The Morphology and Behavior of Dimorphic Males in Perdita Portalis

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Insects and Related Arthropods Associated with of Agriculture

USDA United States Department Insects and Related Arthropods Associated with of Agriculture Forest Service Greenleaf Manzanita in Montane Chaparral Pacific Southwest Communities of Northeastern California Research Station General Technical Report Michael A. Valenti George T. Ferrell Alan A. Berryman PSW-GTR- 167 Publisher: Pacific Southwest Research Station Albany, California Forest Service Mailing address: U.S. Department of Agriculture PO Box 245, Berkeley CA 9470 1 -0245 Abstract Valenti, Michael A.; Ferrell, George T.; Berryman, Alan A. 1997. Insects and related arthropods associated with greenleaf manzanita in montane chaparral communities of northeastern California. Gen. Tech. Rep. PSW-GTR-167. Albany, CA: Pacific Southwest Research Station, Forest Service, U.S. Dept. Agriculture; 26 p. September 1997 Specimens representing 19 orders and 169 arthropod families (mostly insects) were collected from greenleaf manzanita brushfields in northeastern California and identified to species whenever possible. More than500 taxa below the family level wereinventoried, and each listing includes relative frequency of encounter, life stages collected, and dominant role in the greenleaf manzanita community. Specific host relationships are included for some predators and parasitoids. Herbivores, predators, and parasitoids comprised the majority (80 percent) of identified insects and related taxa. Retrieval Terms: Arctostaphylos patula, arthropods, California, insects, manzanita The Authors Michael A. Valenti is Forest Health Specialist, Delaware Department of Agriculture, 2320 S. DuPont Hwy, Dover, DE 19901-5515. George T. Ferrell is a retired Research Entomologist, Pacific Southwest Research Station, 2400 Washington Ave., Redding, CA 96001. Alan A. Berryman is Professor of Entomology, Washington State University, Pullman, WA 99164-6382. All photographs were taken by Michael A. Valenti, except for Figure 2, which was taken by Amy H. -

Bongisiwe Zozo

CAPE PENINSULA UNIVERSITY OF TECHNOLOGY Determination and characterisation of the function of black soldier fly larva protein before and after conjugation by Maillard reaction Bongisiwe Zozo Thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree Master of Applied Science in Chemistry in the Faculty of Applied Science Supervisor Prof Merrill Wicht (CPUT, Department of Chemistry) Co-Supervisor Prof Jessy van Wyk (CPUT, Department of Food Science and Technology) August 2020 CPUT copyright information The thesis may not be published either in part (in scholarly, scientific or technical journals), or as a whole (as a monograph), unless permission has been obtained from the University. DECLARATION I, Bongisiwe Zozo, declare that the content of this thesis represents my own unaided work, and that the thesis has not previously been submitted for academic examination towards any qualification. Furthermore, it represents my own opinions and not necessarily those of the Cape Peninsula University of Technology. Bongisiwe Zozo 31 August 2020 Signed Dated i ABSTRACT The increasing global population and consumer demand for protein will render the provision of protein a serious future challenge, thus placing substantial pressure on the food industry to provide for the human population. The lower environmental impact of insect farming makes the consumption of insects such as Black soldier fly larvae (BSFL) an appealing solution, although consumers in developed countries often respond to the idea of eating insects with aversion. One approach to adapt consumers to insects as part of their diet is through application of making insect- based products in an unrecognised form. Nutritional value and structural properties of the BSFL flours (full fat and defatted) were assessed. -

Ecosystem Management Research in the Ouachita Mountains: Pretreatment Conditions and Preliminary Findings

