The Story of Sue the T-Rex and Controversy Over Access to Fossils

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Illinois Fossils Doc 2005

State of Illinois Illinois Department of Natural Resources Illinois Fossils Illinois Department of Natural Resources he Illinois Fossils activity book from the Illinois Department of Natural Resources’ (IDNR) Division of Education is designed to supplement your curriculum in a vari- ety of ways. The information and activities contained in this publication are targeted toT grades four through eight. The Illinois Fossils resources trunk and lessons can help you T teach about fossils, too. You will find these and other supplemental items through the Web page at https://www2.illinois.gov/dnr/education/Pages/default.aspx. Contact the IDNR Division of Education at 217-524-4126 or [email protected] for more information. Collinson, Charles. 2002. Guide for beginning fossil hunters. Illinois State Geological Survey, Champaign, Illinois. Geoscience Education Series 15. 49 pp. Frankie, Wayne. 2004. Guide to rocks and minerals of Illinois. Illinois State Geological Survey, Champaign, Illinois. Geoscience Education Series 16. 71 pp. Killey, Myrna M. 1998. Illinois’ ice age legacy. Illinois State Geological Survey, Champaign, Illinois. Geoscience Education Series 14. 67 pp. Much of the material in this book is adapted from the Illinois State Geological Survey’s (ISGS) Guide for Beginning Fossil Hunters. Special thanks are given to Charles Collinson, former ISGS geologist, for the use of his fossil illustrations. Equal opportunity to participate in programs of the Illinois Department of Natural Resources (IDNR) and those funded by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service and other agencies is available to all individuals regardless of race, sex, national origin, disability, age, reli-gion or other non-merit factors. -

Fossil Collecting Areas in Iowa

FOSSIL COLLECTING AREAS IN IOWA The following list, although far from compete, includes a few of the better fossil collecting areas in Iowa. 1. Rockford, Floyd County (¼ mile south and ¼ mile west of the Rockford Brick and Tile Company pit, on county road “D”). Well preserved brachiopods, gastropods, and corals are most abundant in the yellowish shales that overlie the blue-gray beds. The fossils occurring here are known as the Hackberry fauna and have been described by C.L. and M.A. Fenton in a book entitled, “The Hackberry State of the Upper Devonian,” published by the MacMillan Company in 1924. 2. Bird Hill, Cerro Gordo County This is near the center of the north line of section 24, T 95N, R.19W, about 3½ miles west and ¼ mile south of the Rockford Brick and Tile Company Plant. The Hackberry fauna can be collected here also. 3. Elgin-Clermont area, Fayette County In the Elgin Member of the Maquoketa Formation large trilobites and both straight and coiled cephalopods are found. Fragments of trilobites are common, but whole specimens are rare. Road cuts along the new highway between Clermont and Elgin, the dry stream bed along county road “Y” east of Clermont, and the high-road cuts along the Turkey River southeast of Elgin are all good collecting sites. References for this area are: (1) Slocum, A.W., “Trilobites from the Maquoketa Beds of Fayette County, Iowa,” Iowa Geological Survey Annual Report, Volume 25; (2) Walter, O.T., “Trilobites of Iowa and some Related Paleozoic Forms,” Iowa Geological Survey Annual Report, Volume 31; (3) Ladd, H.S., “Stratigraphy and Paleontology of the Maquoketa Shale of Iowa,” Iowa Geological Survey Annual Report, Volume 34. -

Theropod Teeth from the Upper Maastrichtian Hell Creek Formation “Sue” Quarry: New Morphotypes and Faunal Comparisons

