Fishing for Answers

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Nothing in Biology Makes Sense Except in the Light of Evolution: Pattern, Pro Cess, and the Evidence

Nothing in Biology Makes Sense Except in the Light of Evolution: Pattern, Pro cess, and the Evidence Jonathan B. Losos Evolutionary biology is unusual: unlike any other science, evolution- ary biologists study a phenomenon that some people do not think exists. Consider chemistry, for example; it is unlikely that anyone does not believe in the existence of chemical reactions. Ditto for the laws of physics. Even within biology, no one believes that cells do not exist nor that DNA is a fraud. But public opinion polls consistently show that a majority of the American public is either unsure about or does not believe that life has evolved through time. For example, a Gallup poll taken repeatedly over the past twenty years indicates that as much as 40 percent of the population believes that the Bible is liter- ally correct. When I teach evolutionary biology, I focus on the ideas about how evolution works, rather than on the empirical record of how species have changed through time. However, for one lecture period I make an exception, and in some respects I consider this the most important lecture of the semester. Sad as I fi nd it to be, most of my students will not go on to become evolutionary biologists. Rather, they will become leaders in many diverse aspects of society: doctors, lawyers, business- people, clergy, and artists; people to whom others will look for guid- ance on matters of knowledge and science. For this reason, although I devote my course to a detailed understanding of the evolutionary pro cess, I consider it vitally important that my students understand why it is that almost all biologists fi nd the evidence that evolution has occurred— and continues to occur— to be overwhelming. -

Tiktaalik: Reconstructed at Left Tetrapod Testimony

Fa m i liar Fossils Tiktaalik fossil at right and Fossil site Tiktaalik: reconstructed at left Tetrapod Testimony IMAGINE a creature that looks like a crocodile with a neck but which also has gills like a fish! The stuff of nightmares, did you say? But it is just Tiktaalik roseae – a fish-like fossil that was introduced to the year old rocks. world on April 2006 by a team of researchers led by Neil They had a pretty Shubin, Edward Daeschler and Farish Jenkins, who clear idea about uncovered this bizarre specimen. It has been hailed as what sort of being the species that blurs the boundary between fish animal they were and the four-legged tetrapods. looking for. Tiktaalik was found on Ellesmere Island, Canada, However, success not too far from the North Pole in the Arctic Circle. It has was not been described as, “a cross between a fish and a crocodile.” immediate. It took It lived in the Devonian era lasting from 417m to 354m them five separate years ago. The name Tiktaalik is the Inuktitut word for expeditions to the freshwater fish burbot (Lota lota). The name was Canada before they suggested by Inuit elders of the area where the fossil was raised the discovered. The specific name roseae holds the clue to Tiktaalik. the name of an anonymous donor and is a tribute to the Tiktaalik was dubbed a “fishapod” by Daeschler. The person. media called it a “missing link” between fish and the Tiktaalik was a fish no doubt but a special one. Its four-legged tetrapods. -

The Fish That Crawled out of the Water

Published online 5 April 2006 | Nature | doi:10.1038/news060403-7 News The fish that crawled out of the water A newly found fossil links fish to land-lubbers. Rex Dalton A crucial fossil that shows how animals crawled out from the water, evolving from fish into land-loving animals, has been found in Canada. The creature, described today in Nature1,2, lived some 375 million years ago. Palaeontologists are calling the specimen from the Devonian a true 'missing link', as it helps to fill in a gap in our understanding of how fish developed legs for land mobility, before eventually evolving into modern animals including mankind. Several samples of the fish-like tetrapod, named Tiktaalik roseae, were “Tetrapods did not so much discovered by Edward Daeschler of the Academy of Natural Sciences in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, Neil Shubin of the University of Chicago in conquer the land, The fossilized remains of as escape from the Illinois, Farish Jenkins of Harvard University in Cambridge, Massachusetts Tiktaalik show a crocodile-like water.” and colleagues. creature with joints in its front arms. The crew found the samples in a river delta on Ellesmere Island in Arctic credit Ted Daeschler Canada; these included a near-complete front half of a fossilized skeleton of a crocodile-like creature, whose skull is some 20 centimetres long. The beast has bony scales and fins, but the front fins are on their way to becoming limbs; they have the internal skeletal structure of an arm, including elbows and wrists, but with fins instead of clear fingers. The team is still looking for more complete specimens to get a better picture of hind part of the animal. -

