The Scotch on the Rocks (BBC 1973) Controversy

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Scotland's 'Forgotten' Contribution to the History of the Prime-Time BBC1 Contemporary Single TV Play Slot Cook, John R

'A view from north of the border': Scotland's 'forgotten' contribution to the history of the prime-time BBC1 contemporary single TV play slot Cook, John R. Published in: Visual Culture in Britain DOI: 10.1080/14714787.2017.1396913 Publication date: 2018 Document Version Author accepted manuscript Link to publication in ResearchOnline Citation for published version (Harvard): Cook, JR 2018, ''A view from north of the border': Scotland's 'forgotten' contribution to the history of the prime- time BBC1 contemporary single TV play slot', Visual Culture in Britain, vol. 18, no. 3, pp. 325-341. https://doi.org/10.1080/14714787.2017.1396913 General rights Copyright and moral rights for the publications made accessible in the public portal are retained by the authors and/or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. Take down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please view our takedown policy at https://edshare.gcu.ac.uk/id/eprint/5179 for details of how to contact us. Download date: 26. Sep. 2021 1 Cover page Prof. John R. Cook Professor of Media Department of Social Sciences, Media and Journalism Glasgow Caledonian University 70 Cowcaddens Road Glasgow Scotland, United Kingdom G4 0BA Tel.: (00 44) 141 331 3845 Email: [email protected] Biographical note John R. Cook is Professor of Media at Glasgow Caledonian University, Scotland. He has researched and published extensively in the field of British television drama with specialisms in the works of Dennis Potter, Peter Watkins, British TV science fiction and The Wednesday Play. -

'Pinkoes Traitors'

‘PINKOES AND TRAITORS’ The BBC and the nation, 1974–1987 JEAN SEATON PROFILE BOOKS First published in Great Britain in !#$% by Pro&le Books Ltd ' Holford Yard Bevin Way London ()$* +,- www.pro lebooks.com Copyright © Jean Seaton !#$% The right of Jean Seaton to be identi&ed as the author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright Designs and Patents Act $++/. All rights reserved. Without limiting the rights under copyright reserved above, no part of this publication may be reproduced, stored or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means (electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise), without the prior written permission of both the copyright owner and the publisher of this book. A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library. ISBN +4/ $ /566/ 545 6 eISBN +4/ $ /546% +$6 ' All reasonable e7orts have been made to obtain copyright permissions where required. Any omissions and errors of attribution are unintentional and will, if noti&ed in writing to the publisher, be corrected in future printings. Text design by [email protected] Typeset in Dante by MacGuru Ltd [email protected] Printed and bound in Britain by Clays, Bungay, Su7olk The paper this book is printed on is certi&ed by the © $++6 Forest Stewardship Council A.C. (FSC). It is ancient-forest friendly. The printer holds FSC chain of custody SGS-COC-!#6$ CONTENTS List of illustrations ix Timeline xvi Introduction $ " Mrs Thatcher and the BBC: the Conservative Athene $5 -

BBC TV\S Panorama, Conflict Coverage and the Μwestminster

%%&79¶VPanorama, conflict coverage and WKHµ:HVWPLQVWHU FRQVHQVXV¶ David McQueen This copy of the thesis has been supplied on condition that anyone who consults it is understood to recognise that its copyright rests with its author and due acknowledgement must always be made of the use of any material contained in, or derived from, this thesis. %%&79¶VPanorama, conflict coverage and the µ:HVWPLQVWHUFRQVHQVXV¶ David Adrian McQueen A thesis in partial fulfilment of the requirements of Bournemouth University for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy August 2010 µLet nation speak peace unto nation¶ RIILFLDO%%&PRWWRXQWLO) µQuaecunque¶>:KDWVRHYHU@(official BBC motto from 1934) 2 Abstract %%&79¶VPanoramaFRQIOLFWFRYHUDJHDQGWKHµ:HVWPLQVWHUFRQVHQVXV¶ David Adrian McQueen 7KH%%&¶VµIODJVKLS¶FXUUHQWDIIDLUVVHULHVPanorama, occupies a central place in %ULWDLQ¶VWHOHYLVLRQKLVWRU\DQG\HWVXUSULVLQJO\LWLVUHODWLYHO\QHJOHFWHGLQDFDGHPLF studies of the medium. Much that has been written focuses on Panorama¶VFRYHUDJHRI armed conflicts (notably Suez, Northern Ireland and the Falklands) and deals, primarily, with programmes which met with Government disapproval and censure. However, little has been written on Panorama¶VOHVVFRQWURYHUVLDOPRUHURXWLQHZDUUeporting, or on WKHSURJUDPPH¶VPRUHUHFHQWKLVWRU\LWVHYROYLQJMRXUQDOLVWLFSUDFWLFHVDQGSODFHZLWKLQ the current affairs form. This thesis explores these areas and examines the framing of war narratives within Panorama¶VFRYHUDJHRIWKH*XOIFRQIOLFWV of 1991 and 2003. One accusation in studies looking beyond Panorama¶VPRUHFRQWHQWLRXVHSLVRGHVLVWKDW -

