Xerox University Microfilms

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Historical Jesus a Contemporary Roman Perspective

Historical Jesus A Contemporary Roman Perspective Jason Janich NewLife906.com 1. Thallus 55 A.D. Thallus was a Greek Historian around 55A.D. who wrote a three volume account of the Eastern Mediterranean area. Although his works have been lost, fragments of it exist in the citations of others. As quoted by Julius Africansus (160 A.D -240 A.D.) On the whole world there pressed a most fearful darkness; and the rocks were rent by an earthquake, and many places in Judea and other districts were thrown down. This darkness Thallus, in the third book of his History, calls as appears to me without a reason, an eclipse of the sun. (Donaldson, A. R. (1973). Julius Africanus, Exant Writings, XVIII in the Ante- Nicene Fathers, ed Vol. VI. Grand RApids: Eerdmans.) What can we establish from Thallus’ writing? - The Christian Gospel was known in the Mediterranean by the middle of the first century – this is around AD 52, probably prior to the writing of the gospels. - There was a widespread darkness in the land, implied to have taken place during Jesus’ crucifixion. - Unbelievers offered rationalistic explanations for certain Christian teachings. 1 | P a g e 2. Pliny the Younger (61 A.D. – 113 A.D.) Letters 10.96-97 Pliny was the Governor of Bithynia in Asia Minor and is a noted historian with at least 10 volumes. In one letter he writes to the Emperor Trajan seeking counsel as to how to treat Christians. In the case of those who were denounced to me as Christians, I have observed the following procedure: I interrogated these as to whether they were Christians; those who confessed I interrogated a second and a third time, threatening them with punishment; those who persisted I ordered executed. -

The Count of the Saxon Shore by Alfred John Church

The Project Gutenberg EBook of The Count of the Saxon Shore by Alfred John Church This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at http://www.gutenberg.org/license Title: The Count of the Saxon Shore Author: Alfred John Church Release Date: October 31, 2013 [Ebook 44083] Language: English ***START OF THE PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK THE COUNT OF THE SAXON SHORE*** ii The Count of the Saxon Shore THE BURNING OF THE VILLA. The COUNT of the SAXON SHORE or The Villa in VECTIS ATALE OF THE DEPARTURE OF THE ROMANS FROM BRITAIN BY THE REV. ALFRED J. CHURCH, M.A. Author of “Stories from Homer” WITH THE COLLABORATION OF RUTH PUTNAM iv The Count of the Saxon Shore Fifth Thousand London SEELEY, SERVICE & CO. LIMITED 38 GREAT RUSSELL STREET Entered at Stationers’ Hall By SEELEY & CO. COPYRIGHT BY G. P. PUTNAM’S SONS, 1887 (For the United States of America). PREFACE. “Count of the Saxon Shore” was a title bestowed by Maximian (colleague of Diocletian in the Empire from 286 to 305 A.D.) on the officer whose task it was to protect the coasts of Britain and Gaul from the attacks of the Saxon pirates. It appears to have existed down to the abandonment of Britain by the Romans. So little is known from history about the last years of the Roman occupation that the writer of fiction has almost a free hand. -

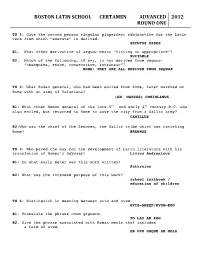

2012& ROUND&ONE&&! ! TU 1: Give the Second Person Singular Pluperfect Subjunctive for the Latin Verb from Which “Execute” Is Derived

