arts district wins approval • Committee to study college access for low-income Lives lived and lost: An appreciation 24 students • Faculty divestment petition PAW remembers alumni whose lives ended in 2012, including: • Cost of journals soars • For Mid east, a “2.5-state solution” • Blairs town, Charles Rosen ’48 *51 • Klaus Goldschlag *49 • University to cut ties • IDEAS: Rise of the troubled euro • Platinum out, iron Nicholas deB. -

TOKYO GAME SHOW 2011 Visitors Survey Report November 2011

TOKYO GAME SHOW 2011 Visitors Survey Report November 2011 Computer Entertainment Supplier's Association ■ Contents ■ Outline of Survey 3 Ⅰ.Visitors' Characteristics 4 1.Gender -------------------------------------------------------------------------- 4 2.Age ---------------------------------------------------------------------------- 4 3.Residential area --------------------------------------------------------------- 5 4.Occupation --------------------------------------------------------------------- 5 5.Hobbies and interests --------------------------------------------------------------- 6 Ⅱ.Household Videogames 9 1.Hardware ownership・Hardware most frequently used -------------------------------------- 9 2.Hardware the respondents wish to purchase --------------------------------------------- 12 3.Favorite game genres ---------------------------------------------------------------- 15 4.Frequency of game playing ----------------------------------------------------------- 19 5.Duration of game playing ------------------------------------------------------------- 21 6.Tendency of software purchases ------------------------------------------------------ 24 7.Tendency of software purchases by downloading ----------------------------------------- 27 Ⅲ.Social Games 28 1.Familiarity with SNS and social games -------------------------------------------------- 28 2.Hardware used for SNS 【All SNS users】 ------------------------------------------------ 31 3.Frequency of game playing 【All social game players】 ------------------------------------- -

Sailor Mars Meet Maroku

sailor mars meet maroku By GIRNESS Submitted: August 11, 2005 Updated: August 11, 2005 sailor mars and maroku meet during a battle then fall in love they start to go futher and futher into their relationship boy will sango be mad when she comes back =:) hope you like it Provided by Fanart Central. http://www.fanart-central.net/stories/user/GIRNESS/18890/sailor-mars-meet-maroku Chapter 1 - sango leaves 2 Chapter 2 - sango leaves 15 1 - sango leaves Fanart Central A.whitelink { COLOR: #0000ff}A.whitelink:hover { BACKGROUND-COLOR: transparent}A.whitelink:visited { COLOR: #0000ff}A.BoxTitleLink { COLOR: #000; TEXT-DECORATION: underline}A.BoxTitleLink:hover { COLOR: #465584; TEXT-DECORATION: underline}A.BoxTitleLink:visited { COLOR: #000; TEXT-DECORATION: underline}A.normal { COLOR: blue}A.normal:hover { BACKGROUND-COLOR: transparent}A.normal:visited { COLOR: #000020}A { COLOR: #0000dd}A:hover { COLOR: #cc0000}A:visited { COLOR: #000020}A.onlineMemberLinkHelper { COLOR: #ff0000}A.onlineMemberLinkHelper:hover { COLOR: #ffaaaa}A.onlineMemberLinkHelper:visited { COLOR: #cc0000}.BoxTitleColor { COLOR: #000000} picture name Description Keywords All Anime/Manga (0)Books (258)Cartoons (428)Comics (555)Fantasy (474)Furries (0)Games (64)Misc (176)Movies (435)Original (0)Paintings (197)Real People (752)Tutorials (0)TV (169) Add Story Title: Description: Keywords: Category: Anime/Manga +.hack // Legend of Twilight's Bracelet +Aura +Balmung +Crossovers +Hotaru +Komiyan III +Mireille +Original .hack Characters +Reina +Reki +Shugo +.hack // Sign +Mimiru -

