Lesbian Traces in Film

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Memory and Myth: the Bombings of Dresden and Hiroshima in German and Japanese TV Drama

Memory and myth: the bombings of Dresden and Hiroshima in German and Japanese TV drama GRISELDIS KIRSCH Abstract Japan is often blamed for not coming to terms with its own wartime past and for focusing solely on its role as a victim of the war. Germany, however, is often seen as the model that Japan has to emulate, having penitently accepted responsibility. Thus, in order to work out how these popular myths are being perpetuated, the media prove to be a good source of information, since they help to uphold memory and myth at the same time. In this paper, it will be examined how the “memory” of the bombings of Dresden and Hiroshima is being upheld in Japan and Germany2 and what kinds of “myths” are being created in the process. In focusing on two TV dramas, it shall be worked out to what extent Japan and Germany are represented as “victims” and to what extent, if at all, the issue of war responsibility features in these dramas. Keywords: Hiroshima; Dresden; war memory; television; television drama. 記憶と神話:ドイツと日本のテレビドラマにおけるドレスデン爆 撃と広島 グリゼルディス・キルシュ 日本は過去の戦争について清算せず、被害者意識ばかりに焦点を置い ている。それに対してドイツは反省して自らの戦争責任を受け入れて おり、日本は倣うべきであるとしばしば言われる。こうした 「神話」 がいかに受け継がれて来ているかを検証するにあたって、メディアは 重要な情報源であり、過去の記憶と同時に 「神話」を広め続けている。 本稿はドレスデン大空襲と広島の原爆の記憶が両国でどのように継承 Contemporary Japan 24 (2012), 51270 18692729/2012/02420051 DOI 10.1515/cj-2012-0003 © Walter de Gruyter Brought to you by | School of Oriental and African Studies (SOAS), University of London Authenticated Download Date | 1/20/20 3:33 PM 52 Griseldis Kirsch され、どのような「神話」 が築き上げられてきたかを二つのテレビド ラマに焦点をあてて見ていきたい。ドイツと日本が単に「犠牲者」 と して描かれているのか、そして、戦争責任についてどの程度触れられ ているかを検証する。 1. Introduction People bowing deeply in the Peace Park, in the background the Atomic Bomb Dome. -

Homer's Iliad Via the Movie Troy (2004)

23 November 2017 Homer’s Iliad via the Movie Troy (2004) PROFESSOR EDITH HALL One of the most successful movies of 2004 was Troy, directed by Wolfgang Petersen and starring Brad Pitt as Achilles. Troy made more than $497 million worldwide and was the 8th- highest-grossing film of 2004. The rolling credits proudly claim that the movie is inspired by the ancient Greek Homeric epic, the Iliad. This was, for classical scholars, an exciting claim. There have been blockbuster movies telling the story of Troy before, notably the 1956 glamorous blockbuster Helen of Troy starring Rossana Podestà, and a television two-episode miniseries which came out in 2003, directed by John Kent Harrison. But there has never been a feature film announcing such a close relationship to the Iliad, the greatest classical heroic action epic. The movie eagerly anticipated by those of us who teach Homer for a living because Petersen is a respected director. He has made some serious and important films. These range from Die Konsequenz (The Consequence), a radical story of homosexual love (1977), to In the Line of Fire (1993) and Air Force One (1997), political thrillers starring Clint Eastwood and Harrison Ford respectively. The Perfect Storm (2000) showed that cataclysmic natural disaster and special effects spectacle were also part of Petersen’s repertoire. His most celebrated film has probably been Das Boot (The Boat) of 1981, the story of the crew of a German U- boat during the Battle of the Atlantic in 1941. The finely judged and politically impartial portrayal of ordinary men, caught up in the terror and tedium of war, suggested that Petersen, if anyone, might be able to do some justice to the Homeric depiction of the Trojan War in the Iliad. -

Literature and Film of the Weimar Republic (In English Translation) OLLI@Berkeley, Spring 2019 Mondays, April 1—29, 2019 (5 Weeks), 10:00 A.M

