The Early Generations of University Women in Fiction

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Literature and Film of the Weimar Republic (In English Translation) OLLI@Berkeley, Spring 2019 Mondays, April 1—29, 2019 (5 Weeks), 10:00 A.M

Instructor: Marion Gerlind, PhD (510) 430-2673 • [email protected] Literature and Film of the Weimar Republic (in English translation) OLLI@Berkeley, Spring 2019 Mondays, April 1—29, 2019 (5 weeks), 10:00 a.m. — 12:30 p.m. University Hall 41B, Berkeley, CA 94720 In this interactive seminar we shall read and reflect on literature as well as watch and discuss films of the Weimar Republic (1919–33), one of the most creative periods in German history, following the traumatic Word War I and revolutionary times. Many of the critical issues and challenges during these short 14 years are still relevant today. The Weimar Republic was not only Germany’s first democracy, but also a center of cultural experimentation, producing cutting-edge art. We’ll explore some of the most popular works: Bertolt Brecht and Kurt Weill’s musical play, The Threepenny Opera, Joseph von Sternberg’s original film The Blue Angel, Irmgard Keun’s bestseller The Artificial Silk Girl, Leontine Sagan’s classic film Girls in Uniform, Erich Maria Remarque’s antiwar novel All Quiet on the Western Front, as well as compelling poetry by Else Lasker-Schüler, Gertrud Kolmar, and Mascha Kaléko. Format This course will be conducted in English (films with English subtitles). Your active participation and preparation is highly encouraged! I recommend that you read the literature in preparation for our sessions. I shall provide weekly study questions, introduce (con)texts in short lectures and facilitate our discussions. You will have the opportunity to discuss the literature/films in small and large groups. We’ll consider authors’ biographies in the socio-historical background of their work. -

Lesbians (On Screen) Were Not Meant to Survive

Lesbians (On Screen) Were not Meant to Survive Federica Fabbiani, Independent Scholar, Italy The European Conference on Media, Communication & Film 2017 Official Conference Proceedings Abstract My paper focuses on the evolution of the image of the lesbian on the screen. We all well know what can be the role of cinema in the structuring of the personal and collective imaginary and hence the importance of visual communication tools to share and spread lesbian stories "even" with a happy ending. If, in the first filmic productions, lesbians inevitably made a bad end, lately they are also able to live ‘happily ever after’. I do too believe that “cinema is the ultimate pervert art. It doesn't give you what you desire - it tells you how to desire” (Slavoy Žižek, 2006), that is to say that the lesbian spectator had for too long to operate a semantic reversal to overcome a performance deficit and to desire in the first instance only to be someone else, normal and normalized. And here it comes during the 2000s a commercial lesbian cinematography, addressed at a wider audience, which well interpret the actual trend, that most pleases the young audience (considering reliable likes and tweets on social networks) towards normality. It is still difficult to define precisely these trends: what would queer scholars say about this linear path toward a way of life that dares only to return to normality? No more eccentric, not abject, perhaps not even more lesbians, but 'only' women. Is this pseudo-normality (with fewer rights, protections, privileges) the new invisibility? Keywords: Lesbianism, Lesbian cinema, Queer cinema, LGBT, Lesbian iafor The International Academic Forum www.iafor.org Introduction I would try to trace how the representation of lesbians on screen has developed over time. -

10 Wittman & Liebenberg Finalx

138 MÄDCHEN IN UNIFORM – GENDER, POWER AND SEXUALITY IN TIMES OF MILITARISATION Gerda-Elisabeth Wittmann North-West University, Potchefstroom Campus Ian Liebenberg Faculty of Military Science, Stellenbosch University Abstract The film Mädchen in Uniform (1931), a love story between a teacher and student in Germany, is widely recognised as the first pro-lesbian film. Banned by the National Socialists, it opened the way for pro-lesbian film production and was followed by films such as Acht Mädels im Boot (1932), Anna and Elisabeth (1933) and Ich für dich, du für mich (Me for You, You for Me, 1934). These films strongly contrasted with documentaries and popular films of the Third Reich that portrayed a new and heroic German nation growing from the ashes of defeat following the uneasy Peace of Versailles. The film Aimée & Jaguar (1999) revisited the theme of lesbian love during the National Socialist regime. Based on a true story, the film is a narrative of the love between a German and a Jewish woman. Despite controversy, the film won numerous prizes in Germany. This article investigates the portrayal of gender and power in Mädchen in Uniform and Aimée & Jaguar. It seeks to explain how lesbian women and the love between them were portrayed in a time of male domination, militarism and what was seen as hetero-normality. This contribution examines gender-related power struggles and the political climate in Germany at the time of the Weimar Republic and the build-up to National-Socialist militarism. Introduction This article deals with a case study of filmic art that illustrates the tensions between the somatic search for freedom and the constraints of a society that longed Scientia Militaria, South African for law, order, authority, and, if needs be, Journal of Military Studies, Vol military force. -

