Deliberation in New Zealand's House of Representatives

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Sea Change the Birth of a New Marine Institute

ET LABORE MAGAZINE OF THE UNIVERSITY OF AUCKLAND SPRING 2004 SEA CHANGE THE BIRTH OF A NEW MARINE INSTITUTE SELLING OUR EXPERTISE TOP TERTIARY TEACHERS MAINTAINING THE BRAIN WHAT DRIVES OUR DONORS? Be in to win an objet d’art with your new home loan. And a trip around the world to find it. Buying a home is one of the most exciting purchases you will ever make but it can also be one of the most overwhelming. Fixed or floating, one year or two? There are so many decisions to make and so many choices – how do you know what is best for your personal circumstances? At HSBC we draw on our worldwide resources and local knowledge to help you choose the right home loan for you. We recognise that everyone is different and therefore offer a flexible choice of options at extremely competitive rates that can be tailored to your individual needs. To celebrate your individuality we’re offering you the chance to enter a draw to choose an objet d’art that’s uniquely you and a trip around the world to find it – when you select your new home loan and draw it down by 28 February 2005. For a competition entry form and more details - HSB 2827 Visit your nearest branch 0800 88 86 86 www.hsbc.co.nz Issued by The Hongkong and Shanghai Banking Corporation Limited, incorporated in Hong Kong, New Zealand branch. Lending criteria and terms and conditions apply to all our home loans (including a minimum home loan value). Lenders Mortgage Insurance or an application fee may apply where you are borrowing more than 80% of a property’s value. -

A Transcript of Prime Minister John Key's Speech to the Canterbury Employers' Chamber of Commerce Function, 2Nd July 2015. Good

A transcript of Prime Minister John Key's speech to the Canterbury Employers' Chamber of Commerce function, 2nd July 2015. Good afternoon. Thank you Peter for that warm welcome and for the Chamber's hosting of this event. It's good to see so many of you here today. Can I start by acknowledging Mayor Lianne Dalziel and other local body representatives from around the region. Just as central government has to make some tough decisions and trade-offs, so too do councils as we work together to rebuild this city. Together, we're making significant progress. Although, of course, there is still much to do. I'd also like to acknowledge my ministerial colleagues Gerry Brownlee, Amy Adams and Nicky Wagner. Gerry has provided strong leadership in overseeing what continues to be one of New Zealand's largest and most complex undertakings. Most recently he has been turning his mind to where we go following the expiry of the special earthquake recovery laws next April. I'll have some more to say about that in a few minutes. As we've said before, the estimated cost of the rebuild is around $40 billion. As a proportion of the economy, this makes it one of the most expensive natural disasters in the developed world. So thanks to all of you here who have worked so hard since the first earthquake in September 2010. I want to start today by talking about the economy and the significant contribution Canterbury makes to it. A strong and growing economy allows us to provide essential public services like hospitals and schools, and support our most vulnerable families. -

Annual Report for the Year Ended 30 June 2012

A.2 Annual Report for the year ended 30 June 2012 Parliamentary Service Commission Te Komihana O Te Whare Pāremata Presented to the House of Representatives pursuant to Schedule 2, Clause 11 of the Parliamentary Service Act 2000 About the Parliamentary Service Commission The Parliamentary Service Commission (the Commission) is constituted under the Parliamentary Service Act 2000. The Commission has the following functions: • to advise the Speaker on matters such as the nature and scope of the services to be provided to the House of Representatives and members of Parliament; • recommend criteria governing funding entitlements for parliamentary purposes; • recommend persons who are suitable to be members of the appropriations review committee; • consider and comment on draft reports prepared by the appropriations review committees; and • to appoint members of the Parliamentary Corporation. The Commission may also require the Speaker or General Manager of the Parliamentary Service to report on matters relating to the administration or the exercise of any function, duty, or power under the Parliamentary Service Act 2000. Membership The membership of the Commission is governed under sections 15-18 of the Parliamentary Service Act 2000. Members of the Commission are: • the Speaker, who also chairs the Commission; • the Leader of the House, or a member of Parliament nominated by the Leader of the House; • the Leader of the Opposition, or a member of Parliament nominated by the Leader of the Opposition; • one member for each recognised party that is represented in the House by one or more members; and • an additional member for each recognised party that is represented in the House by 30 or more members (but does not include among its members the Speaker, the Leader of the House, or the Leader of the Opposition). -