BOSTON&LATIN&SCHOOL&&&&&&&CERTAMEN&&&&&&&&&&&ADVANCED&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&2012& ROUND&ONE&&! ! TU 1: Give the second person singular pluperfect subjunctive for the Latin verb from which “execute” is derived. SECUTUS ESSES B1. What other derivative of sequor means “fitting or appropriate”? SUITABLE B2. Which of the following, if any, is not derived from sequor: “obsequies, ensue, consecutive, intrinsic”? NONE: THEY ARE ALL DERIVED FROM SEQUOR TU 2: What Roman general, who had been exiled from Rome, later marched on Rome with an army of Volscians? (GN. MARCUS) CORIOLANUS B1: What other Roman general of the late 5th and early 4th century B.C. was also exiled, but returned to Rome to save the city from a Gallic army? CAMILLUS B2:Who was the chief of the Senones, the Gallic tribe which was ravishing Rome? BRENNUS TU 3: Who paved the way for the development of Latin literature with his translation of Homer’s Odyssey? Livius Andronicus B1: In what early meter was this work written? Saturnian B2: What was the intended purpose of this work? school textbook / education of children TU 4: Distinguish in meaning between ovis and ovum. OVIS—SHEEP/OVUM—EGG B1. Translate the phrase ovum gignere. TO LAY AN EGG B2. Give the phrase associated with Roman meals that includes a form of ovum. AB OVO USQUE AD MALA BOSTON&LATIN&SCHOOL&&&&&&&CERTAMEN&&&&&&&&&&&ADVANCED&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&2012&& ROUND&ONE,&page&2&&&! TU 5: Who am I? The Romans referred to me as Catamitus. My father was given a pair of fine mares in exchange for me. According to tradition, it was my abduction that was one the foremost causes of Juno’s hatred of the Trojans? Ganymede B1: In what form did Zeus abduct Ganymede? eagle/whirlwind B2: Hera was angered because the Trojan prince replaced her daughter as cupbearer to the gods. -

Internet Resource Booklet, 3Rd Edition

2 A Publication of the Robert C. Cooley Center for the Study of Early Christianity Gordon-Conwell Theological Seminary, Charlotte, North Carolina ©April, 2013 Cover picture by James R. Grams, www.game103.net Printed by PerfectImage! 3 Preface The websites offered here are of use not only to theological students and scholars but also to anyone interested in the topics. We hope that you find them as useful as we have for our interest in Biblical and Early Church studies, as well as related fields. While we have explored these sites ourselves, some comments are in order about the care needed in using websites in research. The researcher should be very careful on the web: it is sometimes similar to picking up information on a city street or in a shopping mall. How can we be sure that this information is worth citing? One way to be careful on the web is to look for institutional association or proof of academic authority. When using a website, investigate whether it is associated with a college or university, a research society, study center or institute, a library, publishing company, scholarly journal, and so forth. One might also see if the site manager or author is an academic engaged in ongoing research in the field. These sites are probably well worth using, just as any peer reviewed publication. Even so, the information may be more ‘work in progress’ than published data. Sites that reproduce printed matter can be useful in the same way if the works were published by reputable scholars and publishing companies—check for these (the researcher needs to cite this information along with the website in any case). -

Early Greek Alchemy, Patronage and Innovation in Late Antiquity CALIFORNIA CLASSICAL STUDIES

Early Greek Alchemy, Patronage and Innovation in Late Antiquity CALIFORNIA CLASSICAL STUDIES NUMBER 7 Editorial Board Chair: Donald Mastronarde Editorial Board: Alessandro Barchiesi, Todd Hickey, Emily Mackil, Richard Martin, Robert Morstein-Marx, J. Theodore Peña, Kim Shelton California Classical Studies publishes peer-reviewed long-form scholarship with online open access and print-on-demand availability. The primary aim of the series is to disseminate basic research (editing and analysis of primary materials both textual and physical), data-heavy re- search, and highly specialized research of the kind that is either hard to place with the leading publishers in Classics or extremely expensive for libraries and individuals when produced by a leading academic publisher. In addition to promoting archaeological publications, papyrolog- ical and epigraphic studies, technical textual studies, and the like, the series will also produce selected titles of a more general profile. The startup phase of this project (2013–2017) was supported by a grant from the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation. Also in the series: Number 1: Leslie Kurke, The Traffic in Praise: Pindar and the Poetics of Social Economy, 2013 Number 2: Edward Courtney, A Commentary on the Satires of Juvenal, 2013 Number 3: Mark Griffith, Greek Satyr Play: Five Studies, 2015 Number 4: Mirjam Kotwick, Alexander of Aphrodisias and the Text of Aristotle’s Meta- physics, 2016 Number 5: Joey Williams, The Archaeology of Roman Surveillance in the Central Alentejo, Portugal, 2017 Number 6: Donald J. Mastronarde, Preliminary Studies on the Scholia to Euripides, 2017 Early Greek Alchemy, Patronage and Innovation in Late Antiquity Olivier Dufault CALIFORNIA CLASSICAL STUDIES Berkeley, California © 2019 by Olivier Dufault. -

