'We Swam Before We Breathed Or Walked': Able-Bodied

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Nothing in Biology Makes Sense Except in the Light of Evolution: Pattern, Pro Cess, and the Evidence

Nothing in Biology Makes Sense Except in the Light of Evolution: Pattern, Pro cess, and the Evidence Jonathan B. Losos Evolutionary biology is unusual: unlike any other science, evolution- ary biologists study a phenomenon that some people do not think exists. Consider chemistry, for example; it is unlikely that anyone does not believe in the existence of chemical reactions. Ditto for the laws of physics. Even within biology, no one believes that cells do not exist nor that DNA is a fraud. But public opinion polls consistently show that a majority of the American public is either unsure about or does not believe that life has evolved through time. For example, a Gallup poll taken repeatedly over the past twenty years indicates that as much as 40 percent of the population believes that the Bible is liter- ally correct. When I teach evolutionary biology, I focus on the ideas about how evolution works, rather than on the empirical record of how species have changed through time. However, for one lecture period I make an exception, and in some respects I consider this the most important lecture of the semester. Sad as I fi nd it to be, most of my students will not go on to become evolutionary biologists. Rather, they will become leaders in many diverse aspects of society: doctors, lawyers, business- people, clergy, and artists; people to whom others will look for guid- ance on matters of knowledge and science. For this reason, although I devote my course to a detailed understanding of the evolutionary pro cess, I consider it vitally important that my students understand why it is that almost all biologists fi nd the evidence that evolution has occurred— and continues to occur— to be overwhelming. -

The Fish That Crawled out of the Water

Published online 5 April 2006 | Nature | doi:10.1038/news060403-7 News The fish that crawled out of the water A newly found fossil links fish to land-lubbers. Rex Dalton A crucial fossil that shows how animals crawled out from the water, evolving from fish into land-loving animals, has been found in Canada. The creature, described today in Nature1,2, lived some 375 million years ago. Palaeontologists are calling the specimen from the Devonian a true 'missing link', as it helps to fill in a gap in our understanding of how fish developed legs for land mobility, before eventually evolving into modern animals including mankind. Several samples of the fish-like tetrapod, named Tiktaalik roseae, were “Tetrapods did not so much discovered by Edward Daeschler of the Academy of Natural Sciences in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, Neil Shubin of the University of Chicago in conquer the land, The fossilized remains of as escape from the Illinois, Farish Jenkins of Harvard University in Cambridge, Massachusetts Tiktaalik show a crocodile-like water.” and colleagues. creature with joints in its front arms. The crew found the samples in a river delta on Ellesmere Island in Arctic credit Ted Daeschler Canada; these included a near-complete front half of a fossilized skeleton of a crocodile-like creature, whose skull is some 20 centimetres long. The beast has bony scales and fins, but the front fins are on their way to becoming limbs; they have the internal skeletal structure of an arm, including elbows and wrists, but with fins instead of clear fingers. The team is still looking for more complete specimens to get a better picture of hind part of the animal. -

Farish A. Jenkins Jr (1940–2012) Palaeontologist, Anatomist, Explorer and Artist

COMMENT OBITUARY Farish A. Jenkins Jr (1940–2012) Palaeontologist, anatomist, explorer and artist. ith a rifle strapped to his back nearly a century’s worth of speculation about a serendipitous expansion of his research each summer, a scalpel in his functional anatomy that had been based on programme to include other tetrapod hand each autumn and the eyes fossils alone. groups. In the 1990s and 2000s, Jenkins used Wof an artist throughout the year, Farish Jenkins’s research output was as systematic the same approach to open up the Triassic Jenkins Jr seamlessly blended expeditionary as his military training had been. During the rocks of Greenland and the Devonian palaeontology with experimental sediments of Arctic Canada to anatomy to establish how animals palaeontological discovery. He evolved to walk, run, jump and fly. uncovered haramiyids (some of the Jenkins, who died of com- earliest mammals) in the Triassic plications from pneumonia on rocks and Tiktaalik (a genus of lobe- 11 November, was raised in Rye, finned fish) in the Devonian ones. New York. As a child, he showed Jenkins was president of the no obvious draw towards a life of Society of Vertebrate Paleontology science and exploration. But two in 1981–82, and he received its experiences transformed him. While Romer-Simpson Medal for life- S. KREITER/BOSTON GLOBE VIA GETTY VIA GETTY GLOBE S. KREITER/BOSTON studying philosophy at Princeton time achievement in 2009. He will University in New Jersey in the early be remembered by generations 1960s, Jenkins spent a summer as an of undergraduates, graduate and undergraduate assistant to Glenn medical students and assistant Lowell Jepsen. -

