Endell Draft Article 18 Aug VCIB Converis Copy.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Scotland's Digital Media Company

Annual Report and Accounts 2010 Annual Report and Accounts Scotland’s digital media company 2010 STV Group plc STV Group plc In producing this report we have chosen production Pacific Quay methods which aim to minimise the impact on our Glasgow G51 1PQ environment. The papers chosen – Revive 50:50 Gloss and Revive 100 Uncoated contain 50% and 100% recycled Tel: 0141 300 3000 fibre respectively and are certified in accordance with the www.stv.tv FSC (Forest stewardship Council). Both the paper mill and printer involved in this production are environmentally Company Registration Number SC203873 accredited with ISO 14001. Directors’ Report Business Review 02 Highlights of 2010 04 Chairman’s Statement 06 A conversation with Rob Woodward by journalist and media commentator Ray Snoddy 09 Chief Executive’s Review – Scotland’s Digital Media Company 10 – Broadcasting 14 – Content 18 – Ventures 22 KPIs 2010-2012 24 Performance Review 27 Principal Risks and Uncertainties 29 Corporate Social Responsibility Corporate Governance 34 Board of Directors 36 Corporate Governance Report 44 Remuneration Committee Report Accounts 56 STV Group plc Consolidated Financial Statements – Independent Auditors’ Report 58 Consolidated Income Statement 58 Consolidated Statement of Comprehensive Income 59 Consolidated Balance Sheet 60 Consolidated Statement of Changes in Equity 61 Consolidated Statement of Cash Flows 62 Notes to the Financial Statements 90 STV Group plc Company Financial Statements – Independent Auditors’ Report 92 Company Balance Sheet 93 Statement -

The Westbourne Family Reunited Editorial Contents

Number 10 Autumn 2009 EThe magazinet for forcmer pupilse and friendst eof Glasgorw Academay and Westbourne School The Westbourne family reunited Editorial Contents 3 In the footsteps of greatness 4 The war years 6 Canada crossing 7 The Western Club: A haven in the city 8 Westbourne Section 10 Academical Club news 13 Events 16 How to half-succeed at The Academy 18 Moreton Black remembered 23 Tributes to John Anthony 24 Announcements 30 From our own correspondents Cheers! - Carol Shaw (1961), Jennifer Burgoyne (1968) and Vivien Heilbron (1961) at the Westbourne Grand Reunion 32 Regular Giving Some coffee morning! In February of this year a small committee led by the redoubtable Miss Betty Henderson got together to arrange what many assumed would turn out to be a coffee morning. Eight months - and a huge amount of work - later, 420 ‘girls’ met at the Grosvenor Hilton on Saturday 24 October for the Westbourne Grand Reunion. The evening was a great success, as you can tell from letters like the one below: Dear Joanna, I just want to say a very big ‘thank you’ to you and to everyone who organised the wonderful event Do we have your e-mail address? on Saturday evening. It was tremendous fun; it was very inspiring; it was a nostalgia feast and I shall never forget the decibel level achieved at the drinks party before the dinner itself! I'd liked to It’s how we communicate best! have made a recording for the archives. Alison Kennedy made a valiant effort to exert control and to her credit, in the main, she succeeded. -

Sci-Fi Sisters with Attitude Television September 2013 1 LOVE TV? SO DO WE!

April 2021 Sky’s Intergalactic: Sci-fi sisters with attitude Television www.rts.org.uk September 2013 1 LOVE TV? SO DO WE! R o y a l T e l e v i s i o n S o c i e t y b u r s a r i e s o f f e r f i n a n c i a l s u p p o r t a n d m e n t o r i n g t o p e o p l e s t u d y i n g : TTEELLEEVVIISSIIOONN PPRROODDUUCCTTIIOONN JJOOUURRNNAALLIISSMM EENNGGIINNEEEERRIINNGG CCOOMMPPUUTTEERR SSCCIIEENNCCEE PPHHYYSSIICCSS MMAATTHHSS F i r s t y e a r a n d s o o n - t o - b e s t u d e n t s s t u d y i n g r e l e v a n t u n d e r g r a d u a t e a n d H N D c o u r s e s a t L e v e l 5 o r 6 a r e e n c o u r a g e d t o a p p l y . F i n d o u t m o r e a t r t s . o r g . u k / b u r s a r i e s # R T S B u r s a r i e s Journal of The Royal Television Society April 2021 l Volume 58/4 From the CEO It’s been all systems winners were “an incredibly diverse” Finally, I am delighted to announce go this past month selection. -

![Statement 2011 [FINAL]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/9394/statement-2011-final-1129394.webp)

Statement 2011 [FINAL]

