We Do Not Want to Die: Word to Oreste Palella (Expanded Dreyer in Progress, I)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Zur Geschichte Des Italienischen Stummfilms

PD. Dr. Sabine Schrader Geschichte(n) des italienischen Stummfilms Sor Capanna 1919, S. 71 1896 Erste Vorführungen der Brüder Lumières in Rom 1905 Spielfilm La presa di Roma 1910-1915 Goldenes Zeitalter des italienischen Stummfilms 1920er US-amerikanische Übermacht 1926 Erste cinegiornali 1930 Erster italienischer Tonfilm XXXVII Mostra internazionale del Cinema Libero IL CINEMA RITROVATO Bologna 28.6.-5.7.2008 • http://www.cinetecadibologna.it/programmi /05cinema/programmi05.htm Istituto Luce a Roma • http://www.archivioluce.com/archivio/ Museo Nazionale del Cinema a Torino (Fondazione Maria Prolo) • http://www.museonazionaledelcinema.it/ • Alovisio, Silvio: Voci del silenzio. La sceneggiatura nel cinema muto italiano. Mailand / Turin 2005. • Redi, Riccardo: Cinema scritto. Il catalogo delle riviste italiane di cinema. Rom 1992. Vita Cinematografica 1912-7-15 Inferno (1911) R.: Francesco Bertolini / Adolfo Padovan / Giuseppe De Liguoro Mit der Musik von Tangerine Dream (2002) Kino der Attraktionen 1. „Kino der Attraktionen“ bis ca. 1906 2. Narratives Kino (etabliert sich zwischen 1906 und 1911) Gunning, Tom: „The Cinema of Attractions: Early Film, Its Spectator and the Avant-Garde”, in: Thomas Elsaesser (Hg.): Early Cinema: Space Frame Narrative. London 1990, S. 56-62 Vita Cinematografica 1913, passim Quo vadis? (1912/1913) R.: Enrico Guazzoni Mit der Musik von Umberto Petrin/ Nicola Arata La presa di roma (1905) Bernardini 1981 (2), 47. Cabiria (1914) R.: Giovanni Pastrone; Zwischentitel: u.a. D„Annunzio Kamera: u.a. Segundo de Chomòn -

Literature and Film of the Weimar Republic (In English Translation) OLLI@Berkeley, Spring 2019 Mondays, April 1—29, 2019 (5 Weeks), 10:00 A.M

Instructor: Marion Gerlind, PhD (510) 430-2673 • [email protected] Literature and Film of the Weimar Republic (in English translation) OLLI@Berkeley, Spring 2019 Mondays, April 1—29, 2019 (5 weeks), 10:00 a.m. — 12:30 p.m. University Hall 41B, Berkeley, CA 94720 In this interactive seminar we shall read and reflect on literature as well as watch and discuss films of the Weimar Republic (1919–33), one of the most creative periods in German history, following the traumatic Word War I and revolutionary times. Many of the critical issues and challenges during these short 14 years are still relevant today. The Weimar Republic was not only Germany’s first democracy, but also a center of cultural experimentation, producing cutting-edge art. We’ll explore some of the most popular works: Bertolt Brecht and Kurt Weill’s musical play, The Threepenny Opera, Joseph von Sternberg’s original film The Blue Angel, Irmgard Keun’s bestseller The Artificial Silk Girl, Leontine Sagan’s classic film Girls in Uniform, Erich Maria Remarque’s antiwar novel All Quiet on the Western Front, as well as compelling poetry by Else Lasker-Schüler, Gertrud Kolmar, and Mascha Kaléko. Format This course will be conducted in English (films with English subtitles). Your active participation and preparation is highly encouraged! I recommend that you read the literature in preparation for our sessions. I shall provide weekly study questions, introduce (con)texts in short lectures and facilitate our discussions. You will have the opportunity to discuss the literature/films in small and large groups. We’ll consider authors’ biographies in the socio-historical background of their work. -

"To Rely on Verdi's Harmonies and Not on Wagnerian Force." the Reception of Ltalian Cinema in Switzerland, 1 939-45

