Tetrapod Evolution Resources on HHMI Biointeractive

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Nothing in Biology Makes Sense Except in the Light of Evolution: Pattern, Pro Cess, and the Evidence

Nothing in Biology Makes Sense Except in the Light of Evolution: Pattern, Pro cess, and the Evidence Jonathan B. Losos Evolutionary biology is unusual: unlike any other science, evolution- ary biologists study a phenomenon that some people do not think exists. Consider chemistry, for example; it is unlikely that anyone does not believe in the existence of chemical reactions. Ditto for the laws of physics. Even within biology, no one believes that cells do not exist nor that DNA is a fraud. But public opinion polls consistently show that a majority of the American public is either unsure about or does not believe that life has evolved through time. For example, a Gallup poll taken repeatedly over the past twenty years indicates that as much as 40 percent of the population believes that the Bible is liter- ally correct. When I teach evolutionary biology, I focus on the ideas about how evolution works, rather than on the empirical record of how species have changed through time. However, for one lecture period I make an exception, and in some respects I consider this the most important lecture of the semester. Sad as I fi nd it to be, most of my students will not go on to become evolutionary biologists. Rather, they will become leaders in many diverse aspects of society: doctors, lawyers, business- people, clergy, and artists; people to whom others will look for guid- ance on matters of knowledge and science. For this reason, although I devote my course to a detailed understanding of the evolutionary pro cess, I consider it vitally important that my students understand why it is that almost all biologists fi nd the evidence that evolution has occurred— and continues to occur— to be overwhelming. -

The Fish That Crawled out of the Water

Published online 5 April 2006 | Nature | doi:10.1038/news060403-7 News The fish that crawled out of the water A newly found fossil links fish to land-lubbers. Rex Dalton A crucial fossil that shows how animals crawled out from the water, evolving from fish into land-loving animals, has been found in Canada. The creature, described today in Nature1,2, lived some 375 million years ago. Palaeontologists are calling the specimen from the Devonian a true 'missing link', as it helps to fill in a gap in our understanding of how fish developed legs for land mobility, before eventually evolving into modern animals including mankind. Several samples of the fish-like tetrapod, named Tiktaalik roseae, were “Tetrapods did not so much discovered by Edward Daeschler of the Academy of Natural Sciences in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, Neil Shubin of the University of Chicago in conquer the land, The fossilized remains of as escape from the Illinois, Farish Jenkins of Harvard University in Cambridge, Massachusetts Tiktaalik show a crocodile-like water.” and colleagues. creature with joints in its front arms. The crew found the samples in a river delta on Ellesmere Island in Arctic credit Ted Daeschler Canada; these included a near-complete front half of a fossilized skeleton of a crocodile-like creature, whose skull is some 20 centimetres long. The beast has bony scales and fins, but the front fins are on their way to becoming limbs; they have the internal skeletal structure of an arm, including elbows and wrists, but with fins instead of clear fingers. The team is still looking for more complete specimens to get a better picture of hind part of the animal. -

High School Living Earth Evidence for Evolution Lessons Name: School: Teacher

DO NOT EDIT--Changes must be made through “File info” CorrectionKey=CA-B High School Living Earth Evidence for Evolution Lessons Name: School: Teacher: The Unit should take approximately 4 days complete. Read each section and complete the tasks. DO NOT EDIT--Changes must be made through “File info” CorrectionKey=CA-B FIGURE 1: This creosote ring in the Mojave Desert is estimated to be 11 700 years old . This makes it one of the oldest living organisms on Earth . The creosote bush is thought to be the most drought-tolerant plant in North America. It has a variety of adaptations to its desert environment, including its reproductive tendency to clone outward in rings rather than rely solely on seed production. The plant’s leaves are coated in a foul-tasting resin that protects it from water loss through evaporation and from grazing. It only opens its stomata in the morning to pull in carbon dioxide for photosynthesis from the more humid air and closes them as the day’s temperature increases. It also has a root system that consists of both an exceptionally long tap root and a vast network of shallow feeder roots. Creosote bushes exhibit two different shapes to fit different microclimates. In drier areas, the plant has a cone shape in which stems funnel rainwater into the taproot. In wetter areas, the bush has a more rounded shape that provides shade to its shallow feeder roots. PREDICT How do species change over time to adjust to varying conditions? DRIVING QUESTIONS As you move through the unit, gather evidence to help you answer the following questions. -

