ESRARA Newsletter

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Piasa, Or, the Devil Among the Indians

LI B RAFLY OF THE UNIVERSITY Of ILLINOIS THE PIASA, OR, BY HON. P. A. ARMSTRONG, AUTHOR OF "THE SAUKS, AND THE BLACK HAWK WAR," "I,EGEND OP STARVED ROCK," ETC. WITH ENGRAVINGS OF THE MONSTERS. MORRIS, E. B. FLETCHER, BOOK AND JOB PRINTER. 1887. HIST, CHAPTER I. PICTOGRAPHS AND PETROGLYPHS THEIR ORIGIN AND USES THE PIASA,*OR PIUSA,f THE LARGEST AND MOST WONDERFUL PETRO- GLYPHS OF THE WORLD THEIR CLOSE RESEMBLANCE TO THE MANIFOLD DESCRIPTIONS AND NAMES OF THE DEVIL OF THE SCRIPTURES WHERE, WHEN AND BY WHOM THESE MONSTER PETROGLYPHS WERE DISCOVERED BUT BY WHOM CONCEIVED AND EXECUTED, AND FOR WHAT PURPOSE, NOW IS, AND PROB- ABLY EVER WILL BE, A SEALED MYSTERY. From the evening and the morning of the sixth day, from the beginning when God created the heaven and the earth, and darkness was upon the face of the deep, and the spirit of God moved upon the face of the waters, and God said: Let there be light in the firmament of the heavens to divide the day .from the night, and give light upon the earth, and made two great lights, the greater to rule the day and the lesser to rule the night, and plucked from his jeweled crown a handful of dia- monds and scattered them broadcast athwart the sky for bril- liants to his canopy, and stars in his firmament, down through the countless ages to the present, all nations, tongues, kindreds and peoples, in whatsoever condition, time, clime or place, civilized,pagan, Mohammedan,barbarian or savage,have adopt- ed and utilized signs, motions, gestures, types, emblems, sym- bols, pictures, drawings, etchings or paintings as their primary and most natural as well as direct and forcible methods and vehicles of communicating, recording and perpetuating thought and history. -

APR 2 7 200I National Register of Historic Places Multiple Property Documentation Form

NPS Form 10^900-b OMB No. 1024-<X (Revised March 1992) United Skates Department of the Interior iatlonal Park Service APR 2 7 200I National Register of Historic Places Multiple Property Documentation Form This form Is used for documenting multiple property groups relating to one or several historic contexts. See Instructions in How to Complete t MuMple Property Documentation Form (National Register Bulletin 168). Complete each Item by entering the requested information. For additional space, use continuation sheets (Form 10-900-a). Use a typewriter, word processor, or computer to complete all Items. _X_ New Submission __ Amended Submission A. Name of Multiple Property Listing Native American Rock Art Sites of Illinois B. Associated Historic Contexts_______________________________ (Name each associated historic context, identifying theme, geographical area, and chronological period for each.) Native American Rock Art of Illinois (7000 B.C. - ca. A. D. 1835) C. Form Prepared by name/title Mark J. Wagner, Staff Archaeologist organization Center for Archaeological Investigations dat0 5/15/2000 Southern Illinois University street & number Mailcode 4527 telephone (618) 453-5035 city or town Carbondale state IL zip code 62901-4527 D. Certification As the designated authority under the National Historic Preservation Act of 1966, as amended, I hereby certify that this documentation form meets the National Register documentation standards and sets forth requirements for the listing of related properties consistent with the National Register criteria. This submission meets the procedural and professional requirements set forth In 36 CFR Part 60 and the Secretary of the Interior's Standards and Guidelines for Archeology and Historic Preservation. -