The Comparative Politics of E-Cigarette Regulation in Australia, Canada and New Zealand by Alex C

Formulating a Regulatory Stance: The Comparative Politics of E-Cigarette Regulation in Australia, Canada and New Zealand by Alex C. Liber A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (Health Services Organizations and Policy) in The University of Michigan 2020 Doctoral Committee: Professor Scott Greer, Co-Chair Assistant Professor Holly Jarman, Co-Chair Professor Daniel Béland, McGill University Professor Paula Lantz Alex C. Liber [email protected] ORCID iD: 0000-0001-7863-3906 © Alex C. Liber 2020 Dedication For Lindsey and Sophia. I love you both to the ends of the earth and am eternally grateful for your tolerance of this project. ii Acknowledgments To my family – Lindsey, you made the greatest sacrifices that allowed this project to come to fruition. You moved away from your family to Michigan. You allowed me to conduct two months of fieldwork when you were pregnant with our daughter. You helped drafts come together and were a constant sounding board and confidant throughout the long process of writing. This would not have been possible without you. Sophia, Poe, and Jo served as motivation for this project and a distraction from it when each was necessary. Mom, Dad, Chad, Max, Julian, and Olivia, as well as Papa Ernie and Grandma Audrey all, helped build the road that I was able to safely walk down in the pursuit of this doctorate. You served as role models, supports, and friends that I could lean on as I grew into my career and adulthood. Lisa, Tony, and Jessica Suarez stepped up to aid Lindsey and me with childcare amid a move, a career transition, and a pandemic. -

National Spokespeople Chart (190118)

LEADER DEPUTY LEADER SIMON BRIDGES PAULA BENNETT AMY ADAMS KANWAL SINGH BAKSHI MAGGIE BARRY ANDREW BAYLY DAVID BENNETT DAN BIDOIS CHRIS BISHOP SIMEON BROWN Tauranga • National Upper Harbour Selwyn • Finance List MP • Internal Affairs North Shore • Seniors Hunua • Building and Hamilton East Northcote Hutt South Pakuranga Security and Social Investment & Social Shadow Attorney-General Assoc. Justice Veterans • Assoc. Health Construction • Revenue Corrections Assoc. Workplace Relations Police • Youth Assoc. Education • Assoc. Tertiary Intelligence Services • Drug Reform • Women Assoc. Finance Land Information and Safety Education, Skills & Employment Assoc. Infrastructure GERRY BROWNLEE DAVID CARTER JUDITH COLLINS JACQUI DEAN MATT DOOCEY SARAH DOWIE ANDREW FALLOON PAUL GOLDSMITH NATHAN GUY JO HAYES Ilam • Shadow Leader of List MP Papakura • Housing & Urban Waitaki Waimakariri Invercargill Rangitata • Regional List MP • Economic & Regional Otaki • Agriculture List MP • Whānau Ora the House • GCSB • NZSIS State-Owned Enterprises Development • Infrastructure Local Government Mental Health Conservation Development (South Island) Development • Transport Biosecurity • Food Safety Māori Education America’s Cup Planning (RMA Reform) Small Business Junior Whip Assoc. Arts, Culture & Heritage HARETE HIPANGO BRETT HUDSON NIKKI KAYE MATT KING NUK KORAKO BARBARA KURIGER DENISE LEE MELISSA LEE AGNES LOHENI TIM MACINDOE Whanganui List MP • Commerce & Auckland Central Northland List MP • Māori Development Taranaki - King Country Maungakiekie List MP • Broadcasting, -

