Revista História

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Celia M. Campbell CV 19/20

Celia M. Campbell Department of Classics [email protected] Emory University 221 E Candler Library Atlanta, GA 30322 EDUCATION DPhil in Latin Language & Literature November 2014 Trinity College, University of Oxford (UK) Supervisor: Professor Matthew Leigh “A Space for Song: Ovid’s Metapoetic Landscapes” MSt in Greek and/or Latin Language and Literature July 2010 Trinity College, University of Oxford (UK) Distinction “The Metamorphoses and Cyclic Epic: Ovid’s Renewal of an Epic Ideology” BA Classics, cum laude June 2009 Williams College (Massachusetts, USA) RESEARCH AND TEACHING INTERESTS Latin poetry of the late Republic and early Empire; Latin pseudepigrapha; post-Virgilian pastoral (especially Dante’s Latin eclogues); landscape and ecphrasis in Classical Literature; Senecan drama PROFESSIONAL APPOINTMENTS/ EMPLOYMENT Emory University August 2020 Assistant Professor of Classics Florida State University August 2018-May 2020 Dean’s Post-Doctoral Scholar University of Virginia August 2017-July 2018 Assistant Professor, General Faculty Fordham University August 2016- June 2017 Adjunct Instructor New York University January 2016- June 2017 Adjunct Instructor St. Anne’s College, University of Oxford September 2015-January 2016 Lecturer St. Anne’s College, University of Oxford October 2014- July 2015 Interim Head of Classics St. Anne’s College, University of Oxford October 2013- June 2014 Career Development Fellow Trinity College, University of Oxford October 2011- October 2013 Graduate Tutor St. Anne’s College, University of Oxford October -

THE MYTH of ORPHEUS and EURYDICE in WESTERN LITERATURE by MARK OWEN LEE, C.S.B. B.A., University of Toronto, 1953 M.A., Universi

THE MYTH OF ORPHEUS AND EURYDICE IN WESTERN LITERATURE by MARK OWEN LEE, C.S.B. B.A., University of Toronto, 1953 M.A., University of Toronto, 1957 A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OP PHILOSOPHY in the Department of- Classics We accept this thesis as conforming to the required standard THE UNIVERSITY OF BRITISH COLUMBIA September, i960 In presenting this thesis in partial fulfilment of the requirements for an advanced degree at the University of British Columbia, I agree that the Library shall make it freely available for reference and study. I further agree that permission for extensive copying of this thesis for scholarly purposes may be granted by the Head of my Department or by his representatives. It is understood that copying or publication of this thesis for financial gain shall not be allowed without my written permission. Department of The University of British Columbia Vancouver 8, Canada. ©he Pttttrerstt^ of ^riitsl} (Eolimtbta FACULTY OF GRADUATE STUDIES PROGRAMME OF THE FINAL ORAL EXAMINATION FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY of MARK OWEN LEE, C.S.B. B.A. University of Toronto, 1953 M.A. University of Toronto, 1957 S.T.B. University of Toronto, 1957 WEDNESDAY, SEPTEMBER 21, 1960 AT 3:00 P.M. IN ROOM 256, BUCHANAN BUILDING COMMITTEE IN CHARGE DEAN G. M. SHRUM, Chairman M. F. MCGREGOR G. B. RIDDEHOUGH W. L. GRANT P. C. F. GUTHRIE C. W. J. ELIOT B. SAVERY G. W. MARQUIS A. E. BIRNEY External Examiner: T. G. ROSENMEYER University of Washington THE MYTH OF ORPHEUS AND EURYDICE IN WESTERN Myth sometimes evolves art-forms in which to express itself: LITERATURE Politian's Orfeo, a secular subject, which used music to tell its story, is seen to be the forerunner of the opera (Chapter IV); later, the ABSTRACT myth of Orpheus and Eurydice evolved the opera, in the works of the Florentine Camerata and Monteverdi, and served as the pattern This dissertion traces the course of the myth of Orpheus and for its reform, in Gluck (Chapter V). -

Lucan's Natural Questions: Landscape and Geography in the Bellum Civile Laura Zientek a Dissertation Submitted in Partial Fulf