Muchachas-De-Uniforme.Pdf

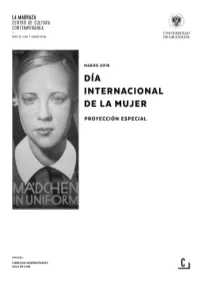

Sábado 9 marzo 20 h. DÍA INTERNACIONAL DE LA MUJER Sala Máxima del Espacio V Centenario Proyección Especial (Antigua Facultad de Medicina en Av. de Madrid) Entrada libre hasta completar aforo MUCHACHAS DE UNIFORME (1931) Alemania 83 min. Título Orig.- Mädchen in Uniform. Director.- Leontine Sagan & Carl Froelich. Argumento.- Las obras teatrales “Ritter Nérestan” (“Caballero Nérestan”, 1930) y “Gestern und Heuten” (“Ayer y hoy”, 1931) de Christa Winsloe. Guión.- Christa Winsloe y Friedrich Dammann. Fotografía.- Reimar Kuntze y Franz Weihmayr (1.20:1 – B/N). Montaje.- Oswald Hafenrichter. Música.- Hanson Milde-Meissner. Productor.- Carl Froelich y Friedrich Pflughaupt. Producción.- Deutsche Film- Gemeinschaft / Bild und Ton GmbH. Intérpretes.- Hertha Thiele (Manuela von Meinhardis), Dorothea Wieck (señorita von Bernburg), Hedwig Schlichter (señorita von Kesten), Ellen Schwanneke (Ilse von Westhagen), Emilia Unda (la directora), Erika Biebrach (Lilli von Kattner), Lene Berdoit (señorita von Gaerschner), Margory Bodker (señorita Evans), Erika Mann (señorita von Atems), Gertrud de Lalsky (tía de Manuela). Versión original en alemán con subtítulos en español Película nº 1 de la filmografía de Leontine Sagan (de 3 como directora) Premio del Público en el Festival de Venecia Música de sala: Berlin Cabaret songs Ute Lemper 3 En los primeros años de la historia cinematográfica alemana, la atracción entre mujeres en las películas mudas aparece sólo someramente, al margen y en la forma de Hosenrollen (muje- res con pantalones).1 En un momento de necesidad -

Rezension Über: Jennifer Drake Askey, Good Girls, Good Germans. Girls' Education

Zitierhinweis Jacobi, Juliane: Rezension über: Jennifer Drake Askey, Good Girls, Good Germans. Girls’ Education and Emotional Nationalism in Wilhelminian Germany, New York: Camden House, 2013, in: German Historical Institute London Bulletin, Vol. XXXVI (2014), 2, S. 69-74, DOI: 10.15463/rec.1189742239, heruntergeladen über recensio.net First published: http://www.ghil.ac.uk/index.php?eID=tx_nawsecuredl=0 copyright Dieser Beitrag kann vom Nutzer zu eigenen nicht-kommerziellen Zwecken heruntergeladen und/oder ausgedruckt werden. Darüber hinaus gehende Nutzungen sind ohne weitere Genehmigung der Rechteinhaber nur im Rahmen der gesetzlichen Schrankenbestimmungen (§§ 44a-63a UrhG) zulässig. JENNIFER DRAKE ASKEY , Good Girls, Good Germans: Girls’ Edu - cation and Emotional Nationalism in Wilhelminian Germany , Studies in German Literature, Linguistics, and Culture (New York: Camden House, 2013), x + 201 pp. ISBN 978 1 57113 562 9. £55.00 The national education of young people in Imperial Germany has been widely studied. The author of the book under review here adds a new aspect to the theme: the emotional education of the daughters of the upper middle class (she herself speaks of the ‘middle class’ throughout) by reading relevant, nationally oriented literature, both inside and outside school. Referring to studies by Silvia Bovenschen, 1 Ute Frevert, 2 and Ruth-Ellen Boetcher Joeres, 3 Askey reports that the impact of misogynistic nineteenth-century German-language litera - ture on women has been sufficiently investigated, while middle-class girls remain largely invisible. What it meant for these future women to be exposed to this misogynistic literature is the subject of the four chapters comprising this book. The book starts with an outline of the development of secondary schooling for girls after the foundation of Imperial Germany, provid - ing the institutional framework within which the daughters of Prussia’s wealthy classes were imbued with a basic patriarchal un - derstanding of the world. -