2019 Stanford CERTAMEN ADVANCED LEVEL ROUND 1 TU

2019 Stanford CERTAMEN ADVANCED LEVEL ROUND 1 TU 1. Translate this sentence into English: Servābuntne nōs Rōmānī, sī Persae īrātī vēnerint? WILL THE ROMANS SAVE US IF THE ANGRY PERSIANS COME? B1: What kind of conditional is illustrated in that sentence? FUTURE MORE VIVID B2: Now translate this sentence into English: Haec nōn loquerēris nisi tam stultus essēs. YOU WOULD NOT SAY THESE THINGS IF YOU WERE NOT SO STUPID TU 2. What versatile author may be the originator of satire, but is more famous for writing fabulae praetextae, fabulae palliatae, and the Annales? (QUINTUS) ENNIUS B1: What silver age author remarked that Ennius had three hearts on account of his trilingualism? AULUS GELLIUS B2: Give one example either a fabula praetexta or a fabula palliata of Ennius. AMBRACIA, CAUPUNCULA, PANCRATIASTES TU 3. What modern slang word, deriving from the Latin word for “four,” is defined by the Urban Dictionary as “crew, posse, gang; an informal group of individuals with a common identity and a sense of solidarity”? SQUAD B1: What modern slang word, deriving from a Latin word meaning “bend”, means “subtly or not-so-subtly showing off your accomplishments or possessions”? FLEX B2: What modern slang word, deriving from a Latin word meaning “end” and defined by the Urban Dictionary as “a word that modern teens and preteens say even though they have absolutely no idea what it really means,” roughly means “getting around issues or problems in a slick or easy way”? FINESSE TU 4. Who elevated his son Diadumenianus to the rank of Caesar when he became emperor in 217 A.D.? MACRINUS B1: Where did Macrinus arrange for the assisination of Caracalla? CARRHAE/EDESSA B2: What was the name of the person who actually did the stabbing of Caracalla? JULIUS MARTIALIS TU 5. -

Evidence for the Existence of Christianity and Jesus Christ In

for their crime. Or, the people of Samos for cult, and was crucified on that account. You burning Pythagoras? In one moment their country see, these misguided creatures start with the Evidence for the Existence was covered with sand. Or the Jews by murdering general conviction that they are immortal for all of Christianity and Jesus their wise king?. after that their kingdom was time, which explains their contempt for death and abolished. God rightly avenged these men. the self devotion . their lawgiver [taught] they are Christ in Secular History wise king. lived on in the teachings he enacted." all brothers, from the moment that they are converted, and deny the gods of Greece, and Roman Emperors: Phlegon was a historian who lived in the first worship the crucified sage, and live after his laws. century. There are two books credited to his name: All this they take on faith . " The Passing Hadrian, Imperator Caesar Trainus, (AD 76- Chronicles and the Olympiads. Little is known Peregrinus 138), was considered a man of culture and the arts. about Phlegon but he made reference to Christ. It appears he preferred peace rather than war. The The first two quotes are unique to Origen and the Thallus (circa A.D. 52) wrote a history about the following quote comes from a letter sent to last quote below is recorded by Origen and middle east from the time of the Trojan War to his Minucius Fundanus, proconsul of Asia, about how Philopon. own time. The work has been lost and the only to treat Christians. -

