Civil-Military Integrations and PLA Reforms

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

INSTITUTE for POLICY REFORM Working Paper Series

339.5 • 1575 w-81 INSTITUTE • FOR POLICY REFORM • • • • WAITE MEMORIAL BOOK COLLECTION DEPT. OF AG. AND APPUED ECONOMICS 1994 BUFORD AVE. - 232 COB UNIVERSITY OF MINNESOTA ST. PAUL, MN 55108 U.S.A. • Working Paper Series The objective of the Institute enhance the foundation for broad based • for Policy Reform is to economic growth in developing countries. Through its research, education and training activities the Institute encourages active participation in the dialogue on policy reform, focusing on changes that stimulate and sustain economic development. At the core of these activities is the search for creative ideas that can be used to design constitutional, institutional and policy reforms. Research fellows and policy practitioners are engaged by IPR to expand • the analytical core of the reform process. This includes all elements of comprehensive and customized reforms packages, recognizing cultural, political, economic and environmental elements as crucial dimensions of societies. 1400 16th Street, NW / Suite 350 Washington, DC 20036 (202)3450 • 339.5 • 1575 w-81 INSTITUTE 0 FOR POLICY REFORM • IPR81 Federalism, Chinese Style: The Political Basis for Economic Success in China Barry Weingastl, Yingyi Qian2 and Gabriella Montinola3 * • WAITE MEMORIAL BOOK COLLECTION DEPT. OF AG. AND APPUED ECONOMICS 1994 BUFORD AVE. - 232 COB UNIVERSITY OF MINNESOTA ST. PAUL MN 56108 USA 0 Working Paper Series • The objective of the Institute for Policy Reform is to enhance the foundation for broad based economic growth in developing countries. Through its research, education and training activities the Institute encourages active participation in the dialogue on policy reform, focusing on changes that stimulate and sustain economic development. -

A Global Contest for Power and Influence

CHAPTER 1 U.S.-CHINA GLOBAL COMPETITION SECTION 1: A GLOBAL CONTEST FOR POWER AND INFLUENCE: CHINA’S VIEW OF STRA- TEGIC COMPETITION WITH THE UNITED STATES Key Findings • Beijing has long held the ambition to match the United States as the world’s most powerful and influential nation. Over the past 15 years, as its economic and technological prowess, dip- lomatic influence, and military capabilities have grown, China has turned its focus toward surpassing the United States. Chi- nese leaders have grown increasingly aggressive in their pur- suit of this goal following the 2008 global financial crisis and General Secretary of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) Xi Jinping’s ascent to power in 2012. • Chinese leaders regard the United States as China’s primary adversary and as the country most capable of preventing the CCP from achieving its goals. Over the nearly three decades of the post-Cold War era, Beijing has made concerted efforts to diminish the global strength and appeal of the United States. Chinese leaders have become increasingly active in seizing op- portunities to present the CCP’s one-party, authoritarian gover- nance system and values as an alternative model to U.S. global leadership. • China’s approach to competition with the United States is based on the CCP’s view of the United States as a dangerous ideologi- cal opponent that seeks to constrain its rise and undermine the legitimacy of its rule. In recent years, the CCP’s perception of the threat posed by Washington’s championing of liberal demo- cratic ideals has intensified as the Party has reemphasized the ideological basis for its rule. -

ACROSS the TAIWAN STRAIT: from COOPERATION to CONFRONTATION? 2013–2017

VOLUME 5 2014–2015 ACROSS THE TAIWAN STRAIT: from COOPERATION to CONFRONTATION? 2013–2017 Compendium of works from the China Leadership Monitor ALAN D. ROMBERG ACROSS THE TAIWAN STRAIT: from COOPERATION to CONFRONTATION? 2013–2017 Compendium of works from the China Leadership Monitor ALAN D. ROMBERG VOLUME FIVE July 28, 2014–July 14, 2015 JUNE 2018 Stimson cannot be held responsible for the content of any webpages belonging to other firms, organizations, or individuals that are referenced by hyperlinks. Such links are included in good faith to provide the user with additional information of potential interest. Stimson has no influence over their content, their correctness, their programming, or how frequently they are updated by their owners. Some hyperlinks might eventually become defunct. Copyright © 2018 Stimson All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means without prior written consent from Stimson. The Henry L. Stimson Center 1211 Connecticut Avenue Northwest, 8th floor Washington, DC 20036 Telephone: 202.223.5956 www.stimson.org Preface Brian Finlay and Ellen Laipson It is our privilege to present this collection of Alan Romberg’s analytical work on the cross-Strait relationship between the People’s Republic of China (PRC) and Taiwan. Alan joined Stimson in 2000 to lead the East Asia Program after a long and prestigious career in the Department of State, during which he was an instrumental player in the development of the United States’ policy in Asia, particularly relating to the PRC and Taiwan. He brought his expertise to bear on his work at Stimson, where he wrote the seminal book on U.S. -

