A Quasi-Stationary Solution to Gliese 436B's Eccentricity

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Search for Another Earth – Part II

GENERAL ARTICLE The Search for Another Earth – Part II Sujan Sengupta In the first part, we discussed the various methods for the detection of planets outside the solar system known as the exoplanets. In this part, we will describe various kinds of exoplanets. The habitable planets discovered so far and the present status of our search for a habitable planet similar to the Earth will also be discussed. Sujan Sengupta is an 1. Introduction astrophysicist at Indian Institute of Astrophysics, Bengaluru. He works on the The first confirmed exoplanet around a solar type of star, 51 Pe- detection, characterisation 1 gasi b was discovered in 1995 using the radial velocity method. and habitability of extra-solar Subsequently, a large number of exoplanets were discovered by planets and extra-solar this method, and a few were discovered using transit and gravi- moons. tational lensing methods. Ground-based telescopes were used for these discoveries and the search region was confined to about 300 light-years from the Earth. On December 27, 2006, the European Space Agency launched 1The movement of the star a space telescope called CoRoT (Convection, Rotation and plan- towards the observer due to etary Transits) and on March 6, 2009, NASA launched another the gravitational effect of the space telescope called Kepler2 to hunt for exoplanets. Conse- planet. See Sujan Sengupta, The Search for Another Earth, quently, the search extended to about 3000 light-years. Both Resonance, Vol.21, No.7, these telescopes used the transit method in order to detect exo- pp.641–652, 2016. planets. Although Kepler’s field of view was only 105 square de- grees along the Cygnus arm of the Milky Way Galaxy, it detected a whooping 2326 exoplanets out of a total 3493 discovered till 2Kepler Telescope has a pri- date. -

Giant Planets

Lyot Conference 5 June 2007 Properties of Exoplanets: from Giants toward Rocky Planets & Informing Coronagraphy Collaborators: Paul Butler, Debra Fischer, Steve Vogt Chris McCarthy, Jason Wright, John Johnson, Katie Peek Chris Tinney, Hugh Jones, Brad Carter Greg Laughlin, Doug Lin, Shigeru Ida, Jack Lissauer, Eugenio Rivera -Stellar Sample - 1330 Nearby FGKM Stars (~2000 stars total with Mayor et al. ) Star Selection Criteria: HipparcosH-R Cat. Diagram d < 100 pc . 1330 Target Stars •Vmag < 10 mag • No Close Binaries • Age > 2 Gyr Lum 1.3 Msun Target List: 0.3 M Published SUN 1 Michel Mayor & Didier Queloz First ExoPlanet 51 Peg Now Stephane Udry plays leadership role also. Doppler Monitering Begun: 1987 Uniform Doppler Precision: 1-3 m s-1 2000 FGKM M.S. Stars Three Telescopes 8 Years 7 Years 19 Years (3.5 AU) (3 AU) (6 AU) Keck Lick Anglo-Aus. Tel. 2 Precision: 1.5 m s-1 3 Years Planets or Brown Dwarfs in Unclosed, Long-Period Orbits: Targets for Coronagraphs 3 Sep ~ 0.3 “ Sep ~ 0.2 “ 4 Sep ~ 0.2” Examples of Jupiter-mass & Saturn mass Planets Detected by RV 5 Jupiter Mass Extrasolar Planets P = 5.3 yr e = 0.47 Jupiter Mass Extrasolar Planets P = 1.3 yr 6 Sub-Saturn Masses: 30 - 100 MEarth Msini = 32 MEarth Msini = 37 MEarth Msini = 57 MEarth Old Doppler Precision: 3 m/s Sub-Saturn Masses: Detectable for P < 2 Month Multiple - Planet Systems 7 HD 12661: Sun-like Star ) (meters/sec Velocity Time (years) 2 - Planet Model 2.5 M J Weak Interactions 1.9 MJ K0V, 1Gy, 16 pc HD 128311 2:1 Resonance Inner Outer Per (d) 458 918 Msini 2.3 3.1 ecc 0.23 0.22 ω 119 212 Pc / Pb = 2.004 Dynamical Resonance (Laughlin) 8 Msini = 1.4 MJ M Dwarfs have distant giant planets. -