198J. M. Thornton Phd.Pdf

Kent Academic Repository Full text document (pdf) Citation for published version Thornton, Joanna Margaret (2015) Government Media Policy during the Falklands War. Doctor of Philosophy (PhD) thesis, University of Kent. DOI Link to record in KAR https://kar.kent.ac.uk/50411/ Document Version UNSPECIFIED Copyright & reuse Content in the Kent Academic Repository is made available for research purposes. Unless otherwise stated all content is protected by copyright and in the absence of an open licence (eg Creative Commons), permissions for further reuse of content should be sought from the publisher, author or other copyright holder. Versions of research The version in the Kent Academic Repository may differ from the final published version. Users are advised to check http://kar.kent.ac.uk for the status of the paper. Users should always cite the published version of record. Enquiries For any further enquiries regarding the licence status of this document, please contact: [email protected] If you believe this document infringes copyright then please contact the KAR admin team with the take-down information provided at http://kar.kent.ac.uk/contact.html Government Media Policy during the Falklands War A thesis presented by Joanna Margaret Thornton to the School of History, University of Kent In partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the subject of History University of Kent Canterbury, Kent January 2015 ©Joanna Thornton All rights reserved 2015 Abstract This study addresses Government media policy throughout the Falklands War of 1982. It considers the effectiveness, and charts the development of, Falklands-related public relations’ policy by departments including, but not limited to, the Ministry of Defence (MoD). -

The Westbourne Family Reunited Editorial Contents

Number 10 Autumn 2009 EThe magazinet for forcmer pupilse and friendst eof Glasgorw Academay and Westbourne School The Westbourne family reunited Editorial Contents 3 In the footsteps of greatness 4 The war years 6 Canada crossing 7 The Western Club: A haven in the city 8 Westbourne Section 10 Academical Club news 13 Events 16 How to half-succeed at The Academy 18 Moreton Black remembered 23 Tributes to John Anthony 24 Announcements 30 From our own correspondents Cheers! - Carol Shaw (1961), Jennifer Burgoyne (1968) and Vivien Heilbron (1961) at the Westbourne Grand Reunion 32 Regular Giving Some coffee morning! In February of this year a small committee led by the redoubtable Miss Betty Henderson got together to arrange what many assumed would turn out to be a coffee morning. Eight months - and a huge amount of work - later, 420 ‘girls’ met at the Grosvenor Hilton on Saturday 24 October for the Westbourne Grand Reunion. The evening was a great success, as you can tell from letters like the one below: Dear Joanna, I just want to say a very big ‘thank you’ to you and to everyone who organised the wonderful event Do we have your e-mail address? on Saturday evening. It was tremendous fun; it was very inspiring; it was a nostalgia feast and I shall never forget the decibel level achieved at the drinks party before the dinner itself! I'd liked to It’s how we communicate best! have made a recording for the archives. Alison Kennedy made a valiant effort to exert control and to her credit, in the main, she succeeded. -

The History of the Development of British Satellite Broadcasting Policy, 1977-1992

THE HISTORY OF THE DEVELOPMENT OF BRITISH SATELLITE BROADCASTING POLICY, 1977-1992 Windsor John Holden —......., Submitted in accordance with the requirements for the degree of PhD University of Leeds, Institute of Communications Studies July, 1998 The candidate confirms that the work submitted is his own and that appropriate credit has been given where reference has been made to the work of others ABSTRACT This thesis traces the development of British satellite broadcasting policy, from the early proposals drawn up by the Home Office following the UK's allocation of five direct broadcast by satellite (DBS) frequencies at the 1977 World Administrative Radio Conference (WARC), through the successive, abortive DBS initiatives of the BBC and the "Club of 21", to the short-lived service provided by British Satellite Broadcasting (BSB). It also details at length the history of Sky Television, an organisation that operated beyond the parameters of existing legislation, which successfully competed (and merged) with BSB, and which shaped the way in which policy was developed. It contends that throughout the 1980s satellite broadcasting policy ceased to drive and became driven, and that the failure of policy-making in this time can be ascribed to conflict on ideological, governmental and organisational levels. Finally, it considers the impact that satellite broadcasting has had upon the British broadcasting structure as a whole. 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS Abstract i Contents ii Acknowledgements 1 INTRODUCTION 3 British broadcasting policy - a brief history -