Center for Systematic Biology & Evolution

CENTER FOR SYSTEMATIC BIOLOGY & EVOLUTION 2008 ACTIVITY REPORT BY THE NUMBERS Research Visitors ....................... 253 Student Visitors.......................... 230 Other Visitors.......................... 1,596 TOTAL....................... 2,079 Outgoing Loans.......................... 535 Specimens/Lots Loaned........... 6,851 Information Requests .............. 1,294 FIELD WORK Botany - Uruguay Diatoms – Russia (Commander Islands, Kamchatka, Magdan) Entomology – Arizona, Colorado, Florida, Hawaii, Lesotho, Minnesota, Mississippi, Mongolia, Namibia, New Jersey, New Mexico, Ohio, Pennsylvania, South Africa, Tennessee LMSE – Zambia Ornithology – Alaska, England Vertebrate Paleontology – Canada (Nunavut Territory), Pennsylvania PROPOSALS BOTANY . Digitization of Latin American, African and other type specimens of plants at the Academy of Natural Sciences of Philadelphia, Global Plants Initiative (GPI), Mellon Foundation Award. DIATOMS . Algal Research and Ecologival Synthesis for the USGS National Water Quality Assessment (NAWQA) Program Cooperative Agreement 3. Co-PI with Don Charles (Patrick Center for Environmental Research, Phycology). Collaborative Research on Ecosystem Monitoring in the Russian Northern Far-East, Trust for Mutual Understanding Grant. CSBE Activity Report - 2008 . Diatoms of the Northcentral Pennsylvania, Pennsylvania Department of Conservation and Natural Resources, Wild Rescue Conservation Grant. Renovation and Computerization of the Diatom Herbarium at the Academy of Natural Sciences of Philadelphia, National -

Phylogeny of Basal Tetrapoda

Stuart S. Sumida Biology 342 Phylogeny of Basal Tetrapoda The group of bony fishes that gave rise to land-dwelling vertebrates and their descendants (Tetrapoda, or colloquially, “tetrapods”) was the lobe-finned fishes, or Sarcopterygii. Sarcoptrygii includes coelacanths (which retain one living form, Latimeria), lungfish, and crossopterygians. The transition from sarcopterygian fishes to stem tetrapods proceeded through a series of groups – not all of which are included here. There was no sharp and distinct transition, rather it was a continuum from very tetrapod-like fishes to very fish-like tetrapods. SARCOPTERYGII – THE LOBE-FINNED FISHES Includes •Actinista (including Coelacanths) •Dipnoi (lungfishes) •Crossopterygii Crossopterygians include “tetrapods” – 4- legged land-dwelling vertebrates. The Actinista date back to the Devonian. They have very well developed lobed-fins. There remains one livnig representative of the group, the coelacanth, Latimeria chalumnae. A lungfish The Crossopterygii include numerous representatives, the best known of which include Eusthenopteron (pictured here) and Panderichthyes. Panderichthyids were the most tetrapod-like of the sarcopterygian fishes. Panderichthyes – note the lack of dorsal fine, but retention of tail fin. Coelacanths Lungfish Rhizodontids Eusthenopteron Panderichthyes Tiktaalik Ventastega Acanthostega Ichthyostega Tulerpeton Whatcheeria Pederpes More advanced amphibians Tiktaalik roseae – a lobe-finned fish intermediate between typical sarcopterygians and basal tetrapods. Mid to Late Devonian; 375 million years old. The back end of Tiktaalik’s skull is intermediate between fishes and tetrapods. Tiktaalik is a fish with wrist bones, yet still retaining fin rays. The posture of Tiktaalik’s fin/limb is intermediate between that of fishes an tetrapods. Coelacanths Lungfish Rhizodontids Eusthenopteron Panderichthyes Tiktaalik Ventastega Acanthostega Ichthyostega Tulerpeton Whatcheeria Pederpes More advanced amphibians Reconstructions of the basal tetrapod Ventastega. -