Archaeologist Volume 41 No

OHIO ARCHAEOLOGIST VOLUME 41 NO. 3 SUMMER 1991 The Archaeological Society of Ohio MEMBERSHIP AND DUES Annual dues to the Archaeological Society of Ohio are payable on the first of January as follows: Regular membership $15.00; husband and TERM wife (one copy of publication) $16.00; Life membership $300.00. EXPIRES A.S.O. OFFICERS Subscription to the Ohio Archaeologist, published quarterly, is included 1992 President James G. Hovan, 16979 South Meadow Circle, in the membership dues. The Archaeological Society of Ohio is an Strongsville, OH 44136, (216) 238-1799 incorporated non-profit organization. 1992 Vice President Larry L. Morris, 901 Evening Star Avenue SE, East Canton, OH 44730, (216) 488-1640 BACK ISSUES 1992 Exec. Sect. Barbara Motts, 3435 Sciotangy Drive, Columbus, Publications and back issues of the Ohio Archaeologist: OH 43221, (614) 898-4116 (work) (614) 459-0808 (home) Ohio Flint Types, by Robert N. Converse $ 6.00 1992 Recording Sect. Nancy E. Morris, 901 Evening Star Avenue Ohio Stone Tools, by Robert N. Converse $ 5.00 SE, East Canton, OH 44730, (216) 488-1640 Ohio Slate Types, by Robert N. Converse $10.00 1992 Treasurer Don F. Potter, 1391 Hootman Drive, Reynoldsburg, OH 43068, (614) 861-0673 The Glacial Kame Indians, by Robert N. Converse $15.00 1998 Editor Robert N. Converse, 199 Converse Dr., Plain City, OH Back issues—black and white—each $ 5.00 43064,(614)873-5471 Back issues—four full color plates—each $ 5.00 1992 Immediate Past Pres. Donald A. Casto, 138 Ann Court, Back issues of the Ohio Archaeologist printed prior to 1964 are Lancaster, OH 43130, (614) 653-9477 generally out of print but copies are available from time to time. -

Mid-America : an Historical Review

N %. 4' cyVLlB-zAMKRICA An Historical Review VOLUME 28. NUMBER 1 JANUARY 1946 ijA V ^ WL ''<^\ cTWID-cylMERICA An Historical Review JANUARY 1946 VOLUME 28 NEW SERIES, VOLUME 17 NUMBER I CONTENTS THE DISCOVERY OF THE MISSISSIPPI SECONDARY SOURCES J^^^' Dela/iglez 3 THE JOURNAL OF PIERRE VITRY, S.J /^^« Delanglez 23 DOCUMENT: JOURI>j^ OF FATHER VITRY OF THE SOCIETY OF JESUS. iARMY CHAPLAIN DURING THE WAR AGAINST THE CHIII^ASAW*. ]ea>j Delanglez 30 .' BOOK REVIEWS . .- 60 MANAGING EDITOR JEROME V. JACOBSEN, Chicago EDITORIAL STAFF WILLIAM STETSON MERRILL RAPHAEL HAMILTON J. MANUEL ESPINOSA PAUL KINIERY W. EUGENE SHIELS JEAN DELANGLEZ Published quarterly by Loyola University (The Institute of Jesuit History) at 50 cents a copy. Annual subscription, $2.00; in foreign countries, $2.50. Publication and editorial offices at Loyola University, 6525 Sheridan Road, Chicago, Illinois. All communications should be addressed to the Manag^ing Editor. Entered as second class matter, August 7, 1929, at the post oflnce at Chicago, Illinois, under the Act of March 3, 1879. Additional entry as second class matter at the post office at Effingham, Illinois. Printed in the United States. cTVIID-c^MERICA An Historical Review JANUARY 1946 VOLUME 28 NEW SERIES, VOLUME 17 NUMBER 1 The Discovery of the Mississippi Secondary Sources By secondary sources we mean the contemporary documents which are based on those mentioned in our previous article.^ The first of these documents contains one sentence not found in any of the extant accounts of the discovery of the Mississippi, thus pointing to the fact that the compiler had access to a presumably lost narrative of the voyage of 1673, or that he inserted in his account some in- formation which is found today on one of the maps illustrating the voyage of discovery. -

