The Confucian Principles Behind the Chinese Communist Party's Mass

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Reception and Translation of Classical Chinese Poetry in English

NCUE Journal of Humanities Vol. 6, pp. 47-64 September, 2012 The Reception and Translation of Classical Chinese Poetry in English Chia-hui Liao∗ Abstract Translation and reception are inseparable. Translation helps disseminate foreign literature in the target system. An evident example is Ezra Pound’s translation based on the 8th-century Chinese poet Li Bo’s “The River-Merchant’s Wife,” which has been anthologised in Anglophone literature. Through a diachronic survey of the translation of classical Chinese poetry in English, the current paper places emphasis on the interaction between the translation and the target socio-cultural context. It attempts to stress that translation occurs in a context—a translated work is not autonomous and isolated from the literary, cultural, social, and political activities of the receiving end. Keywords: poetry translation, context, reception, target system, publishing phenomenon ∗ Adjunct Lecturer, Department of English, National Changhua University of Education. Received December 30, 2011; accepted March 21, 2012; last revised May 13, 2012. 47 國立彰化師範大學文學院學報 第六期,頁 47-64 二○一二年九月 中詩英譯與接受現象 廖佳慧∗ 摘要 研究翻譯作品,必得研究其在譯入環境中的接受反應。透過翻譯,外國文學在 目的系統中廣宣流布。龐德的〈河商之妻〉(譯寫自李白的〈長干行〉)即一代表實 例,至今仍被納入英美文學選集中。藉由中詩英譯的歷時調查,本文側重譯作與譯 入文境間的互動,審視前者與後者的社會文化間的關係。本文強調翻譯行為的發生 與接受一方的時代背景相互作用。譯作不會憑空出現,亦不會在目的環境中形成封 閉的狀態,而是與文學、文化、社會與政治等活動彼此交流、影響。 關鍵字:詩詞翻譯、文境、接受反應、目的/譯入系統、出版現象 ∗ 國立彰化師範大學英語系兼任講師。 到稿日期:2011 年 12 月 30 日;確定刊登日期:2012 年 3 月 21 日;最後修訂日期:2012 年 5 月 13 日。 48 The Reception and Translation of Classical Chinese Poetry in English Writing does not happen in a vacuum, it happens in a context and the process of translating texts form one cultural system into another is not a neutral, innocent, transparent activity. -

Uyghur Dispossession, Culture Work and Terror Capitalism in a Chinese Global City Darren T. Byler a Dissertati

Spirit Breaking: Uyghur Dispossession, Culture Work and Terror Capitalism in a Chinese Global City Darren T. Byler A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of Washington 2018 Reading Committee: Sasha Su-Ling Welland, Chair Ann Anagnost Stevan Harrell Danny Hoffman Program Authorized to Offer Degree: Anthropology ©Copyright 2018 Darren T. Byler University of Washington Abstract Spirit Breaking: Uyghur Dispossession, Culture Work and Terror Capitalism in a Chinese Global City Darren T. Byler Chair of the Supervisory Committee: Sasha Su-Ling Welland, Department of Gender, Women, and Sexuality Studies This study argues that Uyghurs, a Turkic-Muslim group in contemporary Northwest China, and the city of Ürümchi have become the object of what the study names “terror capitalism.” This argument is supported by evidence of both the way state-directed economic investment and security infrastructures (pass-book systems, webs of technological surveillance, urban cleansing processes and mass internment camps) have shaped self-representation among Uyghur migrants and Han settlers in the city. It analyzes these human engineering and urban planning projects and the way their effects are contested in new media, film, television, photography and literature. It finds that this form of capitalist production utilizes the discourse of terror to justify state investment in a wide array of policing and social engineering systems that employs millions of state security workers. The project also presents a theoretical model for understanding how Uyghurs use cultural production to both build and refuse the development of this new economic formation and accompanying forms of gendered, ethno-racial violence. -