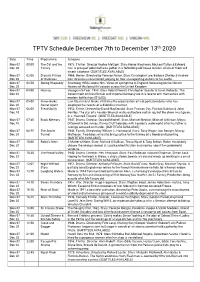

TPTV Schedule December 7Th to December 13Th 2020

th TPTV Schedule December 7th to December 13 2020 Date Time Programme Synopsis Mon 07 00:00 The Cat and the 1978. Thriller. Director Radley Metzger. Stars Honor Blackman, Michael Callan & Edward Dec 20 Canary Fox. A group of potential heirs gather in a forbidding old house to learn which of them will inherit a fortune. (SUBTITLES AVAILABLE) Mon 07 02:00 Dracula: Prince 1966. Horror. Directed by Terence Fisher. Stars Christopher Lee, Barbara Shelley & Andrew Dec 20 of Darkness Keir. Dracula is resurrected, preying on four unsuspecting visitors to his castle. Mon 07 03:50 Spring Rhapsody Charming 1950s colour film. Views of springtime in England, focussing on the vibrant Dec 20 flowers of this beautiful season across the United Kingdom Mon 07 04:00 Hannay Voyage into Fear. 1988. Stars Robert Powell, Christopher Scoular & Gavin Richards. The Dec 20 Government of Great Britain and Imperial Germany are in a race to arm themselves with modern battleships (S1,E03) Mon 07 05:00 Amos Burke: Law Steam Heat. Burke infiltrates the organization of a deported mobster who has Dec 20 Secret Agent employed the talents of a diabolical chemist. Mon 07 06:00 Tread Softly 1952. Crime. Directed by David MacDonald. Stars Frances Day, Patricia Dainton & John Dec 20 Bentley. The star of a London Musical walks out before curtain up, but the show must go on, in a 'Haunted Theatre'. (SUBTITLES AVAILABLE) Mon 07 07:30 Black Memory 1947. Drama. Director: Oswald Mitchell. Stars Michael Medwin, Michael Atkinson, Moyra Dec 20 O'Connell & Sid James. Danny Cruff hobnobs with London's underworld after his father is wrongly accused of murder. -

Home International: the Compass of Scottish Theatre Criticism

Home International: the Compass of Scottish Theatre Criticism Randall Stevenson An International Journal of Scottish Theatre, eh? Might not there be something faintly contradictory, even self-congratulatory, in that title, presuming an international interest in something of concern mostly locally? Any small nation might ask itself questions of this kind. For Scottish theatre, the answers have been reassuring recently, as the first numbers of IJOST helped confirm. Articles were sometimes international in subject – including analyses of theatrical translations into Scots – and also in origin, with studies of Scottish theatre by a number of critics working outside the country. With a growing number of Centres of Scottish Studies in France, Canada, the USA, Germany, Russia, Romania, and elsewhere around the globe – no doubt all happily accessing IJOST on the web – criticism of Scottish literature is now conducted thoroughly internationally, with drama, alongside poetry and the novel, increasingly taking its due share of this attention. Further evidence of this appeared in Scottish Theatre since the Seventies (1996), its contributors including critics of German, Greek, Nigerian and Irish origin, alongside, more predictably, commentators from England and from Scotland itself. Significantly, too, the most recent substantial study of Scottish theatre was edited and published in Italy. 1 So if Scottish drama is now regularly admired, studied, criticised – as well as often performed – beyond Scotland as well as within it, and now has its own International Journal, what more could we ask? Perhaps that this expanding critical readership should be more ready to locate drama genuinely internationally: to read Scottish plays more regularly within the wider context of world drama; of movements in the European theatre; of international models and influences. -

John Hawkesworth Scope and Content

JOHN HAWKESWORTH SCOPE AND CONTENT Papers relating to film and television producer, scriptwriter and designer JOHN STANLEY HAWKESWORTH. Born: London, 7 December 1920 Died: Leicester, 30 September 2003 John Hawkesworth was born the son of Lt.General Sir John Hawkesworth and educated at Rugby and Queen's College, Oxford. Between school and university he spent a year studying art at the Sorbonne in Paris, where Picasso corrected his drawings once a week. Following the military tradition of his family, Hawkesworth joined the Grenadier guards in 1940 and had a distinguished World War II record. In 1943 he married Hyacinth Gregson-Ellis and on demobilisation from the army began work in the film industry as an assistant to Vincent Korda. As art director he worked on many films for British Lion including The THIRD MAN (GB, 1949), OUTCAST OF THE ISLANDS (GB, 1951), and The SOUND BARRIER (GB, 1952). As a freelance designer he was involved with The MAN WHO NEVER WAS (GB, 1955) and The PRISONER (GB, 1955). Joining the Rank Organisation as a trainee producer, Hawkesworth worked on several films at Pinewood and was associate producer on WINDOMS WAY (GB, 1957) and TIGER BAY (GB, 1959). Hawkesworth's writing for television began with projects including HIDDEN TRUTH (tx 9/7/1964 - 6/10/1964), BLACKMAIL (Associated Rediffusion tx 1965 - 1966) and the 13 part BBC series CONAN DOYLE (tx 15/1/1967 - 23/4/1967), before embarking on the acclaimed LWT series The GOLDROBBERS (tx 6/6/1969 - 29/4/1969). It was with the latter that the Sagitta Production Company who were to produce the highly successful Edwardian series UPSTAIRS DOWNSTAIRS (tx 1970 - 1975) for LWT, came into existence, making Hawkesworth and his long term professional partner Alfred Shaughnessy household names. -

