Good Cop, Bad Cop Georgia's One Hundred Days of a New Democratic

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Georgia's October 2013 Presidential Election: Outcome and Implications

Georgia’s October 2013 Presidential Election: Outcome and Implications Jim Nichol Specialist in Russian and Eurasian Affairs November 4, 2013 Congressional Research Service 7-5700 www.crs.gov R43299 Georgia’s October 2013 Presidential Election: Outcome and Implications Summary This report discusses Georgia’s October 27, 2013, presidential election and its implications for U.S. interests. The election took place one year after a legislative election that witnessed the mostly peaceful shift of legislative and ministerial power from the ruling party, the United National Movement (UNM), to the Georgia Dream (GD) coalition bloc. The newly elected president, Giorgi Margvelashvili of the GD, will have fewer powers under recently approved constitutional changes. Most observers have viewed the 2013 presidential election as marking Georgia’s further progress in democratization, including a peaceful shift of presidential power from UNM head Mikheil Saakashvili to GD official Margvelashvili. Some analysts, however, have raised concerns over ongoing tensions between the UNM and GD, as well as Prime Minister and GD head Bidzini Ivanishvili’s announcement on November 2, 2013, that he will step down as the premier. In his victory speech on October 28, Margvelashvili reaffirmed Georgia’s Euro-Atlantic foreign policy orientation, including the pursuit of Georgia’s future membership in NATO and the EU. At the same time, he reiterated that GD would continue to pursue the normalization of ties with Russia. On October 28, 2013, the U.S. State Department praised the Georgian presidential election as generally democratic and expressing the will of the people, and as demonstrating Georgia’s continuing commitment to Euro-Atlantic integration. -

Georgia: an Emerging Governance: Problems and Prospects

Chapter 12 Georgia: An Emerging Governance: Problems and Prospects Dov Lynch Introduction Even if the Republic of Georgia has existed independently since 1992, it remains logical to discuss security sector governance as an emerging question. For much of the early 1990s, applying the notion of ‘security sector governance’ to a state at war and barely on its feet stretched the concept too far. The Georgian state embarked on a process of consolidation from 1995 onwards, initiated with the approval of a Constitution, and Georgia experienced thereafter several years of growth and relative political stability. In the late 1990s and early 2000s, the main lines of security sector reform were formulated on paper, and limited changes were effected in the Ministry of Defence and the armed forces. However, as a whole, security sector reform remains an emerging concern in so far as most of the work remains ahead for the new Georgian leadership in terms of addressing a distorted legacy, clarifying the scope of problems and prioritising amongst them, sketching out a coherent programme and implementing it. Two points should be noted from the outset. The first concerns the security sector in Georgia, the number of the agents involved and the nature of their interaction. Many have argued that the notion of ‘security sector reform’ is useful in drawing attention away from more limited understandings of military reform. Traditional discussions of civil- military relations tended to focus on the dyadic relationship between civilian political structures and a professional military agency. By contrast, reforming the security sector entails a more complex 249 understanding of these two poles and adds new actors to the picture1. -

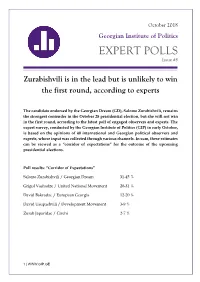

EXPERT POLLS Issue #8

October 2018 Georgian Institute of Politics EXPERT POLLS Issue #8 Zurabishvili is in the lead but is unlikely to win the first round, according to experts The candidate endorsed by the Georgian Dream (GD), Salome Zurabishvili, remains the strongest contender in the October 28 presidential election, but she will not win in the first round, according to the latest poll of engaged observers and experts. The expert survey, conducted by the Georgian Institute of Politics (GIP) in early October, is based on the opinions of 40 international and Georgian political observers and experts, whose input was collected through various channels. In sum, these estimates can be viewed as a “corridor of expectations” for the outcome of the upcoming presidential elections. Poll results: “Corridor of Expectations” Salome Zurabishvili / Georgian Dream 31-45 % Grigol Vashadze / United National Movement 20-31 % David Bakradze / European Georgia 12-20 % David Usupashvili / Development Movement 3-9 % Zurab Japaridze / Girchi 2-7 % 1 | WWW.GIP.GE Figure 1: Corridor of expectations (in percent) Who is going to win the presidential election? According to surveyed experts (figure 1), Salome Zurabishvili, who is endorsed by the governing Georgian Dream party, is poised to receive the most votes in the upcoming presidential elections. It is likely, however, that she will not receive enough votes to win the elections in the first round. According to the survey, Zurabishvili’s vote share in the first round of the elections will be between 31-45%. She will be followed by the United National Movement (UNM) candidate, Grigol Vashadze, who is expected to receive between 20-31% of votes. -