Han Fei and the Han Feizi

Introduction: Han Fei and the Han Feizi Paul R. Goldin Han Fei 韓非 was the name of a proli fi c Chinese philosopher who (according to the scanty records available to us) was executed on trumped up charges in 233 B.C.E. Han Feizi 韓非子, meaning Master Han Fei , is the name of the book purported to contain his writings. In this volume, we distinguish rigorously between Han Fei (the man) and Han Feizi (the book) for two main reasons. First, the authenticity of the Han Feizi —or at least of parts of it—has long been doubted (the best studies remain Lundahl 1992 and Zheng Liangshu 1993 ) . This issue will be revisited below; for now, suffi ce to it to say that although the contributors to this volume accept the bulk of it as genuine, one cannot simply assume that Han Fei was the author of everything in the Han Feizi . Indeed, there is a memorial explic- itly attributed to Han Fei’s rival Li Si 李斯 (ca. 280–208 B.C.E.) in the pages of the Han Feizi ( Chen Qiyou 陳奇猷 2000 : 1.2.42–47); some scholars fear that other material in the text might also be the work of people other than Han Fei. Second, and no less importantly, even if Han Fei is responsible for the lion’s share of the extant Han Feizi , a reader must be careful not to identify the philosophy of Han Fei himself with the philosophy (or philosophies) advanced in the Han Feizi , as though these were necessarily the same thing. -

Han Feizi's Criticism of Confucianism and Its Implications for Virtue Ethics

JOURNAL OF MORAL PHILOSOPHY Journal of Moral Philosophy 5 (2008) 423–453 www.brill.nl/jmp Han Feizi’s Criticism of Confucianism and its Implications for Virtue Ethics * Eric L. Hutton Department of Philosophy, University of Utah, 215 S. Central Campus Drive, CTIHB, 4th fl oor, Salt Lake City, UT 84112, USA [email protected] Abstract Several scholars have recently proposed that Confucianism should be regarded as a form of virtue ethics. Th is view off ers new approaches to understanding not only Confucian thinkers, but also their critics within the Chinese tradition. For if Confucianism is a form of virtue ethics, we can then ask to what extent Chinese criticisms of it parallel criticisms launched against contemporary virtue ethics, and what lessons for virtue ethics in general might be gleaned from the challenges to Confucianism in particular. Th is paper undertakes such an exercise in examining Han Feizi, an early critic of Confucianism. Th e essay off ers a careful interpretation of the debate between Han Feizi and the Confucians and suggests that thinking through Han Feizi’s criticisms and the possible Confucian responses to them has a broader philosophical payoff , namely by highlighting a problem for current defenders of virtue ethics that has not been widely noticed, but deserves attention. Keywords Bernard Williams, Chinese philosophy, Confucianism, Han Feizi, Rosalind Hursthouse, virtue ethics Although Confucianism is now almost synonymous with Chinese culture, over the course of history it has also attracted many critics from among the Chinese themselves. Of these critics, one of the most interesting is Han Feizi (ca. -

INSTITUTE for POLICY REFORM Working Paper Series

339.5 • 1575 w-81 INSTITUTE • FOR POLICY REFORM • • • • WAITE MEMORIAL BOOK COLLECTION DEPT. OF AG. AND APPUED ECONOMICS 1994 BUFORD AVE. - 232 COB UNIVERSITY OF MINNESOTA ST. PAUL, MN 55108 U.S.A. • Working Paper Series The objective of the Institute enhance the foundation for broad based • for Policy Reform is to economic growth in developing countries. Through its research, education and training activities the Institute encourages active participation in the dialogue on policy reform, focusing on changes that stimulate and sustain economic development. At the core of these activities is the search for creative ideas that can be used to design constitutional, institutional and policy reforms. Research fellows and policy practitioners are engaged by IPR to expand • the analytical core of the reform process. This includes all elements of comprehensive and customized reforms packages, recognizing cultural, political, economic and environmental elements as crucial dimensions of societies. 1400 16th Street, NW / Suite 350 Washington, DC 20036 (202)3450 • 339.5 • 1575 w-81 INSTITUTE 0 FOR POLICY REFORM • IPR81 Federalism, Chinese Style: The Political Basis for Economic Success in China Barry Weingastl, Yingyi Qian2 and Gabriella Montinola3 * • WAITE MEMORIAL BOOK COLLECTION DEPT. OF AG. AND APPUED ECONOMICS 1994 BUFORD AVE. - 232 COB UNIVERSITY OF MINNESOTA ST. PAUL MN 56108 USA 0 Working Paper Series • The objective of the Institute for Policy Reform is to enhance the foundation for broad based economic growth in developing countries. Through its research, education and training activities the Institute encourages active participation in the dialogue on policy reform, focusing on changes that stimulate and sustain economic development. -