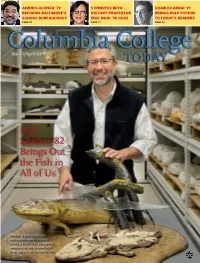

Neil Shubin '82 Brings out the Fish in All of Us

ANDRES ALONSO ’79 5 MINUTES WITH … CHARLES ARDAI ’91 REFORMS BALTIMORE’S HISTORY PROFESSOR BRINGS PULP FICTION SCHOOL BUREAUCRACY MAE NGAI ’98 GSAS TO TODAY’S READERS PAGE 22 PAGE 11 PAGE 24 Columbia College March/April 2011 TODAY Neil Shubin ’82 Brings Out the Fish in All of Us Shubin, a paleontologist and evolutionary biologist, co-led a team that discovered evidence of the pivotal shift from aquatic to terrestrial life. ust another J membership perk. Meet. Dine. Entertain. Join the Columbia Club and access state-of-the-art meeting rooms for your conferences and events. For more information or to apply, visit www.columbiaclub.org or call (212) 719-0380. The Columbia University Club of New York in residence at 15 West 43 St. New York, N Y 10036 Columbia’s SocialIntellectualCulturalRecreationalProfessional Resource in Midtown. Columbia College Today Contents 22 12 24 7 56 18 COVER STORY ALUMNI NEWS DEPARTMENTS G O FISH 27 O BITUARIES 2 LETTERS TO THE 12 Paleontologist and evolutionary biologist Neil Shubin 27 Joseph D. Coffee Jr. ’41 EDITOR ’82 brings out the fish in all of us. 28 Garland E. Wood ’65 3 ITHIN THE AMILY By Nathalie Alonso ’08 W F 30 B OOKSHEL F 4 AROUND THE QUADS FEATURES Featured: Adam Gidwitz ’04 4 turns classic folklore on its Northwest Corner Building Opens COLUMBIA FORUM ear with his new children’s 18 book, A Tale Dark & Grimm. 5 Rose, Jones Join In an excerpt from his book How Soccer Explains the College Senior Staff World: An Unlikely Theory of Globalization, Franklin 32 LASS OTES 6 Creed To Deliver Foer ’96 explains how one soccer club’s destiny was C N A LUMNI PRO F ILES Class Day Address shaped by European anti-Semitism. -

Copy of Anime Licensing Information

Title Owner Rating Length ANN .hack//G.U. Trilogy Bandai 13UP Movie 7.58655 .hack//Legend of the Twilight Bandai 13UP 12 ep. 6.43177 .hack//ROOTS Bandai 13UP 26 ep. 6.60439 .hack//SIGN Bandai 13UP 26 ep. 6.9994 0091 Funimation TVMA 10 Tokyo Warriors MediaBlasters 13UP 6 ep. 5.03647 2009 Lost Memories ADV R 2009 Lost Memories/Yesterday ADV R 3 x 3 Eyes Geneon 16UP 801 TTS Airbats ADV 15UP A Tree of Palme ADV TV14 Movie 6.72217 Abarashi Family ADV MA AD Police (TV) ADV 15UP AD Police Files Animeigo 17UP Adventures of the MiniGoddess Geneon 13UP 48 ep/7min each 6.48196 Afro Samurai Funimation TVMA Afro Samurai: Resurrection Funimation TVMA Agent Aika Central Park Media 16UP Ah! My Buddha MediaBlasters 13UP 13 ep. 6.28279 Ah! My Goddess Geneon 13UP 5 ep. 7.52072 Ah! My Goddess MediaBlasters 13UP 26 ep. 7.58773 Ah! My Goddess 2: Flights of Fancy Funimation TVPG 24 ep. 7.76708 Ai Yori Aoshi Geneon 13UP 24 ep. 7.25091 Ai Yori Aoshi ~Enishi~ Geneon 13UP 13 ep. 7.14424 Aika R16 Virgin Mission Bandai 16UP Air Funimation 14UP Movie 7.4069 Air Funimation TV14 13 ep. 7.99849 Air Gear Funimation TVMA Akira Geneon R Alien Nine Central Park Media 13UP 4 ep. 6.85277 All Purpose Cultural Cat Girl Nuku Nuku Dash! ADV 15UP All Purpose Cultural Cat Girl Nuku Nuku TV ADV 12UP 14 ep. 6.23837 Amon Saga Manga Video NA Angel Links Bandai 13UP 13 ep. 5.91024 Angel Sanctuary Central Park Media 16UP Angel Tales Bandai 13UP 14 ep. -

MAD SCIENCE! Ab Science Inc

MAD SCIENCE! aB Science Inc. PROGRAM GUIDEBOOK “Leaders in Industry” WARNING! MAY CONTAIN: Vv Highly Evil Violations of Volatile Sentient :D Space-Time Materials Robots Laws FOOT table of contents 3 Letters from the Co-Chairs 4 Guests of Honor 10 Events 15 Video Programming 18 Panels & Workshops 28 Artists’ Alley 32 Dealers Room 34 Room Directory 35 Maps 41 Where to Eat 48 Tipping Guide 49 Getting Around 50 Rules 55 Volunteering 58 Staff 61 Sponsors 62 Fun & Games 64 Autographs APRIL 2-4, 2O1O 1 IN MEMORY OF TODD MACDONALD “We will miss and love you always, Todd. Thank you so much for being a friend, a staffer, and for the support you’ve always offered, selflessly and without hesitation.” —Andrea Finnin LETTERS FROM THE CO-CHAIRS Anime Boston has given me unique growth Hello everyone, welcome to Anime Boston! opportunities, and I have become closer to people I already knew outside of the convention. I hope you all had a good year, though I know most of us had a pretty bad year, what with the economy, increasing healthcare This strengthening of bonds brought me back each year, but 2010 costs and natural disasters (donate to Haiti!). At Anime Boston, is different. In the summer of 2009, Anime Boston lost a dear I hope we can provide you with at least a little enjoyment. friend and veteran staffer when Todd MacDonald passed away. We’ve been working long and hard to get composer Nobuo When Todd joined staff in 2002, it was only because I begged. Uematsu, most famous for scoring most of the music for the Few on staff imagined that our three-day convention was going Final Fantasy games as well as other Square Enix games such to be such an amazing success. -