The Telegraph Names Georgia Top Travel Destination for UK Airlines

Issue no: 889 • OCTOBER 21 - 24, 2016 • PUBLISHED TWICE WEEKLY PRICE: GEL 2.50 In this week’s issue... Tbilisi Marathon to Take Place in City Center NEWS PAGE 2 Obama Calls Donald Trump’s Admiration of Putin ‘Unprecedented’ POLITICS PAGE 6 Separatist Commander, Alleged War Criminal Killed in Ukraine’s Donbass FOCUS POLITICS PAGE 7 ON EU RELATIONS & GEORGIAN VALUES Neuter and Spay Day with Ambassador Janos Herman discusses Mayhew International in Tbilisi EU-Georgia relations, values and bilateral cooperation PAGE 8 SOCIETY PAGE 10 Boris Akunin Meets Georgian The Telegraph Names Georgia Top Readers SOCIETY PAGE 10 Travel Destination for UK Airlines Tabliashvili’s Fairytale beyond he UK daily newspaper The Tel- Illusions egraph has named Georgia a top CULTURE PAGE 13 travel destination in an article titled: ‘17 amazing places UK air- lines should wake up and launch Product Tfl ights to.’ The article names 17 top destinations within Management 9,000 miles of London that need to be con- nected to Britain and can be reached from Workshop for Britain with just a single fl ight, and recommends British airline companies to launch direct fl ights Performing Arts there. The article recommends readers visit Geor- Professionals in gia “one of the oldest countries in the world,” and cites one of the tourists: Adjara "These days, its fi ne Art Nouveau buildings CULTURE PAGE 15 and pretty, traditional balconied houses are what some would call shabby chic. Yet new hotels and shopping malls are springing up and gentrifi cation is under way in its more historic districts. -

Russian Hybrid Tactics in Georgia

Russian Hybrid Tactics in Georgia Niklas Nilsson SILK ROAD PAPER January 2018 Russian Hybrid Tactics in Georgia Niklas Nilsson © Central Asia-Caucasus Institute & Silk Road Studies Program – A Joint Transatlantic Research and Policy Center American Foreign Policy Council, 509 C St NE, Washington D.C. Institute for Security and Development Policy, V. Finnbodavägen 2, Stockholm-Nacka, Sweden www.silkroadstudies.org “Russian Hybrid Tactics in Georgia” is a Silk Road Paper published by the Central Asia- Caucasus Institute and Silk Road Studies Program, Joint Center. The Silk Road Papers Series is the Occasional Paper series of the Joint Center, and addresses topical and timely subjects. The Joint Center is a transatlantic independent and non-profit research and policy center. It has offices in Washington and Stockholm and is affiliated with the American Foreign Policy Council and the Institute for Security and Development Policy. It is the first institution of its kind in Europe and North America, and is firmly established as a leading research and policy center, serving a large and diverse community of analysts, scholars, policy-watchers, business leaders, and journalists. The Joint Center is at the forefront of research on issues of conflict, security, and development in the region. Through its applied research, publications, research cooperation, public lectures, and seminars, it functions as a focal point for academic, policy, and public discussion regarding the region. The opinions and conclusions expressed in this study are those of -

Georgia: What Now?

GEORGIA: WHAT NOW? 3 December 2003 Europe Report N°151 Tbilisi/Brussels TABLE OF CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY AND RECOMMENDATIONS................................................. i I. INTRODUCTION .......................................................................................................... 1 II. BACKGROUND ............................................................................................................. 2 A. HISTORY ...............................................................................................................................2 B. GEOPOLITICS ........................................................................................................................3 1. External Players .........................................................................................................4 2. Why Georgia Matters.................................................................................................5 III. WHAT LED TO THE REVOLUTION........................................................................ 6 A. ELECTIONS – FREE AND FAIR? ..............................................................................................8 B. ELECTION DAY AND AFTER ..................................................................................................9 IV. ENSURING STATE CONTINUITY .......................................................................... 12 A. STABILITY IN THE TRANSITION PERIOD ...............................................................................12 B. THE PRO-SHEVARDNADZE -

Quarterly Report on the Political Situation in Georgia and Related Foreign Malign Influence