Statement 2011 Overall strategy / major themes for the year STV continues to thrive as Scotland’s most popular peak time TV station and holds the broadcast licences for central and north Scotland, attracting more than 4 million viewers each month. With a strong, recognisable brand and a flourishing production arm we enter 2011 in the best position possible to create and deliver and unique, rich and relevant schedule for our viewers. 2011 will see Scotland complete its digital switchover process which has already been achieved successfully in the STV north region. This brings increased choice to all viewers including a DTT HD version of STV, the result of new investment in order to offer Scotland’s most popular peaktime service at the highest resolution. The digital business has been a huge success for STV over the past 12 months and we are looking forward to bolstering this throughout 2011 and further cementing STV’s reputation as Scotland’s digital media company. Remaining at the core of STV’s strategy is our ongoing commitment to our quality content and making that content available to our audiences whenever, wherever and however they want it through our STV Anywhere program. We offer Scottish viewers a service that is both relevant and unique to Scotland and increasingly available on multi platforms including DTT, DSAT & DCAB and HD. To complement our on air transmissions, we are developing new access for viewers via online websites such as the STV Player and YouTube and serving content to mobile and connected devices starting with iPhone apps and PS3 consoles. -

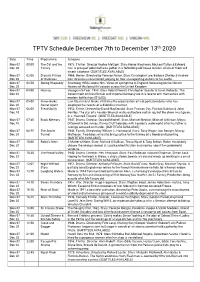

TPTV Schedule December 7Th to December 13Th 2020

th TPTV Schedule December 7th to December 13 2020 Date Time Programme Synopsis Mon 07 00:00 The Cat and the 1978. Thriller. Director Radley Metzger. Stars Honor Blackman, Michael Callan & Edward Dec 20 Canary Fox. A group of potential heirs gather in a forbidding old house to learn which of them will inherit a fortune. (SUBTITLES AVAILABLE) Mon 07 02:00 Dracula: Prince 1966. Horror. Directed by Terence Fisher. Stars Christopher Lee, Barbara Shelley & Andrew Dec 20 of Darkness Keir. Dracula is resurrected, preying on four unsuspecting visitors to his castle. Mon 07 03:50 Spring Rhapsody Charming 1950s colour film. Views of springtime in England, focussing on the vibrant Dec 20 flowers of this beautiful season across the United Kingdom Mon 07 04:00 Hannay Voyage into Fear. 1988. Stars Robert Powell, Christopher Scoular & Gavin Richards. The Dec 20 Government of Great Britain and Imperial Germany are in a race to arm themselves with modern battleships (S1,E03) Mon 07 05:00 Amos Burke: Law Steam Heat. Burke infiltrates the organization of a deported mobster who has Dec 20 Secret Agent employed the talents of a diabolical chemist. Mon 07 06:00 Tread Softly 1952. Crime. Directed by David MacDonald. Stars Frances Day, Patricia Dainton & John Dec 20 Bentley. The star of a London Musical walks out before curtain up, but the show must go on, in a 'Haunted Theatre'. (SUBTITLES AVAILABLE) Mon 07 07:30 Black Memory 1947. Drama. Director: Oswald Mitchell. Stars Michael Medwin, Michael Atkinson, Moyra Dec 20 O'Connell & Sid James. Danny Cruff hobnobs with London's underworld after his father is wrongly accused of murder. -

Home International: the Compass of Scottish Theatre Criticism

Home International: the Compass of Scottish Theatre Criticism Randall Stevenson An International Journal of Scottish Theatre, eh? Might not there be something faintly contradictory, even self-congratulatory, in that title, presuming an international interest in something of concern mostly locally? Any small nation might ask itself questions of this kind. For Scottish theatre, the answers have been reassuring recently, as the first numbers of IJOST helped confirm. Articles were sometimes international in subject – including analyses of theatrical translations into Scots – and also in origin, with studies of Scottish theatre by a number of critics working outside the country. With a growing number of Centres of Scottish Studies in France, Canada, the USA, Germany, Russia, Romania, and elsewhere around the globe – no doubt all happily accessing IJOST on the web – criticism of Scottish literature is now conducted thoroughly internationally, with drama, alongside poetry and the novel, increasingly taking its due share of this attention. Further evidence of this appeared in Scottish Theatre since the Seventies (1996), its contributors including critics of German, Greek, Nigerian and Irish origin, alongside, more predictably, commentators from England and from Scotland itself. Significantly, too, the most recent substantial study of Scottish theatre was edited and published in Italy. 1 So if Scottish drama is now regularly admired, studied, criticised – as well as often performed – beyond Scotland as well as within it, and now has its own International Journal, what more could we ask? Perhaps that this expanding critical readership should be more ready to locate drama genuinely internationally: to read Scottish plays more regularly within the wider context of world drama; of movements in the European theatre; of international models and influences. -