A COMPANION to the ROMAN ARMY Edited By

ACTA01 8/12/06 11:10 AM Page iii A COMPANION TO THE ROMAN ARMY Edited by Paul Erdkamp ACTA01 8/12/06 11:10 AM Page i A COMPANION TO THE ROMAN ARMY ACTA01 8/12/06 11:10 AM Page ii BLACKWELL COMPANIONS TO THE ANCIENT WORLD This series provides sophisticated and authoritative overviews of periods of ancient history, genres of classical lit- erature, and the most important themes in ancient culture. Each volume comprises between twenty-five and forty concise essays written by individual scholars within their area of specialization. The essays are written in a clear, provocative, and lively manner, designed for an international audience of scholars, students, and general readers. Ancient History Published A Companion to the Roman Army A Companion to the Classical Greek World Edited by Paul Erdkamp Edited by Konrad H. Kinzl A Companion to the Roman Republic A Companion to the Ancient Near East Edited by Nathan Rosenstein and Edited by Daniel C. Snell Robert Morstein-Marx A Companion to the Hellenistic World A Companion to the Roman Empire Edited by Andrew Erskine Edited by David S. Potter In preparation A Companion to Ancient History A Companion to Late Antiquity Edited by Andrew Erskine Edited by Philip Rousseau A Companion to Archaic Greece A Companion to Byzantium Edited by Kurt A. Raaflaub and Hans van Wees Edited by Elizabeth James A Companion to Julius Caesar Edited by Miriam Griffin Literature and Culture Published A Companion to Catullus A Companion to Greek Rhetoric Edited by Marilyn B. Skinner Edited by Ian Worthington A Companion to Greek Religion A Companion to Ancient Epic Edited by Daniel Ogden Edited by John Miles Foley A Companion to Classical Tradition A Companion to Greek Tragedy Edited by Craig W. -

The Church in Rome in the First Century

The Church in Rome in the First Century Author(s): Edmundson, George (1849-1930) Publisher: Grand Rapids, MI: Christian Classics Ethereal Library Description: In 1913, George Edmundson gave the University of Oxford©s Bampton Lectures, an annual (now biennial) lecture series that concentrates on Christian theological topics. This book contains the collection of Edmundson©s lectures, all of which concern Christianity©s first two hundred years. The majority of the book©s content addresses the New Testament directly, while a couple of the later lectures concern later early church figures such as Irenaeus, Clement of Alexandria, and Tertul- lian. During his time, Edmundson©s work was largely ignored, as he was a clergyman rather than a New Testament scholar. Not only this, but his conclusions differed vastly from the scholarly consensus of his contemporaries. Today, readers can approach Edmundson©s work as one piece of the ongoing dialogue in literary/historical criticism of the Bible. Kathleen O©Bannon CCEL Staff Subjects: Christianity History By period Early and medieval i Contents Title Page 1 Extract from the Last Will and Testament of the Late Rev. John Bampton 3 Synopsis of Contents 5 Lecture I 10 Lecture II 30 Lecture III 50 Lecture IV 71 Lecture V 90 Lecture VI 112 Lecture VII 136 Lecture VIII 154 Appendices 177 Note A. Chronological Table of Events Mentioned in the Lectures 178 Note B. Aquila and Prisca or Priscilla 181 Note C. The Pudens Legend 183 Note D. 188 Note E. The Tombs of the Apostles St. Peter and St. Paul 194 Note F. -