Theropod teeth from the upper Maastrichtian Hell Creek Formation “Sue” Quarry: New morphotypes and faunal comparisons TERRY A. GATES, LINDSAY E. ZANNO, and PETER J. MAKOVICKY Gates, T.A., Zanno, L.E., and Makovicky, P.J. 2015. Theropod teeth from the upper Maastrichtian Hell Creek Formation “Sue” Quarry: New morphotypes and faunal comparisons. Acta Palaeontologica Polonica 60 (1): 131–139. Isolated teeth from vertebrate microfossil localities often provide unique information on the biodiversity of ancient ecosystems that might otherwise remain unrecognized. Microfossil sampling is a particularly valuable tool for doc- umenting taxa that are poorly represented in macrofossil surveys due to small body size, fragile skeletal structure, or relatively low ecosystem abundance. Because biodiversity patterns in the late Maastrichtian of North American are the primary data for a broad array of studies regarding non-avian dinosaur extinction in the terminal Cretaceous, intensive sampling on multiple scales is critical to understanding the nature of this event. We address theropod biodiversity in the Maastrichtian by examining teeth collected from the Hell Creek Formation locality that yielded FMNH PR 2081 (the Tyrannosaurus rex specimen “Sue”). Eight morphotypes (three previously undocumented) are identified in the sample, representing Tyrannosauridae, Dromaeosauridae, Troodontidae, and Avialae. Noticeably absent are teeth attributed to the morphotypes Richardoestesia and Paronychodon. Morphometric comparison to dromaeosaurid teeth from multiple Hell Creek and Lance formations microsites reveals two unique dromaeosaurid morphotypes bearing finer distal denticles than present on teeth of similar size, and also differences in crown shape in at least one of these. These findings suggest more dromaeosaurid taxa, and a higher Maastrichtian biodiversity, than previously appreciated. -

T. Rex 'Trix' Reviving a Fossil

T. Rex ‘Trix’ Reviving a fossil Teacher’s guide Dear teacher, Here’s the educator’s guide for the 3D printing activity “Print your own T.rex”. This document contains information about: - The structure of the activity - The prints - Background information on T. rex Trix of Naturalis - Assembly Instructions - References to necessary resources and helpful tips Plan your lesson according to your own best judgment. Work on another activity, while the 3D printer is running. In total, the students will be working on this lesson effectively for about a day part. For questions about printing, please contact your local technical support team via this link: https://ultimaker.com/contact Have fun printing and investigating! Kind regards, Matthijs Graner [email protected] Educational developer Naturalis 1 Lesson plan Short description of the activity During the activity, you will print different bones of Trix - one at a time. Students will wonder about what will come out of the printer. They will think about what it is, where it came from and where it belongs. They will think about the form and function and will be able to do calculations on steps and scale. Eventually, your students will put together Trix into a model (scale 1:15) for the classroom. Target audience Upper primary education (grade 4-7). Objectives - Students learn about the form and function of dinosaur bones. - Students make connections between the bones of contemporary animals and their own skeletons. - Students are able to describe broadly how T. rex lived. - Students learn how scientists research dinosaur fossils. - Students learn about the possibilities of 3D printing. -

The Battle for Sue: a Controversy Over Commercial Collecting, Fossil

The Battle for Sue: A Controversy Over Commercial Collecting, Fossil Ownership Rights and its Effects on Museums Adrienne Stroup MUS 503: Intro to Museum Studies 13 December 2011 Should commercial fossil dealing be legal? Many museums rely on dealers for specimens because they do not have the resources to fund professional excavations conducted by paleontologists. On the contrary, many members of the scientific community believe commercial fossil hunting by amateurs hurts the integrity of paleontology, and in turn negatively affects museums. This debate, along with issues surrounding the ownership rights of fossil resources, is not a new one, but it came to the attention of the media when a Tyrannosaurus rex dubbed “Sue” was discovered in South Dakota in 1990. Flashing back 67 million years ago, western South Dakota was once the coast of an inland sea that divided the North American continent in two. The climate was humid and swampy, with dense vegetation, much like the southeastern United States is today (Fiffer 12). The seven-ton Tyrannosaurus dominated the landscape as the top predator of the Cretaceous Period. Standing over thirteen feet tall at the hips, up to twenty feet tall when standing completely upright, and forty-one feet long, Sue would have been a formidable opponent (Reedstrom). Her fossilized remains portray an animal that led a violent and difficult life, with evidence of a healed leg fracture, and other injuries. A tooth fragment embedded in her rib and puncture wounds in her jaw and eye socket suggest fights with other Tyrannosaurs, leading to her possible cause of death, a fatal skull-crushing bite (Monastersky, “Sake of Sue”). -