Politician Overboard: Jumping the Party Ship

INFORMATION, ANALYSIS AND ADVICE FOR THE PARLIAMENT INFORMATION AND RESEARCH SERVICES Research Paper No. 4 2002–03 Politician Overboard: Jumping the Party Ship DEPARTMENT OF THE PARLIAMENTARY LIBRARY ISSN 1328-7478 Copyright Commonwealth of Australia 2003 Except to the extent of the uses permitted under the Copyright Act 1968, no part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means including information storage and retrieval systems, without the prior written consent of the Department of the Parliamentary Library, other than by Senators and Members of the Australian Parliament in the course of their official duties. This paper has been prepared for general distribution to Senators and Members of the Australian Parliament. While great care is taken to ensure that the paper is accurate and balanced, the paper is written using information publicly available at the time of production. The views expressed are those of the author and should not be attributed to the Information and Research Services (IRS). Advice on legislation or legal policy issues contained in this paper is provided for use in parliamentary debate and for related parliamentary purposes. This paper is not professional legal opinion. Readers are reminded that the paper is not an official parliamentary or Australian government document. IRS staff are available to discuss the paper's contents with Senators and Members and their staff but not with members of the public. Published by the Department of the Parliamentary Library, 2003 I NFORMATION AND R ESEARCH S ERVICES Research Paper No. 4 2002–03 Politician Overboard: Jumping the Party Ship Sarah Miskin Politics and Public Administration Group 24 March 2003 Acknowledgments I would like to thank Martin Lumb and Janet Wilson for their help with the research into party defections in Australia and Cathy Madden, Scott Bennett, David Farrell and Ben Miskin for reading and commenting on early drafts. -

Stakeholder Engagement Strategies for Designating New Zealand Marine Reserves

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by ResearchArchive at Victoria University of Wellington Stakeholder engagement strategies for designating New Zealand marine reserves: A case study of the designation of the Auckland Islands (Motu Maha) Marine Reserve and marine reserves designated under the Fiordland (Te Moana o Atawhenua) Marine Management Act 2005 Thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the Degree of Master of Development Studies at Victoria University of Wellington By James Mize Victoria University of Wellington 2007 "The use of sea and air is common to all; neither can a title to the ocean belong to any people or private persons, forasmuch as neither nature nor public use and custom permit any possession thereof." -Elizabeth I of England (1533-1603) "It is a curious situation that the sea, from which life first arose should now be threatened by the activities of one form of that life. But the sea, though changed in a sinister way, will continue to exist; the threat is rather to life itself." - Rachel Carson , (1907-1964) The Sea Around Us , 1951 ii Abstract In recent years, marine reserves (areas of the sea where no fishing is allowed) have enjoyed increased popularity with scientists and agencies charged with management of ocean and coastal resources. Much scientific literature documents the ecological and biological rationale for marine reserves, but scholars note the most important consideration for successful establishment reserves is adequate involvement of the relevant stakeholders in their designation. Current guidance for proponents of marine reserves suggests that to be successful, reserves should be designated using “bottom-up” processes favouring cooperative management by resource-dependent stakeholders, as opposed to “top-down” approaches led by management agencies and international conservation organizations. -