GIANNI HAVER "To Rely on Verdi's Harmonies and not on Wagnerian Force." The Reception of ltalian Cinema in Switzerland, 1 939-45 Adopting an approach that appeals to the study of reception means em- phasising an analysis of the discourses called forth by films rather than an analysis of the films themselves. To be analysed, these discourses must have left certain traces, although it is of course difficult to know what two spectators actually said to one another on leaving a cinema in L939. The most obvious, visible, and regular source of information are film reviews in the daily press. Reception studies have, moreover, often privileged such sources, even if some scholars have drawn attention to the lack of com- pliance between the expression of a cultured minority - the critics - and the consumption of mass entertainment (see Daniel 1972, 19; Lindeperg 1997, L4). L. *y view, the press inevitably ranks among those discourses that have to be taken into consideratiorL but it is indispensable to confront it with others. Two of these discourses merit particular attentiory namely that of the authorities, as communicated through the medium of censor- ship, and that of programming, which responds to rules that are chiefly commercial. To be sure, both are the mouthpieces of cultural, political, and economic elites. Accordingly, their discourses are govemed by the ruling classes, especially with regard to the topic and period under investiga- tion here: the reception of Italian cinema in Switzerland between 1939 and 1945. The possibilities of expressing opposition were practically ruled out, or at least muted and kept under control. -

Ivol. Blom Ft Fuoco Or the Fatal Portrait. the Xixth

VU Research Portal Il Fuoco or the fatal portrait : the XIXth century in the Italian silent cinema Blom, I.L. published in Iris : a journal of theory on image and 1992 document version Publisher's PDF, also known as Version of record Link to publication in VU Research Portal citation for published version (APA) Blom, I. L. (1992). Il Fuoco or the fatal portrait : the XIXth century in the Italian silent cinema. Iris : a journal of theory on image and, 55-66. General rights Copyright and moral rights for the publications made accessible in the public portal are retained by the authors and/or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. • Users may download and print one copy of any publication from the public portal for the purpose of private study or research. • You may not further distribute the material or use it for any profit-making activity or commercial gain • You may freely distribute the URL identifying the publication in the public portal ? Take down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact us providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. E-mail address: [email protected] Download date: 30. Sep. 2021 IvoL. Blom ft Fuoco or the Fatal Portrait. The XIXth Century in the Italian Silent Cinema Introduction «The femme fatale is almost always in décolleté. She is often armed with a hypodermic or aflacon of ether. She sinuously turns her serpent' s neck toward the spectator. -

Lesbians (On Screen) Were Not Meant to Survive

Lesbians (On Screen) Were not Meant to Survive Federica Fabbiani, Independent Scholar, Italy The European Conference on Media, Communication & Film 2017 Official Conference Proceedings Abstract My paper focuses on the evolution of the image of the lesbian on the screen. We all well know what can be the role of cinema in the structuring of the personal and collective imaginary and hence the importance of visual communication tools to share and spread lesbian stories "even" with a happy ending. If, in the first filmic productions, lesbians inevitably made a bad end, lately they are also able to live ‘happily ever after’. I do too believe that “cinema is the ultimate pervert art. It doesn't give you what you desire - it tells you how to desire” (Slavoy Žižek, 2006), that is to say that the lesbian spectator had for too long to operate a semantic reversal to overcome a performance deficit and to desire in the first instance only to be someone else, normal and normalized. And here it comes during the 2000s a commercial lesbian cinematography, addressed at a wider audience, which well interpret the actual trend, that most pleases the young audience (considering reliable likes and tweets on social networks) towards normality. It is still difficult to define precisely these trends: what would queer scholars say about this linear path toward a way of life that dares only to return to normality? No more eccentric, not abject, perhaps not even more lesbians, but 'only' women. Is this pseudo-normality (with fewer rights, protections, privileges) the new invisibility? Keywords: Lesbianism, Lesbian cinema, Queer cinema, LGBT, Lesbian iafor The International Academic Forum www.iafor.org Introduction I would try to trace how the representation of lesbians on screen has developed over time. -

