Journal of Perseverance and Academic Achievement for First Peoples

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Or, the Textual Production of Michif Voices As Cultural Weaponry

Intersections of Memory, Ancestral Language, and Imagination; or, the Textual Production of Michif Voices as Cultural Weaponry Pamela V. Sing n his overview of the historic origins in modern thought of ideas playing a central role in the current debate over matters of iden- tity and recognition, Charles Taylor emphasizes that, whether it is a Iquestion of individual or of collective identity, “we become full human agents, capable of understanding ourselves, and hence of defining our identity, through our acquisition of rich human languages of expression” (32). Languages, in this context, signify modes of expression used to iden- tify ourselves, including those of art and literature, and all evolve, are de- veloped, and are acquired in a dialogical manner — that is to say, through exchanges with others. By underscoring the socially derived character of identity, this perspective explains the importance of external recognition, both on an individual basis and on a cultural one. In this article, I intend to focus on an aesthetic that, grounded in memory, demonstrates and requests recognition for a particular type of “love of words.” The words in question belong to Michif, an oral ancestral language that, despite (or perhaps because of) its endangered status, proves to be a powerful identity symbol. Relegated to an underground existence during the latter part of the nineteenth century, the resurgence of Michif words and expressions in literary texts reminds the community to which they belong, and that they are telling (back) into existence, of its historic, cultural, and linguistic sources, thus re-laying claim to a specific and distinct, but unrecognized space on the Canadian word/landscape. -

Québec French in Florida: North American Francophone Language Practices on the Road

Québec French in Florida: North American Francophone Language Practices on the Road HÉLÈNE BLONDEAU Introduction Most of the sociolinguistic research on French in North America has focused on stable speech communities and long-established francophone groups in Canada or in the US, including Franco-Americans, Cajuns, Québécois and Acadians.1 However, since mobility has become an integral part of an increasingly globalized society, research on the language practices of transient groups of speakers is crucial for a better understanding of twenty-first-century francophone North America. The current article sheds light on the language practices of a group of speakers who experience a high degree of mobility and regular back-and-forth contact between francophone Canada and the US: francophone peoples of Québécois origin who move in and out of South Florida. For years, Florida has been a destination for many Canadians, some of whom have French as their mother tongue. A significant number of these people are part of the so-called “snowbird” population, a group that regularly travels south in an attempt to escape the rigorous northern winter. Snowbirds stay in the Sunshine State only temporarily. Others have established themselves in the US permanently, forming the first generation of Canado-Floridians, and another segment of the population is comprised of second-generation immigrants. By studying the language practices of such speakers, we can document the status of a mobile francophone group that has been largely under-examined in the body of research on French in North America. In this case, the mobility involves the crossing of national borders, and members of this community come in contact with English through their interactions with the American population in Florida. -

French in Québec: a Standard to Be Described and Uses to Be Prioritized

The French Language in Québec: 400 Years of History and Life Part Four II – French a Shared Language Chapter 13 – Which Language for the Future? 52. French in Québec: A Standard to be Described and Uses to Be Prioritized PIERRE MARTEL and HÉLÈNE CAJOLET-LAGANIÈRE The Evolution of the Standard for Written and Spoken French in Québec For more than two centuries, Québécois have lived in a twofold linguistic insecurity. On the one hand, French was rendered a second-class language by English, which was widely dominant in a number of social spheres and, on the other, its status was undermined compared to the French of France, the one and only benchmark. The “ Joual dispute” of the 1960s and 1970s crystallized opinions around a simplistic alternative: either the language of Québécois was the French of France (most usually termed International French 1, chiefly in order to indicate no dependence on the mother country), in which case every effort would have to be made to conform to it on every point, or else theirs was the popular language of those who were little educated, that is, vernacular speech, stigmatized by the term “ Joual ,” which some associated with the very identity of the Québécois. This black and white representation of the state of our language was ideological and unrealistic. It was as if French was made up of only a “standard” level, the correct written usage, and as if Québec French had only one language level, the vernacular, and even the lax and vulgar language. The Charter of the French Language, promulgated in 1977, contained no provision aimed at defining “French in Québec,” the “standard” or the “quality of the language.” However, the 1 The French Language in Québec: 400 Years of History and Life Part Four II – French a Shared Language Chapter 13 – Which Language for the Future? Policy Statement that gave birth to the Charter drew attention to the necessity of having a quality language. -