Qnas with Neil Shubin

QNAS QNAS QnAs with Neil Shubin Prashant Nair “ ” Science Writer with a four wheel drive, such as animals that walk on land using limbs. PNAS: Your 2006 description of Tiktaalik furnished a view of the animal’sfrontend. From the rust-brown sediments of long-dried their saga of evolution in his PNAS Inau- Why did it take so long to disinter and de- streams that once rumbled through the rug- gural Article (1). scribe the pelvic appendage? ’ PNAS: Your discovery of Tiktaalik’spelvic ged terrain of Canada s Ellesmere Island, a Shubin: We had collected two blocks of appendage addresses a longstanding conun- team of paleontologists unearthed in 2004 specimens in 2004, one of which contained fi drum in the evolution of locomotion in the fossils of a 375 million-year-old species of sh the front end of the Tiktaalik reference spec- animal kingdom: the contrast between move- that may have nearly crossed an evolutionary imen described in the 2006 papers. We did Tiktaalik roseae ment using fins in the front of the body and Rubicon. Named ,thenow- not look at the second block right away, movement using appendages in the front and extinct animal has come to represent an in- mainly because it didn’tseemtocontain back. Can you explain the evolutionary sig- termediate link between fish and amphibians, much bone and because we had collected nificance of the distinction between these its features likely enabling a leap from water it for the sake of completeness. It took us forms of locomotion? to land. Led by National Academy of Sciences a number of years to prepare, study, and Shubin: Limbed vertebrates, or terapods, member Neil Shubin, a paleontologist at the draw conclusions about this pelvic structure, have four appendages, two in the front and University of Chicago, the team described the found in the second block, partly because the two in the back. -

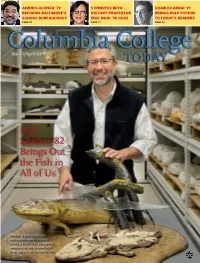

Neil Shubin '82 Brings out the Fish in All of Us

ANDRES ALONSO ’79 5 MINUTES WITH … CHARLES ARDAI ’91 REFORMS BALTIMORE’S HISTORY PROFESSOR BRINGS PULP FICTION SCHOOL BUREAUCRACY MAE NGAI ’98 GSAS TO TODAY’S READERS PAGE 22 PAGE 11 PAGE 24 Columbia College March/April 2011 TODAY Neil Shubin ’82 Brings Out the Fish in All of Us Shubin, a paleontologist and evolutionary biologist, co-led a team that discovered evidence of the pivotal shift from aquatic to terrestrial life. ust another J membership perk. Meet. Dine. Entertain. Join the Columbia Club and access state-of-the-art meeting rooms for your conferences and events. For more information or to apply, visit www.columbiaclub.org or call (212) 719-0380. The Columbia University Club of New York in residence at 15 West 43 St. New York, N Y 10036 Columbia’s SocialIntellectualCulturalRecreationalProfessional Resource in Midtown. Columbia College Today Contents 22 12 24 7 56 18 COVER STORY ALUMNI NEWS DEPARTMENTS G O FISH 27 O BITUARIES 2 LETTERS TO THE 12 Paleontologist and evolutionary biologist Neil Shubin 27 Joseph D. Coffee Jr. ’41 EDITOR ’82 brings out the fish in all of us. 28 Garland E. Wood ’65 3 ITHIN THE AMILY By Nathalie Alonso ’08 W F 30 B OOKSHEL F 4 AROUND THE QUADS FEATURES Featured: Adam Gidwitz ’04 4 turns classic folklore on its Northwest Corner Building Opens COLUMBIA FORUM ear with his new children’s 18 book, A Tale Dark & Grimm. 5 Rose, Jones Join In an excerpt from his book How Soccer Explains the College Senior Staff World: An Unlikely Theory of Globalization, Franklin 32 LASS OTES 6 Creed To Deliver Foer ’96 explains how one soccer club’s destiny was C N A LUMNI PRO F ILES Class Day Address shaped by European anti-Semitism. -