Issue 17 2017

Shifting Stones Ruckus over Ruggers Centre Stage Catriona Britton examines the harm being done Mark Fullerton talks SKY TV’s very bad A chat with New Zealand theatre company to an historical site manners Indian Ink [1] ISSUE SEVENTEEN CONTENTS 7 NEWS 10 COMMUNITY MED STUDENTS SICK OF LOAN CAP THE LIMITS OF FREEDOM OF SPEECH Medical students aren’t getting graduation caps because of A look at how New Zealand student loan caps deals with censorship 13 LIFESTYLE 16 FEATURES SPRING AWAKENING TIT FOR TATT We’ve got tips on how to make your garden bloomin’ beautiful Olivia Stanley ponders society’s this Spring view of tattoos 31 ARTS 34 COLUMNS ONE MOVIE TO RULE THEM ALL A SHADOW OF HER FORMER SELF A definitive ranking of the LOTR and Hobbit movie Caitlin Abley has had a gutsful trilogies of Shadows cuisine New name. Same DNA. ubiq.co.nz 100% Student owned - your store on campus [3] NOTICE OF POLLING TIMES FOR THE 2018 AUSA EXECUTIVE & 2017 ENVIRONMENTAL AFFAIRS OFFICER ELECTIONS ONLINE ELECTIONS WILL BE HELD FROM 9AM ON TUESDAY 22ND TO 4PM ON THURSDAY 24TH OF AUGUST 2017 TO VOTE GO TO: WWW.AUSA.ORG.NZ/VOTE ONLY AUSA MEMBERS CAN VOTE, HOWEVER YOU CAN SIGN UP ONLINE WHEN YOU VOTE. A POLLING BOOTH WILL BE AVAILABLE AT AUSA RECEPTION IF YOU DO NOT HAVE ACCESS TO ONLINE VOTING. LIFE MEMBERS WILL NEED TO GO TO AUSA RECEPTION TO VOTE. BOB LACK AUSA RETURNING OFFICER NOTICE OF POLLING TIMES FOR THE EDITORIAL 2018 AUSA EXECUTIVE Catriona Britton Samantha Gianotti & 2017 ENVIRONMENTAL AFFAIRS OFFICER ELECTIONS Giving a Shit ONLINE ELECTIONS WILL BE HELD FROM 9AM ON TUESDAY 22ND Last Monday morning, one Craccum Editor was make it into the top ten that God cast down on with deliberation and confidence. -

Amendment Bill

Crimes (Provocation Repeal) Amendment Bill Government Bill As reported from the Justice and Electoral Committee Commentary Recommendation The Justice and Electoral Committee has examined the Crimes (Provocation Repeal) Amendment Bill and recommends that it be passed with the amendments shown. Introduction This bill as introduced proposes to abolish the partial defence of provocation, by repealing sections 169 and 170 of the Crimes Act 1961. Section 169 of the Crimes Act provides that culpable homicide that would otherwise be murder may be reduced to manslaughter if the person who caused the death did so under provocation as defined by the section; section 170 provides that an illegal arrest does not necessarily reduce the offence of murder to manslaughter, but if the offender knows of the illegality then it may be evidence of provoca- tion. 64—2 Crimes (Provocation Repeal) 2 Amendment Bill Commentary Partial defence of provocation abolished We note that the codification of the partial defence of provocation was a reflection of the existing common law partial defence. For the avoidance of doubt, we recommend inserting new clause 5 to make it clear that the common law partial defence would also be abolished by the bill. This would avoid the possibility of defence counsel relying on the defence, so far as it has any effect as a principle of the common law of New Zealand, in cases of culpable homicide. Issues raised in submissions Although we do not recommend amendments as a result of submis- sions we received on the bill, we considered it would be useful to discuss some of the issues that were raised. -