John Hawkesworth Scope and Content

JOHN HAWKESWORTH SCOPE AND CONTENT Papers relating to film and television producer, scriptwriter and designer JOHN STANLEY HAWKESWORTH. Born: London, 7 December 1920 Died: Leicester, 30 September 2003 John Hawkesworth was born the son of Lt.General Sir John Hawkesworth and educated at Rugby and Queen's College, Oxford. Between school and university he spent a year studying art at the Sorbonne in Paris, where Picasso corrected his drawings once a week. Following the military tradition of his family, Hawkesworth joined the Grenadier guards in 1940 and had a distinguished World War II record. In 1943 he married Hyacinth Gregson-Ellis and on demobilisation from the army began work in the film industry as an assistant to Vincent Korda. As art director he worked on many films for British Lion including The THIRD MAN (GB, 1949), OUTCAST OF THE ISLANDS (GB, 1951), and The SOUND BARRIER (GB, 1952). As a freelance designer he was involved with The MAN WHO NEVER WAS (GB, 1955) and The PRISONER (GB, 1955). Joining the Rank Organisation as a trainee producer, Hawkesworth worked on several films at Pinewood and was associate producer on WINDOMS WAY (GB, 1957) and TIGER BAY (GB, 1959). Hawkesworth's writing for television began with projects including HIDDEN TRUTH (tx 9/7/1964 - 6/10/1964), BLACKMAIL (Associated Rediffusion tx 1965 - 1966) and the 13 part BBC series CONAN DOYLE (tx 15/1/1967 - 23/4/1967), before embarking on the acclaimed LWT series The GOLDROBBERS (tx 6/6/1969 - 29/4/1969). It was with the latter that the Sagitta Production Company who were to produce the highly successful Edwardian series UPSTAIRS DOWNSTAIRS (tx 1970 - 1975) for LWT, came into existence, making Hawkesworth and his long term professional partner Alfred Shaughnessy household names. -

STV Review 2012 Overall Strategy / Major Themes for the Year STV Has

STV Review 2012 Overall Strategy / Major Themes for the Year STV has confirmed its place at the heart of communities and the creative industries in Scotland in 2012. The signing of new Channel 3 networking arrangements with ITV and the Secretary of State’s recommendation, in November to permit the long term renewal of the Channel 3 licences to STV in Central and North of Scotland has provided a strong platform for us to enhance the consumer experience and further build the STV brand. STV is committed to delivering high quality public service content that not only informs but engages its audience. It is imperative that we deliver a schedule that is distinct and relevant to Scotland, reflecting the cultural, political, sporting and wider differences that make the country unique. Our focus is to create and deliver a distinct schedule for viewers in Scotland - combining the best Channel 3 network material with a diverse range of original, relevant Scottish productions. STV reaches an average of 94% of Scots over the course of a month and on average attracts a higher audience share at peak time than the ITV network. STV News at Six is also currently achieving its highest audience share figures for 10 years. These are all clear indicators that STV is delivering programmes that are relevant and engaging for audiences across Scotland. Throughout 2012, STV’s transition from a traditional broadcaster to a digital media company has continued to develop as we make content readily available and free across multiple platforms anytime, anywhere. The creation of innovative, high quality and relevant material across new platforms remains key to our business and we continue to work with partners to deliver unique, compelling content wherever and whenever our consumers choose to access it. -

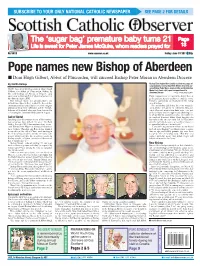

Pope Names New Bishop of Aberdeen � Dom Hugh Gilbert, Abbot of Pluscarden, Will Succeed Bishop Peter Moran in Aberdeen Diocese

SUBSCRIBE TO YOUR ONLY NATIONAL CATHOLIC NEWSPAPER SEE PAGE 2 FOR DETAILS No 5289 The ‘sugar bag’ premature baby turns 21 Page Life is sweet for Peter James McGuire, whom readers prayed for 13 No 5419 www.sconews.co.uk Friday June 10 2011 | 90p Pope names new Bishop of Aberdeen I Dom Hugh Gilbert, Abbot of Pluscarden, will succeed Bishop Peter Moran in Aberdeen Diocese By Martin Dunlop Bishop Elect Hugh Gilbert (main) received messages of congratulations from Cardinal Keith O’Brien (inset left), out- POPE Benedict XVI has named Dom Hugh going Bishop Peter Moran (inset middle) and Archbishop Gilbert, the abbot of Pluscarden Abbey, as Mario Conti (inset right) upon his appointment to the new bishop of Aberdeen Diocese and Aberdeen Diocese PICS: PAUL McSHERRY successor to Bishop Peter Moran who has led Hugh’s appointment is a loss to the abbey, there is the diocese since 2003. great gain for Aberdeen Diocese and the wider The Vatican made the announcement last Catholic community of Scotland in his being Saturday and Dom Gilbert, head of the Benedictine named bishop.” community at Pluscarden, has received the congrat- The archbishop added that the news would be ulations of his priestly colleagues and the Catholic ‘particularly welcomed in Aberdeen Diocese, bishops of Scotland, who now look forward to where Pluscarden has warm links with every part celebrating his Episcopal Ordination in August. of the territory and is recognised as a thriving cen- tre of spirituality, monastic practice and culture in Call of Christ the north of Scotland. Abbot Hugh has played a Speaking after the announcement of his nomina- key role in the success story that is Pluscarden tion as bishop, Dom Gilbert, 59, said: “The Holy over the last few decades, a period which has seen Father, Benedict XVI, has nominated me to suc- it expand its influence far and wide.’ ceed Bishop Peter Moran as bishop of Aberdeen. -