Mary Anning of Lyme Regis: 19Th Century Pioneer in British Palaeontology

Headwaters Volume 26 Article 14 2009 Mary Anning of Lyme Regis: 19th Century Pioneer in British Palaeontology Larry E. Davis College of St. Benedict / St. John's University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.csbsju.edu/headwaters Part of the Geology Commons, and the Paleontology Commons Recommended Citation Davis, Larry E. (2009) "Mary Anning of Lyme Regis: 19th Century Pioneer in British Palaeontology," Headwaters: Vol. 26, 96-126. Available at: https://digitalcommons.csbsju.edu/headwaters/vol26/iss1/14 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by DigitalCommons@CSB/SJU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Headwaters by an authorized editor of DigitalCommons@CSB/SJU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. LARRY E. DAVIS Mary Anning of Lyme Regis 19th Century Pioneer in British Palaeontology Ludwig Leichhardt, a 19th century German explorer noted in a letter, “… we had the pleasure of making the acquaintance of the Princess of Palaeontology, Miss Anning. She is a strong, energetic spinster of about 28 years of age, tanned and masculine in expression …” (Aurousseau, 1968). Gideon Mantell, a 19th century British palaeontologist, made a less flattering remark when he wrote in his journal, “… sallied out in quest of Mary An- ning, the geological lioness … we found her in a little dirt shop with hundreds of specimens piled around her in the greatest disorder. She, the presiding Deity, a prim, pedantic vinegar looking female; shred, and rather satirical in her conversation” (Curwin, 1940). Who was Mary Anning, this Princess of Palaeontology and Geological Lioness (Fig. -

The Paleontology Synthesis Project and Establishing a Framework for Managing National Park Service Paleontological Resource Archives and Data

Lucas, S.G. and Sullivan, R.M., eds., 2018, Fossil Record 6. New Mexico Museum of Natural History and Science Bulletin 79. 589 THE PALEONTOLOGY SYNTHESIS PROJECT AND ESTABLISHING A FRAMEWORK FOR MANAGING NATIONAL PARK SERVICE PALEONTOLOGICAL RESOURCE ARCHIVES AND DATA VINCENT L. SANTUCCI1, JUSTIN S. TWEET2 and TIMOTHY B. CONNORS3 1National Park Service, Geologic Resources Division, 1849 “C” Street, NW, Washington, D.C. 20240, [email protected]; 2National Park Service, 9149 79th Street S., Cottage Grove, MN 55016, [email protected]; 3National Park Service, Geologic Resources Division, 12795 W. Alameda Parkway, Lakewood, CO 80225, [email protected] Abstract—The National Park Service Paleontology Program maintains an extensive collection of digital and hard copy documents, publications, photographs and other archives associated with the paleontological resources documented in 268 parks. The organization and preservation of the NPS paleontology archives has been the focus of intensive data management activities by a small and dedicated team of NPS staff. The data preservation strategy complemented the NPS servicewide inventories for paleontological resources. The first phase of the data management, referred to as the NPS Paleontology Synthesis Project, compiled servicewide paleontological resource data pertaining to geologic time, taxonomy, museum repositories, holotype fossil specimens, and numerous other topics. In 2015, the second phase of data management was implemented with the creation and organization of a multi-faceted digital data system known as the NPS Paleontology Archives and NPS Paleontology Library. Two components of the NPS Paleontology Archives were designed for the preservation of both park specific and servicewide paleontological resource archives and data. A third component, the NPS Paleontology Library, is a repository for electronic copies of geology and paleontology publications, reports, and other media. -

Fossil Collecting in Ohio

No. 17 OHIOGeoFacts DEPARTMENT OF NATURAL RESOURCES • DIVISION OF GEOLOGICAL SURVEY FOSSIL COLLECTING IN OHIO Hobbyists have long known about Ohio’s great abundance and WHERE FOSSILS ARE FOUND IN OHIO diversity of fossils. Many world-famous paleontologists—geologists who study fossils—began their careers as youngsters collecting fossils Ordovician rocks in Ohio are world famous for in their native Ohio. Fossils from Ohio are important constituents the abundance, variety, and excellent preserva- of museum collections throughout the United States and Europe. tion of the fossils they contain. The limestones and shales exposed in almost every road cut or WHY OHIO HAS FOSSILS stream bed in southwestern Ohio, southeastern Indiana, and north-central Kentucky provide The area that is now Ohio was not always dry land as it is today. the opportunity to collect a bonanza of fossils. Approximately 510 million years ago (m.y.a.), Ohio was south of the Among the more abundant types of fossils col- Equator. As the North American Plate moved to its current position ORDOVICIAN lected from Ordovician rocks are brachiopods, 508–438 m.y.a. through the process of plate tectonics, tropical to subtropical seas bryozoans, gastropods, and trilobites. repeatedly transgressed over the plate. It is because of those warm Silurian rocks of western Ohio are not known seas that Ohio has the abundant fossils that people collect today. for their fossils. When the limestones and shales The seas that covered Ohio during the Ordovician, Silurian, and were fi rst deposited they were quite fossilifer- most of the Devonian Periods of the Paleozoic Era were the site of ous. -