REPORT QUARTERLY REPORT ON THE POLITICAL SITUATION IN GEORGIA AND RELATED FOREIGN MALIGN INFLUENCE 2021 EUROPEAN VALUES CENTER FOR SECURITY POLICY European Values Center for Security Policy is a non-governmental, non-partisan institute defending freedom and sovereignty. We protect liberal democracy, the rule of law, and the transatlantic alliance of the Czech Republic. We help defend Europe especially from the malign influences of Russia, China, and Islamic extremists. We envision a free, safe, and prosperous Czechia within a vibrant Central Europe that is an integral part of the transatlantic community and is based on a firm alliance with the USA. Authors: David Stulík - Head of Eastern European Program, European Values Center for Security Policy Miranda Betchvaia - Intern of Eastern European Program, European Values Center for Security Policy Notice: The following report (ISSUE 3) aims to provide a brief overview of the political crisis in Georgia and its development during the period of January-March 2021. The crisis has been evolving since the parliamentary elections held on 31 October 2020. The report briefly summarizes the background context, touches upon the current political deadlock, and includes the key developments since the previous quarterly report. Responses from the third sector and Georgia’s Western partners will also be discussed. Besides, the report considers anti-Western messages and disinformation, which have contributed to Georgia’s political crisis. This report has been produced under the two-years project implemented by the Prague-based European Values Center for Security Policy in Georgia. The project is supported by the Transition Promotion Program of The Czech Ministry of Foreign Affairs and the Emerging Donors Challenge Program of the USAID. -

Georgia: Background and U.S

Georgia: Background and U.S. Policy Updated September 5, 2018 Congressional Research Service https://crsreports.congress.gov R45307 SUMMARY R45307 Georgia: Background and U.S. Policy September 5, 2018 Georgia is one of the United States’ closest non-NATO partners among the post-Soviet states. With a history of strong economic aid and security cooperation, the United States Cory Welt has deepened its strategic partnership with Georgia since Russia’s 2008 invasion of Analyst in European Affairs Georgia and 2014 invasion of Ukraine. U.S. policy expressly supports Georgia’s sovereignty and territorial integrity within its internationally recognized borders, and Georgia is a leading recipient of U.S. aid in Europe and Eurasia. Many observers consider Georgia to be one of the most democratic states in the post-Soviet region, even as the country faces ongoing governance challenges. The center-left Georgian Dream party has more than a three-fourths supermajority in parliament, allowing it to rule with only limited checks and balances. Although Georgia faces high rates of poverty and underemployment, its economy in 2017 appeared to enter a period of stronger growth than the previous four years. The Georgian Dream won elections in 2012 amid growing dissatisfaction with the former ruling party, Georgia: Basic Facts Mikheil Saakashvili’s center-right United National Population: 3.73 million (2018 est.) Movement, which came to power as a result of Comparative Area: slightly larger than West Virginia Georgia’s 2003 Rose Revolution. In August 2008, Capital: Tbilisi Russia went to war with Georgia to prevent Ethnic Composition: 87% Georgian, 6% Azerbaijani, 5% Saakashvili’s government from reestablishing control Armenian (2014 census) over Georgia’s regions of South Ossetia and Abkhazia, Religion: 83% Georgian Orthodox, 11% Muslim, 3% Armenian which broke away from Georgia in the early 1990s to Apostolic (2014 census) become informal Russian protectorates. -

Georgia Between Dominant-Power Politics, Feckless Pluralism, and Democracy Christofer Berglund Uppsala University

GEORGIA BETWEEN DOMINANT-POWER POLITICS, FECKLESS PLURALISM, AND DEMOCRACY CHRISTOFER BERGLUND UPPSALA UNIVERSITY Abstract: This article charts the last decade of Georgian politics (2003-2013) through theories of semi- authoritarianism and democratization. It first dissects Saakashvili’s system of dominant-power politics, which enabled state-building reforms, yet atrophied political competition. It then analyzes the nested two-level game between incumbents and opposition in the run-up to the 2012 parliamentary elections. After detailing the verdict of Election Day, the article turns to the tense cohabitation that next pushed Georgia in the direction of feckless pluralism. The last section examines if the new ruling party is taking Georgia in the direction of democratic reforms or authoritarian closure. nder what conditions do elections in semi-authoritarian states spur Udemocratic breakthroughs?1 This is a conundrum relevant to many hybrid regimes in the region of the former Soviet Union. It is also a ques- tion of particular importance for the citizens of Georgia, who surprisingly voted out the United National Movement (UNM) and instead backed the Georgian Dream (GD), both in the October 2012 parliamentary elections and in the October 2013 presidential elections. This article aims to shed light on the dramatic, but not necessarily democratic, political changes unleashed by these events. It is, however, beneficial to first consult some of the concepts and insights that have been generated by earlier research on 1 The author is grateful to Sten Berglund, Ketevan Bolkvadze, Selt Hasön, and participants at the 5th East Asian Conference on Slavic-Eurasian Studies, as well as the anonymous re- viewers, for their useful feedback. -