Lucan’s Natural Questions: Landscape and Geography in the Bellum Civile Laura Zientek A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of Washington 2014 Reading Committee: Catherine Connors, Chair Alain Gowing Stephen Hinds Program Authorized to Offer Degree: Classics © Copyright 2014 Laura Zientek University of Washington Abstract Lucan’s Natural Questions: Landscape and Geography in the Bellum Civile Laura Zientek Chair of the Supervisory Committee: Professor Catherine Connors Department of Classics This dissertation is an analysis of the role of landscape and the natural world in Lucan’s Bellum Civile. I investigate digressions and excurses on mountains, rivers, and certain myths associated aetiologically with the land, and demonstrate how Stoic physics and cosmology – in particular the concepts of cosmic (dis)order, collapse, and conflagration – play a role in the way Lucan writes about the landscape in the context of a civil war poem. Building on previous analyses of the Bellum Civile that provide background on its literary context (Ahl, 1976), on Lucan’s poetic technique (Masters, 1992), and on landscape in Roman literature (Spencer, 2010), I approach Lucan’s depiction of the natural world by focusing on the mutual effect of humanity and landscape on each other. Thus, hardships posed by the land against characters like Caesar and Cato, gloomy and threatening atmospheres, and dangerous or unusual weather phenomena all have places in my study. I also explore how Lucan’s landscapes engage with the tropes of the locus amoenus or horridus (Schiesaro, 2006) and elements of the sublime (Day, 2013). -

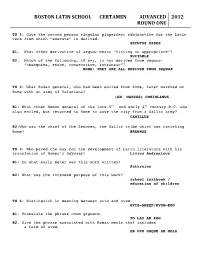

2012& ROUND&ONE&&! ! TU 1: Give the Second Person Singular Pluperfect Subjunctive for the Latin Verb from Which “Execute” Is Derived

BOSTON&LATIN&SCHOOL&&&&&&&CERTAMEN&&&&&&&&&&&ADVANCED&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&2012& ROUND&ONE&&! ! TU 1: Give the second person singular pluperfect subjunctive for the Latin verb from which “execute” is derived. SECUTUS ESSES B1. What other derivative of sequor means “fitting or appropriate”? SUITABLE B2. Which of the following, if any, is not derived from sequor: “obsequies, ensue, consecutive, intrinsic”? NONE: THEY ARE ALL DERIVED FROM SEQUOR TU 2: What Roman general, who had been exiled from Rome, later marched on Rome with an army of Volscians? (GN. MARCUS) CORIOLANUS B1: What other Roman general of the late 5th and early 4th century B.C. was also exiled, but returned to Rome to save the city from a Gallic army? CAMILLUS B2:Who was the chief of the Senones, the Gallic tribe which was ravishing Rome? BRENNUS TU 3: Who paved the way for the development of Latin literature with his translation of Homer’s Odyssey? Livius Andronicus B1: In what early meter was this work written? Saturnian B2: What was the intended purpose of this work? school textbook / education of children TU 4: Distinguish in meaning between ovis and ovum. OVIS—SHEEP/OVUM—EGG B1. Translate the phrase ovum gignere. TO LAY AN EGG B2. Give the phrase associated with Roman meals that includes a form of ovum. AB OVO USQUE AD MALA BOSTON&LATIN&SCHOOL&&&&&&&CERTAMEN&&&&&&&&&&&ADVANCED&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&2012&& ROUND&ONE,&page&2&&&! TU 5: Who am I? The Romans referred to me as Catamitus. My father was given a pair of fine mares in exchange for me. According to tradition, it was my abduction that was one the foremost causes of Juno’s hatred of the Trojans? Ganymede B1: In what form did Zeus abduct Ganymede? eagle/whirlwind B2: Hera was angered because the Trojan prince replaced her daughter as cupbearer to the gods. -

Scribes and Scholars (3Rd Ed. 1991)

SCRIBES AND SCHOLARS A Guide to the Transmission of Greek and Latin Literature BY L. D. REYNOLDS Fellow and Tutor of Brasenose College, Oxford AND N. G. WILSON Fellow and Tutor of Lincoln College, Oxford THIRD EDITION CLARENDON PRESS • OXFORD Oxford University Press, Walton Street, Oxford 0x2 6DP Oxford New York Athens Auckland Bangkok Bombay Calcutta Cape Town Dares Salaam Delhi Florence Hong Kong Istanbul Karachi Kuala Lumpur Madras Madrid Melbourne Mexico City Nairobi Paris Singapore Taipei Tokyo Toronto and associated companies in Berlin Ibadan Oxford is a trade mark of Oxford University Press Published in the United States by Oxford University Press Inc., New York © Oxford University Press 1968, 1974, 1991 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without the prior permission in writing of Oxford University Press. Within the UK, exceptions are allowed in respect of any fair dealing for the purpose of research or private study, or criticism or review, as permitted under the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act, 1988, or in the case of reprographic reproduction in accordance with the terms of the licences issued by the Copyright Licensing Agency. Enquiries concerning reproduction outside these terms and in other countries should be sent to the Rights Department, Oxford University Press, at the address above This book is sold subject to the condition that it shall not, by way of trade or otherwise, be lent, re-sold, hired out or otherwise circulated without the publisher s prior consent in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition including this condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data Data available Library of Congress Cataloging in Publication Data Scribes and scholars: a guide to the transmission of Greek and Latin literature/by L. -