Farish A. Jenkins Jr (1940–2012) Palaeontologist, Anatomist, Explorer and Artist

COMMENT OBITUARY Farish A. Jenkins Jr (1940–2012) Palaeontologist, anatomist, explorer and artist. ith a rifle strapped to his back nearly a century’s worth of speculation about a serendipitous expansion of his research each summer, a scalpel in his functional anatomy that had been based on programme to include other tetrapod hand each autumn and the eyes fossils alone. groups. In the 1990s and 2000s, Jenkins used Wof an artist throughout the year, Farish Jenkins’s research output was as systematic the same approach to open up the Triassic Jenkins Jr seamlessly blended expeditionary as his military training had been. During the rocks of Greenland and the Devonian palaeontology with experimental sediments of Arctic Canada to anatomy to establish how animals palaeontological discovery. He evolved to walk, run, jump and fly. uncovered haramiyids (some of the Jenkins, who died of com- earliest mammals) in the Triassic plications from pneumonia on rocks and Tiktaalik (a genus of lobe- 11 November, was raised in Rye, finned fish) in the Devonian ones. New York. As a child, he showed Jenkins was president of the no obvious draw towards a life of Society of Vertebrate Paleontology science and exploration. But two in 1981–82, and he received its experiences transformed him. While Romer-Simpson Medal for life- S. KREITER/BOSTON GLOBE VIA GETTY VIA GETTY GLOBE S. KREITER/BOSTON studying philosophy at Princeton time achievement in 2009. He will University in New Jersey in the early be remembered by generations 1960s, Jenkins spent a summer as an of undergraduates, graduate and undergraduate assistant to Glenn medical students and assistant Lowell Jepsen. -

Transitional Fossils by Greg

Transitional Fossils By Greg Neyman © Answers In Creation Answers In Creation Website www.answersincreation.org/transitional_fossils.htm Transitional fossils, or the supposed lack thereof, has been used for many years by anti-evolutionists to argue against evolution. Here, I will explain what a transitional fossil is, and why it is not valid as an argument against evolution. A transitional fossil shows the evolutionary development from one species to another. For example, if organism 1 existed 70 million years ago, and organism 2 shows up in the fossil record 5 million years later, then theoretically there should be intermediate species in this 5 million year gap, which shows gradual progression from one species to another. The lack of these "transitional" fossils is proof to young earth creationists that evolution is false. Evolutionists have shown that indeed there are transitional fossils, and there are plenty of examples of them. For instance, see http://www.talkorigins.org/faqs/faq- transitional.html . Here is the key point...even if young earth creationists accept these examples of transitional fossils, they will still claim that there are no transitional fossils! These fossils will be called either unique species, or they will come up with some reason (disease, birth defect, etc) that accounts for the apparent transition feature. Naturally, they will say, "Where are the transitional fossils between these transitional fossils?" If we had a clear fossil record, showing progression every 10,000 years for millions of years, they will not believe it, and will want the "transitional" fossils for the missing 10,000 year period. No amount of evidence will convict them that their belief is wrong. -

Qnas with Neil Shubin

QNAS QNAS QnAs with Neil Shubin Prashant Nair “ ” Science Writer with a four wheel drive, such as animals that walk on land using limbs. PNAS: Your 2006 description of Tiktaalik furnished a view of the animal’sfrontend. From the rust-brown sediments of long-dried their saga of evolution in his PNAS Inau- Why did it take so long to disinter and de- streams that once rumbled through the rug- gural Article (1). scribe the pelvic appendage? ’ PNAS: Your discovery of Tiktaalik’spelvic ged terrain of Canada s Ellesmere Island, a Shubin: We had collected two blocks of appendage addresses a longstanding conun- team of paleontologists unearthed in 2004 specimens in 2004, one of which contained fi drum in the evolution of locomotion in the fossils of a 375 million-year-old species of sh the front end of the Tiktaalik reference spec- animal kingdom: the contrast between move- that may have nearly crossed an evolutionary imen described in the 2006 papers. We did Tiktaalik roseae ment using fins in the front of the body and Rubicon. Named ,thenow- not look at the second block right away, movement using appendages in the front and extinct animal has come to represent an in- mainly because it didn’tseemtocontain back. Can you explain the evolutionary sig- termediate link between fish and amphibians, much bone and because we had collected nificance of the distinction between these its features likely enabling a leap from water it for the sake of completeness. It took us forms of locomotion? to land. Led by National Academy of Sciences a number of years to prepare, study, and Shubin: Limbed vertebrates, or terapods, member Neil Shubin, a paleontologist at the draw conclusions about this pelvic structure, have four appendages, two in the front and University of Chicago, the team described the found in the second block, partly because the two in the back. -