EPSC2018-126, 2018 European Planetary Science Congress 2018 Eeuropeapn Planetarsy Science Ccongress C Author(S) 2018

EPSC Abstracts Vol. 12, EPSC2018-126, 2018 European Planetary Science Congress 2018 EEuropeaPn PlanetarSy Science CCongress c Author(s) 2018 Stellar wind interaction with the expanding atmosphere of Gliese 436b A.G. Berezutskiy (1), I.F. Shaikhislamov (1), M.L. Khodachenko (2,3) and I.B. Miroshnichenko (1,4) (1) Institute of Laser Physics, Siberian Brunch Russian Academy of Science, Novosibirsk, Russia; (2) Space Research Institute, Austrian Academy of Science, Graz, Austria; (3) Skobeltsyn Institute of Nuclear Physics, Moscow State University, Moscow, Russia (4) Novosibirsk State Technical University, Novosibirsk, Russia ([email protected]) Abstract the escaping planetary upper atmospheric material are also taken into account. We study an exosphere of a Neptune-size exoplanet Gliese 436b, orbiting the red dwarf at an extremely 3. Results close distance (0.028 au), taking into account its interaction with the stellar wind plasma flow. It was At the initial state of the simulations, the atmosphere shown that Gliese 436 b has a bowshock region of Gliese 436b is assumed to consist of the molecular between planetary and stellar wind which localized hydrogen and helium atoms at a ratio NHe / NH2 = 1/5 on the distance of ~33 Rp, where density of planetary with the temperature 750 K. We consider the case of -3 atoms slightly dominates over the protons. a weak stellar wind (SW) with nsw=100 cm , Tsw=1 МК, Vsw=70 km/s, which is much less intense than 1. Introduction the solar wind. Because of this fact, , we did not consider generation of Energetic Neutral Atoms The modelled planet Gliese 436b has a mass (ENAs). -

Estudio Numérico De La Dinámica De Planetas

UNIVERSIDAD PEDAGOGICA´ NACIONAL FACULTAD DE CIENCIA Y TECNOLOG´IA ESTUDIO NUMERICO´ DE LA DINAMICA´ DE PLANETAS EXTRASOLARES Tesis presentada por Eduardo Antonio Mafla Mejia dirigida por: Camilo Delgado Correal Nestor Mendez Hincapie para obtener el grado de Licenciado en F´ısica 2015 Departamento de F´ısica I Dedico este trabajo a mi mam´a, quien me apoyo en mi deseo de seguir el camino de la educaci´on. Sin su apoyo este deseo no lograr´ıa ser hoy una realidad. RESUMEN ANALÍTICO EN EDUCACIÓN - RAE 1. Información General Tipo de documento Trabajo de Grado Acceso al documento Universidad Pedagógica Nacional. Biblioteca Central ESTUDIO NUMÉRICO DE LA DINÁMICA DE PLANETAS Título del documento EXTRASOLARES Autor(es) Mafla Mejia, Eduardo Antonio Director Méndez Hincapié, Néstor; Delgado Correal, Camilo Publicación Bogotá. Universidad Pedagógica Nacional, 2015. 61 p. Unidad Patrocinante Universidad Pedagógica Nacional DINÁMICA DE EXOPLANETAS, LEY GRAVITACIONAL DE NEWTON, Palabras Claves ESTUDIO NUMÉRICO. 2. Descripción Trabajo de grado que se propone evidenciar si el modelo matemático clásico newtoniano, y en consecuencia las tres leyes de Kepler, se puede generalizar a cualquier sistema planetario, o solo es válido para determinados casos particulares. Para lograr esto de comparar numéricamente los efectos de las diferentes correcciones que puede adoptar la ley de gravitación de Newton para modelar la dinámica de planetas extrasolares aplicándolos en los sistemas extrasolares Gliese 876 d, Gliese 436 b y el sistema Mercurio – Sol. En los exoplanetas examinados se encontró, que en un buen grado de aproximación, la dinámica de los exoplanetas se logran describir con el modelo newtoniano, y en consecuencia, modelar su movimiento usando las leyes de Kepler. -