MINUTES of the XXXI I.C.S.C. CONGRESS of Almaty, Kazakhstan

MINUTES of the 31th I.C.S.C. CONGRESS held at the Congress Centre, Hotel & Resort Altyn Kargaly, Almaty, Kazakhstan, on Monday 1st October 2012, commencing at 09.45 hours AGENDA for the 31st I.C.S.C. Congress Almaty, Kazakhstan 01. I.C.S.C. President’s Opening Address 02. Welcome Speech by the Chess President of Kazakhstan, Mrs B. Begakhmet 03. Confirmation of the Election Committee 04. Confirmation of the I.C.S.C. Delegates’ Voting Powers 05. Additional Information for the Agenda (if any) 06. Admission of new National Association Federations (if any) 07. Confirmation of the 30th ICCD Congress Minutes, Estoril, Portugal 2010 08. I.C.S.C. Board Reports, 2010 & 2011 08.1 Matters Arising from the ICSC Board Reports 08.2 Confirmation of the ICSC Board Reports 09. Financial Report of the I.C.S.C. 09.1 Finance Committee - Report 09.2 Statement of Accounts 2010 09.3 Approval of the Financial Accounts 2010 09.4 Statement of Accounts 2011 09.5 Approval of the Financial Accounts 2011 10. Reports of I.C.S.C. Events 10.1 19th World Team Olympiads, Estoril 2010 10.2 39th F.I.D.E. Chess Olympiads, Khanty Mansiysk, Russia 2010 10.3 20th ICSC European Club Team Championships, Liverpool 2011 & 1st ICSC Open Team Event, Liverpool 2011 11. I.C.S.C. Reports 11.1 Archives Commission 11.2 Society of Friends of I.C.S.C. & Accounts 2010-11 12. Presentation of awards for I.C.S.C. Diplomas & Honours 13. Proposals & Motions 13.1 ICSC Member-Countries’ Motions 13.2 ICSC Board Motions 14. -

Georgia 2017 Human Rights Report

GEORGIA 2017 HUMAN RIGHTS REPORT EXECUTIVE SUMMARY The constitution provides for an executive branch that reports to the prime minister, a unicameral parliament, and a separate judiciary. The government is accountable to parliament. The president is the head of state and commander in chief. In September, a controversial constitutional amendments package that abolished direct election of the president and delayed a move to a fully proportional parliamentary election system until 2024 became law. Organization for Security and Cooperation in Europe (OSCE) observers termed the October local elections as generally respecting fundamental freedoms and reported candidates were able to campaign freely, while highlighting flaws in the election grievance process between the first and second rounds that undermined the right to effective remedy. They noted, too, that the entire context of the elections was shaped by the dominance of the ruling party and that there were cases of pressure on voters and candidates as well as a few violent incidents. OSCE observers termed the October 2016 parliamentary elections competitive and administered in a manner that respected the rights of candidates and voters but stated that the campaign atmosphere was affected by allegations of unlawful campaigning and incidents of violence. According to the observers, election commissions and courts often did not respect the principle of transparency and the right to effective redress between the first and second rounds, which weakened confidence in the election administration. In the 2013 presidential election, OSCE observers concluded the vote “was efficiently administered, transparent and took place in an amicable and constructive environment” but noted several problems, including allegations of political pressure at the local level, inconsistent application of the election code, and limited oversight of alleged campaign finance violations. -

Georgian Polyphony in a Century of Research: Foreword from the Editors

In: Echoes from Georgia: Seventeen Arguments on Georgian Polyphony. Rusudan Tsurtsumia and Joseph Jordania (Eds.). New York: Nova Science, 2010: xvii-xxii GEORGIAN POLYPHONY IN A CENTURY OF RESEARCH: FOREWORD FROM THE EDITORS Joseph Jordania and Rusudan Tsurtsumia This collection represents some of the most important authors and their writings about Georgian traditional polyphony for the last century. The collection is designed to give the reader the most possibly complete picture of the research on Georgian polyphony. Articles are given in a chronological order, and the original year of the publication (or completing the work) is given at every entry. As the article of Simha Arom and Polo Vallejo gives the comprehensive review of the whole collection, we are going instead to give a reader more general picture of research directions in the studies of Georgian traditional polyphony. We can roughly divide the whole research activities about Georgian traditional polyphony into six periods: (1) before the 1860s, (2) from the 1860s to 1900, (3) from the 1900s to 1930, (4) from the 1930s to 1950, (5) from the 1950s to 1990, and (6) from the 1990s till today. The first period (which lasted longest, which is usual for many time-based classifications), covers the period before the 1860s. Two important names from Georgian cultural history stand out from this period: Sulkhan-Saba Orbeliani (17th-18th centuries), and Ioane Bagrationi (beginning of the 18th-19th centuries). Both of them were highly educated people by the standards of their time. Ioane Bagrationi (1768-1830), known also as Batonishvili (lit. “Prince”) was the heir of Bagrationi dynasty of Georgian kings.