Calendar of Roman Events

Introduction Steve Worboys and I began this calendar in 1980 or 1981 when we discovered that the exact dates of many events survive from Roman antiquity, the most famous being the ides of March murder of Caesar. Flipping through a few books on Roman history revealed a handful of dates, and we believed that to fill every day of the year would certainly be impossible. From 1981 until 1989 I kept the calendar, adding dates as I ran across them. In 1989 I typed the list into the computer and we began again to plunder books and journals for dates, this time recording sources. Since then I have worked and reworked the Calendar, revising old entries and adding many, many more. The Roman Calendar The calendar was reformed twice, once by Caesar in 46 BC and later by Augustus in 8 BC. Each of these reforms is described in A. K. Michels’ book The Calendar of the Roman Republic. In an ordinary pre-Julian year, the number of days in each month was as follows: 29 January 31 May 29 September 28 February 29 June 31 October 31 March 31 Quintilis (July) 29 November 29 April 29 Sextilis (August) 29 December. The Romans did not number the days of the months consecutively. They reckoned backwards from three fixed points: The kalends, the nones, and the ides. The kalends is the first day of the month. For months with 31 days the nones fall on the 7th and the ides the 15th. For other months the nones fall on the 5th and the ides on the 13th. -

Latin Literature

Latin Literature By J. W. Mackail Latin Literature I. THE REPUBLIC. I. ORIGINS OF LATIN LITERATURE: EARLY EPIC AND TRAGEDY. To the Romans themselves, as they looked back two hundred years later, the beginnings of a real literature seemed definitely fixed in the generation which passed between the first and second Punic Wars. The peace of B.C. 241 closed an epoch throughout which the Roman Republic had been fighting for an assured place in the group of powers which controlled the Mediterranean world. This was now gained; and the pressure of Carthage once removed, Rome was left free to follow the natural expansion of her colonies and her commerce. Wealth and peace are comparative terms; it was in such wealth and peace as the cessation of the long and exhausting war with Carthage brought, that a leisured class began to form itself at Rome, which not only could take a certain interest in Greek literature, but felt in an indistinct way that it was their duty, as representing one of the great civilised powers, to have a substantial national culture of their own. That this new Latin literature must be based on that of Greece, went without saying; it was almost equally inevitable that its earliest forms should be in the shape of translations from that body of Greek poetry, epic and dramatic, which had for long established itself through all the Greek- speaking world as a common basis of culture. Latin literature, though artificial in a fuller sense than that of some other nations, did not escape the general law of all literatures, that they must begin by verse before they can go on to prose. -

Teaching Through Images: Imagery in Greek and Roman Didactic Poetry” July 1-3, 2016

“Teaching through Images: Imagery in Greek and Roman Didactic Poetry” July 1-3, 2016 Seminar für Klassische Philologie Am Marstallhof 2-4 Hörsaal 513 Universität Heidelberg 69117 Heidelberg Organisers: Jenny Strauss Clay (Virginia), Athanassios Vergados (Heidelberg) If you are interested in attending, please contact Athanassios Vergados ([email protected]). July 1, 2016 9:15-9:30 Opening Remarks 9:30-10:15 Jenny Strauss Clay (Virginia): Binding Bonds: Anti-cosmic Elements in Hesiod’s Theogony. 10:15-11:00 Ilaria Andolfi (La Sapienza-Rome): Designing a Cosmic Architecture: Craftsmanship in Empedocles’ Poetry. 11:00-11:15 Coffee 11:15-12:00 Olga Chernyakhovskaya (Bamberg): Why humans don't cast off old skin like snakes: Images of knowledge and immortality in Nicander’s Theriaca. 12:00-12:45 Arnold Bärtschi (Bochum): Thinking in Pictures: The Orbis Descriptio of Dionysius Periegetes and the Construction of Imaginary Landscapes. 12:45-14:30 Lunch 14:30-15:15 Christophe Cusset (Lyon): Image and Vision: Visible and Invisible in the Phaenomena of Aratus. 15:15- 16:00 Patrick Glauthier (University of Pennsylvania): Analogy, Explanation, and Digression: The Milky Way in Aratus and Manilius. 16:00-16:15 Coffee 16:15- 17:00 Christopher Welser (Colby College): Astral Imagery in Georgics 4.457-459. 17:15-18:00 Christian Haß (Heidelberg): Narrate, Describe—and Vivify. Ekphrasis and Enargeia in Vergil’s Georgics. July 2, 2016 9:30-10:15 Zoe Stamatopoulou (Washington University St. Louis): Monsters and the Unnatural Body in Didactic Poetry. 10:15-11:00 Joseph Farrell (University of Pennsylvania): Insinuating claritas in Lucretius. -