The Attic Nights of Aulus Gellius

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by ResearchArchive at Victoria University of Wellington Self-education and late-learners in The Attic Nights of Aulus Gellius By Joe Sheppard A Thesis Submitted to the Victoria University of Wellington in Fulfilment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts in Classics School of Art History, Classics and Religious Studies Victoria University of Wellington 2008 Self-education and Late-learners in The Attic Nights of Aulus Gellius This thesis was motivated by expressions of self-education during the early Roman Empire, an unusual topic that has never before been studied in detail. The elite cultural perspective nearly always ensured that Latin authors presented the topos of self-education as a case of social embarrassment or status dissonance that needed to be resolved, with these so-called autodidacts characterised as intellectual arrivistes . But the material remains written by self-educated men and women are expressed in more personal terms, complicating any simple definition and hinting at another side. The first half of this thesis builds a theory of self-education by outlining the social structures that contributed to the phenomenon and by investigating the means and the motivation likely for the successful and practical-minded autodidact. This framework is influenced by Pierre Bourdieu, whose work on culture, class, and education integrated similar concerns within a theory of habitus . As with other alternatives to the conventional upbringing of the educated classes, attempts at self-education were inevitable but ultimately futile. An autodidact by definition missed out on the manners, gestures, and morals that came with the formal education and daily inculcation supplied by the traditional Roman household. -

University Microfilms, a XEROX Company, Ann Arbor, Michigan

71- 27,433 BOBER, Richard John, 1931- THE LATINITAS OF SERVIUS. [Portions o f Text in L atin ], The Ohio State University, Ph.D., 1971 Language and Literature, classical University Microfilms, A XEROX Company, Ann Arbor, Michigan THIS DISSERTATION HAS BEEN MICROFILMED EXACTLY AS RECEIVED THE lATINITAS OF SERVIUS DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Richard John Bober, M.A. ***** The Ohio S ta te U n iv ersity 1971 Approved by Advise! Department of Classics vim September 17, 1931 > . Born - L o rain , Ohio 1949-1931................................ St, Charles College, Baltimore, Maryland I 95I-I 9 5 7...................... .... St. Mary Seminary, Cleveland, Ohio 1957-1959 ....................... Associate Pastor, Cleveland, Ohio 1959-I 96O ....................... M.A,, Catholic University of America, W ashington, D.C. 1960 -I963 .......................... Borromeo College Seminary, Vftckliffe, Ohio, Classics Department 1963-1965 ....... Graduate School, Ohio State University, Columbus, Ohio 1965-1975 .......................... Borromeo College Seminary, Wickliffe, Ohio, Department of Classics FIELDS OF STUDY fhjor Field: Greek and la tin literature Studies in Ancient History. Studies in Palaeography. Studies in Epigraphy. Studies in Archaeology. i i mBLE OF CONTENTS CHAPTER page VITA ........................................................................................... i i INTRODUCTTON............................................................................................................. -

Verrius Flaccus, His Alexandrian Model, Or Just an Anonymous Grammarian? the Most Ancient Direct Witness of a Latin Ars Grammatica*

The Classical Quarterly 70.2 806–821 © The Author(s), 2020. Published by Cambridge University Press on behalf of The Classical Association. This is an Open Access article, distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives licence (http://creative- commons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/), which permits non-commercial re-use, distribution, and repro- duction in any medium, provided the original work is unaltered and is properly cited. The written permission of Cambridge University Press must be obtained for commercial re-use or in order to cre- ate a derivative work. 806 doi:10.1017/S0009838820000749 VERRIUS FLACCUS, HIS ALEXANDRIAN MODEL, OR JUST AN ANONYMOUS GRAMMARIAN? THE MOST ANCIENT DIRECT WITNESS OF A LATIN ARS GRAMMATICA* When dealing with manuscripts transmitting otherwise unknown ancient texts and with- out a subscriptio, the work of a philologist and literary critic becomes both more diffi- cult and more engrossing. Definitive proof is impossible; at the end there can only be a hypothesis. When dealing with a unique grammatical text, such a hypothesis becomes even more delicate because of the standardization of ancient grammar. But it can happen that, behind crystallized theoretical argumentation and apparently canonical formulas, interstices can be explored that lead to unforeseen possibilities, more exciting—and even more suitable—than those that have already emerged. Since the publication of two papyrus fragments, both of which belong to the same ori- ginal roll, the grammatical text they transmit has attracted attention because of its unique- ness, and several famous grammarians have been named as possible auctores.1 This * The research leading to these results has received funding from the European Research Council (ERC) under the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation program (Grant agreement no.