United States Proceedings of the Symposium on Department of Agriculture Forest Service Ecosystem Management Research Southern Forest Experiment Station in the Ouachita Mountains: New Orleans, Pretreatment Conditions and Louisiana Preliminary Findings General Technical Report SO-I 12 ’ August 1994 Proceedings of the Symposium on ECOSYSTEM MANAGEMENT RESEARCH IN THE OUACHITA MOUNTAINS: PRETREATMENT CONDITIONS AND PRELIMINARY FINDINGS Hot Springs, Arkansas October 26-27, 1993 Compiled by James B. Baker Published by U.S. Department of Agriculture Forest Service Southern Forest Experiment Station New Orleans, Louisiana 1994 PREFACE In August 1990, USDA Forest Service researchers from the Southern Forest Experiment Station and resource managers from the Ouachita and Ozark National Forests embarked on a major ecosystem management (then called New Perspectives) research program aimed at formulating, implementing, and evaluating partial cutting methods in shortleaf pine-hardwood stands as alternatives to clearcutting and planting. The program consisted of three phases: Phase I-an umeplicated stand-level demonstration project; Phase II-a scientifically based, replicated stand-level study; and Phase III-a large-scale watershed or landscape study. Harvesting treatments for the stand-level (Phase II) study were implemented during the summer of 1993. However, soon after the test stands were selected in 1990, pretreatment monitoring of various parameters was begun by a research team comprised of more than 50 scientists and resource managers from several -

Behavioral Ecology Symposium '97: Lloyd

Behavioral Ecology Symposium ’97: Lloyd 261 ON RESEARCH AND ENTOMOLOGICAL EDUCATION II: A CONDITIONAL MATING STRATEGY AND RESOURCE- SUSTAINED LEK(?) IN A CLASSROOM FIREFLY (COLEOPTERA: LAMPYRIDAE; PHOTINUS) JAMES E. LLOYD Department of Entomology and Nematology, University of Florida, Gainesville 32611 ABSTRACT The Jamaican firefly Photinus pallens (Fabricius) offers many opportunities and advantages for students to study insect biology in the field, and do research in taxon- omy and behavioral ecology; it is one of my four top choices for teaching. The binomen may hide a complex of closely related species and an interesting taxonomic problem. The P. pallens population I observed gathers in sedentary, flower-associated swarms which apparently are sustained by the flowers. Males and females remained together on the flowers for several hours before overt sexual activity began, and then pairs cou- pled quickly and without combat or display. Males occasionally joined and left the swarm, some flying and flashing over an adjacent field in a manner typical of North American Photinus species. Key Words: Lampyridae, Photinus, mating behavior, ecology RESUMEN La luciérnaga jamaiquina Photinus pallens (Fabricius) brinda muchas oportunida- des y ventajas a estudiantes para el estudio de la biología de los insectos en el campo y para la investigación sobre taxonomía y también sobre ecología del comportamiento; es una de las cuatro opciones principales elegidas para mi enseñanza. Este nombre bi- nomial puede que incluya un complejo de especies cercanamente relacionadas, que es un problema taxonómico interesante. La población de P. pallens que observé se reune en grupos sedentarios asociados con flores los cuales son aparentemente mantenidos por dichas flores. -

Bees of Ohio: a Field Guide

Bees of Ohio: A Field Guide North American Native Bee Collaborative The Bees of Ohio: A Field Guide (Version 1.1.1 , 5/2020) was developed based on Bees of Maryland: A Field Guide, authored by the North American Native Bee Collaborative Editing and layout for The Bees of Ohio : Amy Schnebelin, with input from MaLisa Spring and Denise Ellsworth. Cover photo by Amy Schnebelin Copyright Public Domain. 2017 by North American Native Bee Collaborative Public Domain. This book is designed to be modified, extracted from, or reproduced in its entirety by any group for any reason. Multiple copies of the same book with slight variations are completely expected and acceptable. Feel free to distribute or sell as you wish. We especially encourage people to create field guides for their region. There is no need to get in touch with the Collaborative, however, we would appreciate hearing of any corrections and suggestions that will help make the identification of bees more accessible and accurate to all people. We also suggest you add our names to the acknowledgments and add yourself and your collaborators. The only thing that will make us mad is if you block the free transfer of this information. The corresponding member of the Collaborative is Sam Droege ([email protected]). First Maryland Edition: 2017 First Ohio Edition: 2020 ISBN None North American Native Bee Collaborative Washington D.C. Where to Download or Order the Maryland version: PDF and original MS Word files can be downloaded from: http://bio2.elmira.edu/fieldbio/handybeemanual.html. -