Stephen Jay Gould Papers M1437

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/kt229036tr No online items Guide to the Stephen Jay Gould Papers M1437 Jenny Johnson Department of Special Collections and University Archives August 2011 ; revised 2019 Green Library 557 Escondido Mall Stanford 94305-6064 [email protected] URL: http://library.stanford.edu/spc Guide to the Stephen Jay Gould M1437 1 Papers M1437 Language of Material: English Contributing Institution: Department of Special Collections and University Archives Title: Stephen Jay Gould papers creator: Gould, Stephen Jay source: Shearer, Rhonda Roland Identifier/Call Number: M1437 Physical Description: 575 Linear Feet(958 boxes) Physical Description: 1180 computer file(s)(52 megabytes) Date (inclusive): 1868-2004 Date (bulk): bulk Abstract: This collection documents the life of noted American paleontologist, evolutionary biologist, and historian of science, Stephen Jay Gould. The papers include correspondence, juvenilia, manuscripts, subject files, teaching files, photographs, audiovisual materials, and personal and biographical materials created and compiled by Gould. Both textual and born-digital materials are represented in the collection. Preferred Citation [identification of item], Stephen Jay Gould Papers, M1437. Dept. of Special Collections, Stanford University Libraries, Stanford, Calif. Publication Rights While Special Collections is the owner of the physical and digital items, permission to examine collection materials is not an authorization to publish. These materials are made available for use -

Newsletter 14/09 DIGITAL EDITION Nr

ISSN 1610-2606 ISSN 1610-2606 newsletter 14/09 DIGITAL EDITION Nr. 256 - August 2009 Michael J. Fox Christopher Lloyd LASER HOTLINE - Inh. Dipl.-Ing. (FH) Wolfram Hannemann, MBKS - Talstr. 3 - 70825 K o r n t a l Fon: 0711-832188 - Fax: 0711-8380518 - E-Mail: [email protected] - Web: www.laserhotline.de Newsletter 14/09 (Nr. 256) August 2009 editorial Hallo Laserdisc- und DVD-Fans, liebe Filmfreunde! Wenn Sie sich beim Betrachten un- seres Titelbildes fragen, was Willem Dafoe hier genau mit Char- lotte Gainsbourg anstellt, dann hilft Ihnen vorerst nur der Gang ins Kino. Denn Lars von Triers neue- ster Streifen ANTICHRIST, der vor einigen Wochen in Cannes für einen handfesten Skandal sorgte, wird frühestens im kommenden Jahr auf DVD erscheinen. Warum also schmücken wir die neueste Ausgabe unseres Newsletters mit einem Motiv aus einem Film, den es vorerst noch gar nicht für die Sammlung zu erwerben gibt? Nun, wir halten es hier genauso wie der Meister selbst und geben uns ganz der Provokation hin. Sie dürfen es gerne zugeben: das Titelbild hat Sie zum Weiterlesen verführt. Außer- dem ist es doch ein ganz exquisites Stück Schwarz-Weiß-Fotografie. Oder etwa nicht? Wenn wir Sie jetzt neugierig auf ANTICHRIST gemacht haben, dann empfehlen wir Seite 7 dieses Newsletters. Denn dort erzählt Ihnen Wolfram Hannemann in seinem Filmblog, ob ANTICHRIST das hält was Herr von Trier verspricht, nämlich ein Horrorfilm zu sein. Ob Sie es nun glauben oder nicht: unser Titelbild ist nicht die einzige Provokation im neuen Newsletter. und gar nicht. Im September ga- beginnt nach 96 Stunden intensivem Denn auch unsere Kolumnistin stiert wieder einmal das Fantasy Filmkonsum J ) auf ein natürliches Anna übt sich in ihrer neuesten Ko- Filmfest in Stuttgart. -