A Close Study of Pliny the Elder's Naturalis Historia

SUMMA ABSOLUTAQUE NATURAE RERUM CONTEMPLATIO: A CLOSE STUDY OF PLINY THE ELDER’S NATURALIS HISTORIA 37 by EMILY CLAIRE BROWN B.A., The University of British Columbia, 2010 A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS in THE FACULTY OF GRADUATE STUDIES (Classics) THE UNIVERSITY OF BRITISH COLUMBIA (Vancouver) December 2012 © Emily Claire Brown, 2012 ABSTRACT The focus of modern scholarship on Pliny the Elder’s Naturalis Historia tends towards two primary goals: the placement of the work and the author within the cultural context of late 1st century CE Rome and, secondly, the acknowledgement of the purposeful and designed nature of Pliny’s text. Following this trend, the purpose of this study is to approach Book 37, in which Pliny lists and categorizes the gems of the world, as a deliberately structure text that is informed by its cultural context. The methodology for this project involved careful readings of the book, with special attention paid to the patterns hidden under the surface of Pliny’s occasionally convoluted prose; particular interest was paid to structural patterns and linguistic choices that reveal hierarchies. Of particular concern were several areas that appealed to the most prominent areas of concern in the book: the structure and form of the book; the colour terminology by which Pliny himself categorizes the gems; the identification of gems as objects of mirabilia and luxuria; and the identification of gems as objects of magia and medicina. These topics are all iterations of the basic question of whether gems represent to Pliny positive growth on the part of the Roman Empire, or detrimental decline. -

2019 Stanford CERTAMEN ADVANCED LEVEL ROUND 1 TU

2019 Stanford CERTAMEN ADVANCED LEVEL ROUND 1 TU 1. Translate this sentence into English: Servābuntne nōs Rōmānī, sī Persae īrātī vēnerint? WILL THE ROMANS SAVE US IF THE ANGRY PERSIANS COME? B1: What kind of conditional is illustrated in that sentence? FUTURE MORE VIVID B2: Now translate this sentence into English: Haec nōn loquerēris nisi tam stultus essēs. YOU WOULD NOT SAY THESE THINGS IF YOU WERE NOT SO STUPID TU 2. What versatile author may be the originator of satire, but is more famous for writing fabulae praetextae, fabulae palliatae, and the Annales? (QUINTUS) ENNIUS B1: What silver age author remarked that Ennius had three hearts on account of his trilingualism? AULUS GELLIUS B2: Give one example either a fabula praetexta or a fabula palliata of Ennius. AMBRACIA, CAUPUNCULA, PANCRATIASTES TU 3. What modern slang word, deriving from the Latin word for “four,” is defined by the Urban Dictionary as “crew, posse, gang; an informal group of individuals with a common identity and a sense of solidarity”? SQUAD B1: What modern slang word, deriving from a Latin word meaning “bend”, means “subtly or not-so-subtly showing off your accomplishments or possessions”? FLEX B2: What modern slang word, deriving from a Latin word meaning “end” and defined by the Urban Dictionary as “a word that modern teens and preteens say even though they have absolutely no idea what it really means,” roughly means “getting around issues or problems in a slick or easy way”? FINESSE TU 4. Who elevated his son Diadumenianus to the rank of Caesar when he became emperor in 217 A.D.? MACRINUS B1: Where did Macrinus arrange for the assisination of Caracalla? CARRHAE/EDESSA B2: What was the name of the person who actually did the stabbing of Caracalla? JULIUS MARTIALIS TU 5. -