Princeton Alumni Weekly

00paw0206_cover3NOBOX_00paw0707_Cov74 1/22/13 12:26 PM Page 1 Arts district approved Princeton Blairstown soon to be on its own Alumni College access for Weekly low-income students LIVES LIVED AND LOST: An appreciation ! Nicholas deB. Katzenbach ’43 February 6, 2013 • paw.princeton.edu During the month of February all members save big time on everyone’s favorite: t-shirts! Champion and College Kids brand crewneck tees are marked to $11.99! All League brand tees and Champion brand v-neck tees are reduced to $17.99! Stock up for the spring time, deals like this won’t last! SELECT T-SHIRTS FOR MEMBERS ONLY $11.99 - $17.99 3KRWR3ULQFHWRQ8QLYHUVLW\2I¿FHRI&RPPXQLFDWLRQV 36 UNIVERSITY PLACE CHECK US 116 NASSAU STREET OUT ON 800.624.4236 FACEBOOK! WWW.PUSTORE.COM February 2013 PAW Ad.indd 3 1/7/2013 4:16:20 PM 01paw0206_TOCrev1_01paw0512_TOC 1/22/13 11:36 AM Page 1 Franklin A. Dorman ’48, page 24 Princeton Alumni Weekly An editorially independent magazine by alumni for alumni since 1900 FEBRUARY 6, 2013 VOLUME 113 NUMBER 7 President’s Page 2 Inbox 5 From the Editor 6 Perspective 11 Unwelcome advances: A woman’s COURTESY life in the city JENNIFER By Chloe S. Angyal ’09 JONES Campus Notebook 12 Arts district wins approval • Committee to study college access for low-income Lives lived and lost: An appreciation 24 students • Faculty divestment petition PAW remembers alumni whose lives ended in 2012, including: • Cost of journals soars • For Mid east, a “2.5-state solution” • Blairs town, Charles Rosen ’48 *51 • Klaus Goldschlag *49 • University to cut ties • IDEAS: Rise of the troubled euro • Platinum out, iron Nicholas deB. -

Teacher's Guide: Tiktaalik: a Fish out of Water

Teacher’s Guide: Tiktaalik: A Fish Out of Water Recommended Grade Level: 5–8 (also applicable to grades 9–12 for students requiring significant support in learning) Suggested Time: About 50–60 minutes spread over one or more class periods, plus additional time to complete a writing assignment Goals Vocabulary Following are the big ideas that students • fossil should take away after completing this lesson: • characteristic • Transitional fossils help scientists establish • transition how living things are related • tetrapod • Physical features and behaviors may • species change over time to help living things sur- vive where they live • amphibian • evolution Key Literacy Strategies Following are the primary literacy strategies students will use to complete this activity: • Categorizing basic facts and ideas (screen 10) • Making inferences (screens 4 and 7, writing assignment 2) • Identifying and using text features (screens 4, 6, and 9) • Determining important information (screen 7, writing assignment 1) • Sequencing events (screen 9) Note: In addition to using the key literacy strategies listed above, students will use each of the strategies below to complete this lesson: • Monitoring comprehension • Synthesizing • Making predictions • Developing vocabulary • Connecting prior knowledge to new learning • Developing a topic in writing • Identifying and using text features (photographs, captions, diagrams, and/or maps) Overview Tiktaalik: A Fish Out of Water is a student-directed learning experience. However, while students are expected to work through the lesson on their own, teachers should be available to keep the lesson on track, organize groupings, facilitate discussions, answer questions, and ensure that all learning goals are met. Teacher’s Guide: Tiktaalik: A Fish Out of Water 1 The following is a summary of the lesson screens: Screen 1: Students learn that they will explore evolutionary relationships between animal groups that do not appear to be related. -