The Science of Stories

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by ResearchArchive at Victoria University of Wellington The Science of Stories Human History and the Narrative Philosophy of Science by Robert Alexander Hurley A thesis presented to the Victoria University of Wellington in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Victoria University of Wellington 2012 Abstract There is a pronounced tendency within contemporary philosophy of history to think of historical knowledge as something apart from the kind of knowledge generated in the sciences. This has given rise to a myriad of epistemological issues. For if historical knowledge is not related to the scientific, then what is it? By what logic does it proceed? How are historical conclusions justified? Although almost the entirety of contemporary philosophy of history has been dedicated to such questions, there has been little real and agreed upon progress. Rather than fire yet another salvo in this rhetorical war, however, this thesis wishes instead to examine what lies beneath the basic presumption of separatism which animates it. Part One examines several paradigmatic examples of twentieth century philosophy of history in order to identify the grounds by which their authors considered history fundamentally different in kind from the sciences. It is concluded that, in each case, the case for separatism fows from the pervasive assumption that any body of knowledge which might rightly be called a science can be recognised by its search for general laws of nature. As history does not seem to share this aim, it is therefore considered to be knowledge of a fundamentally different kind. -

Harga Sewaktu Wak Jadi Sebelum

HARGA SEWAKTU WAKTU BISA BERUBAH, HARGA TERBARU DAN STOCK JADI SEBELUM ORDER SILAHKAN HUBUNGI KONTAK UNTUK CEK HARGA YANG TERTERA SUDAH FULL ISI !!!! Berikut harga HDD per tgl 14 - 02 - 2016 : PROMO BERLAKU SELAMA PERSEDIAAN MASIH ADA!!! EXTERNAL NEW MODEL my passport ultra 1tb Rp 1,040,000 NEW MODEL my passport ultra 2tb Rp 1,560,000 NEW MODEL my passport ultra 3tb Rp 2,500,000 NEW wd element 500gb Rp 735,000 1tb Rp 990,000 2tb WD my book Premium Storage 2tb Rp 1,650,000 (external 3,5") 3tb Rp 2,070,000 pakai adaptor 4tb Rp 2,700,000 6tb Rp 4,200,000 WD ELEMENT DESKTOP (NEW MODEL) 2tb 3tb Rp 1,950,000 Seagate falcon desktop (pake adaptor) 2tb Rp 1,500,000 NEW MODEL!! 3tb Rp - 4tb Rp - Hitachi touro Desk PRO 4tb seagate falcon 500gb Rp 715,000 1tb Rp 980,000 2tb Rp 1,510,000 Seagate SLIM 500gb Rp 750,000 1tb Rp 1,000,000 2tb Rp 1,550,000 1tb seagate wireless up 2tb Hitachi touro 500gb Rp 740,000 1tb Rp 930,000 Hitachi touro S 7200rpm 500gb Rp 810,000 1tb Rp 1,050,000 Transcend 500gb Anti shock 25H3 1tb Rp 1,040,000 2tb Rp 1,725,000 ADATA HD 710 750gb antishock & Waterproof 1tb Rp 1,000,000 2tb INTERNAL WD Blue 500gb Rp 710,000 1tb Rp 840,000 green 2tb Rp 1,270,000 3tb Rp 1,715,000 4tb Rp 2,400,000 5tb Rp 2,960,000 6tb Rp 3,840,000 black 500gb Rp 1,025,000 1tb Rp 1,285,000 2tb Rp 2,055,000 3tb Rp 2,680,000 4tb Rp 3,460,000 SEAGATE Internal 500gb Rp 685,000 1tb Rp 835,000 2tb Rp 1,215,000 3tb Rp 1,655,000 4tb Rp 2,370,000 Hitachi internal 500gb 1tb Toshiba internal 500gb Rp 630,000 1tb 2tb Rp 1,155,000 3tb Rp 1,585,000 untuk yang ingin -

The First Foretelling

University of New Orleans ScholarWorks@UNO University of New Orleans Theses and Dissertations Dissertations and Theses Fall 12-18-2014 The First Foretelling Cynthia M. Davidson University of New Orleans, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.uno.edu/td Part of the Fiction Commons Recommended Citation Davidson, Cynthia M., "The First Foretelling" (2014). University of New Orleans Theses and Dissertations. 1911. https://scholarworks.uno.edu/td/1911 This Thesis is protected by copyright and/or related rights. It has been brought to you by ScholarWorks@UNO with permission from the rights-holder(s). You are free to use this Thesis in any way that is permitted by the copyright and related rights legislation that applies to your use. For other uses you need to obtain permission from the rights- holder(s) directly, unless additional rights are indicated by a Creative Commons license in the record and/or on the work itself. This Thesis has been accepted for inclusion in University of New Orleans Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@UNO. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The First Foretelling A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the University of New Orleans in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Fine Arts in Film, Theater, and Communication Arts Concentration in Creative Writing - Fiction by Cynthia M Davidson B.G.S. Southeastern Louisiana University 2011 December, 2014 Copyright 2014, Cy Davidson ii Acknowledgements Dedicated to… James, for tolerating my time away and loving me though all of it.