The Construction and Characteristics of the Theoretical System of Xi Jinping’S View of History

Philosophy Study, August 2020, Vol. 10, No. 8, 503-510 doi: 10.17265/2159-5313/2020.08.004 D D AV I D PUBLISHING The Construction and Characteristics of the Theoretical System of Xi Jinping’s View of History YU Guirong Northeastern University, Shenyang, China Xi’s historical view is a scientific theoretical system with a tight logical structure. The construction of this theoretical system follows the principles and methods of the construction of Marxist theoretical system. The theoretical features of Xi’s view of history are unity of theory and practice, unity of politics and science, unity of universality and nationality, unity of collective wisdom and individual wisdom, unity of dialectical thinking and historical thinking, and unity of history, reality, and future. Keywords: Xi Jinping, view of history, construction, logical system Xi Jinping’s view of history is the significant inheritance and development of Marxist theory of history by the central leading collective of the Party with Comrade Xi Jinping at its core in the new era, and it is the Party’s fundamental viewpoint and view on history and its development as well as the basic principle and methodology for the Party to observe and study historical phenomena and problems. In the new era, to study Xi Jinping’s view of history, it is necessary to make an in-depth study and scientific exposition of the construction and characteristics of its theoretical system. The Construction of the Theoretical System of Xi’s View of History There is no doubt that the contents of Xi’s view of history are mainly put forward by Xi Jinping, with its theoretical content existing in its concrete theoretical form or text form as a natural form. -

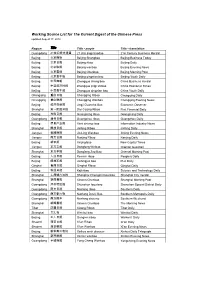

Working Source List for the Current Digest of the Chinese Press Updated August 17, 2012

Working Source List for The Current Digest of the Chinese Press updated August 17, 2012 Region Title Title - pinyin Title - translation Guangdong 21世纪经济报道 21 shiji jingji baodao 21st Century Business Herald Beijing 北京商报 Beijing Shangbao Beijing Business Today Beijing 北京日报 Beijing ribao Beijing Daily Beijing 北京晚报 Beijing wanbao Beijing Evening News Beijing 北京晨报 Beijing Chenbao Beijing Morning Post Beijing 北京青年报 Beijing qingnian bao Beijing Youth Daily Beijing 中国商報 Zhongguo shang bao China Business Herald Beijing 中国经济时报 Zhongguo jingji shibao China Economic Times Beijing 中国青年报 Zhongguo qingnian bao China Youth Daily Chongqing 重庆日报 Chongqing Ribao Chongqing Daily Chongqing 重庆晚报 Chongqing Wanbao Chongqing Evening News Beijing 经济观察报 Jingji Guancha Bao Economic Observer Shanghai 第一财经日报 Diyi Caijing Ribao First Financial Daily Beijing 光明日报 Guangming ribao Guangming Daily Guangdong 廣州日報 Guangzhou ribao Guangzhou Daily Beijing 信息产业报 Xinxi chanye bao Information Industry News Shanghai 解放日报 Jiefang Ribao Jiefang Daily Jiangsu 金陵晚报 Jin Ling Wanbao Jinling Evening News Jiangsu 南京日报 Nanjing Ribao Nanjing Daily Beijing 新京报 Xinjing bao New Capital Times Jiangsu 东方卫报 Dongfang Weibao Oriental Guardian Shanghai 东方早报 Dongfang Zao Bao Oriental Morning Post Beijing 人民日报 Renmin ribao People's Daily Beijing 解放军报 Jiefangjun bao PLA Daily Qinghai 青海日报 Qinghai Ribao Qinghai Daily Beijing 科技日报 Keji ribao Science and Technology Daily Shanghai 上海城市导报 Shanghai Chengshi Dao Bao Shanghai City Herald Shanghai 新闻晨报 Xinwen Chenbao Shanghai Morning Post Guangdong 深圳特区报 Shenzhen -