Your Inner Fish : a Journey Into the 3.5-Billion-Year History of the Human Body / by Neil Shubin.—1St Ed

EPILOGUE As a parent of two young children, I find myself spending a lot of time lately in zoos, museums, and aquaria. Being a visitor is a strange experience, because I’ve been involved with these places for decades, working in museum collections and even helping to prepare exhibits on occasion. During family trips, I’ve come to realize how much my vocation can make me numb to the beauty and sublime complexity of our world and our bodies. I teach and write about millions of years of history and about bizarre ancient worlds, and usually my interest is detached and analytic. Now I’m experiencing science with my children—in the kinds of places where I discovered my love for it in the first place. One special moment happened recently with my son at the Museum of Science and Industry in Chicago. We’ve gone there regularly over the past three years because of his love of trains and the fact that there is a huge model railroad smack in the center of the place. I’ve spent countless hours at that one exhibit tracing model locomotives on their little trek from Chicago to Seattle. After a number of weekly visits 263 to this shrine for the train-obsessed, Nathaniel and I walked to corners of the museum we had failed to visit during our train-watching ventures or occasional forays to the full-size tractors and planes. In the back of the museum, in the Henry Crown Space Center, model planets hang from the ceiling and space suits lie in cases together with other memorabilia of the space program of the 1960s and 1970s. -

Scientists Speak 19.2 NEIL SHUBIN: When I Look at My Fellow Humans, I

Scientists Speak 19.2 NEIL SHUBIN: When I look at my fellow humans, I see ghosts of animals past. Glimpses of an epic story that is hidden inside us all. My name is Neil Shubin. As a scientist, I look at human bodies different from most people. The way we grip with our hands, we can thank our primate ancestors for that. How we hear so many sounds that dates back to creatures the size of a shrew. And the further back we go, the stranger it gets. To reveal why we look the way we do, we'll travel through the distant reaches of our family tree and meet an unusual cast of characters. The ancestors that shaped your body. The family you never knew you had. From the badlands of Ethiopia! “She's beautiful.” To the shores of Nova Scotia. “This is the spot.” We'll search for clues that lie buried in rock. “His eyes are like globes and he is like,” ‘I found it! I found it!’ And in search for answers written in our DNA. “I think it gives us a glimpse into the brain of our ancestors,” “I mean I find that mind-blowing.” The adventure begins with a search for some of our most elusive relatives. Fish that crawled onto land hundreds of millions of years ago. From our necks and lungs, to our limbs and hands, we owe a lot to these intrepid pioneers. So if you really want to see why you're built the way you are, it's time to meet your inner fish. -

New Fossil Species from a Fish-Eat-Fish World When Limbed Animals Evolved 27 March 2013