(Waco) Blaine R. Pasma MA Co-Mentor

ABSTRACT A Critical Analysis of Neorealism and Writing the Screenplay, Mid-Sized City (Waco) Blaine R. Pasma M.A. Co-Mentor: Christopher J. Hansen, M.F.A. Co-Mentor: James M. Kendrick, Ph.D. This thesis outlines both the historical and theoretical background to Italian neorealism and its influences specifically in global cinema and modern American independent cinema. It will also consist of a screenplay for a short film inspired by neorealist practices. Following this, a detailed script analysis will examine a variety of cinematic devices used and will be cross-examined with the research done before. The thesis will also include personal and professional goals. A Critical Analysis ofNeorealism and Writing the Screenplay, Mid-Sized City (Waco) by Blaine Pasma, B.A. A Thesis Approved by the Department of Film and Digital Media Christopher J. Hansen, M.F.A., Chairperson Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of Baylor University in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements forthe Degree of Master of Arts Approved by the Thesis Committee Christopher J. Hansen, M.F.A., Chairperson James M. Kendrick Ph.D., Chairperson Tiziano Cherubini, Ph.D. Accepted by the Graduate School May 2021 J. Larry Lyon, Ph.D., Dean Page bearing signatures is kept on file in the Graduate School. Copyright © 2021 by Blaine R. Pasma All rights reserved TABLE OF CONTENTS CHAPTER ONE .............................................................................................................................................. 1 INTRODUCTION ........................................................................................................................................... -

Where Can I Find Italian Silent Cinema? Ivo Blom 317 Chapter 30 Cinema on Paper: Researching Non-Filmic Materials Luca Mazzei 325

Italian Silent Cinema: AReader Edited by Giorgio Bertellini iv ITALIAN SILENT CINEMA: A READER British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data Italian Silent Cinema: A Reader A catalogue entry for this book is available from the British Library ISBN: 9780 86196 670 7 (Paperback) Cover: Leopoldo Metlicovitz’s poster for Il fuoco [The Fire, Itala Film, 1915], directed by Piero Fosco [Giovanni Pastrone], starring Pina Menichelli and Febo Mari. Courtesy of Museo Nazionale del Cinema (Turin). Credits Paolo Cherchi Usai’s essay, “A Brief Cultural History of Italian Film Archives (1980–2005)”, is a revised and translated version of “Crepa nitrato, tutto va bene”, that appeared in La Cineteca Italiana. Una storia Milanese ed. Francesco Casetti (Milan: Il Castoro, 2005), 11–22. Ivo Blom’s “All the Same or Strategies of Difference. Early Italian Comedy in International Perspective” is a revised version of the essay that was published with the same title in Il film e i suoi multipli/Film and Its Multiples, ed. Anna Antonini (Udine: Forum, 2003), 465–480. Sergio Raffaelli’s “On the Language of Italian Silent Films”, is a translation of “Sulla lingua dei film muti in Italia”, that was published in Scrittura e immagine. La didascalie nel cinema muto ed. Francesco Pitassio and Leonardo Quaresima (Udine: Forum, 1998), 187–198. These essays appear in this anthology by kind permission of their editors and publishers. Published by John Libbey Publishing Ltd, 3 Leicester Road, New Barnet, Herts EN5 5EW, United Kingdom e-mail: [email protected]; web site: www.johnlibbey.com Direct orders (UK and Europe): [email protected] Distributed in N. -

10 Wittman & Liebenberg Finalx

138 MÄDCHEN IN UNIFORM – GENDER, POWER AND SEXUALITY IN TIMES OF MILITARISATION Gerda-Elisabeth Wittmann North-West University, Potchefstroom Campus Ian Liebenberg Faculty of Military Science, Stellenbosch University Abstract The film Mädchen in Uniform (1931), a love story between a teacher and student in Germany, is widely recognised as the first pro-lesbian film. Banned by the National Socialists, it opened the way for pro-lesbian film production and was followed by films such as Acht Mädels im Boot (1932), Anna and Elisabeth (1933) and Ich für dich, du für mich (Me for You, You for Me, 1934). These films strongly contrasted with documentaries and popular films of the Third Reich that portrayed a new and heroic German nation growing from the ashes of defeat following the uneasy Peace of Versailles. The film Aimée & Jaguar (1999) revisited the theme of lesbian love during the National Socialist regime. Based on a true story, the film is a narrative of the love between a German and a Jewish woman. Despite controversy, the film won numerous prizes in Germany. This article investigates the portrayal of gender and power in Mädchen in Uniform and Aimée & Jaguar. It seeks to explain how lesbian women and the love between them were portrayed in a time of male domination, militarism and what was seen as hetero-normality. This contribution examines gender-related power struggles and the political climate in Germany at the time of the Weimar Republic and the build-up to National-Socialist militarism. Introduction This article deals with a case study of filmic art that illustrates the tensions between the somatic search for freedom and the constraints of a society that longed Scientia Militaria, South African for law, order, authority, and, if needs be, Journal of Military Studies, Vol military force. -