Dynamical Evolution of the Gliese 436 Planetary System Kozai Migration As a Potential Source for Gliese 436B’S Eccentricity

A&A 545, A88 (2012) Astronomy DOI: 10.1051/0004-6361/201219183 & c ESO 2012 Astrophysics Dynamical evolution of the Gliese 436 planetary system Kozai migration as a potential source for Gliese 436b’s eccentricity H. Beust1, X. Bonfils1, G. Montagnier2,X.Delfosse1, and T. Forveille1 1 UJF-Grenoble 1 / CNRS-INSU, Institut de Planétologie et d’Astrophysique de Grenoble (IPAG) UMR 5274, 38041 Grenoble, France e-mail: [email protected] 2 European Organization for Astronomical Research in the Southern Hemisphere (ESO), Casilla 19001, Santiago 19, Chile Received 7 March 2012 / Accepted 1 August 2012 ABSTRACT Context. The close-in planet orbiting GJ 436 presents a puzzling orbital eccentricity (e 0.14) considering its very short orbital period. Given the age of the system, this planet should have been tidally circularized a long time ago. Many attempts to explain this were proposed in recent years, either involving abnormally weak tides, or the perturbing action of a distant companion. Aims. In this paper, we address the latter issue based on Kozai migration. We propose that GJ 436b was formerly located further away from the star and that it underwent a migration induced by a massive, inclined perturber via Kozai mechanism. In this context, the perturbations by the companion trigger high-amplitude variations to GJ 436b that cause tides to act at periastron. Then the orbit tidally shrinks to reach its present day location. Methods. We numerically integrate the 3-body system including tides and general relativity correction. We use a modified symplectic integrator as well as a fully averaged integrator. -

Exoplanet Detection Techniques

Exoplanet Detection Techniques Debra A. Fischer1, Andrew W. Howard2, Greg P. Laughlin3, Bruce Macintosh4, Suvrath Mahadevan5;6, Johannes Sahlmann7, Jennifer C. Yee8 We are still in the early days of exoplanet discovery. Astronomers are beginning to model the atmospheres and interiors of exoplanets and have developed a deeper understanding of processes of planet formation and evolution. However, we have yet to map out the full complexity of multi-planet architectures or to detect Earth analogues around nearby stars. Reaching these ambitious goals will require further improvements in instru- mentation and new analysis tools. In this chapter, we provide an overview of five observational techniques that are currently employed in the detection of exoplanets: optical and IR Doppler measurements, transit pho- tometry, direct imaging, microlensing, and astrometry. We provide a basic description of how each of these techniques works and discuss forefront developments that will result in new discoveries. We also highlight the observational limitations and synergies of each method and their connections to future space missions. Subject headings: 1. Introduction tary; in practice, they are not generally applied to the same sample of stars, so our detection of exoplanet architectures Humans have long wondered whether other solar sys- has been piecemeal. The explored parameter space of ex- tems exist around the billions of stars in our galaxy. In the oplanet systems is a patchwork quilt that still has several past two decades, we have progressed from a sample of one missing squares. to a collection of hundreds of exoplanetary systems. Instead of an orderly solar nebula model, we now realize that chaos 2. -