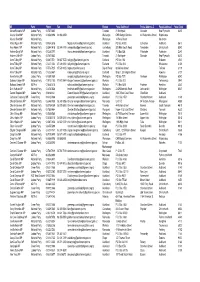

Members Offices As at 21 June 2016.Xlsx

MP Party Phone Fax Email Region Postal Address 1 Postal Address 2 Postal Address 3 Postal Code Adrian Rurawhe MP Labour Party 06 757 5662 Taranaki 21 Northgate Strandon New Plymouth 4312 Alastair Scott MP National Party 06 858 8196 06 858 8459 Wairarapa CHB Budget Services 43 Ruataniwha Street Waipukurau Alastair Scott MP National Party Wairarapa 14 Perry Street Masterton Alfred Ngaro MP National Party 09 834 3676 [email protected] Auckland PO Box 83200 Edmonton Auckland 0610 Amy Adams MP National Party 03 344 0418 03 344 0419 [email protected] Canterbury 829 Main South Road Templeton Christchurch 8042 Andrew Bayly MP National Party 09 238 5977 [email protected] Auckland P O Box 528 Pukekohe Pukekohe 2340 Andrew Little MP Labour Party 06 757 5662 Taranaki 21 Northgate Strandon New Plymouth 4312 Anne Tolley MP National Party 06 867 7571 06 867 7572 [email protected] Eastland PO Box 106 Gisborne 4040 Anne Tolley MP National Party 07 307 1254 07 308 0351 [email protected] Eastland P.O. Box 216 Whakatane 3158 Anne Tolley MP National Party 07 573 7125 07 573 9125 [email protected] Bay of Plenty 68 Jellicoe Street Te Puke 3119 Anne Tolley MP National Party 07 323 6487 [email protected] Eastland Shop 1, 35 Islington Street Kawerau 3127 Annette King MP Labour Party 04 389 0989 [email protected] Wellington PO Box 7071 Newtown Wellington 6242 Barbara Kuriger MP National Party 07 870 1005 07 870 3904 [email protected] Waikato P.O. -

House of Representatives List of Members

FORTY-EIGHTH PARLIAMENT OF NEW ZEALAND ___________ HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES ____________ LIST OF MEMBERS 1 September 2008 MEMBERS OF PARLIAMENT Member Electorate/List Party Postal Address and E-mail Address Phone and Fax Anderton, Hon Jim Freepost Parliament, (04) 470 6550 Leader, Progressive Private Bag 18 888, Parliament Buildings Fax (04) 495 8441 Minister of Agriculture Wellington 6160 Minister for Biosecurity Minister of Fisheries Wigram Progressive [email protected] Minister of Forestry Minister responsible for the 296 Selwyn St, Spreydon, Christchurch (03) 365 5459 Public Trust PO Box 33 164, Barrington, Christchurch Fax (03) 365 6173 Associate Minister of Health [email protected] Associate Minister for Tertiary Education Freepost Parliament (04) 471 9357 Private Bag 18 888, Parliament Buildings Fax (04) 437 6447 Ardern MP, Shane Taranaki – King Country National Wellington 6160 [email protected] Freepost Parliament (04) 470 6936 Private Bag 18 888, Parliament Buildings Fax (04) 439 6445 Auchinvole, Chris List National Wellington 6160 [email protected] (04) 470 6572 Barker, Hon Rick Freepost Parliament Fax (04) 472 8036 Minister of Internal Affairs Private Bag 18 888, Parliament Buildings Minister of Civil Defence Wellington 6160 Minister for Courts List Labour [email protected] Minister of Veterans’ Affairs Associate Minister of Justice PO Box 1245, Hastings (06) 876 8966 Fax (06) 876 4908 Freepost Parliament (04) 471 9906 Private Bag 18 888, Parliament Buildings Fax (04) -

New Zealand Hansard Precedent Manual

IND 1 NEW ZEALAND HANSARD PRECEDENT MANUAL Precedent Manual: Index 16 July 2004 IND 2 ABOUT THIS MANUAL The Precedent Manual shows how procedural events in the House appear in the Hansard report. It does not include events in Committee of the whole House on bills; they are covered by the Committee Manual. This manual is concerned with structure and layout rather than text - see the Style File for information on that. NB: The ways in which the House chooses to deal with procedural matters are many and varied. The Precedent Manual might not contain an exact illustration of what you are looking for; you might have to scan several examples and take parts from each of them. The wording within examples may not always apply. The contents of each section and, if applicable, its subsections, are included in CONTENTS at the front of the manual. At the front of each section the CONTENTS lists the examples in that section. Most sections also include box(es) containing background information; these boxes are situated at the front of the section and/or at the front of subsections. The examples appear in a column format. The left-hand column is an illustration of how the event should appear in Hansard; the right-hand column contains a description of it, and further explanation if necessary. At the end is an index. Precedent Manual: Index 16 July 2004 IND 3 INDEX Absence of Minister see Minister not present Amendment/s to motion Abstention/s ..........................................................VOT3-4 Address in reply ....................................................OP12 Acting Minister answers question.........................