New fossil species from a fish-eat-fish world when limbed animals evolved 27 March 2013 Dr. Neil Shubin and Dr. Farish A. Jenkins, Jr., was first described in Nature in 2006.This species received scientific and popular acclaim for providing some of the clearest evidence of the evolutionary transition from lobe-finned fish to limbed animals, or tetrapods. Daeschler and his colleagues from the Tiktaalik research, including Academy research associate Dr. Jason Downs, have now described another new lobe-finned fish species from the same time and place in the Canadian Arctic. They describe the new species, Holoptychius bergmanni, in the latest This shows portions of the skull (left and center) and issue of the Proceedings of the Academy of Natural lower jaw (right) of Holoptychius bergmanni. Credit: Sciences of Philadelphia. Academy of Natural Sciences of Drexel University, with drawings by Scott Rawlins "We're fleshing out our knowledge of the community of vertebrates that lived at this important location," said Downs, who was lead author of the paper. He said describing species from this Scientists who famously discovered the lobe-finned important time and place will help the scientific fish fossil Tiktaalik roseae, a species with some of community understand the transition from finned the clearest evidence of the evolutionary transition vertebrates to limbed vertebrates that occurred in from fish to limbed animals, have described this ecosystem. another new species of predatory fossil lobe-finned fish fish from the same time and place. By "It was a tough world back there in the Devonian. describing more Devonian species, they're gaining There were a lot of big predatory fish with big teeth a greater understanding of the "fish-eat-fish world" and heavy armor of interlocking scales on their that drove the evolution of limbed vertebrates. -

Edward B. Daeschler (Ted)

Edward B. Daeschler (Ted) Address Vertebrate Zoology Academy of Natural Sciences 1900 Benjamin Franklin Parkway Philadelphia, PA 19103 USA [email protected] Education 1993 -1998 University of Pennsylvania, Ph.D., Department of Earth and Environmental Science 1982 -1985 University of California at Berkeley, M.S., Department of Paleontology 1977 -1981 Franklin and Marshall College, B.A., Department of Geology Professional Positions 2/2010 – 8/2010 Acting President and CEO, Academy of Natural Sciences of Philadelphia 9/2008 – present Vice President of the Center for Systematic Biology and Evolution and the Library, Academy of Natural Sciences of Philadelphia 6/2007 – present Associate Curator of Vertebrate Zoology, Academy of Natural Sciences of Philadelphia 1998 - 2007 Assistant Curator of Vertebrate Zoology, Academy of Natural Sciences of Philadelphia 1987 -1998 Collections Manager, Vertebrate Zoology, Academy of Natural Sciences of Philadelphia 1987 Research Assistant, Museum of Northern Arizona 1982 -1984 Senior Museum Preparator, University of California Museum of Paleontology Scientific Societies Society of Vertebrate Paleontology The Paleontological Society Geological Society of America Society for the Preservation of Natural History Collections International Working Group on Paleozoic Fishes/Microvertebrates Sigma Xi , Scientific Research Society Selected Publications Daeschler, E. B. and N. H. Shubin. 1998. Fish with Fingers?. Nature 391:133. Daeschler, E. B. 2000. An early actinopterygian fish from the Upper Devonian Catskill Formation in Pennsylvania, USA. Proceedings of the Academy of Natural Sciences 150:181-192. Daeschler, E. B. 2000. Early tetrapod jaws from the Late Devonian of Pennsylvania, USA. Journal of Paleontology 74(2):301-308. Daeschler, E. B., A. Frumes and C. F. Mullison. -

Shipman (2006)

A reprint from American Scientist the magazine of Sigma Xi, The Scientific Research Society This reprint is provided for personal and noncommercial use. For any other use, please send a request to Permissions, American Scientist, P.O. Box 13975, Research Triangle Park, NC, 27709, U.S.A., or by electronic mail to [email protected]. ©Sigma Xi, The Scientific Research Society and other rightsholders Marginalia Missing Links and Found Links Pat Shipman hough missing links are of- sion enhanced by its four-to-nine-foot Tten talked about, it’s the found In and out of the length. Its skeleton differs markedly ones that hold a special place in my from those of crocodiles or alligators, heart. Found links are fossils that il- though, despite the overall resemblance lustrate major transitions during evo- water, transitional in body shape. Tiktaalik’s front fins hold lutionary history. More than that, such the biggest surprise. Each was a sort of creatures offer unexpected glimpses of forms from the fossil half-fin, half-leg containing the bony the never-predictable twists and turns elements found in a limb—with a func- taken by evolution. Their discovery record illuminate tional wrist, elbow and shoulder—and and surprise bring sheer fun to pale- yet retaining the bony “rays” of a fish ontology and biology. the nuts and bolts of fin. According to team member Farish I have always loved the iconic Arch- Jenkins, Jr., of Harvard University, the aeopteryx, a beautiful fossil recognized evolution front fins were sturdy enough to sup- in 1860 that unmistakably combines port the creature in very shallow water features of two major groups of ani- or on land for brief trips. -