GLIESE 687 B—A NEPTUNE-MASS PLANET ORBITING a NEARBY RED DWARF

The Astrophysical Journal, 789:114 (14pp), 2014 July 10 doi:10.1088/0004-637X/789/2/114 C 2014. The American Astronomical Society. All rights reserved. Printed in the U.S.A. THE LICK–CARNEGIE EXOPLANET SURVEY: GLIESE 687 b—A NEPTUNE-MASS PLANET ORBITING A NEARBY RED DWARF Jennifer Burt1, Steven S. Vogt1, R. Paul Butler2, Russell Hanson1, Stefano Meschiari3, Eugenio J. Rivera1, Gregory W. Henry4, and Gregory Laughlin1 1 UCO/Lick Observatory, Department of Astronomy and Astrophysics, University of California at Santa Cruz, Santa Cruz, CA 95064, USA 2 Department of Terrestrial Magnetism, Carnegie Institute of Washington, Washington, DC 20015, USA 3 McDonald Observatory, University of Texas at Austin, Austin, TX 78752, USA 4 Center of Excellence in Information Systems, Tennessee State University, Nashville, TN 37209, USA Received 2014 February 24; accepted 2014 May 8; published 2014 June 20 ABSTRACT Precision radial velocities from the Automated Planet Finder (APF) and Keck/HIRES reveal an M sin(i) = 18 ± 2 M⊕ planet orbiting the nearby M3V star GJ 687. This planet has an orbital period P = 38.14 days and a low orbital eccentricity. Our Stromgren¨ b and y photometry of the host star suggests a stellar rotation signature with a period of P = 60 days. The star is somewhat chromospherically active, with a spot filling factor estimated to be several percent. The rotationally induced 60 day signal, however, is well separated from the period of the radial velocity variations, instilling confidence in the interpretation of a Keplerian origin for the observed velocity variations. Although GJ 687 b produces relatively little specific interest in connection with its individual properties, a compelling case can be argued that it is worthy of remark as an eminently typical, yet at a distance of 4.52 pc, a very nearby representative of the galactic planetary census. -

How to Detect Exoplanets Exoplanets: an Exoplanet Or Extrasolar Planet Is a Planet Outside the Solar System

Exoplanets Matthew Sparks, Sobya Shaikh, Joseph Bayley, Nafiseh Essmaeilzadeh How to detect exoplanets Exoplanets: An exoplanet or extrasolar planet is a planet outside the Solar System. Transit Method: When a planet crosses in front of its star as viewed by an observer, the event is called a transit. Transits by terrestrial planets produce a small change in a star's brightness of about 1/10,000 (100 parts per million, ppm), lasting for 2 to 16 hours. This change must be absolutely periodic if it is caused by a planet. In addition, all transits produced by the same planet must be of the same change in brightness and last the same amount of time, thus providing a highly repeatable signal and robust detection method. Astrometry: Astrometry is the area of study that focuses on precise measurements of the positions and movements of stars and other celestial bodies, as well as explaining these movements. In this method, the gravitational pull of a planet causes a star to change its orbit over time. Careful analysis of the changes in a star's orbit can provide an indication that there exists a massive exoplanet in orbit around the star. The astrometry technique has benefits over other exoplanet search techniques because it can locate planets that orbit far out from the star Radial Velocity method: The radial velocity method to detect exoplanet is based on the detection of variations in the velocity of the central star, due to the changing direction of the gravitational pull from an (unseen) exoplanet as it orbits the star. -

20 13 a N N Ual R Ep O Rt

2012 Annual Report 2013 Annual 2013 Report HEADQUARTERS LOCATION: Kamuela, Hawaii, USA MANAGEMENT: California Association for Research in Astronomy PARTNER INSTITUTIONS: California Institute of Technology (CIT/Caltech) University of California (UC) National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA) OBSERVATORY DIRECTOR: Taft E. Armandroff DEPUTY DIRECTOR: Hilton A. Lewis Observatory Groundbreaking: 1985 First light Keck I telescope: 1992 First light Keck II telescope: 1996 Federal Identification Number: 95-3972799 mission To advance the frontiers of astronomy and share our discoveries, inspiring the imagination of all. vision Cover: A spectacular aerial view A world in which all humankind is inspired of this extraordinary wheelhouse and united by the pursuit of knowledge of the of discovery with the shadow of Mauna Kea in the far distance. infinite variety and richness of the Universe. FY2013 Fiscal Year begins October 1 489 Observing Astronomers 434 Keck Science Investigations 309 table of contents Refereed Articles Director’s Report . P4 Triumph of Science . P7 Cosmic Visionaries . P19 Innovation from Day One . P21 118 Full-time Employees Keck’s Powerful Astronomical Instruments . P26 Funding . P31 Inspiring Imagination . P36 Science Bibliography . p40 Celebrating 20 years of revolutionary science from the W. M. Keck Observatory, Keck Week was a unique astronomy event that included a two-day science meeting. Here representing the Institute for Astronomy, University of Hawaii, Director Guenther Hasinger introduces Taft Armandroff for his closing talk, Census of Discovery. from Keck Observatory are humbling. I am very proud of what the Keck Observatory staff and the broader astronomy community have accomplished. In March 2013, Keck Observatory marked its 20th anniversary with a week of celebratory events. -