Strategic Change, Leadership and Accounting: a Triptych of Organizational Reform

Strategic Change, Leadership and Accounting: a triptych of organizational reform Abstract Strategic change in public sector organizations – especially in the form of increasing infiltration of ideas and practices emanating from the private sector – has been well documented. This article argues that accounting and other calculative practices have only been accorded limited roles in extant accounts of public sector strategic change initiatives. This article suggests that public management research would benefit from a greater appreciation of how calculative practices are deeply imbricated and constitutive of organizational life. In turn, the paper argues that the field of interdisciplinary accounting has much to learn from public administration, especially in terms of the latter’s engagement with leadership. The article’s overarching argument is that understanding strategic change in public organizations can be enhanced by bringing together insights from the academic fields of Public Administration and Interdisciplinary Accounting. This is particularly the case in circumstances where an accounting innovation is central to a strategic change programme. In this respect, organizational reform can be understood as a triptych, involving strategic change, leadership and accounting practices. We illustrate this thesis through a case study of strategic change in the world’s largest public service broadcaster – The British Broadcasting Corporation (BBC). It is demonstrated how, during the tenure of one organizational leader – John Birt - accounting technologies increasingly territorialized spaces, subjectivized individuals, mediated between the organization and the State, and permitted adjudication on what was efficient and value for money within the organization and what was not. Introduction This article seeks to analyse the interplay between leadership, strategic change and accounting. -

LJMU Research Online

LJMU Research Online Craig, MM Spycatcher’s Little Sister: The Thatcher government and the Panorama affair, 1980-81 http://researchonline.ljmu.ac.uk/id/eprint/4694/ Article Citation (please note it is advisable to refer to the publisher’s version if you intend to cite from this work) Craig, MM (2016) Spycatcher’s Little Sister: The Thatcher government and the Panorama affair, 1980-81. Intelligence and National Security, 32 (6). pp. 677-692. ISSN 1743-9019 LJMU has developed LJMU Research Online for users to access the research output of the University more effectively. Copyright © and Moral Rights for the papers on this site are retained by the individual authors and/or other copyright owners. Users may download and/or print one copy of any article(s) in LJMU Research Online to facilitate their private study or for non-commercial research. You may not engage in further distribution of the material or use it for any profit-making activities or any commercial gain. The version presented here may differ from the published version or from the version of the record. Please see the repository URL above for details on accessing the published version and note that access may require a subscription. For more information please contact [email protected] http://researchonline.ljmu.ac.uk/ Spycatcher’s Little Sister: The Thatcher government and the Panorama affair, 1980-811 Abstract: This article investigates the Thatcher government’s attempts to suppress or censor BBC reporting on secret intelligence issues in the early 1980s. It examines official reactions to a BBC intrusion into the secret world, as the team behind the long- running Panorama documentary strand sought to examine the role and accountability of Britain’s clandestine services. -

Doreen Stephens and BBC Television Programmes for Women, 1953–64 Mary Irwin

What Women Want on television:Bttlestar galactica / eric repphun Doreen stephens anD BBc television programmes for Women, 1953–64 Mary Irwin Doreen Stephens (1912–2001), editor of television programmes for women at the BBC between 1953 and 1964, is now almost entirely absent from histories of the BBC and, more generally, histories of early television. This article uses archive research, which brings together programme reconstruction and institutional and biographical research, to look at Stephens’ role in leading the expansion of women’s programmes, and to examine available traces of the difficult professional negotiations encountered in her attempts to broaden the range and quality of programmes that addressed women. Further, the article highlights the crucial importance of feminist archiving policies in ensuring both the preservation of women’s programmes and developing critical histories of television for women. KeyworDS: archives, BBC, feminist, Stephens, television, women Mary IrwIn: University of Warwick, UK 9999 What Women Want on television: Doreen stephens anD BBc television programmes for Women, 1953–64 Mary Irwin Doreen Stephens (1912–2001) was the first editor of BBC television women’s programmes at a time when the provision of television programmes for women had become a particular priority.1 She built up a specialist women’s programmes unit, creating and producing a highly diverse and ambitious weekly roster of television for women. Stephens and her team made television programmes which both acknowledged and addressed the complex post-war nexus of changing public and private roles and responsibilities which contemporary women faced, all the while defining and developing ideas around what television for women could and should be.