Instructor: Marion Gerlind, PhD (510) 430-2673 • [email protected] Literature and Film of the Weimar Republic (in English translation) OLLI@Berkeley, Spring 2019 Mondays, April 1—29, 2019 (5 weeks), 10:00 a.m. — 12:30 p.m. University Hall 41B, Berkeley, CA 94720 In this interactive seminar we shall read and reflect on literature as well as watch and discuss films of the Weimar Republic (1919–33), one of the most creative periods in German history, following the traumatic Word War I and revolutionary times. Many of the critical issues and challenges during these short 14 years are still relevant today. The Weimar Republic was not only Germany’s first democracy, but also a center of cultural experimentation, producing cutting-edge art. We’ll explore some of the most popular works: Bertolt Brecht and Kurt Weill’s musical play, The Threepenny Opera, Joseph von Sternberg’s original film The Blue Angel, Irmgard Keun’s bestseller The Artificial Silk Girl, Leontine Sagan’s classic film Girls in Uniform, Erich Maria Remarque’s antiwar novel All Quiet on the Western Front, as well as compelling poetry by Else Lasker-Schüler, Gertrud Kolmar, and Mascha Kaléko. Format This course will be conducted in English (films with English subtitles). Your active participation and preparation is highly encouraged! I recommend that you read the literature in preparation for our sessions. I shall provide weekly study questions, introduce (con)texts in short lectures and facilitate our discussions. You will have the opportunity to discuss the literature/films in small and large groups. We’ll consider authors’ biographies in the socio-historical background of their work. -

The Cultural Memory of German Victimhood in Post-1990 Popular German Literature and Television

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Digital Commons@Wayne State University Wayne State University Wayne State University Dissertations 1-1-2010 The ulturC al Memory Of German Victimhood In Post-1990 Popular German Literature And Television Pauline Ebert Wayne State University Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.wayne.edu/oa_dissertations Part of the European History Commons, European Languages and Societies Commons, and the German Literature Commons Recommended Citation Ebert, Pauline, "The ulturC al Memory Of German Victimhood In Post-1990 Popular German Literature And Television" (2010). Wayne State University Dissertations. Paper 12. This Open Access Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by DigitalCommons@WayneState. It has been accepted for inclusion in Wayne State University Dissertations by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@WayneState. THE CULTURAL MEMORY OF GERMAN VICTIMHOOD IN POST-1990 POPULAR GERMAN LITERATURE AND TELEVISION by ANJA PAULINE EBERT DISSERTATION Submitted to the Graduate School of Wayne State University, Detroit, Michigan in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY 2010 MAJOR: MODERN LANGUAGES Approved by: ________________________________________ Advisor Date ________________________________________ ________________________________________ ________________________________________ ________________________________________ © COPYRIGHT BY ANJA PAULINE EBERT 2010 All Rights Reserved Dedication I dedicate this dissertation … to Axel for his support, patience and understanding; to my parents for their help in financial straits; to Tanja and Vera for listening; to my Omalin, Hilla Ebert, whom I love deeply. ii Acknowledgements In the first place I would like to express my deepest gratitude to my advisor, Professor Anne Rothe. -