Language Projections for Canada, 2011 to 2036

Catalogue no. 89-657-X2017001 ISBN 978-0-660-06842-8 Ethnicity, Language and Immigration Thematic Series Language Projections for Canada, 2011 to 2036 by René Houle and Jean-Pierre Corbeil Release date: January 25, 2017 How to obtain more information For information about this product or the wide range of services and data available from Statistics Canada, visit our website, www.statcan.gc.ca. You can also contact us by email at [email protected] telephone, from Monday to Friday, 8:30 a.m. to 4:30 p.m., at the following numbers: • Statistical Information Service 1-800-263-1136 • National telecommunications device for the hearing impaired 1-800-363-7629 • Fax line 1-514-283-9350 Depository Services Program • Inquiries line 1-800-635-7943 • Fax line 1-800-565-7757 Standards of service to the public Standard table symbols Statistics Canada is committed to serving its clients in a prompt, The following symbols are used in Statistics Canada reliable and courteous manner. To this end, Statistics Canada has publications: developed standards of service that its employees observe. To . not available for any reference period obtain a copy of these service standards, please contact Statistics .. not available for a specific reference period Canada toll-free at 1-800-263-1136. The service standards are ... not applicable also published on www.statcan.gc.ca under “Contact us” > 0 true zero or a value rounded to zero “Standards of service to the public.” 0s value rounded to 0 (zero) where there is a meaningful distinction between true zero and the value that was rounded p preliminary Note of appreciation r revised Canada owes the success of its statistical system to a x suppressed to meet the confidentiality requirements long-standing partnership between Statistics Canada, the of the Statistics Act citizens of Canada, its businesses, governments and other E use with caution institutions. -

Portrait Des Plages De La Rive Nord De L'estuaire

PORTRAIT DES PLAGES DE LA RIVE NORD DE L’ESTUAIRE, Inventaire des problématiques et recommandations Comité ZIP de la rive nord de l’estuaire Octobre 2009 Ce document est imprimé sur du papier québécois Cascade Nouvelle vie DP100TM recyclé. Ainsi, aucun arbre n’a été coupé pour le produire. Il provient à 100 % de papier recyclé post- consommation en tenant compte de toutes les étapes de transformation. À l’usine, le procédé de désencrage sans clore utilise 80% moins d'eau que la moyenne de l’industrie canadienne lors de la fabrication du papier. Ce papier est aussi accrédité Éco-Logo (PCE-77) par le programme Choix environnemental d’Environnement Canada. I Équipe de réalisation Méthodologie et travaux terrain : o Marie-Hélène Cloutier, chargée de projet, Comité ZIP de la rive nord de l’estuaire, biologiste, B. Sc. o Jean-François Brisard, stagiaire par l’intermédiaire de l’Office franco-québécois pour la jeunesse o Corine Trentin, biologiste stagiaire par l’intermédiaire de l’Office franco-québécois pour la jeunesse o Valérie Desrochers, géographe stagiaire de l’université de Rimouski au Québec Rédaction : o Marie-Hélène Cloutier, chargée de projet, Comité ZIP de la rive nord de l’estuaire, biologiste, B. Sc. o Corine Trentin, biologiste stagiaire par l’intermédiaire de l’Office franco-québécois pour la jeunesse o Émilie Lapointe, chargée de projet, Comité ZIP de la rive nord de l’estuaire, biologiste, B. Sc. Cartographie : o Dominic Francoeur, Comité ZIP de la rive nord de l’estuaire Comité d’orientation : o Marc Pagé, Parc marin du Saguenay-Saint-Laurent o Sophie Roy, ministère des Pêches et Océans Canada o Claude Leblond, Corporation de développement du secteur des Panoramas o Frédéric Bénichou, Parc nature de Pointe-au-outardes Pour citation Comité ZIP de la rive nord de l’estuaire, 2009, Portrait des plages de la rive nord de l’estuaire, Inventaire des problématiques et recommandations, 117 p. -