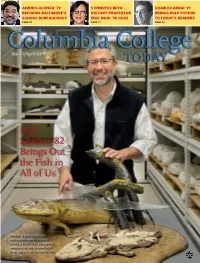

Neil Shubin '82 Brings out the Fish in All of Us

ANDRES ALONSO ’79 5 MINUTES WITH … CHARLES ARDAI ’91 REFORMS BALTIMORE’S HISTORY PROFESSOR BRINGS PULP FICTION SCHOOL BUREAUCRACY MAE NGAI ’98 GSAS TO TODAY’S READERS PAGE 22 PAGE 11 PAGE 24 Columbia College March/April 2011 TODAY Neil Shubin ’82 Brings Out the Fish in All of Us Shubin, a paleontologist and evolutionary biologist, co-led a team that discovered evidence of the pivotal shift from aquatic to terrestrial life. ust another J membership perk. Meet. Dine. Entertain. Join the Columbia Club and access state-of-the-art meeting rooms for your conferences and events. For more information or to apply, visit www.columbiaclub.org or call (212) 719-0380. The Columbia University Club of New York in residence at 15 West 43 St. New York, N Y 10036 Columbia’s SocialIntellectualCulturalRecreationalProfessional Resource in Midtown. Columbia College Today Contents 22 12 24 7 56 18 COVER STORY ALUMNI NEWS DEPARTMENTS G O FISH 27 O BITUARIES 2 LETTERS TO THE 12 Paleontologist and evolutionary biologist Neil Shubin 27 Joseph D. Coffee Jr. ’41 EDITOR ’82 brings out the fish in all of us. 28 Garland E. Wood ’65 3 ITHIN THE AMILY By Nathalie Alonso ’08 W F 30 B OOKSHEL F 4 AROUND THE QUADS FEATURES Featured: Adam Gidwitz ’04 4 turns classic folklore on its Northwest Corner Building Opens COLUMBIA FORUM ear with his new children’s 18 book, A Tale Dark & Grimm. 5 Rose, Jones Join In an excerpt from his book How Soccer Explains the College Senior Staff World: An Unlikely Theory of Globalization, Franklin 32 LASS OTES 6 Creed To Deliver Foer ’96 explains how one soccer club’s destiny was C N A LUMNI PRO F ILES Class Day Address shaped by European anti-Semitism. -

New Transitional Fossil from Late Jurassic of Chile Sheds Light on the Origin of Modern Crocodiles Fernando E

www.nature.com/scientificreports OPEN New transitional fossil from late Jurassic of Chile sheds light on the origin of modern crocodiles Fernando E. Novas1,2, Federico L. Agnolin1,2,3*, Gabriel L. Lio1, Sebastián Rozadilla1,2, Manuel Suárez4, Rita de la Cruz5, Ismar de Souza Carvalho6,8, David Rubilar‑Rogers7 & Marcelo P. Isasi1,2 We describe the basal mesoeucrocodylian Burkesuchus mallingrandensis nov. gen. et sp., from the Upper Jurassic (Tithonian) Toqui Formation of southern Chile. The new taxon constitutes one of the few records of non‑pelagic Jurassic crocodyliforms for the entire South American continent. Burkesuchus was found on the same levels that yielded titanosauriform and diplodocoid sauropods and the herbivore theropod Chilesaurus diegosuarezi, thus expanding the taxonomic composition of currently poorly known Jurassic reptilian faunas from Patagonia. Burkesuchus was a small‑sized crocodyliform (estimated length 70 cm), with a cranium that is dorsoventrally depressed and transversely wide posteriorly and distinguished by a posteroventrally fexed wing‑like squamosal. A well‑defned longitudinal groove runs along the lateral edge of the postorbital and squamosal, indicative of a anteroposteriorly extensive upper earlid. Phylogenetic analysis supports Burkesuchus as a basal member of Mesoeucrocodylia. This new discovery expands the meagre record of non‑pelagic representatives of this clade for the Jurassic Period, and together with Batrachomimus, from Upper Jurassic beds of Brazil, supports the idea that South America represented a cradle for the evolution of derived crocodyliforms during the Late Jurassic. In contrast to the Cretaceous Period and Cenozoic Era, crocodyliforms from the Jurassic Period are predomi- nantly known from marine forms (e.g., thalattosuchians)1. -

Your Inner Fish : a Journey Into the 3.5-Billion-Year History of the Human Body / by Neil Shubin.—1St Ed

EPILOGUE As a parent of two young children, I find myself spending a lot of time lately in zoos, museums, and aquaria. Being a visitor is a strange experience, because I’ve been involved with these places for decades, working in museum collections and even helping to prepare exhibits on occasion. During family trips, I’ve come to realize how much my vocation can make me numb to the beauty and sublime complexity of our world and our bodies. I teach and write about millions of years of history and about bizarre ancient worlds, and usually my interest is detached and analytic. Now I’m experiencing science with my children—in the kinds of places where I discovered my love for it in the first place. One special moment happened recently with my son at the Museum of Science and Industry in Chicago. We’ve gone there regularly over the past three years because of his love of trains and the fact that there is a huge model railroad smack in the center of the place. I’ve spent countless hours at that one exhibit tracing model locomotives on their little trek from Chicago to Seattle. After a number of weekly visits 263 to this shrine for the train-obsessed, Nathaniel and I walked to corners of the museum we had failed to visit during our train-watching ventures or occasional forays to the full-size tractors and planes. In the back of the museum, in the Henry Crown Space Center, model planets hang from the ceiling and space suits lie in cases together with other memorabilia of the space program of the 1960s and 1970s. -