Volume 26, Number 10, June 17, 2011 in This Week’S Issue

NC STATE UNIVERSITY Volume 26, Number 10, June 17, 2011 In This Week’s Issue . ANNOUNCEMENTS AND GENERAL INFORMATION . 1 CAUTION ! • Hay Field Day Scheduled for July 19 in Waynesville The information and FIELD AND FORAGE CROPS . 2 recommendations in • General Cotton Insect Outlook this newsletter are applicable to North • Plant Bugs on Cotton Carolina and may not • Spider Mites on Cotton apply in other areas. • Cotton Aphids • Cotton and Soybean Insect Scouting Schools • Kudzu Bugs Found in More North Carolina Counties Stephen J. Toth, Jr., • Voliam Xpress and Prevathon Now Registered in North Carolina editor ORNAMENTALS AND TURF . 7 Dept. of Entomology, • Kudzu Bugs on Ornamental Plants North Carolina State University, Box 7613, • Bagworms Active in Raleigh Raleigh, NC 27695 • Its Name Is Mud Dauber • Nano Pesticides Are Not Overlooked (919) 513-8189 Phone (919) 513-1114 Fax • Warm Season Spider Mites [email protected] See current and archived issues of the North Carolina Pest News on the Internet at: http://ipm.ncsu.edu/current_ipm/pest_news.html ANNOUNCEMENTS AND GENERAL INFORMATION Hay Field Day Scheduled for July 19 in Waynesville The Hay Field Day, sponsored by the North Carolina State University’s College of Agriculture and Life Sciences, will be held on Tuesday, July 19, 2011 at the Mountain Research Station in Waynesville, North Carolina. For more information, including a list of events and directions to the station, go to http://www.cals.ncsu.edu/agcomm/news-center/extension-news/n-c-hay- field-day-set-for-july-19/. North Carolina Pest News, June 17, 2011 Page 2 FIELD AND FORAGE CROPS From: Jack Bacheler, Extension Entomologist General Cotton Insect Outlook Even with our continued hot, dry weather, the cotton crop generally looks fair to good for most producers, but the crop is struggling in places. -

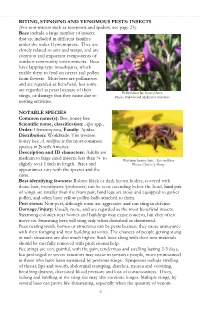

BITING, STINGING and VENOMOUS PESTS: INSECTS (For Non-Insects Such As Scorpions and Spiders, See Page 23)

BITING, STINGING AND VENOMOUS PESTS: INSECTS (For non-insects such as scorpions and spiders, see page 23). Bees include a large number of insects that are included in different families under the order Hymenoptera. They are closely related to ants and wasps, and are common and important components of outdoor community environments. Bees have lapping-type mouthparts, which enable them to feed on nectar and pollen from flowers. Most bees are pollinators and are regarded as beneficial, but some are regarded as pests because of their Pollination by honey bees stings, or damage that they cause due to Photo: Padmanand Madhavan Nambiar nesting activities. NOTABLE SPECIES Common name(s): Bee, honey bee Scientific name, classification: Apis spp., Order: Hymenoptera, Family: Apidae. Distribution: Worldwide. The western honey bee A. mellifera is the most common species in North America. Description and ID characters: Adults are medium to large sized insects, less than ¼ to Western honey bee, Apis mellifera slightly over 1 inch in length. Sizes and Photo: Charles J. Sharp appearances vary with the species and the caste. Best identifying features: Robust black or dark brown bodies, covered with dense hair, mouthparts (proboscis) can be seen extending below the head, hind pair of wings are smaller than the front pair, hind legs are stout and equipped to gather pollen, and often have yellow pollen-balls attached to them. Pest status: Non-pest, although some are aggressive and can sting in defense. Damage/injury: Usually none, and are regarded as the most beneficial insects. Swarming colonies near homes and buildings may cause concern, but they often move on. -