CHG Library Book List

CHG Library Book List (Belgium), M. r. d. a. e. d. h. (1967). Galerie de l'Asie antérieure et de l'Iran anciens [des] Musées royaux d'art et d'histoire, Bruxelles, Musées royaux d'art et dʹhistoire, Parc du Cinquantenaire, 1967. Galerie de l'Asie antérieure et de l'Iran anciens [des] Musées royaux d'art et d'histoire by Musées royaux d'art et d'histoire (Belgium) (1967) (Director), T. P. F. H. (1968). The Metropolitan Museum of Art Bulletin: Volume XXVI, Number 5. New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art (January, 1968). The Metropolitan Museum of Art Bulletin: Volume XXVI, Number 5 by Thomas P.F. Hoving (1968) (Director), T. P. F. H. (1973). The Metropolitan Museum of Art Bulletin: Volume XXXI, Number 3. New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art (Ed.), A. B. S. (2002). Persephone. U.S.A/ Cambridge, President and Fellows of Harvard College Puritan Press, Inc. (Ed.), A. D. (2005). From Byzantium to Modern Greece: Hellenic Art in Adversity, 1453-1830. /Benaki Museum. Athens, Alexander S. Onassis Public Benefit Foundation. (Ed.), B. B. R. (2000). Christian VIII: The National Museum: Antiquities, Coins, Medals. Copenhagen, The National Museum of Denmark. (Ed.), J. I. (1999). Interviews with Ali Pacha of Joanina; in the autumn of 1812; with some particulars of Epirus, and the Albanians of the present day (Peter Oluf Brondsted). Athens, The Danish Institute at Athens. (Ed.), K. D. (1988). Antalya Museum. İstanbul, T.C. Kültür ve Turizm Bakanlığı Döner Sermaye İşletmeleri Merkez Müdürlüğü/ Ankara. (ed.), M. N. B. (Ocak- Nisan 2010). "Arkeoloji ve sanat. (Journal of Archaeology and Art): Ölümünün 100.Yıldönümünde Osman Hamdi Bey ve Kazıları." Arkeoloji Ve Sanat 133. -

Publications (Professor Rhiannon Ash) 'A Stylish Exit: Marcus Terentius' Swan-Song (Tacitus, Annals 6.8), Curtius Rufus

Publications (Professor Rhiannon Ash) ‘A Stylish Exit: Marcus Terentius’ Swan-Song (Tacitus, Annals 6.8), Curtius Rufus, and Virgil’, Classical Quarterly 71 (2021). ‘Un-Parallel Lives? The Younger Quintus and Marcus Cicero in Cicero’s Letters’, Hermathena 202 (2021). ‘The Staging of Death: Tacitus’ Agrippina the Younger and the Dramatic Turn’, in A. Damtoft Poulsen and A. Jönsson, Usages of the Past in Roman Historiography (Brill 2021), 197-224. ‘Ciuilis rabies usque in exitium (Histories 3.80.2): Tacitus and the Evolving Trope of Republican Civil War during the Principate’, in C. Lange and F.J. Vervaet (eds), The Historiography of Late Republican Civil War (Brill 2019), 351-75. ‘Paradoxography and Marvels in Post-Domitianic Literature: “An Extraordinary Affair, Even in the Hearing!”’, in A. König and C. Whitton (eds.) Roman Literature under Nerva, Trajan and Hadrian: Literary Interactions, AD 96–138. (Cambridge University Press 2018). Tacitus Annals 15 (Cambridge University Press 2018) Cambridge Greek and Latin Classics commentary. ‘Rhetoric and Roman Historiography’, in M. MacDonald (ed.), The Oxford Handbook of Rhetorical Studies (Oxford University Press 2017), 195-204. ‘The Biter Bit? Sejanus and Tiberius in Tacitus’ Annals, Omnibus 74 (2017). ‘Tacitus and the Poets: In Nemora et Lucos ... Secedendum est (Dialogus 9.6)?’, in P. Mitsis and I. Ziogas (eds), Wordplay and Powerplay in Latin Poetry (De Gruyter 2016), 13-35. ‘Drip-Feed Invective: Pliny, Self-Fashioning, and the Regulus Letters’, in A. Marmodoro and J. Hill (eds), The Author's Voice in Classical Antiquity (Oxford University Press 2016), 207-32. ‘Never Say Die! Assassinating Emperors in Suetonius Lives of the Caesars’, in K.