Twenty-First-Century Anatomy Lesson Polymath Pieces Together the Surprising Past of the Human Body from Fins, Wings, Hangovers and Hiccups

Vol 451|17 January 2008 BOOKS & ARTS Twenty-first-century anatomy lesson Polymath pieces together the surprising past of the human body from fins, wings, hangovers and hiccups. Your Inner Fish: A Journey into the fins, including some wrist bones. And while 3.5-Billion-Year History of the Human Body Shubin and his colleagues were digging up by Neil Shubin Tiktaalik in the Arctic, some of his students Allen Lane/Pantheon: 2008. 240pp. stayed behind in Chicago to find equally use- £20/$24 ful clues about the transition from sea to land in the genes that help build the fins of sharks Carl Zimmer and paddlefish. Six hundred years ago, anatomists were rock Your Inner Fish combines Shubin’s and oth- stars. Their lessons filled open-air amphithea- ers’ discoveries to present a twenty-first-century tres, where the curious public rubbed shoulders anatomy lesson. The simple, passionate writing with medical students. While a surgeon sliced may turn more than a few high-school students open a cadaver, the anatomist, seated above on into aspiring biologists. And it covers a lot of a lofty chair, deciphered the exposed mysteries ground. Shubin inspects our eyeballs, noses of the bones, muscles and organs. and hands to demonstrate how much we have Modern anatomists have retreated from in common with other animals. He notes how the stage to windowless medical-school labs. networks of genes for simple traits can expand They have ceded their public role to geneti- and diversify until they build new complex cists unveiling secrets encrypted in our DNA. -

Qnas with Neil Shubin

QNAS QNAS QnAs with Neil Shubin Prashant Nair “ ” Science Writer with a four wheel drive, such as animals that walk on land using limbs. PNAS: Your 2006 description of Tiktaalik furnished a view of the animal’sfrontend. From the rust-brown sediments of long-dried their saga of evolution in his PNAS Inau- Why did it take so long to disinter and de- streams that once rumbled through the rug- gural Article (1). scribe the pelvic appendage? ’ PNAS: Your discovery of Tiktaalik’spelvic ged terrain of Canada s Ellesmere Island, a Shubin: We had collected two blocks of appendage addresses a longstanding conun- team of paleontologists unearthed in 2004 specimens in 2004, one of which contained fi drum in the evolution of locomotion in the fossils of a 375 million-year-old species of sh the front end of the Tiktaalik reference spec- animal kingdom: the contrast between move- that may have nearly crossed an evolutionary imen described in the 2006 papers. We did Tiktaalik roseae ment using fins in the front of the body and Rubicon. Named ,thenow- not look at the second block right away, movement using appendages in the front and extinct animal has come to represent an in- mainly because it didn’tseemtocontain back. Can you explain the evolutionary sig- termediate link between fish and amphibians, much bone and because we had collected nificance of the distinction between these its features likely enabling a leap from water it for the sake of completeness. It took us forms of locomotion? to land. Led by National Academy of Sciences a number of years to prepare, study, and Shubin: Limbed vertebrates, or terapods, member Neil Shubin, a paleontologist at the draw conclusions about this pelvic structure, have four appendages, two in the front and University of Chicago, the team described the found in the second block, partly because the two in the back.