Comprehensive Encirclement

COMPREHENSIVE ENCIRCLEMENT: THE CHINESE COMMUNIST PARTY’S STRATEGY IN XINJIANG GARTH FALLON A thesis submitted for the degree of Master of Philosophy School of Humanities and Social Sciences International and Political Studies July 2018 1 THE UNIVERSITY OF NEW SOUTH WALES Thesis/Dissertation Sheet Surname or Family name: FALLON First name: Garth Other name/s: Nil Abbreviation for degree as given in the University calendar: MPhil School: Humanitiesand Social Sciences Faculty: UNSW Canberraat ADFA Title: Comprehensive encirclement: the Chinese Communist Party's strategy in Xinjiang Abstract 350 words maximum: (PLEASETYPE) This thesis argues that the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) has a strategy for securing Xinjiang - its far-flung predominantly Muslim most north-western province - through a planned program of Sinicisation. Securing Xinjiang would turna weakly defended 'back door' to China into a strategic strongpointfrom which Beijing canproject influence into Central Asia. The CCP's strategy is to comprehensively encircle Xinjiang with Han people and institutions, a Han dominated economy, and supporting infrastructure emanatingfrom inner China A successful program of Sinicisation would transform Xinjiang from a Turkic-language-speaking, largely Muslim, physically remote, economically under-developed region- one that is vulnerable to separation from the PRC - into one that will be substantially more culturally similar to, and physically connected with, the traditional Han-dominated heartland of inner China. Once achieved, complete Sinicisation would mean Xinjiang would be extremely difficult to separate from China. In Xinjiang, the CCP enacts policies in support of Sinication across all areas of statecraft. This thesis categorises these activities across three dimensions: the economic and demographic dimension, the political and cultural dimension, and the security and international cooperationdimension. -

A Comparison Between Ancient Greek and Chinese Philosophy on Politics Qihan Long1, A

Advances in Social Science, Education and Humanities Research, volume 215 3rd International Conference on Modern Management, Education Technology, and Social Science (MMETSS 2018) A Comparison between Ancient Greek and Chinese Philosophy on Politics Qihan Long1, a 1 BA History, Royal Holloway University of London, Surrey, TW20 0EX, England aemail Keywords: Ancient Greek philosophy, Chinese philosophy, Politics Abstract. Although being two opposite ends of the Eurasian continent, the Greek and Chinese philosophers in the period of 600 BC to 300 BC came with some similar cures for the government. Both Greek and Chinese philosophers emphasized the importance of harmony, virtue and music in politics. Furthermore, in regard to the differences between ancient Greek and ancient Chinese philosophies on politics, it is interesting to note that Aristotle described democracy as the most tolerable one of three perverted form of government. Despite the fact that ancient China never truly formed an aristocracy nor a constitutional political entity, the ideas of Western and Eastern philosophers resonated with each other and formed the brightest light in the human history. 1. Introduction From 600 BC to 300 BC, it was a golden age for philosophy. Ideas and thoughts were formed in different areas in the world. During this period, great philosophers appeared from Greece in the west to China in the east. In the west, the most prominent philosophers were Socrates, Plato and Aristotle, while in the east, the great philosophers, such as Lao Zi, Confucius and Han Fei accomplished their works in China. Most of the philosophers in that period addressed the ideal form of government and how to rule a state. -