Space and Gender in Post-War German Film

The Misogyny of the Trümmerfilm - Space and Gender in Post-War German film A thesis submitted to the University of Reading For the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of Modern Languages and European Studies Richard M. McKenzie January 2017 1 | Page Acknowledgements I would like to express my thanks to my supervisors Dr Ute Wölfel and Prof. John Sandford for their support, guidance and supervision whilst my thesis was developing and being written. It has been a pleasure to discuss the complexities of the Trümmerfilm with you both over multiple coffees during the last few years. I am also grateful for the financial support provided by the Reading University Modern Foreign Languages Department at the beginning of my PhD study. My thanks must also go to Kathryn, Sophie and Isabelle McKenzie, with my parents and sister, for their forbearance whilst I concentrated on my thesis. In addition to my supervisors and family, I would like to record my thanks to my friends; Prof. Paul Francis, Dr Peter Lowman, Dr Daniela La Penna, Dr Simon Mortimer, Dr J.L. Moys and D.M. Pursglove for their vital encouragement at different points over the last few years. Finally, I would like to acknowledge the debt that I owe to two people. Firstly, Herr Wilfred Muscheid of the Frankfurt International School who introduced me to the intricacies of the German language ultimately making my PhD study possible. Secondly, I would like to acknowledge the influence of the late Prof. Lindsey Hughes, lecturer in the former Reading University Russian Department, who, with her departmental colleagues, taught me many of the basic academic tools and determination that I have needed to complete my PhD. -

Of Cinema Through European Film History ••••••••••• the Centenary of Cinema

the centenary Wo~;~~;r~th of cinema through European film history ••••••••••• the centenary of cinema ISBN : 92·827·6375·7 CC·AG·96·001·EN·C The TVomen of Europe Dossiers issue no. 43 ((The Centenary of Cinema: TVomen5 path through European film history" is available in the official lan guages of the European Union. The production of the dossier was overseen by Jackie BUET, director of the International TVomen 5 Film Festival in Creteil, France, in collaboration with: Elisabeth JENNY editor We wish to thank our contributors: Karin BRUNS and Silke HABIGER (Deutschland) Femme Totale Frauenfilmfestival Jean-Fran~ois CAMUS (France) Festival d'Annecy Rosilia COELHO (Portugal) IPACA (Instituto Portugues da arte cinematografica) Helen DE WITT (Great Britain) Cine Nova Maryline FELLOUS (France) Correspondentforformer USSR countries Renee GAGNON (Portugal) Uni-Portugal Gabriella GUZZI (Italia) Centro Problemi Donna Monique and Guy HENNEBELLE (France) Film critics Heike HURST (France) Professor of.film review Gianna MURA (France) Correspondent for Italy Paola PAOLI (Italia) Laboratorio Immagine Donna Daniel SAUVAGET (France) Film critic Ana SOLA (Espana) DRAG MAGic Moira SULLIVAN (Sverige) Correspondentfor Sweden and .film critic Dorothee ULRICH (France) Goethe Institut Ginette VINCENDEAU (Great Britain) Journalist and film teacher Director of publication/Editor-in-chief: Veronique Houdart-Biazy, Head of Section, Information for J;Vc,men, Directorate-General X- Information, Communication, Culture and Audiovisual Media Postal address: Rue de la Loi 200, B-1 049 Brussels Contact address: Rue de Treves 120, B-1 040 Brussels Tel (32 2) 299 91 24 - Fax (32 2) 299 38 91 Production: Temporary Association BLS-CREW-SPE, rue du Marteau 8, B-121 0 Brussels 0 Printed with vegetable-based ink on unbleached, recycled paper. -

Między Stłumieniem a Autentycznością. Metafora Don Carlosa W Filmie Leontine Sagan Dziewczęta W Mundurkach