German Films Quarterly 2 · 2004

German Films Quarterly 2 · 2004 AT CANNES In Competition DIE FETTEN JAHRE SIND VORBEI by Hans Weingartner FULFILLING EXPECTATIONS Interview with new FFA CEO Peter Dinges GERMAN FILM AWARD … and the nominees are … SPECIAL REPORT 50 Years Export-Union of German Cinema German Films and IN THE OFFICIAL PROGRAM OF THE In Competition In Competition (shorts) In Competition Out of Competition Die Fetten Der Tropical Salvador Jahre sind Schwimmer Malady Allende vorbei The Swimmer by Apichatpong by Patricio Guzman by Klaus Huettmann Weerasethakul The Edukators German co-producer: by Hans Weingartner Producer: German co-producer: CV Films/Berlin B & T Film/Berlin Thoke + Moebius Film/Berlin German producer: World Sales: y3/Berlin Celluloid Dreams/Paris World Sales: Celluloid Dreams/Paris Credits not contractual Co-Productions Cannes Film Festival Un Certain Regard Un Certain Regard Un Certain Regard Directors’ Fortnight Marseille Hotel Whisky Charlotte by Angela Schanelec by Jessica Hausner by Juan Pablo Rebella by Ulrike von Ribbeck & Pablo Stoll Producer: German co-producer: Producer: Schramm Film/Berlin Essential Film/Berlin German co-producer: Deutsche Film- & Fernseh- World Sales: Pandora Film/Cologne akademie (dffb)/Berlin The Coproduction Office/Paris World Sales: Bavaria Film International/ Geiselgasteig german films quarterly 2/2004 6 focus on 50 YEARS EXPORT-UNION OF GERMAN CINEMA 22 interview with Peter Dinges FULFILLING EXPECTATIONS directors’ portraits 24 THE VISIONARY A portrait of Achim von Borries 25 RISKING GREAT EMOTIONS A portrait of Vanessa Jopp 28 producers’ portrait FILMMAKING SHOULD BE FUN A portrait of Avista Film 30 actor’s portrait BORN TO ACT A portrait of Moritz Bleibtreu 32 news in production 38 BERGKRISTALL ROCK CRYSTAL Joseph Vilsmaier 38 DAS BLUT DER TEMPLER THE BLOOD OF THE TEMPLARS Florian Baxmeyer 39 BRUDERMORD FRATRICIDE Yilmaz Arslan 40 DIE DALTONS VS. -

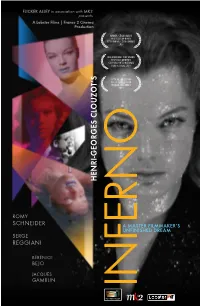

H En R I-G Eo R G Es C Lo U Z O

FLICKER ALLEY in association with MK2 presents A Lobster Films | France 2 Cinema Production WINNER, CÉSAR AWARD BEST DOCUMENTARY 35TH ANNUAL CÉSAR AWARDS 2010 INTERNATIONAL JURY AWARD BEST DOCUMENTARY SÃO PAULO INTERNATIONAL FILM FESTIVAL 2009 OFFICIAL SELECTION OUT OF COMPETITION T’S FESTIVAL DE CANNES 2009 OUZO HENRI-GEORGES CL ROMY SCHNEIDER A MASTER FILMMAKER’S UNFINISHED DREAM SERGE REGGIANI BÉRÉNICE BEJO JACQUES GAMBLIN FLICKER ALLEY in association with MK2 PRESENTS A LOBSTER FILMS | FRANCE 2 CINÉMA DISTRIBUTED BY: PRODUCTION FLICKER ALLEY PO Box 931762 Los Angeles, CA 90093 www.flickeralley.com PUBLICITY CONTACT: A SERGE BROMBERG AND RUXANDRA MEDREA FILM JEFF MASINO BASED ON AN ORIGINAL IDEA BY SERGE BROMBERG A FILM WRITTEN AND DIRECTED USING RUSHES FROM Office: (323) 878 0508 HENRI-GEORGES CLOUZOT’S INFERNO Fax: (323) 843 9367 ORIGINAL SCREENPLAY BY HENRI-GEORGES CLOUZOT, Email: [email protected] JOSÉ-ANDRÉ LACOUR AND JEAN FERRY RUNTIME: 94 MINUTES FRANCE, 2009, 35mm, HD, DIGIBETA, BETA SP, DVD FOR BOOKINGS PLEASE CONTACT: JESSICA ROSNER OPENS NEW YORK & LOS ANGELES Office: (212) 627 1785 JULY 2010 Mobile: (224) 545 3897 PHOTOS AND PRESS NOTES ARE AVAILABLE AT: [email protected] www.clouzotsinferno.com A LEGENDARY FILM In 1964, Henri-Georges Clouzot chose Romy Schneider, age 26, and Serge Reggiani, 42, to be the stars of INFERNO. It was an enigmatic and original project with an unlimited budget that was to be a cinematic “event” upon its release. But after three weeks of shooting, things took a turn for the worse. The project was stopped, and the images, which were said to be “incredible”, would remain unseen. -