Muchachas-De-Uniforme.Pdf

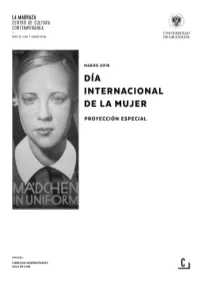

Sábado 9 marzo 20 h. DÍA INTERNACIONAL DE LA MUJER Sala Máxima del Espacio V Centenario Proyección Especial (Antigua Facultad de Medicina en Av. de Madrid) Entrada libre hasta completar aforo MUCHACHAS DE UNIFORME (1931) Alemania 83 min. Título Orig.- Mädchen in Uniform. Director.- Leontine Sagan & Carl Froelich. Argumento.- Las obras teatrales “Ritter Nérestan” (“Caballero Nérestan”, 1930) y “Gestern und Heuten” (“Ayer y hoy”, 1931) de Christa Winsloe. Guión.- Christa Winsloe y Friedrich Dammann. Fotografía.- Reimar Kuntze y Franz Weihmayr (1.20:1 – B/N). Montaje.- Oswald Hafenrichter. Música.- Hanson Milde-Meissner. Productor.- Carl Froelich y Friedrich Pflughaupt. Producción.- Deutsche Film- Gemeinschaft / Bild und Ton GmbH. Intérpretes.- Hertha Thiele (Manuela von Meinhardis), Dorothea Wieck (señorita von Bernburg), Hedwig Schlichter (señorita von Kesten), Ellen Schwanneke (Ilse von Westhagen), Emilia Unda (la directora), Erika Biebrach (Lilli von Kattner), Lene Berdoit (señorita von Gaerschner), Margory Bodker (señorita Evans), Erika Mann (señorita von Atems), Gertrud de Lalsky (tía de Manuela). Versión original en alemán con subtítulos en español Película nº 1 de la filmografía de Leontine Sagan (de 3 como directora) Premio del Público en el Festival de Venecia Música de sala: Berlin Cabaret songs Ute Lemper 3 En los primeros años de la historia cinematográfica alemana, la atracción entre mujeres en las películas mudas aparece sólo someramente, al margen y en la forma de Hosenrollen (muje- res con pantalones).1 En un momento de necesidad -

Il Fuoco Or the Fatal Portrait: the Xixth Century in the Italian Silent Cinema

IvoL. Blom ft Fuoco or the Fatal Portrait. The XIXth Century in the Italian Silent Cinema Introduction «The femme fatale is almost always in décolleté. She is often armed with a hypodermic or aflacon of ether. She sinuously turns her serpent' s neck toward the spectator. And - more rarely - having first revealed enormously wide eyes, she slowly veils them with soft lids, and before disappearing in the mist of afade-out risks the most daring gesture that can be shown on the screen ... Easy now ...! What I mean to say is that she slowly and guiltily bites her lower lip. (...) She also uses other weapons - I have already mentioned poison and drugs - such as the dagger, the revolver, the anonymous letter, andfinally, elegance. Elegance? I mean by elegance that which the woman who treads on hearts and devours brains can in no way do without: I) a clinging black velvet dress; 2) a dressing gown ofthe type known as «exotic» on which one often sees embroidery and designs of seaweed, insects, reptiles, and a death' s head; 3) afloral display that she tears at cruelly. (...) And between the apotheosis and the fall of the femme fatale, isn' t there room on the screenfor numerous passionate gestures? Numerous, to say the least. The two principal ones involve the hat and the rising gorge. Pretend that /' ve never seen them. The femme fatale' s hat spares her the necessity, at the absolute apex of her wicked career, ofhaving to expend herseifin pantomine. When the spectator sees the evil woman coiffing herseifwith a spread-winged owl, the head ofa stuffedjaguar, a bifid aigrette, or a hairy spida, he no longer has any doubts; he knows just what she is capable of And the rising gorge? The rising gorge is the imposing and ultimate means by which the evil woman informs the audience that she is about to weep, that she is hesitating on the brink of crime, that she is struggling against steely necessity, or that the police have Rotten their hands on the letter. -