A Global Contest for Power and Influence

CHAPTER 1 U.S.-CHINA GLOBAL COMPETITION SECTION 1: A GLOBAL CONTEST FOR POWER AND INFLUENCE: CHINA’S VIEW OF STRA- TEGIC COMPETITION WITH THE UNITED STATES Key Findings • Beijing has long held the ambition to match the United States as the world’s most powerful and influential nation. Over the past 15 years, as its economic and technological prowess, dip- lomatic influence, and military capabilities have grown, China has turned its focus toward surpassing the United States. Chi- nese leaders have grown increasingly aggressive in their pur- suit of this goal following the 2008 global financial crisis and General Secretary of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) Xi Jinping’s ascent to power in 2012. • Chinese leaders regard the United States as China’s primary adversary and as the country most capable of preventing the CCP from achieving its goals. Over the nearly three decades of the post-Cold War era, Beijing has made concerted efforts to diminish the global strength and appeal of the United States. Chinese leaders have become increasingly active in seizing op- portunities to present the CCP’s one-party, authoritarian gover- nance system and values as an alternative model to U.S. global leadership. • China’s approach to competition with the United States is based on the CCP’s view of the United States as a dangerous ideologi- cal opponent that seeks to constrain its rise and undermine the legitimacy of its rule. In recent years, the CCP’s perception of the threat posed by Washington’s championing of liberal demo- cratic ideals has intensified as the Party has reemphasized the ideological basis for its rule. -

ACROSS the TAIWAN STRAIT: from COOPERATION to CONFRONTATION? 2013–2017

VOLUME 5 2014–2015 ACROSS THE TAIWAN STRAIT: from COOPERATION to CONFRONTATION? 2013–2017 Compendium of works from the China Leadership Monitor ALAN D. ROMBERG ACROSS THE TAIWAN STRAIT: from COOPERATION to CONFRONTATION? 2013–2017 Compendium of works from the China Leadership Monitor ALAN D. ROMBERG VOLUME FIVE July 28, 2014–July 14, 2015 JUNE 2018 Stimson cannot be held responsible for the content of any webpages belonging to other firms, organizations, or individuals that are referenced by hyperlinks. Such links are included in good faith to provide the user with additional information of potential interest. Stimson has no influence over their content, their correctness, their programming, or how frequently they are updated by their owners. Some hyperlinks might eventually become defunct. Copyright © 2018 Stimson All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means without prior written consent from Stimson. The Henry L. Stimson Center 1211 Connecticut Avenue Northwest, 8th floor Washington, DC 20036 Telephone: 202.223.5956 www.stimson.org Preface Brian Finlay and Ellen Laipson It is our privilege to present this collection of Alan Romberg’s analytical work on the cross-Strait relationship between the People’s Republic of China (PRC) and Taiwan. Alan joined Stimson in 2000 to lead the East Asia Program after a long and prestigious career in the Department of State, during which he was an instrumental player in the development of the United States’ policy in Asia, particularly relating to the PRC and Taiwan. He brought his expertise to bear on his work at Stimson, where he wrote the seminal book on U.S. -

The Construction and Characteristics of the Theoretical System of Xi Jinping’S View of History

Philosophy Study, August 2020, Vol. 10, No. 8, 503-510 doi: 10.17265/2159-5313/2020.08.004 D D AV I D PUBLISHING The Construction and Characteristics of the Theoretical System of Xi Jinping’s View of History YU Guirong Northeastern University, Shenyang, China Xi’s historical view is a scientific theoretical system with a tight logical structure. The construction of this theoretical system follows the principles and methods of the construction of Marxist theoretical system. The theoretical features of Xi’s view of history are unity of theory and practice, unity of politics and science, unity of universality and nationality, unity of collective wisdom and individual wisdom, unity of dialectical thinking and historical thinking, and unity of history, reality, and future. Keywords: Xi Jinping, view of history, construction, logical system Xi Jinping’s view of history is the significant inheritance and development of Marxist theory of history by the central leading collective of the Party with Comrade Xi Jinping at its core in the new era, and it is the Party’s fundamental viewpoint and view on history and its development as well as the basic principle and methodology for the Party to observe and study historical phenomena and problems. In the new era, to study Xi Jinping’s view of history, it is necessary to make an in-depth study and scientific exposition of the construction and characteristics of its theoretical system. The Construction of the Theoretical System of Xi’s View of History There is no doubt that the contents of Xi’s view of history are mainly put forward by Xi Jinping, with its theoretical content existing in its concrete theoretical form or text form as a natural form. -