Scientists Speak 19.2 NEIL SHUBIN: When I Look at My Fellow Humans, I

Scientists Speak 19.2 NEIL SHUBIN: When I look at my fellow humans, I see ghosts of animals past. Glimpses of an epic story that is hidden inside us all. My name is Neil Shubin. As a scientist, I look at human bodies different from most people. The way we grip with our hands, we can thank our primate ancestors for that. How we hear so many sounds that dates back to creatures the size of a shrew. And the further back we go, the stranger it gets. To reveal why we look the way we do, we'll travel through the distant reaches of our family tree and meet an unusual cast of characters. The ancestors that shaped your body. The family you never knew you had. From the badlands of Ethiopia! “She's beautiful.” To the shores of Nova Scotia. “This is the spot.” We'll search for clues that lie buried in rock. “His eyes are like globes and he is like,” ‘I found it! I found it!’ And in search for answers written in our DNA. “I think it gives us a glimpse into the brain of our ancestors,” “I mean I find that mind-blowing.” The adventure begins with a search for some of our most elusive relatives. Fish that crawled onto land hundreds of millions of years ago. From our necks and lungs, to our limbs and hands, we owe a lot to these intrepid pioneers. So if you really want to see why you're built the way you are, it's time to meet your inner fish. -

New Fossil Species from a Fish-Eat-Fish World When Limbed Animals Evolved 27 March 2013

New fossil species from a fish-eat-fish world when limbed animals evolved 27 March 2013 Dr. Neil Shubin and Dr. Farish A. Jenkins, Jr., was first described in Nature in 2006.This species received scientific and popular acclaim for providing some of the clearest evidence of the evolutionary transition from lobe-finned fish to limbed animals, or tetrapods. Daeschler and his colleagues from the Tiktaalik research, including Academy research associate Dr. Jason Downs, have now described another new lobe-finned fish species from the same time and place in the Canadian Arctic. They describe the new species, Holoptychius bergmanni, in the latest This shows portions of the skull (left and center) and issue of the Proceedings of the Academy of Natural lower jaw (right) of Holoptychius bergmanni. Credit: Sciences of Philadelphia. Academy of Natural Sciences of Drexel University, with drawings by Scott Rawlins "We're fleshing out our knowledge of the community of vertebrates that lived at this important location," said Downs, who was lead author of the paper. He said describing species from this Scientists who famously discovered the lobe-finned important time and place will help the scientific fish fossil Tiktaalik roseae, a species with some of community understand the transition from finned the clearest evidence of the evolutionary transition vertebrates to limbed vertebrates that occurred in from fish to limbed animals, have described this ecosystem. another new species of predatory fossil lobe-finned fish fish from the same time and place. By "It was a tough world back there in the Devonian. describing more Devonian species, they're gaining There were a lot of big predatory fish with big teeth a greater understanding of the "fish-eat-fish world" and heavy armor of interlocking scales on their that drove the evolution of limbed vertebrates. -

A Brief History of Whale Evolution: As Supported by The

A Brief History of Whale Evolution As Supported By the Fossil Record BIOB 272 – Genetics and Evolution Presented by Mindy Flanders Presented for Rick Henry December 8, 2017 Cetaceans—whales, dolphins, and porpoises—are so different from other animals that, until recently, scientists were unable to identify their closest relatives. As any elementary student knows, a whale is not a fish. That means that despite the similarities in where they live and how they look, whales are not at all like salmon or even sharks. Carolus Linnaeus, known for classifying plants and animals, noted in the 1750s that “whales breathe air through lungs not gills; are warm blooded; and have many other anatomical differences that distinguish them from fish” (Prothero, 2015). Other characteristics cetaceans share with all other mammals are: they have hair (at some point in their life), they give birth to live young, and they nurse their young with milk. This implies that whales evolved from other mammals and, because ancestral mammals were land animals, that whales had land ancestors (Thewissen & Bajpai, 2001). But before they had land ancestors they had water ancestors. The ancestors of fish lived in water, too. Up until 375 million years ago (mya), everything other than plants and insects lived in water, but it was around that time that fish and land animals began to diverge. A series of fossils represent the fish-to-tetrapod transition that occurred during the Late Devonian Period 359-383 mya (Herron & Freeman, 2014). In search of a new food source, or to escape predators more than twice their size (Prothero, 2015), the first tetrapods pushed themselves out of the swamps and began to live on land (Switek, 2010).