The Early Generations of University Women in Fiction

This is a repository copy of Through Science to Selfhood? The Early Generations of University Women in Fiction.. White Rose Research Online URL for this paper: http://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/97686/ Version: Accepted Version Article: Bland, C. (2016) Through Science to Selfhood? The Early Generations of University Women in Fiction. Oxford German Studies, 45 (1). pp. 45-61. ISSN 0078-7191 https://doi.org/10.1080/00787191.2015.1128650 Reuse Unless indicated otherwise, fulltext items are protected by copyright with all rights reserved. The copyright exception in section 29 of the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988 allows the making of a single copy solely for the purpose of non-commercial research or private study within the limits of fair dealing. The publisher or other rights-holder may allow further reproduction and re-use of this version - refer to the White Rose Research Online record for this item. Where records identify the publisher as the copyright holder, users can verify any specific terms of use on the publisher’s website. Takedown If you consider content in White Rose Research Online to be in breach of UK law, please notify us by emailing [email protected] including the URL of the record and the reason for the withdrawal request. [email protected] https://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/ Through science to selfhood? The early generations of university women in fiction. Caroline Bland, University of Sheffield Abstract: The figure of the female student epitomized, for many German-speaking writers around 1900, the intellectual and social freedom supposedly enjoyed by the New Woman. -

Rezension Über: Jennifer Drake Askey, Good Girls, Good Germans. Girls' Education

Zitierhinweis Jacobi, Juliane: Rezension über: Jennifer Drake Askey, Good Girls, Good Germans. Girls’ Education and Emotional Nationalism in Wilhelminian Germany, New York: Camden House, 2013, in: German Historical Institute London Bulletin, Vol. XXXVI (2014), 2, S. 69-74, DOI: 10.15463/rec.1189742239, heruntergeladen über recensio.net First published: http://www.ghil.ac.uk/index.php?eID=tx_nawsecuredl=0 copyright Dieser Beitrag kann vom Nutzer zu eigenen nicht-kommerziellen Zwecken heruntergeladen und/oder ausgedruckt werden. Darüber hinaus gehende Nutzungen sind ohne weitere Genehmigung der Rechteinhaber nur im Rahmen der gesetzlichen Schrankenbestimmungen (§§ 44a-63a UrhG) zulässig. JENNIFER DRAKE ASKEY , Good Girls, Good Germans: Girls’ Edu - cation and Emotional Nationalism in Wilhelminian Germany , Studies in German Literature, Linguistics, and Culture (New York: Camden House, 2013), x + 201 pp. ISBN 978 1 57113 562 9. £55.00 The national education of young people in Imperial Germany has been widely studied. The author of the book under review here adds a new aspect to the theme: the emotional education of the daughters of the upper middle class (she herself speaks of the ‘middle class’ throughout) by reading relevant, nationally oriented literature, both inside and outside school. Referring to studies by Silvia Bovenschen, 1 Ute Frevert, 2 and Ruth-Ellen Boetcher Joeres, 3 Askey reports that the impact of misogynistic nineteenth-century German-language litera - ture on women has been sufficiently investigated, while middle-class girls remain largely invisible. What it meant for these future women to be exposed to this misogynistic literature is the subject of the four chapters comprising this book. The book starts with an outline of the development of secondary schooling for girls after the foundation of Imperial Germany, provid - ing the institutional framework within which the daughters of Prussia’s wealthy classes were imbued with a basic patriarchal un - derstanding of the world.