+49(0)30.200 95 31- 1 [email protected]

FITZ+SKOGLUND AGENTS Linienstraße 218, 10119 Berlin Fon: +49(0)30.200 95 31-0 Fax: +49(0)30.200 95 31- 1 [email protected] www.fitz-skoglund.de FELICITAS WOLL 1980 Homberg height: 168 cm hair: dark blond eyes: green languages: english dialects: bavarian instruments: piano, guitar others: vocals driving license: car AWARDS 2017 Nominierung als beste Schauspielerin Deutscher Fernsehpreis für NACKT. DAS NETZ VERGISST NIE und DAS NEBELHAUS 2016 Publikumspreis des Deutschen Fernsehkrimi Festivals 2016 für DIE UNGEHORSAME Grimme Preis Nominierung für DIE UNGEHORSAME 2015 3Sat Zuschauerpreis für DIE UNGEHORSAME Bayerischer Fernsehpreis als Beste Hauptdarstellerin in DIE UNGEHORSAME Quotenmeter Fernsehpreis als als Beste Hauptdarstellerin in DIE UNGEHORSAME 2012 Ohrkanus als Beste Sprecherin in ANNA FREUD 2007 Diva Award für DRESDEN 2006 Nominierung Bambi als Beste Schauspielerin in DRESDEN Bayerischer Fernsehpreis für die Hauptrolle in DRESDEN 2004 The International Emmy Award für BERLIN BERLIN Deutscher Fernsehpreis für BERLIN BERLIN Goldene Rose von Luzern für die Hauptrolle in BERLIN BERLIN 2003 Adolf-Grimme-Preis für die Hauptrolle in BERLIN BERLIN 2002 Deutscher Fernsehpreis in der Kategorie Beste Schauspielerin – Serie 01 FITZ+SKOGLUND AGENTS Linienstraße 218, 10119 Berlin Fon: +49(0)30.200 95 31-0 Fax: +49(0)30.200 95 31-11 [email protected] www.fitz-skoglund.de FELICITAS WOLL CINEMA DIRECTOR 2018 BERLIN, BERLIN – DER KINOFILM Franziska Mayer Price 2014 HÖRDUR * FBW: Prädikat besonders wertvoll Ekrem Ergün 2012 EIN SCHMALER GRAT Daniel Harrich 2010 KEIN SEX IST AUCH KEINE LÖSUNG Torsten Wacker 2009 VATER MORGANA Till Endemann 2009 LIEBE MAUER Peter Timm 2003 ABGEFAHREN Jakob Schäuffelen 2001 MÄDCHEN MÄDCHEN Denis Gansel FILM+TV (SELECTION) DIRECTOR 2020 DU SOLLST NICHT LÜGEN / SAT.1 Jochen Freydank WEIHNACHTSTÖCHTER / ZDF Rolf Silber 2019 VÄTER ALLEIN ZU HAUS Jan Martin Scharf KRANKE GESCHÄFTE / ZDF Urs Egger 2018 VÄTER ALLEIN ZU HAUS Jan Martin Scharf 2017 TAUNUSKRIMI – IM WALD / ZDF Marcus O. -