Princeton Alumni Weekly

00paw0206_cover3NOBOX_00paw0707_Cov74 1/22/13 12:26 PM Page 1 Arts district approved Princeton Blairstown soon to be on its own Alumni College access for Weekly low-income students LIVES LIVED AND LOST: An appreciation ! Nicholas deB. Katzenbach ’43 February 6, 2013 • paw.princeton.edu During the month of February all members save big time on everyone’s favorite: t-shirts! Champion and College Kids brand crewneck tees are marked to $11.99! All League brand tees and Champion brand v-neck tees are reduced to $17.99! Stock up for the spring time, deals like this won’t last! SELECT T-SHIRTS FOR MEMBERS ONLY $11.99 - $17.99 3KRWR3ULQFHWRQ8QLYHUVLW\2I¿FHRI&RPPXQLFDWLRQV 36 UNIVERSITY PLACE CHECK US 116 NASSAU STREET OUT ON 800.624.4236 FACEBOOK! WWW.PUSTORE.COM February 2013 PAW Ad.indd 3 1/7/2013 4:16:20 PM 01paw0206_TOCrev1_01paw0512_TOC 1/22/13 11:36 AM Page 1 Franklin A. Dorman ’48, page 24 Princeton Alumni Weekly An editorially independent magazine by alumni for alumni since 1900 FEBRUARY 6, 2013 VOLUME 113 NUMBER 7 President’s Page 2 Inbox 5 From the Editor 6 Perspective 11 Unwelcome advances: A woman’s COURTESY life in the city JENNIFER By Chloe S. Angyal ’09 JONES Campus Notebook 12 Arts district wins approval • Committee to study college access for low-income Lives lived and lost: An appreciation 24 students • Faculty divestment petition PAW remembers alumni whose lives ended in 2012, including: • Cost of journals soars • For Mid east, a “2.5-state solution” • Blairs town, Charles Rosen ’48 *51 • Klaus Goldschlag *49 • University to cut ties • IDEAS: Rise of the troubled euro • Platinum out, iron Nicholas deB. -

The Greatest Challenge to 21St Century Paleontology: When Commercialization of Fossils Threatens the Science

Palaeontologia Electronica http://palaeo-electronica.org The greatest challenge to 21st century paleontology: When commercialization of fossils threatens the science Kenshu Shimada, Philip J. Currie, Eric Scott, and Stuart S. Sumida As we proceed into the 21st century, the sci- responses to geological and climatic factors. Pale- ence of paleontology has achieved a remarkable ontology presently enjoys a new “Golden Age,” prominence and popularity, providing increasingly progressing by leaps while also serving, as always, detailed perspective on critical biological and geo- to inspire young minds to explore science and the logical processes. Spectacular new discoveries natural world. excite the imagination and spur new investigations, Yet at the outset of the millennium, three inter- while more abundant fossils studied using new connected, troubling challenges confront paleontol- techniques enable more precise interpretations of ogists: 1) a shrinking job market, 2) diminishing diversity, variation, changes through time, and funding sources, and 3) heightened commercial- Editor’s note: The commercial collection and sale of fossils, as well as the still developing regulations involving collection of fossils on public lands, have emerged as one of the most contentious issues in pale- ontology. These issues pit not only professional paleontologists and commercial collectors against each other, but have produced rifts within the paleontological community. Here Shimada and his co-authors vig- orously present a position supported by many vertebrate paleontologists. I repeat a call in an earlier com- mentary (Plotnick, 2011; palaeo-electronica.org/2011_1/commentary/mainstream.htm) for additional contributions that would discuss these issues that are so crucial to our field. Please send directly to Roy E. -