Daria Mazur Między stłumieniem a autentycznością. Metafora Don Carlosa w filmie Leontine Sagan Dziewczęta w mundurkach ABSTRACT. Mazur Daria, Między stłumieniem a autentycznością. Metafora Don Carlosa w filmie Leontine Sagan Dziewczęta w mundurkach [Between Suppression and Authenticity. The Metaphor of Don Carlos in Leontine Sagan’s Movie Mädchen in Uniform]. „Przestrzenie Teorii” 32. Poznań 2019, Adam Mickiewicz University Press, pp. 143–166. ISSN 1644-6763. DOI 10.14746/pt.2019.32.7. The article is a comprehensive analysis of the intertextual references to Frederick Schiller’s tragedy Don Carlos in Leontine Sagan’s movie Girls in Uniform (Mädchen in Uniform, 1931). The author considers the complex circumstances of the cooperation between the director and the artistic director, Carl Froelich, during the production. Moreover, she also presents the literary basis for the movie, namely the tragedy by Christy Winsloe (Gestern und Heute – Yesterday and Today). On this basis, the author analyses the multilevel presence of two phenomena in the movie: sup- pression and authenticity, which are related to the metaphor of Don Carlos and the plot of love between two women. The contexts for the analysis are inspired by research in the anthropology of romanticism, psychoanalysis, the psychology of sexual identity, and research on the works of Frederick Schiller. KEYWORDS: Weimar Republic Cinema, intertextuality, homotextuality, suppression, authenticity, woman director Nakręcone w 1931 roku Dziewczęta w mundurkach (Mädchen in Uni- form) są balansującym -

We Do Not Want to Die: Word to Oreste Palella (Expanded Dreyer in Progress, I)

We do not want to die: Word to Oreste Palella (Expanded Dreyer in progress, I) 79 Oreste Palella, Messina, the Mafia alla “polentoni”, emphasize the goodness of sbarra director, it came to the character the merger between the cold rationalism of Marshal power [in Se dotta e abban - of the north and the heat of the south. donata , 1964] after being preached, he They will be three love stories to affirm says, to that of Vincenzo Ascalone [...]. the need to compose, between north And as a director? “I have not had the and south, the new Italian family. » boom but have never been a mediocre. Giacomo Gambetti, Sedotta e Being an actor in fifty years is an expe - abbandonata di Pietro Germi , rience that inspired me so many things, Cappelli, Bologna, 1964 and that will serve me well as a film - maker. [...] Indirectly the Germi movie was helped also to my Mafia alla sbar - CATERINA DA SIENA ra . In fact, after In nome della Legge , Director: Oreste Palella; story: Fernan - after Il cam mino della speranza it is do Leonardi; screenplay: F. Leonar di, O. born the problem of seeing Sicily; I Palella; cinematography: Alfredo Lupo; could not imitate it, I could not make it music: Leopoldo Perez Bonsignore, last; nor lush, all beautiful like in Jessica G.C. Carignani; cast: Regana De Liguo - [Jean Negulesco, 1962], for which I ro, Rina De Liguoro, Teresa Ma riani, directed the second unit.” [...] Oreste Ugo Sasso, Guido Gentilini; produc - Palella directed the first film in 1946, tion : L. Perez Bonsignore per Cigno Caterina da Siena , under the name of Film; country: Italia, 1947; format: “Orestes” (“because, he explains, was a 35mm, b/n; length: 92’. -

Lesbian Broadway: American Theatre and Culture, 1920-1945

Lesbian Broadway: American Theatre and Culture, 1920-1945 by Meghan Brodie Gualtieri This thesis/dissertation document has been electronically approved by the following individuals: Gainor,J Ellen (Chairperson) Bathrick,David (Minor Member) Villarejo,Amy (Minor Member) LESBIAN BROADWAY: AMERICAN THEATRE AND CULTURE, 1920-1945 A Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of Cornell University In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy by Meghan Brodie Gualtieri August 2010 © 2010 Meghan Brodie Gualtieri LESBIAN BROADWAY: AMERICAN THEATRE AND CULTURE, 1920-1945 Meghan Brodie Gualtieri, Ph.D. Cornell University 2010 Lesbian Broadway: American Theatre and Culture, 1920-1945 is a project of reclamation that begins to document a history of lesbianism on Broadway. Using drama about lesbianism as its vehicle, this study investigates white, middle-class, female homosexuality in the United States from 1920 to 1945 and explores the convergence of Broadway drama, lesbianism, feminism, sexology, eugenics, and American popular culture. While the methodologies employed here vary by chapter, the project as a whole reflects a cultural excavation and analysis of lesbian dramas in their appropriate socio-historical contexts and suggests new critical approaches for studying this neglected collection of plays. Chapter One re-visits the feminist possibilities of realism, specifically lesbian realist drama of the 1920s and 30s, in order to reconsider how genre, feminist criticism, and historical context can inform socio-sexual readings of lesbian drama. Building on this foundation, Chapter Two explores a series of lesbian characters on Broadway that undermines and frequently reverses dominant sexological assumptions about the nature of and threats posed by lesbianism. -