China´S Cultural Fundamentals Behind Current Foreign Policy Journal Views: Heritage of Old Thinking Habits in Chinese Modern Thoughts

Lajčiak, M. (2017). China´s cultural fundamentals behind current foreign policy Journal views: Heritage of old thinking habits in Chinese modern thoughts. Journal of of International International Studies, 10(2), 9-27. doi:10.14254/2071-8330.2017/10-2/1 Studies © Foundation China´s cultural fundamentals behind of International current foreign policy views: Heritage of Studies, 2017 © CSR, 2017 old thinking habits in Chinese modern Scientific Papers thoughts Milan Lajčiak Ambassador of the Slovak Republic to the Republic of Korea Slovak Embassy in Seoul, South Korea Email: [email protected] Abstract. Different philosophical frameworks between China and the West found Received: December, 2016 their reflection in diverging concepts of managing relations with the outside 1st Revision: world. China focused more on circumstances, managing situation and preventing February, 2017 conflicts, the West was resolution oriented, aimed at fighting opponents and Accepted: March, 2017 looking for victory in conflicts. China has introduced the idea of harmony - hierarchy world, while the West, on the opposite, tends to freedom-conflict DOI: patterns of relations. On China’s side, thinking habits and old thought paradigms 10.14254/2071- of statecraft are until now deeply ingrained in mentality, thus shaping China´s 8330.2017/10-2/1 policy today. Understanding the background of Chinese traditional thinking modes and mind heritage helps better understanding of China´s rise in global affairs as well as of Sino-American relations as the key element in a search for global leadership. Keywords: China, West, thinking habits, foreign policy concepts, China rise, Sino- American relations. JEL Classification: F5, P5, Z1 1. -

History of China: Table of Contents

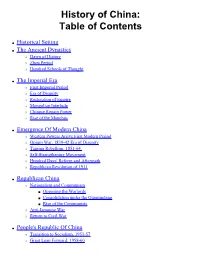

History of China: Table of Contents ● Historical Setting ● The Ancient Dynasties ❍ Dawn of History ❍ Zhou Period ❍ Hundred Schools of Thought ● The Imperial Era ❍ First Imperial Period ❍ Era of Disunity ❍ Restoration of Empire ❍ Mongolian Interlude ❍ Chinese Regain Power ❍ Rise of the Manchus ● Emergence Of Modern China ❍ Western Powers Arrive First Modern Period ❍ Opium War, 1839-42 Era of Disunity ❍ Taiping Rebellion, 1851-64 ❍ Self-Strengthening Movement ❍ Hundred Days' Reform and Aftermath ❍ Republican Revolution of 1911 ● Republican China ❍ Nationalism and Communism ■ Opposing the Warlords ■ Consolidation under the Guomindang ■ Rise of the Communists ❍ Anti-Japanese War ❍ Return to Civil War ● People's Republic Of China ❍ Transition to Socialism, 1953-57 ❍ Great Leap Forward, 1958-60 ❍ Readjustment and Recovery, 1961-65 ❍ Cultural Revolution Decade, 1966-76 ■ Militant Phase, 1966-68 ■ Ninth National Party Congress to the Demise of Lin Biao, 1969-71 ■ End of the Era of Mao Zedong, 1972-76 ❍ Post-Mao Period, 1976-78 ❍ China and the Four Modernizations, 1979-82 ❍ Reforms, 1980-88 ● References for History of China [ History of China ] [ Timeline ] Historical Setting The History Of China, as documented in ancient writings, dates back some 3,300 years. Modern archaeological studies provide evidence of still more ancient origins in a culture that flourished between 2500 and 2000 B.C. in what is now central China and the lower Huang He ( orYellow River) Valley of north China. Centuries of migration, amalgamation, and development brought about a distinctive system of writing, philosophy, art, and political organization that came to be recognizable as Chinese civilization. What makes the civilization unique in world history is its continuity through over 4,000 years to the present century.