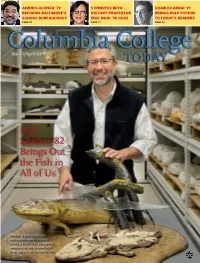

Neil Shubin '82 Brings out the Fish in All of Us

ANDRES ALONSO ’79 5 MINUTES WITH … CHARLES ARDAI ’91 REFORMS BALTIMORE’S HISTORY PROFESSOR BRINGS PULP FICTION SCHOOL BUREAUCRACY MAE NGAI ’98 GSAS TO TODAY’S READERS PAGE 22 PAGE 11 PAGE 24 Columbia College March/April 2011 TODAY Neil Shubin ’82 Brings Out the Fish in All of Us Shubin, a paleontologist and evolutionary biologist, co-led a team that discovered evidence of the pivotal shift from aquatic to terrestrial life. ust another J membership perk. Meet. Dine. Entertain. Join the Columbia Club and access state-of-the-art meeting rooms for your conferences and events. For more information or to apply, visit www.columbiaclub.org or call (212) 719-0380. The Columbia University Club of New York in residence at 15 West 43 St. New York, N Y 10036 Columbia’s SocialIntellectualCulturalRecreationalProfessional Resource in Midtown. Columbia College Today Contents 22 12 24 7 56 18 COVER STORY ALUMNI NEWS DEPARTMENTS G O FISH 27 O BITUARIES 2 LETTERS TO THE 12 Paleontologist and evolutionary biologist Neil Shubin 27 Joseph D. Coffee Jr. ’41 EDITOR ’82 brings out the fish in all of us. 28 Garland E. Wood ’65 3 ITHIN THE AMILY By Nathalie Alonso ’08 W F 30 B OOKSHEL F 4 AROUND THE QUADS FEATURES Featured: Adam Gidwitz ’04 4 turns classic folklore on its Northwest Corner Building Opens COLUMBIA FORUM ear with his new children’s 18 book, A Tale Dark & Grimm. 5 Rose, Jones Join In an excerpt from his book How Soccer Explains the College Senior Staff World: An Unlikely Theory of Globalization, Franklin 32 LASS OTES 6 Creed To Deliver Foer ’96 explains how one soccer club’s destiny was C N A LUMNI PRO F ILES Class Day Address shaped by European anti-Semitism. -

A Census of Dinosaur Fossils Recovered from the Hell Creek and Lance Formations (Maastrichtian)

The Journal of Paleontological Sciences: JPS.C.2019.01 1 TAKING COUNT: A Census of Dinosaur Fossils Recovered From the Hell Creek and Lance Formations (Maastrichtian). ______________________________________________________________________________________ Walter W. Stein- President, PaleoAdventures 1432 Mill St.. Belle Fourche, SD 57717. [email protected] 605-210-1275 ABSTRACT: A census of Hell Creek and Lance Formation dinosaur remains was conducted from April, 2017 through February of 2018. Online databases were reviewed and curators and collections managers interviewed in an effort to determine how much material had been collected over the past 130+ years of exploration. The results of this new census has led to numerous observations regarding the quantity, quality, and locations of the total collection, as well as ancillary data on the faunal diversity and density of Late Cretaceous dinosaur populations. By reviewing the available data, it was also possible to make general observations regarding the current state of certain exploration programs, the nature of collection bias present in those collections and the availability of today's online databases. A total of 653 distinct, associated and/or articulated remains (skulls and partial skeletons) were located. Ceratopsid skulls and partial skeletons (mostly identified as Triceratops) were the most numerous, tallying over 335+ specimens. Hadrosaurids (Edmontosaurus) were second with at least 149 associated and/or articulated remains. Tyrannosaurids (Tyrannosaurus and Nanotyrannus) were third with a total of 71 associated and/or articulated specimens currently known to exist. Basal ornithopods (Thescelosaurus) were also well represented by at least 42 known associated and/or articulated remains. The remaining associated and/or articulated specimens, included pachycephalosaurids (18), ankylosaurids (6) nodosaurids (6), ornithomimids (13), oviraptorosaurids (9), dromaeosaurids (1) and troodontids (1).