Lesbians (On Screen) Were Not Meant to Survive

Lesbians (On Screen) Were not Meant to Survive Federica Fabbiani, Independent Scholar, Italy The European Conference on Media, Communication & Film 2017 Official Conference Proceedings Abstract My paper focuses on the evolution of the image of the lesbian on the screen. We all well know what can be the role of cinema in the structuring of the personal and collective imaginary and hence the importance of visual communication tools to share and spread lesbian stories "even" with a happy ending. If, in the first filmic productions, lesbians inevitably made a bad end, lately they are also able to live ‘happily ever after’. I do too believe that “cinema is the ultimate pervert art. It doesn't give you what you desire - it tells you how to desire” (Slavoy Žižek, 2006), that is to say that the lesbian spectator had for too long to operate a semantic reversal to overcome a performance deficit and to desire in the first instance only to be someone else, normal and normalized. And here it comes during the 2000s a commercial lesbian cinematography, addressed at a wider audience, which well interpret the actual trend, that most pleases the young audience (considering reliable likes and tweets on social networks) towards normality. It is still difficult to define precisely these trends: what would queer scholars say about this linear path toward a way of life that dares only to return to normality? No more eccentric, not abject, perhaps not even more lesbians, but 'only' women. Is this pseudo-normality (with fewer rights, protections, privileges) the new invisibility? Keywords: Lesbianism, Lesbian cinema, Queer cinema, LGBT, Lesbian iafor The International Academic Forum www.iafor.org Introduction I would try to trace how the representation of lesbians on screen has developed over time. -

Hliebing Dissertation Revised 05092012 3

Copyright by Hans-Martin Liebing 2012 The Dissertation Committee for Hans-Martin Liebing certifies that this is the approved version of the following dissertation: Transforming European Cinema : Transnational Filmmaking in the Era of Global Conglomerate Hollywood Committee: Thomas Schatz, Supervisor Hans-Bernhard Moeller Charles Ramírez Berg Joseph D. Straubhaar Howard Suber Transforming European Cinema : Transnational Filmmaking in the Era of Global Conglomerate Hollywood by Hans-Martin Liebing, M.A.; M.F.A. Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of The University of Texas at Austin in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy The University of Texas at Austin May 2012 Dedication In loving memory of Christa Liebing-Cornely and Martha and Robert Cornely Acknowledgements I would like to thank my committee members Tom Schatz, Charles Ramírez Berg, Joe Straubhaar, Bernd Moeller and Howard Suber for their generous support and inspiring insights during the dissertation writing process. Tom encouraged me to pursue this project and has supported it every step of the way. I can not thank him enough for making this journey exciting and memorable. Howard’s classes on Film Structure and Strategic Thinking at The University of California, Los Angeles, have shaped my perception of the entertainment industry, and having him on my committee has been a great privilege. Charles’ extensive knowledge about narrative strategies and Joe’s unparalleled global media expertise were invaluable for the writing of this dissertation. Bernd served as my guiding light in the complex European cinema arena and helped me keep perspective. I consider myself very fortunate for having such an accomplished and supportive group of individuals on my doctoral committee. -

Kih Presse 09

Der Ort Nach den außerordentlichen Erfolgen der vergangenen Jahre mit u.a. ”Der rote Korsar”, “Die Legende vom Ozeanpianisten” oder “Master and Commander” (am Abend genießen bis zu 5.000 Besucher die ausgefallene Kino-Atmosphäre) wird es am 07. und 08. August 2009 wieder ein fil- misches Open-Air-Spektakel im ”Schaufenster Fischereihafen” geben. Beginn ist jeweils ca. 22 Uhr (Einbruch der Dunkelheit) - immer mit Vorprogramm ab 21 Uhr. Veranstalter ist erneut das Kulturamt der Seestadt Bremerhaven. Der Eintritt ist frei. Kino im Hafen 2009 Der Ort Unterstützt wird das Vorhaben von einer Vielzahl namhafter, regional ansässiger Firmen. In bewährter Technik werden insgesamt 20 Container das Rückgrat für die Leinwand bilden, die mit rd.180 Quadratmetern Fläche die Maße einer ausgewachsenen 7-Zimmer-Wohnung erreicht. Aus Containern wird ebenfalls die Projektionskabine für den zentnerschweren Spezial- Filmprojektor gebaut, der das Bild gut 70 Meter weit auf die Leinwand werfen wird. Bereits seit 1996 genießen Touristen und Einheimische die ausgefallene Kino-Atmosphäre. Laut Verband der Filmverleiher gehört "Kino im Hafen" auf Grund der Besucherzahlen zu den Top Ten der Freiluftkinos in Deutschland. Kino im Hafen 2009 Die Filme AM 07.08.: Finnischer Tango Alex hat keine Freundin, keine netten Eltern und keinen Bausparvertrag. Dafür hat er den Finnischen Tango. Sein Akkordeon ist ihm wichtiger als seine Kumpels, mit denen er erfolglos durch Deutschland tourt – bis sich einer der bei- den das Leben nimmt und der andere Band und Freundschaft aufkündigt. Alex steht plötzlich allein da. Auf der Flucht vor Schulden und Einsamkeit erfährt er von einer Behindertentheatergruppe, die noch einen Mitspieler sucht. -