BA (Hons) Television

Please insert award – BA (Hons) Television PleaseMy Programme insert 2021/22the Programme Title 1 The Purpose of My Programme is to: Provide you with a source of information about your programme (which will be updated annually) and; Make you aware of some of the more important regulations under which your Programme operates. This document concentrates on Programme specific information. Members of your Programme Team (see section 4) will be happy to explain aspects in further detail as required. My Programme should be read alongside the My Napier resource, which contains useful information about the University as a whole. You can access My Napier at https://my.napier.ac.uk/ or by clicking any of the My Napier links in this document. The content of this My Programme is correct at the point of production however, due to the Covid-19 pandemic, some information may change. Please regularly check My Napier, student newsletters and university emails for important updates. For TNE provision there is a distinct My University handbook written for you and it replaces the My Napier references in this handbook. 2 1. Programme Leader Welcome Dr.Kirsten 0131 455 C5 [email protected] MacLeod 3343 As Programme Leader for BA Television, and on behalf of the BA (Hons) Television Programme Team, I would like to extend a very warm welcome to you. We look forward to working with you and supporting you during your time at Edinburgh Napier University. We hope you will be successful in your studies and make the most of all the opportunities that are available to you as a Napier student. -

Press Release 0700 Hours, 1 September 2020 STV Group Plc Half

RNS Number : 5533X STV Group PLC 01 September 2020 Press Release 0700 hours, 1 September 2020 STV Group plc Half Year Results to 30 June 2020 Strongly positioned to resume successful growth strategy • Proactive steps taken to mitigate the impact of Covid-19 and support STV colleagues and partners • Continued record viewing growth on TV and online as STV's public service broadcaster role is reinforced • Total advertising revenue trends improving materially: June -33%; July -7%; August +1% • Digital business accelerating rapidly with online viewing +86% • Significant new commissions secured by STV Studios, including new returnable drama series for C4 Proactive steps to mitigate the impact of Covid-19 • Balance sheet significantly strengthened to enable ongoing investment in STV's successful growth strategy: o Completion of share placing in July raising net proceeds of £15.5m o Extension of bank facilities from £60m to £80m • Swift implementation of full year cost and cash savings of £7m and £11m respectively, as well as postponement of pension contributions from Q2 to December • Focus in H1 has been on the safety of our colleagues and supporting our partners: all furloughed colleagues have been topped up to 100% of salary and we have reinforced our social purpose through the STV Children's Appeal, public health messaging, new diversity commitments and support for local advertisers Financial Performance •Total advertising revenue down 20%, with national down 23% and regional impacted to a lesser extent, down 18% • Digital revenues up 5%, -

The Scotch on the Rocks (BBC 1973) Controversy

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Royal Holloway - Pure John Hill ‘Political fantasy in a realistic situation’: the Scotch on the Rocks (BBC 1973) controversy Scotch on the Rocks was a five-part drama series broadcast by BBC1 in May and June 1973. It dealt with moves towards the creation of an independent Scotland and was referred to as a ‘political fantasy in a realistic situation’ by the BBC. The series was based on a novel co- written by Douglas Hurd, then political secretary to Conservative Prime Minister Ted Heath, and became the object of a running campaign and formal complaint by the Scottish National Party. This complaint was upheld by the BBC Programmes Complaints Commission with the result that the programme was never repeated and for a long time was believed to have been destroyed (though three episodes have now been discovered to exist). Although the programme’s effective disappearance has imbued it with a degree of mystique in certain quarters, there has so far been little serious discussion of it or the controversy that it generated. This article fills that gap by examining the political and broadcasting contexts in which the programme was produced, the criticisms directed at it and the curious ideological tensions evident in the series itself. In doing so the article identifies the peculiar position that the series occupies within the history of Scottish television drama and indicates how it may be understood as a work of greater interest than has so far been acknowledged.