Language Rights and Quebec Bill 101

Case Western Reserve Journal of International Law Volume 10 Issue 2 Article 11 1978 Language Rights and Quebec Bill 101 Clifford Savren Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarlycommons.law.case.edu/jil Part of the International Law Commons Recommended Citation Clifford Savren, Language Rights and Quebec Bill 101, 10 Case W. Res. J. Int'l L. 543 (1978) Available at: https://scholarlycommons.law.case.edu/jil/vol10/iss2/11 This Note is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Journals at Case Western Reserve University School of Law Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Case Western Reserve Journal of International Law by an authorized administrator of Case Western Reserve University School of Law Scholarly Commons. 1978] Language Rights and Quebec Bill 101 INTRODUCTION N THE WORDS of Maclean's, Canada's news magazine: "On November 15, 1976, Canada entered a new era. In the year since, the unthinkable has suddenly become normal and the impossible sud- denly conceivable."' The Quebec provincial elections of November 1976 brought to power a party whose primary goal is the separation of the Province from the rest of Canada and the establishment of Quebec as a sovereign independent state. 2 The election victory of the Parti Qu~b~cois under the leadership of Ren6 Lvesque has forced Cana- dians across the political spectrum to face some difficult questions regarding the essence of Canadian identity and the feasibility of for- mulae which more effectively could accomodate the unique character of Quebec, the only Canadian province with a predominantly French- speaking population.' 1759 brought the defeat by the British of the 74,000 French in- habitants of Quebec. -

Région 09 : Côte-Nord MRC Et Agglomérations Ou Municipalités Locales Exerçant Certaines Compétences De MRC

Région 09 : Côte-Nord MRC et agglomérations ou municipalités locales exerçant certaines compétences de MRC Territoire ou Population Superficie Code municipalité régionale de comté (2010) km2 982 Basse-Côte-Nord (hors MRC) 4 517 6 156.64 972 Caniapiscau 3 044 81 184.15 950 La Haute-Côte-Nord 11 619 12 508.69 960 Manicouagan 30 232 39 462.09 981 Minganie 5 238 128 492.36 971 Sept-Rivières 33 311 32 153.95 Hors MRC (autochtones) 8 547 323.95 96 508 300 281.83 972 Caniapiscau Tracé de 1927 du Conseil privé (non définitif) 981 971 Minganie Sept-Rivières 982 960 Basse-Côte-Nord Manicouagan Frontière provinciale Frontière internationale 950 La Haute-Côte-Nord Région administrative Municipalité régionale de comté Territoire Direction du Bureau municipal, de la géomatique et de la statistique 0 50 100 200 Kilomètres Mars 2010 © Gouvernement du Québec Basse-Côte-Nord 982 (Territoire hors MRC) Dési- Population Superficie Dési- Population Superficie Code Municipalité gnation (2010) km2 Code Municipalité gnation (2010) km2 98005 Blanc-Sablon M 1 258 254.49 98014 Gros-Mécatina M 551 961.46 98010 Bonne-Espérance M 802 721.28 98012 Saint-Augustin M 883 1 435.82 98015 Côte-Nord-du-Golfe-du-Saint-Laurent M 1 023 2 783.59 Total 4 517 6 156.64 Hors MRC (autochtones) ¹ 98804 La Romaine R 976 0.41 ¹ Non visé par le décret de population Blanc- Sablon, M Bonne- Espérance, M Pakuashipi, EI Saint- Augustin, M Gros- Mécatina, M Côte-Nord-du-Golfe- du-Saint-Laurent, M La Romaine, R Population (Décret 2010) 0 h. -