Sphecos: a Forum for Aculeate Wasp Researchers

SPHECOS Number 4 - January 1981 A Newsletter for Aculeate Wasp Researchers Arnold S. Menke, editor Systematic Entomology Laboratory, USDA c/o u. S. National Museum of Natural History washington DC 20560 Notes from the Editor This issue of Sphecos consists mainly of autobiographies and recent literature. A highlight of the latter is a special section on literature of the vespid subfamily Vespinae compiled and submitted by Robin Edwards (seep. 41). A few errors in issue 3 have been brought to my attention. Dr. Mickel was declared to be a "multillid" expert on page l. More seriously, a few typographical errors crept into Steyskal's errata paper on pages 43-46. The correct spellings are listed below: On page 43: p. 41 - Aneusmenus --- p. 108 - Zaschizon:t:x montana and z. Eluricincta On page 45: p. 940 - ----feminine because Greek mastix --- p. 1335 - AmEl:t:oEone --- On page 46: p. 1957 - Lasioglossum citerior My apologies to Dr. Mickel and George Steyskal. I want to thank Helen Proctor for doing such a fine job of typing the copy for Sphecos 3 and 4. Research News Ra:t:mond Wah is, Zoologie generale et Faunistique, Faculte des Sciences agronomiques, 5800 GEMBLOUX, Belgium; home address: 30 rue des Sept Collines 4930 CHAUDFONTAINE, Belgium (POMPILIDAE of the World), is working on a revision of the South American genus Priochilus and is also preparing an annotated key of the members of the Tribe Auplopodini in Australia (AuElOEUS, Pseudagenia, Fabriogenia, Phanagenia, etc.). He spent two weeks in London (British Museum) this summer studying type specimens and found that Turner misinterpreted all the old species and that his key (1910: 310) has no practical value. -

Male Mating Behaviour and Mating Systems of Bees: an Overview Robert John Paxton

Male mating behaviour and mating systems of bees: an overview Robert John Paxton To cite this version: Robert John Paxton. Male mating behaviour and mating systems of bees: an overview. Apidologie, Springer Verlag, 2005, 36 (2), pp.145-156. hal-00892131 HAL Id: hal-00892131 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-00892131 Submitted on 1 Jan 2005 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Apidologie 36 (2005) 145–156 © INRA/DIB-AGIB/ EDP Sciences, 2005 145 DOI: 10.1051/apido:2005007 Review article Male mating behaviour and mating systems of bees: an overview1 Robert John PAXTON* School of Biology and Biochemistry, Queen’s University Belfast, 97 Lisburn Road, Belfast BT9 7BL, UK Received 9 November 2004 – Accepted 9 December 2004 Published online 1 June 2005 Abstract – Considerable interspecific diversity exists among bees in the rendezvous sites where males search for females and in the behaviours employed by males in their efforts to secure matings. I present an evolutionary framework in which to interpret this variation, and highlight the importance for the framework of (i) the distribution of receptive (typically immediate post-emergence) females, which ordinarily translates into the distribution of nests, and (ii) the density of competing males. -

The Biology and External Morphology of Bees

3?00( The Biology and External Morphology of Bees With a Synopsis of the Genera of Northwestern America Agricultural Experiment Station v" Oregon State University V Corvallis Northwestern America as interpreted for laxonomic synopses. AUTHORS: W. P. Stephen is a professor of entomology at Oregon State University, Corval- lis; and G. E. Bohart and P. F. Torchio are United States Department of Agriculture entomolo- gists stationed at Utah State University, Logan. ACKNOWLEDGMENTS: The research on which this bulletin is based was supported in part by National Science Foundation Grants Nos. 3835 and 3657. Since this publication is largely a review and synthesis of published information, the authors are indebted primarily to a host of sci- entists who have recorded their observations of bees. In most cases, they are credited with specific observations and interpretations. However, information deemed to be common knowledge is pre- sented without reference as to source. For a number of items of unpublished information, the generosity of several co-workers is ac- knowledged. They include Jerome G. Rozen, Jr., Charles Osgood, Glenn Hackwell, Elbert Jay- cox, Siavosh Tirgari, and Gordon Hobbs. The authors are also grateful to Dr. Leland Chandler and Dr. Jerome G. Rozen, Jr., for reviewing the manuscript and for many helpful suggestions. Most of the drawings were prepared by Mrs. Thelwyn Koontz. The sources of many of the fig- ures are given at the end of the Literature Cited section on page 130. The cover drawing is by Virginia Taylor. The Biology and External Morphology of Bees ^ Published by the Agricultural Experiment Station and printed by the Department of Printing, Ore- gon State University, Corvallis, Oregon, 1969. -