Revista Der Querschnitt

REVISTA DER QUERSCHNITT 1924 Der Querschnitt, a. 4, no 2/3, Verão. Berlim: Galeria Simon e Flechtheim Capa: litografia por Picasso. 1o encarte entre pp. 100-101 – Fotografia, retrato, s.d. Legenda: “Raymond Radiguet”. Necrológio 1903-1923. – Reprodução de obra, pintura, 1897. Legenda: “Henri Rousseau. La bohémienne endormie [A cigana adormecida]”. Foto: Galeria Simon (seleção e clichê), Antuérpia. – Reprodução de obra, pintura, 1897. Legenda: “Pierre-Auguste Renoir. Am Meer [No mar]”. Foto: Barnes Foundation, Filadélfia (clichê de Paul Guillaume). – Fotografia, mobília, s.d. Legenda: “Pierre Roussel. [Pequena cômoda à Luís XV]”. 1723-178 Foto: Flatow & Priemer, Berlim. – Reprodução de obra, pintura, s.d. Legenda: “WandbiLd in der ViLLa Item bei Pompei. [MuraL na Villa Item em Pompeia]”, (helênico). Foto: Extraída de Ernst Pfhul. MaLerei und Zeichnung der Griechen [‟Pintura e desenho dos gregosˮ], s.d, F. Bruckmann A. G., Munique. – Fotografia, teatro, s.d. Legenda: “Marc Chagall. BühnenbiLd zu Agenten im jüdischen Kammertheater SchoLom Aleichum in Moskau. [Cenografia para Agenten [Agentes] no teatro de câmara judaico SchoLom Aleichum, Moscou]”. Foto: – – Fotografia, teatro, s.d. Legenda: “Bühnenbild zu Carl Sternheim Nebbich, Kammerspiele Rosen, Berlin. [Cenografia para Nebbich [Que pena], conhecida como Mops, de Carl Sternheim, Kammerspiele Rosen, Berlim]”. Foto: Zander & Labisch. 2o encarte entre pp. 116-117 2 – Reprodução de obra, pintura, s.d. Legenda: “Édouard Manet. Le père Lathuile [O pai Lathuile]”. Pastel. Foto: Galeria Flechtheim, Berlim. – Fotografia, automóvel, s.d. Legenda: “Sechssitziger Reise Phaëton. [Phäton de seis Lugares]”. Foto: Clichê Szawe. – Reprodução de obra, fototipia, s.d. Legenda: “Egon Schiele. StiLLeben [Natureza morta]”. Aquarela. Foto: Associação Wurble, Viena. – Fotografia, cinema, s.d. -

Moma Weimar Cinema 1919-1933 Daydreams and Nightmares

MoMA PRESENTS THE MOST EXTENSIVE EXHIBITION OF WEIMAR CINEMA EVER MOUNTED IN THE UNITED STATES Four-Month Exhibition Includes Over 80 Films, Many Rare, a Selection of Original Weimar Movie Posters, and the Release of New Publication Weimar Cinema, 1919–1933: Daydreams and Nightmares November 17, 2010–March 7, 2011 The Roy and Niuta Titus Theaters NEW YORK, 29, 2010— The Museum of Modern Art, in association with the Friedrich-Wilhelm- Murnau Foundation in Wiesbaden and in cooperation with the Deutsche Kinemathek in Berlin, presents Weimar Cinema, 1919–1933: Daydreams and Nightmares, the most comprehensive exhibition surveying the extraordinarily fertile and influential period in German filmmaking between the two world wars. It was during this period that film matured from a silent, visually expressive art into one circumscribed yet enlivened by language, music and sound effects. This four-month series includes 75 feature-length films and 6 shorts―a mix of classic films and many motion pictures unseen since the 1930s―and opens with the newly discovered film Ins Blaue Hinein (Into the Blue) (1929), by Eugene Schüfftan, the special effects artist and master cinematographer originally renowned for his work on Fritz Lang‘s Metropolis (1927). Running November 17, 2010 through March 7, 2011, Weimar Cinema is augmented by an exhibition of posters and photographs of Weimar filmmaking in The Roy and Niuta Titus Theater 1 Lobby Galleries and an illustrated publication, which includes an extensive filmography supplemented by German criticism and essays by leading scholars of the period. The film portion of the exhibition is organized by Laurence Kardish, Senior Curator, Department of Film, The Museum of Modern Art, and Eva Orbanz, Senior Curator, Special Projects, Deutsche Kinemathek – Museum für Film und Fernsehen.