Farish A. Jenkins Jr (1940–2012) Palaeontologist, Anatomist, Explorer and Artist

COMMENT OBITUARY Farish A. Jenkins Jr (1940–2012) Palaeontologist, anatomist, explorer and artist. ith a rifle strapped to his back nearly a century’s worth of speculation about a serendipitous expansion of his research each summer, a scalpel in his functional anatomy that had been based on programme to include other tetrapod hand each autumn and the eyes fossils alone. groups. In the 1990s and 2000s, Jenkins used Wof an artist throughout the year, Farish Jenkins’s research output was as systematic the same approach to open up the Triassic Jenkins Jr seamlessly blended expeditionary as his military training had been. During the rocks of Greenland and the Devonian palaeontology with experimental sediments of Arctic Canada to anatomy to establish how animals palaeontological discovery. He evolved to walk, run, jump and fly. uncovered haramiyids (some of the Jenkins, who died of com- earliest mammals) in the Triassic plications from pneumonia on rocks and Tiktaalik (a genus of lobe- 11 November, was raised in Rye, finned fish) in the Devonian ones. New York. As a child, he showed Jenkins was president of the no obvious draw towards a life of Society of Vertebrate Paleontology science and exploration. But two in 1981–82, and he received its experiences transformed him. While Romer-Simpson Medal for life- S. KREITER/BOSTON GLOBE VIA GETTY VIA GETTY GLOBE S. KREITER/BOSTON studying philosophy at Princeton time achievement in 2009. He will University in New Jersey in the early be remembered by generations 1960s, Jenkins spent a summer as an of undergraduates, graduate and undergraduate assistant to Glenn medical students and assistant Lowell Jepsen. -

Qnas with Neil Shubin

QNAS QNAS QnAs with Neil Shubin Prashant Nair “ ” Science Writer with a four wheel drive, such as animals that walk on land using limbs. PNAS: Your 2006 description of Tiktaalik furnished a view of the animal’sfrontend. From the rust-brown sediments of long-dried their saga of evolution in his PNAS Inau- Why did it take so long to disinter and de- streams that once rumbled through the rug- gural Article (1). scribe the pelvic appendage? ’ PNAS: Your discovery of Tiktaalik’spelvic ged terrain of Canada s Ellesmere Island, a Shubin: We had collected two blocks of appendage addresses a longstanding conun- team of paleontologists unearthed in 2004 specimens in 2004, one of which contained fi drum in the evolution of locomotion in the fossils of a 375 million-year-old species of sh the front end of the Tiktaalik reference spec- animal kingdom: the contrast between move- that may have nearly crossed an evolutionary imen described in the 2006 papers. We did Tiktaalik roseae ment using fins in the front of the body and Rubicon. Named ,thenow- not look at the second block right away, movement using appendages in the front and extinct animal has come to represent an in- mainly because it didn’tseemtocontain back. Can you explain the evolutionary sig- termediate link between fish and amphibians, much bone and because we had collected nificance of the distinction between these its features likely enabling a leap from water it for the sake of completeness. It took us forms of locomotion? to land. Led by National Academy of Sciences a number of years to prepare, study, and Shubin: Limbed vertebrates, or terapods, member Neil Shubin, a paleontologist at the draw conclusions about this pelvic structure, have four appendages, two in the front and University of Chicago, the team described the found in the second block, partly because the two in the back. -