Hymenoptera: Pteromalidae) on Various Potential Hosts

González et al.: Development of Dibrachys pelos 49 COMPARATIVE DEVELOPMENT AND COMPETITIVE ABILITY OF DIBRACHYS PELOS (HYMENOPTERA: PTEROMALIDAE) ON VARIOUS POTENTIAL HOSTS JORGE M. GONZÁLEZ, ROBERT W. MATTHEWS AND JANICE R. MATTHEWS Department of Entomology, University of Georgia, Athens, GA 30606 ABSTRACT Dibrachys pelos (Grissell) is an occasional gregarious ectoparasitoid of Sceliphron caemen- tarium (Drury). We report the second record of this host association, collected in western Ne- braska, and present results of laboratory experiments on host suitability and utilization. When D. pelos was reared alone on prepupae of 6 possible hosts, 4 proved entirely suitable: the mud dauber wasps Sceliphron caementarium and Trypoxylon politum Say, and two of their parasitoids, a velvet ant, Sphaeropthalma pensylvanica (Lepeletier) and a bee fly, An- thrax sp. On these hosts D. pelos completed development in 2-4 weeks, with average clutch sizes of 33-57, of which 24.7% were males. The other two hosts tested, the flesh fly Neobel- lieria bullata (Parker) and the leaf-cutter bee Megachile rotundata (Say), proved marginal, with very few adult progeny produced. When reared on these same 6 hosts with the addition of a competing parasitoid, Melittobia digitata Dahms, D. pelos fared poorly, being the sole offspring producer in at most 30% of the trials (on Anthrax hosts) and failing to prevail at all on T. politum hosts. Comparative data on host conversion efficiency indicated that M. digi- tata was more efficient than D. pelos on every host except Anthrax. Key Words: host conversion efficiency, interspecific competition, Melittobia digitata RESUMEN Dibrachys pelos (Grissell) es un ectoparasitoide gregario ocasional de Sceliphron caementa- rium (Drury). -

Insectiture Insects + Architecture

Insects + Architecture Insectiture But why build? Community Living: Resource Super-organism Microclimate claims er elt Food Sh ‘Cattle sheds’ storage Offspring Brood rearing launchpad The Honeybee Kingdom: Animalia Phylum: Arthropoda Class: Insecta Subclass: Pterygota Infraclass: Neoptera Superorder: Endopterygota Order: Hymenoptera Suborder: Apocrita Family: Apidae Subfamily: Apinae Tribe: Apini Genus: Apis Linnaeus, 1758 Honey bees are a subset of bees, primarily distinguished by the production and storage of honey and the construction of perennial, colonial nests out of wax. The Bee and the Hive… Young worker bees clean the hive and feed the larvae. They secrete royal jelly- which is protein rich- from glands on their heads When these glands begin to atrophy, they start building comb walls using wax from glands on their abdomens. They graduate to within colony tasks such as receiving pollen and nectar from foragers and guarding the hive Start flights for foraging, the wax glands atrophy. Remainder of the life is as a forager. Ingredients for the perfect Beehive… Beeswax: Is a natural was produced by the glands of young worker bees (these glands atrophy with age when the worker’s flights begin). This wax is initially transparent, but becomes opaque after the bees chew on it. It further gains a yellow color because of pollen and propolis. To produce this wax, a bee must consume eight times as much honey by mass (hence beekeepers usually return the wax after ‘robbing the bees’). *Beeswax is commercially used as an ingredient for moustache wax. Propolis: Is a resinous mixture collected by bees from tree buds, sap flows and other botanical sources.