Exoplanet Detection Techniques

Fischer D. A., Howard A. W., Laughlin G. P., Macintosh B., Mahadevan S., Sahlmann J., and Yee J. C. (2014) Exoplanet detection techniques. In Protostars and Planets VI (H. Beuther et al., eds.), pp. 715–737. Univ. of Arizona, Tucson, DOI: 10.2458/azu_uapress_9780816531240-ch031. Exoplanet Detection Techniques Debra A. Fischer Yale University Andrew W. Howard University of Hawai‘i at Manoa Greg P. Laughlin University of California at Santa Cruz Bruce Macintosh Stanford University Suvrath Mahadevan The Pennsylvania State University Johannes Sahlmann Université de Genève Jennifer C. Yee Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics We are still in the early days of exoplanet discovery. Astronomers are beginning to model the atmospheres and interiors of exoplanets and have developed a deeper understanding of processes of planet formation and evolution. However, we have yet to map out the full com- plexity of multi-planet architectures or to detect Earth analogs around nearby stars. Reaching these ambitious goals will require further improvements in instrumentation and new analysis tools. In this chapter, we provide an overview of five observational techniques that are currently employed in the detection of exoplanets: optical and infrared (IR) Doppler measurements, transit photometry, direct imaging, microlensing, and astrometry. We provide a basic description of how each of these techniques works and discuss forefront developments that will result in new discoveries. We also highlight the observational limitations and synergies of each method and their connections to future space missions. 1. INTRODUCTION novations have advanced the precision for each of these techniques; however, each of the methods have inherent Humans have long wondered whether other solar systems observational incompleteness. -

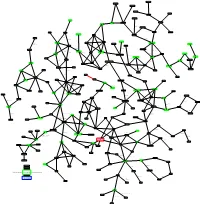

A Green Line Around the Box Means a Habitable Planet Exists in the Starsystem

Hussey 575 BD+30 2494 BD+24 2733 1.5 BD+14 2774 2.5 1.5 1.5 Ross 512 1.5 WO 9502 1.5 BD+17 2785 2 BD+15 3108 G136-101 Sigma Bootis BD+30 2512 1 Struve 1785 1.5 1 2.5 via LP441.33 1.5 BD+24 2786 1.5 1.5 1.5 1.5 1.5 45 Bootis L1344-37 GJ 3966 Ross 863 1.5 Lambda Serpentis Wolf 497 BD+25 2874 1.5 3 via V645 Herc Gliese 625 1 1.5 3.5 via GJ 3910 3 via V645 Herc 1.5 BD-9 3413 GJ-1179 Zeta Herculis 1.5 Eta Bootes 1 Rho Coronae Borealis 1.5 1.5 2.5 via Giclas 258.33 Luyten 758-105 BD+54 1716 1 BD+25 3173 Giclas 179-43 1.5 1.5 1.5 1 3 via Ross 948 3 via WO 9564 3 via GJ 3796 3 via Ross 948 Eta Coronae Borealis Chi Draconis 3 via HYG86887 1 3.5 via V645 Herc 1 Gamma Serpentis 2 BD+17 2611 (VESTA) Arcturus 3 via V645 Herc 3 via BD+21 2763 3.5 via BD+0 2989, DT Virginis 4 via HYG86887&8 Struve 2135 BD+33 2777 14 Herculis Porimma (Gamma Virginis) 3.5 via BD+45 2247 3 via BD+41 2695 1.5 3.5 BD+60 1623 BD+53 1719 THETIS 1.5 Chi Hercules 2 3.5 1.5 1.5 BD+38 3095 3.5 via BD+46 1189 Mu Herculis 4 via WO 9564 CR Draconis BD+52 2045 3 via BD+43 2796 1.5 3 via Giclas 179-43 BD+36 2393 Queen Isabel Star Sigma Draconis 3.5 via BD+43 2796 CE Bootes 1.5 BD+19 2881 1 1.5 1.5 1.5 2.5 I Bootis via BD+45 2247 BD+47 2112 1 4 via EGWD 329, CR Draconis 3 via LP 272-25 4.5 via Ross 948, L 910-10 44 Bootis Aitkens Double Star 1 ADS 10288 3 via BD+61 2068 1.5 Gilese 625 1.5 Vega 3 via Kuiper 79 3 via Giclas 179-43 4 via BD+46 1189, BD+50 2030 Ross 52 Theta Draconis 2 EV Lacertae Gliese 892 BD+39 2947 3 via BD+18 3421 1.5 0.5 Theta Bootis 1.5 3 via EV Lacertae 2.5 via -