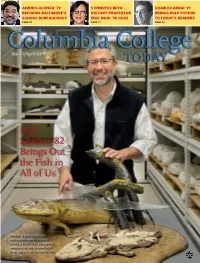

Neil Shubin '82 Brings out the Fish in All of Us

ANDRES ALONSO ’79 5 MINUTES WITH … CHARLES ARDAI ’91 REFORMS BALTIMORE’S HISTORY PROFESSOR BRINGS PULP FICTION SCHOOL BUREAUCRACY MAE NGAI ’98 GSAS TO TODAY’S READERS PAGE 22 PAGE 11 PAGE 24 Columbia College March/April 2011 TODAY Neil Shubin ’82 Brings Out the Fish in All of Us Shubin, a paleontologist and evolutionary biologist, co-led a team that discovered evidence of the pivotal shift from aquatic to terrestrial life. ust another J membership perk. Meet. Dine. Entertain. Join the Columbia Club and access state-of-the-art meeting rooms for your conferences and events. For more information or to apply, visit www.columbiaclub.org or call (212) 719-0380. The Columbia University Club of New York in residence at 15 West 43 St. New York, N Y 10036 Columbia’s SocialIntellectualCulturalRecreationalProfessional Resource in Midtown. Columbia College Today Contents 22 12 24 7 56 18 COVER STORY ALUMNI NEWS DEPARTMENTS G O FISH 27 O BITUARIES 2 LETTERS TO THE 12 Paleontologist and evolutionary biologist Neil Shubin 27 Joseph D. Coffee Jr. ’41 EDITOR ’82 brings out the fish in all of us. 28 Garland E. Wood ’65 3 ITHIN THE AMILY By Nathalie Alonso ’08 W F 30 B OOKSHEL F 4 AROUND THE QUADS FEATURES Featured: Adam Gidwitz ’04 4 turns classic folklore on its Northwest Corner Building Opens COLUMBIA FORUM ear with his new children’s 18 book, A Tale Dark & Grimm. 5 Rose, Jones Join In an excerpt from his book How Soccer Explains the College Senior Staff World: An Unlikely Theory of Globalization, Franklin 32 LASS OTES 6 Creed To Deliver Foer ’96 explains how one soccer club’s destiny was C N A LUMNI PRO F ILES Class Day Address shaped by European anti-Semitism. -

Your Inner Fish : a Journey Into the 3.5-Billion-Year History of the Human Body / by Neil Shubin.—1St Ed

EPILOGUE As a parent of two young children, I find myself spending a lot of time lately in zoos, museums, and aquaria. Being a visitor is a strange experience, because I’ve been involved with these places for decades, working in museum collections and even helping to prepare exhibits on occasion. During family trips, I’ve come to realize how much my vocation can make me numb to the beauty and sublime complexity of our world and our bodies. I teach and write about millions of years of history and about bizarre ancient worlds, and usually my interest is detached and analytic. Now I’m experiencing science with my children—in the kinds of places where I discovered my love for it in the first place. One special moment happened recently with my son at the Museum of Science and Industry in Chicago. We’ve gone there regularly over the past three years because of his love of trains and the fact that there is a huge model railroad smack in the center of the place. I’ve spent countless hours at that one exhibit tracing model locomotives on their little trek from Chicago to Seattle. After a number of weekly visits 263 to this shrine for the train-obsessed, Nathaniel and I walked to corners of the museum we had failed to visit during our train-watching ventures or occasional forays to the full-size tractors and planes. In the back of the museum, in the Henry Crown Space Center, model planets hang from the ceiling and space suits lie in cases together with other memorabilia of the space program of the 1960s and 1970s. -

Scientists Speak 19.2 NEIL SHUBIN: When I Look at My Fellow Humans, I

Scientists Speak 19.2 NEIL SHUBIN: When I look at my fellow humans, I see ghosts of animals past. Glimpses of an epic story that is hidden inside us all. My name is Neil Shubin. As a scientist, I look at human bodies different from most people. The way we grip with our hands, we can thank our primate ancestors for that. How we hear so many sounds that dates back to creatures the size of a shrew. And the further back we go, the stranger it gets. To reveal why we look the way we do, we'll travel through the distant reaches of our family tree and meet an unusual cast of characters. The ancestors that shaped your body. The family you never knew you had. From the badlands of Ethiopia! “She's beautiful.” To the shores of Nova Scotia. “This is the spot.” We'll search for clues that lie buried in rock. “His eyes are like globes and he is like,” ‘I found it! I found it!’ And in search for answers written in our DNA. “I think it gives us a glimpse into the brain of our ancestors,” “I mean I find that mind-blowing.” The adventure begins with a search for some of our most elusive relatives. Fish that crawled onto land hundreds of millions of years ago. From our necks and lungs, to our limbs and hands, we owe a lot to these intrepid pioneers. So if you really want to see why you're built the way you are, it's time to meet your inner fish.