Education in China Since Mao

The Canadian Journal of Higher Education, Vol. X-l, 1980 Education in China Since Mao WILLIAM G. SAYWELL* ABSTRACT Policies in Chinese education, particularly higher education, have undergone major shifts since 1949 in response to general swings in Chinese policy, ideological debates and the political fortunes of different leaders and factions. These changes have involved shifts in emphasis between "redness"and "expertness", between education as a party device designed to inculcate and sustain revolutionary values and education as a governmental instrument used to promote modernization. In the most recent period since Mao's death and the "Gang of Four's" ouster in the fall of 1976, there has been a return to pragmatism with the radical policies and stress on political goals of the Cultural Revolution period giving way to a renewed emphasis on developing professional and technical skills. These objectives are being promoted by the reintroduction of earlier moderate policies governing curricula, admission standards and academic administration and by extraordinary measures, including international educational exchanges, designed to overcome the Cultural Revolution's disruptive impact. These new policies have provoked some criticism from those concerned about elitist aspects of the current system and a reduced commitment to socialist values. Since educational policy is highly sensitive to shifting political currents, future changes in this area will serve as a barometer of new political trends. RÉSUMÉ La politique de l'enseignement en Chine, particulièrement l'enseignement supérieur, a subi des changements majeurs depuis 1949 en réponse aux va-et-vient généraux de la politique chinoise, aux débats idéologiques et à la fortune politique des différents leaders et des dissensions. -

The Emergence of a Land Market in China

_o(*¿-5 THE EMERGENCE OF A I"AI\D IVIARKET IN CHINA A Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfilment of the Requirements For the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy by Jlang Bing to Department of Economics & Centre for Asia Studies The University of Adelaide Adelaide, Australia September 1994 v¡ø.JeJ \ 1Ú\5 ì Contents Contents of Chapters List of Tables List of Figures Abbreviations Research Declaration Acknowledgments Summar5r References CHAPTER I TNTRODUCTTON (P. 17) CFIAPTER 2 SOME THEORETICAL ISSUES IN THE ANALYSIS OF TFIE ECONOMICS OF CHINA'S IAND USE (p. 28) 2. r Ideological changes and the Reform of Land system (p. 2s) 2.2 Re-constructing china's Land ownership system (p. 83) 2.3 The Management of Land with and without a Land Market (P. 38) 2.4Land Prices and Land Uses (p. 42) 2 CFIAPTER 3 CHINA'S DUAL I.AND OWNER*SHIP SYSTEM AND I"AND ADMIMSTRATION (P. 50) 3.1 The Formation of Collective Ownership of Rural Land (P. 5r) 3.2 The Formation of State Ownership of Urban t and (P. 62) 3.3 The Relationship Between State Ownership of Urban Land and Collective Ownership of Rural Land (P. 66) 3.4 Issues Related to Land Ownership (P. 73) 3.5 Land Administration (P. 80) CFIAPTER 4 THE SUPPLY OF AND DEMAND FOR I.AND UNDER THE PI.ANNED ECONOIVTY SYSTEM (P. 93) 4.I The Supply of Land (P. 94) 4.2T}ae Demand for Land and Its Management (P. f 05) 4.3 The Planning and the Market: Problems with Land Supply in a Transitional Economy (P. -

Section 2: the China Model: Return of the Middle Kingdom

SECTION 2: THE CHINA MODEL: RETURN OF THE MIDDLE KINGDOM Key Findings • The Chinese Communist Party (CCP) seeks to revise the inter- national order to be more amenable to its own interests and authoritarian governance system. It desires for other countries not only to acquiesce to its prerogatives but also to acknowledge what it perceives as China’s rightful place at the top of a new hierarchical world order. • The CCP’s ambitions for global preeminence have been con- sistent throughout its existence: every CCP leader since Mao Zedong has proclaimed the Party would ultimately prove the superiority of its Marxist-Leninist system over the rest of the world. Under General Secretary of the CCP Xi Jinping, the Chi- nese government has become more aggressive in pursuing its interests and promoting its model internationally. • The CCP aims to establish an international system in which Beijing can freely influence the behavior and access the mar- kets of other countries while constraining the ability of others to influence its behavior or access markets it controls. The “com- munity of common human destiny,” the CCP’s proposed alter- native global governance system, is explicitly based on histor- ical Chinese traditions and presumes Beijing and the illiberal norms and institutions it favors should be the primary forces guiding globalization. • The CCP has attempted to use the novel coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic to promote itself as a responsible and benevolent global leader and to prove that its model of governance is su- perior to liberal democracy. Thus far, it appears Beijing has not changed many minds, if any. -

Chinese Alphabetization Reform: Intellectuals and Their Public Discourse, 1949-1958 Wansu Luo Iowa State University

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Digital Repository @ Iowa State University Iowa State University Capstones, Theses and Graduate Theses and Dissertations Dissertations 2018 Chinese alphabetization reform: Intellectuals and their public discourse, 1949-1958 Wansu Luo Iowa State University Follow this and additional works at: https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/etd Part of the History Commons Recommended Citation Luo, Wansu, "Chinese alphabetization reform: Intellectuals and their public discourse, 1949-1958" (2018). Graduate Theses and Dissertations. 16844. https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/etd/16844 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Iowa State University Capstones, Theses and Dissertations at Iowa State University Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Graduate Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Iowa State University Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Chinese alphabetization reform: Intellectuals and their public discourse, 1949-1958 by Wansu Luo A thesis submitted to the graduate faculty in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS Major: History Program of Study Committee: Tao Wang, Major Professor James T. Andrews Jonathan Hassid The student author, whose presentation of the scholarship herein was approved by the program of study committee, is solely responsible for the content of this thesis. The Graduate College will ensure this thesis is globally accessible and will not permit alterations after a degree is conferred. Iowa State University Ames, Iowa 2018 Copyright ©Wansu Luo, 2018. All rights reserved. ii TABLE OF CONTENTS Page ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS ........................................................................................................ -