AST413 Gezegen Sistemleri Ve Oluşumu Ders 1 : Tarihçe Ve Temel Yasalar Kozmogoni

AST413 Gezegen Sistemleri ve Oluşumu Ders 1 : Tarihçe ve Temel Yasalar Kozmogoni Milton'ın Evreni Evren nedir, nasıl bir yerdir ve biz nasıl oluştuk? → DinlerveFelsefe! Dinler ve Felsefe! Stonehenge M.Ö. 3000-2000 @ Wiltshire, İngiltere Kozmoloji Evren nasıl oluştu ve nasıl çalışıyor? → DinlerveFelsefe! Nedenselleştirme ve Bilim! Yer Merkezli Evren Modeli: Merkezinde hareketsiz Yer'in bulunduğu, hepsi Yer'e aynı uzaklıktaki yıldızların üstünde bulunduğu bir küre! 1. Yer'in küresel olduğu, 2. Yer'in büyüklüğü, 3. Tutulmalar bu modelle açıklanabilmiştir. Ancak, 1. Hızı diğer cisimlerden farklı olanlar? 2. Sabit hızla hareket etmeyenler? 3. Geri yönlü (retrograd) hareket yapanlar? “The School of Athens”, Raphael, 1509-1511 Dış Çemberlerle Retrograd Hareketi Açıklama Çabası Appolonius, dış çember kullanarak geri yönlü (retrograd) hareketi, Yer'i merkezden alıp, dış çemberin merkezinin hareketini diğer odağa göre sabit yaparak sabit hızla gerçekleşmeyen hareketi de başarıyla açıklamış oldu. Ama teorisi hala gezegen gözlemlerinde ulaşılan bazı gözlemsel sonuçları açıklayamıyordu. Batlamyus (Ptolemy) (90 – 168) bu problemi iki dış çember kullanarak gidermeye çalıştı. Perge'li Appolonius (MÖ 262 - 190) Güneş Merkezli Evren Modeli Böylece Mars ve Güneş'in konumlarını daha hassas ve çok daha basit bir modelle açıklamak mümkün oldu! Nicolas Copernicus (1473 - 1543) Tycho Brahé (1546 - 1601) Melez Yer-Güneş Merkezli Evren Modeli Tycho gelmiş geçmiş en iyi gözlemcilerden biri (belki de birincisi olduğu halde) Dünya'nın Güneş çevresinde dolanması durumunda yıldızların paralaktik hareket göstermesini beklediği halde bunu gözleyemediği için melez bir modele yöneldi. Eksik olan onun gözlemleri değil, paralaktik hareketi ölçecek teknolojiye (teleskop!) henüz ulaşılamamış olmasıydı... YÖRÜNGE DÖNEMİ – KAVUŞUM DÖNEMİ Kavuşum Dönemi (S): Gök cisminin aynı konfigürasyonda arka arkaya iki dizilişi arasındaki süre.