Loan Verb Integration in Michif

journal of language contact 12 (2019) 27-51 brill.com/jlc Loan Verb Integration in Michif Anton Antonov inalco-crlao, paris [email protected] Abstract This paper looks at the different ways French (and English) loan verbs are being inte- grated in Michif, a mixed language (the noun system is French, the verbal one is Cree) based upon two dictionaries of the language. The detailed study of the available data has shown that loan verbs are almost exclusively assigned to the vai class, i.e. a class of verbs whose single core argument is animate. This seems natural enough given that the overwhelming majority of them do have an animate core participant in the donor language as well. Still, quite a few of them can be transitive. This is accounted for by claiming that vai is the most ‘neutral’ inflectional class of Cree as far as morphology and argument structure are concerned as verbs in this class can be syntactically both intransitive and transitive. Finally, all of the loan verbs examined have Cree equivalents and so the claim that they were borrowed because of the lack of a corresponding Cree verb in the language is difficult to accept at face value. Keywords loan verbs – valency – transitivity – animacy – direct/inverse – hierarchical agreement – Algonquian – Cree – Michif 1 Introduction This paper deals with French and English loan verbs in Michif, and in particu- lar the ways in which they have been integrated into the almost exclusively Cree (i.e. Algonquian) verbal system of that language. It is especially con- cerned with the ways in which the argument structure of the original verb has been mapped onto the existing valency patterns. -

INTRODUCTION: When Listening to Both French and Quebec French, It Is Likely That You Will Notice a Difference in the Way They Sp

French and Quebec French: Are They the Same Language? INTRODUCTION: When listening to both French GRAMMATICAL DIFFERENCES: PHONOLOGICAL DIFFERENCES: -Quebec French is characterized by a “freer” use of Quebec French has more vowel sounds than and Quebec French, it is likely that you will notice grammatical rules. For instance many Canadian French Parisian French. For a difference in the way they speak, whether you suppress articles: “à ce soir” (literal translation:" see you instance, /a/ and /ɑ/, /ɛ/ and /ɛː/, /ø/ and /ə/, know French or not. While the difference in accent this night"), would become “à soir”, dropping the article /ɛ/̃ and /œ̃ / are pronounced different in Quebec is the most noticeable difference between both “ce" ("this"). French while it is not the case anymore in standard French. languages, linguists argue that there are way more -Many Québec French also remove prepositions from features that differentiate French and Québec their utterances. For French. example,:"voici le chien dont tu dois t’occuper" (this is the dog you must take care of"), would become: "voici le chien à t'occuper", (this is the dog to take care of). EXAMPLE OF THE DIFFERENCES QUICK HISTORICAL FACTS: 7,2 million Canadians are French speaking natives (20% of the Canadian population). Although English is the most spoken language u Canada, Quebec French VOCABULARY DIFFERENCES: is known for being a French speaking province since the 17th century. While at the beginning of the 1800s, Canadian French There is a huge paradox regarding anglicism in Quebec was identical to Parisian French, it started to change during French. -

French Language in the Americas: Quebec, Acadia, and Louisiana

Scholarly Horizons: University of Minnesota, Morris Undergraduate Journal Volume 5 Issue 2 Article 4 June 2018 French Language in the Americas: Quebec, Acadia, and Louisiana Katelyn Gross University of Minnesota, Morris Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.morris.umn.edu/horizons Part of the French Linguistics Commons Recommended Citation Gross, Katelyn (2018) "French Language in the Americas: Quebec, Acadia, and Louisiana," Scholarly Horizons: University of Minnesota, Morris Undergraduate Journal: Vol. 5 : Iss. 2 , Article 4. Available at: https://digitalcommons.morris.umn.edu/horizons/vol5/iss2/4 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at University of Minnesota Morris Digital Well. It has been accepted for inclusion in Scholarly Horizons: University of Minnesota, Morris Undergraduate Journal by an authorized editor of University of Minnesota Morris Digital Well. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Gross: French Language in the Americas Katelyn Gross 1 French Language in the Americas: Quebec, Acadia, and Louisiana Katelyn Gross The French language underwent many changes between the development of French from Latin, to Old French, and to Middle French. French would continue to develop inside of France thereafter, but the French language would also be exported to other parts of the world and those varieties of French would have their own characteristic changes. French explorers and colonizers moved into the Americas, permanently settling what is today Quebec, many parts of Canada, and Louisiana in the United States. In this paper, I will focus on the linguistic differences between metropolitan France and French spoken in Quebec, Acadia, and Louisiana. -