China's Advancing Aerospace Industry

CHILDREN AND FAMILIES The RAND Corporation is a nonprofit institution that EDUCATION AND THE ARTS helps improve policy and decisionmaking through ENERGY AND ENVIRONMENT research and analysis. HEALTH AND HEALTH CARE This electronic document was made available from INFRASTRUCTURE AND www.rand.org as a public service of the RAND TRANSPORTATION Corporation. INTERNATIONAL AFFAIRS LAW AND BUSINESS NATIONAL SECURITY Skip all front matter: Jump to Page 16 POPULATION AND AGING PUBLIC SAFETY SCIENCE AND TECHNOLOGY Support RAND Purchase this document TERRORISM AND HOMELAND SECURITY Browse Reports & Bookstore Make a charitable contribution For More Information Visit RAND at www.rand.org Explore the RAND National Security Research Division View document details Limited Electronic Distribution Rights This document and trademark(s) contained herein are protected by law as indicated in a notice appearing later in this work. This electronic representation of RAND intellectual property is provided for non-commercial use only. Unauthorized posting of RAND electronic documents to a non-RAND website is prohibited. RAND electronic documents are protected under copyright law. Permission is required from RAND to reproduce, or reuse in another form, any of our research documents for commercial use. For information on reprint and linking permissions, please see RAND Permissions. This product is part of the RAND Corporation monograph series. RAND monographs present major research findings that address the challenges facing the public and private sectors. All RAND -

Chapter One: Introduction

Desire and Fantasy On-line: a Sociological and Psychoanalytical Approach to the Prosumption of Chinese Internet Fiction A Thesis Submitted to the University of Manchester for the Degree of PhD in the Faculty of Humanities 2012 SHIH-CHEN CHAO SCHOOL OF ARTS, LANGUAGES, AND CULTURES Table of Contents Abstract ......................................................................................................................... 7 Declaration ................................................................................................................... 8 Copyright Statement ................................................................................................... 8 Acknowledgement ........................................................................................................ 9 Chapter One: Introduction ....................................................................................... 10 1.1: Internet Literature – Definition and Development………………………...10 1.2: Research Motivation and Questions……………………………………...…18 1.3: Literature Review…………………………………………………………..19 1.3.1: Modern Chinese Literature and Popular Fiction……...………………19 1.3.2: Fan Culture in the Popular Media………...……………………….. 20 1.3.3: Literature and the Internet…………...……………………………….21 1.3.4: Popular Fiction and Internet in China………………...………………23 1.4: Theoretical Frameworks…………………………………….……………..28 1.5: Data and Methodology……………………………………………………. 30 1.5.1: The Primary Sources of Literary Commodities – Four Nets and One Channel on Qidian….……………………………………………….. 30 -

Research and Realization of Chinese Text Semantic Correction Based On

3rd International Conference on Education, Management, Arts, Economics and Social Science (ICEMAESS 2015) Research and realization of Chinese text semantic correction Based on Rule 1,a 1,b 1,c 1,d Yefan Wu , Runbo Zhuang , Ying Jiang and Fan Li 1School of Management, Beijing Normal University Zhuhai campus, Zhuhai 519000, China. [email protected], [email protected], [email protected], [email protected] Keywords: Chinese, semantic, correction, rules, collocation Abstract. Automatic correction is an important research field in natural language processing, it is still relatively weak in the text automatic correction technology on semantic level. This paper presents develop XML rules based on LanguageTool Chinese grammar correction, match error correction in semantic level for the content of the rule to write the corresponding rule base, and realize automatic detect the corresponding content of semantic error in the text, and put forward the corresponding modification suggestions and opinions. The experiments show a high correct rate that the process of correction the corpus, which shows that the research and implementation of semantic of Chinese text is very practical significance and valuable. The introduction Background and significance of research. Text is an important carrier of human social information. With the rapid development of whole society information process, the importance and urgency of text information correction is more and more obvious. The former researchers in the text of the technology has made great achievements, but their check wrong technology just based on the word level, dealing with more words, less word or wrong character correction in the text. If testing an essay about the text of population statistics in China, the correct expression is “我国人口统计(不 包括台湾、香港、澳门)”(“the population statistics of our country (excluding Taiwan, Hongkong, Macao”) but appear the “大陆人口统计”(“the population statistics of mainland”) in the text.