Troy from Homer's Iliad to Hollywood Epic

Troy From Homer’s Iliad to Hollywood Epic H Troy From Homer’s Iliad to Hollywood Epic Edited by Martin M. Winkler © 2007 by Blackwell Publishing Ltd blackwell publishing 350 Main Street, Malden, MA 02148-5020, USA 9600 Garsington Road, Oxford OX4 2DQ, UK 550 Swanston Street, Carlton, Victoria 3053, Australia The right of Martin M. Winkler to be identified as the Author of the Editorial Material in this Work has been asserted in accordance with the UK Copyright, Designs, and Patents Act 1988. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, except as permitted by the UK Copyright, Designs, and Patents Act 1988, without the prior permission of the publisher. First published 2007 by Blackwell Publishing Ltd 1 2007 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Troy : from Homer’s Iliad to Hollywood epic / edited by Martin M. Winkler. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN-13: 978-1-4051-3182-7 (hardcover : alk. paper) ISBN-10: 1-4051-3182-9 (hardcover : alk. paper) ISBN-13: 978-1-4051-3183-4 (pbk. : alk. paper) ISBN-10: 1-4051-3183-7 (pbk. : alk. paper) 1. Troy (Motion picture) 2. Trojan War. 3. Trojan War—Motion pictures and the war. I. Winkler, Martin M. PN1997.2.T78 2007 791.43′72—dc22 2005030974 A catalogue record for this title is available from the British Library. Set in 10/12.5pt Photina by Graphicraft Limited, Hong Kong Printed and bound in Singapore by Fabulous Printers The publisher’s policy is to use permanent paper from mills that operate a sustainable forestry policy, and which has been manufactured from pulp processed using acid-free and elementary chlorine-free practices. -

Different from the Others

DIFFERENT FROM THE OTHERS A Comparative Analysis of Representations of Male Queerness and Male-Male Intimacy in the Films of Europe and America, 1912-1934 A thesis submitted to the University of East Anglia for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy By Shane Brown School of Film, Television and Media ©This copy of the thesis has been supplied on condition that anyone who consults it is understood to recognise that its copyright rests with the author and that use of any information derived there from must be in accordance with current UK Copyright Law. In addition, any quotation or extract must include full attribution. 1 | P a g e ABSTRACT Since the publication of Vito Russo's now classic study, The Celluloid Closet, in 1981, much has been written on the representation of queer characters on screen. However, no full length work on the representation of queer sexualities in silent and early sound film has yet been published, although the articles and chapters of Dyer (1990), Kuzniar (2000) and Barrios (2003) are currently taken as the definitive accounts of these issues. However, each of the above studies deals with a specific country or region and, since their publication, a significant number of silent films have been discovered that were previously thought lost. There has also been a tendency in the past to map modern concepts of sexuality and gender on to films made nearly one hundred years ago. This thesis, therefore, compares the representations of male queerness and male-male intimacy in the films of America and Europe during the period 1912 to 1934, and does so by placing these films within the social and cultural context in which they were made.