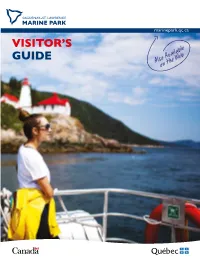

Visitor's Guide

VISITOR’S GUIDE Also Available on the Web WELCOME TO THE SAGUENAY–ST. LAWRENCE MARINE PARK! PHOTO 1 PHOTO The park protects an exceptional marine area from A TREAT ON LAND AND AT SEA surface to seafloor. More than 2,000 wild species have been sighted within its boundaries, ranging from microscopic algae to the gigantic blue whale. You will be unequivocally charmed by the Park’s scenic The St. Lawrence beluga whale is its most famous resident. beauty. Climb into a kayak or set sail. Take a cruise up the Fjord or to the islands of the St. Lawrence. Admire PAY A VISIT TO WHALE COUNTRY the colours of the seafloor while diving or on a high- The Marine Park is one of the best places in the world definition screen. Visit Discovery Network shore-based to observe whales. Watch them break the surface and sites: take advantage of spectacular viewpoints, roam listen for their powerful blows from established coastal hiking trails or exhibits and get caught up in fascinating sites or from aboard tour-operator vessels. tales. WHALES AND SEALS OF THE SAGUENAY–ST. LAWRENCE MARINE PARK The beluga whale and harbour seal are the only marine mammals that live year round in the St. Lawrence Estuary. The others migrate between the marine park, where they come to feed, and their mating grounds outside park boundaries. Would you be able to identify them by their outline? To learn more about whales, visit marinepark.qc.ca/get-to-know/ 2 THE ESSENTIALS PHOTO 2 PHOTO 3 PHOTO WHALE WATCHING WHALE WATCHING FROM SHORE BY BOAT Keep your eyes peeled and your ears open while out walking, biking What fun it is to hear a whale blow or to catch a glimpse of one or driving along the Marine Park’s shorelines! You might well glimpse of these incredible animals at the surface! Take in the fascinating or hear beluga, minke or fin whales, or possibly harbour porpoises, spectacle of marine animals from aboard a boat. -

Language Education, Canadian Civic Identity and the Identities of Canadians

LANGUAGE EDUCATION, CANADIAN CIVIC IDENTITY AND THE IDENTITIES OF CANADIANS Guide for the development of language education policies in Europe: from linguistic diversity to plurilingual education Reference study Stacy CHURCHILL Ontario Institute for Studies in Education, University of Toronto Language Policy Division DG IV – Directorate of School, Out-of-School and Higher Education Council of Europe, Strasbourg French edition: L’enseignement des langues et l’identité civique canadienne face à la pluralité des identités des Canadiens The opinions expressed in this work are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the official policy of the Council of Europe. All correspondence concerning this publication or the reproduction or translation of all or part of the document should be addressed to the Director of School, Out- of-School and Higher Education of the Council of Europe (F-67075 Strasbourg Cedex). The reproduction of extracts is authorised, except for commercial purposes, on condition that the source is quoted. © Council of Europe, 2003 TABLE OF CONTENTS Preface .........................................................................................................................5 1. Introduction.........................................................................................................7 2. Linguistic And Cultural Identities In Canada ......................................................8 3. Creating Identity Through Official Bilingualism...............................................11 3.1. Origins of Federal