Rattlesnake Tales 127

Hamell and Fox Rattlesnake Tales 127 Rattlesnake Tales George Hamell and William A. Fox Archaeological evidence from the Northeast and from selected Mississippian sites is presented and combined with ethnographic, historic and linguistic data to investigate the symbolic significance of the rattlesnake to northeastern Native groups. The authors argue that the rattlesnake is, chief and foremost, the pre-eminent shaman with a (gourd) medicine rattle attached to his tail. A strong and pervasive association of serpents, including rattlesnakes, with lightning and rainfall is argued to have resulted in a drought-related ceremo- nial expression among Ontario Iroquoians from circa A.D. 1200 -1450. The Rattlesnake and Associates Personified (Crotalus admanteus) rattlesnake man-being held a special fascination for the Northern Iroquoians Few, if any of the other-than-human kinds of (Figure 2). people that populate the mythical realities of the This is unexpected because the historic range of North American Indians are held in greater the eastern diamondback rattlesnake did not esteem than the rattlesnake man-being,1 a grand- extend northward into the homeland of the father, and the proto-typical shaman and warrior Northern Iroquoians. However, by the later sev- (Hamell 1979:Figures 17, 19-21; 1998:258, enteenth century, the historic range of the 264-266, 270-271; cf. Klauber 1972, II:1116- Northern Iroquoians and the Iroquois proper 1219) (Figure 1). Real humans and the other- extended southward into the homeland of the than-human kinds of people around them con- eastern diamondback rattlesnake. By this time the stitute a social world, a three-dimensional net- Seneca and other Iroquois had also incorporated work of kinsmen, governed by the rule of reci- and assimilated into their identities individuals procity and with the intensity of the reciprocity and families from throughout the Great Lakes correlated with the social, geographical, and region and southward into Virginia and the sometimes mythical distance between them Carolinas. -

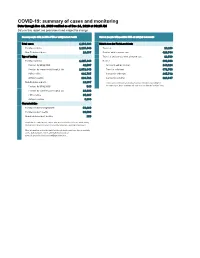

COVID-19: Summary of Cases and Monitoring Data Through Dec 13, 2020 Verified As of Dec 14, 2020 at 09:25 AM Data in This Report Are Provisional and Subject to Change

COVID-19: summary of cases and monitoring Data through Dec 13, 2020 verified as of Dec 14, 2020 at 09:25 AM Data in this report are provisional and subject to change. Cases: people with positive PCR or antigen test result Cases: people with positive PCR or antigen test result Total cases 1,134,383 Risk factors for Florida residents 1,115,446 Florida residents 1,115,446 Traveled 10,103 Non-Florida residents 18,937 Contact with a known case 426,744 Type of testing Traveled and contact with a known case 12,593 Florida residents 1,115,446 Neither 666,006 Positive by BPHL/CDC 42,597 No travel and no contact 140,324 Positive by commercial/hospital lab 1,072,849 Travel is unknown 371,766 PCR positive 991,735 Contact is unknown 265,742 Antigen positive 123,711 Contact is pending 224,647 Non-Florida residents 18,937 Travel can be unknown and contact can be unknown or pending for Positive by BPHL/CDC 545 the same case, these numbers will sum to more than the "neither" total. Positive by commercial/hospital lab 18,392 PCR positive 15,107 Antigen positive 3,830 Characteristics Florida residents hospitalized 58,269 Florida resident deaths 20,003 Non-Florida resident deaths 268 Hospitalized counts include anyone who was hospitalized at some point during their illness. It does not reflect the number of people currently hospitalized. More information on deaths identified through death certificate data is available on the National Center for Health Statistics website at www.cdc.gov/nchs/nvss/vsrr/COVID19/index.htm. -

The Holly Bluff Style

SOUTHEASTERN ARCHAEOLOGY, 2017 http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/0734578X.2017.1286569 The Holly Bluff style Vernon James Knight a, George E. Lankfordb, Erin Phillips c, David H. Dye d, Vincas P. Steponaitis e and Mitchell R. Childress f aDepartment of Anthropology, University of Alabama, Tuscaloosa, AL, USA; bRetired; cCoastal Environments, Inc., Baton Rouge, LA, USA; dDepartment of Earth Sciences, University of Memphis, Memphis, TN, USA; eDepartment of Anthropology, University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, NC, USA; fIndependent Scholar ABSTRACT ARTICLE HISTORY We recognize a new style of Mississippian-period art in the North American Southeast, calling it Received 11 November 2016 Holly Bluff. It is a two-dimensional style of representational art that appears solely on containers: Accepted 22 January 2017 marine shell cups and ceramic vessels. Iconographically, the style focuses on the depiction of KEYWORDS zoomorphic supernatural powers of the Beneath World. Seriating the known corpus of images Style; iconography; allows us to characterize three successive style phases, Holly Bluff I, II, and III. Using limited data, Mississippian; shell cups; we source the style to the northern portion of the lower Mississippi Valley. multidimensional scaling The well-known representational art of the Mississippian area in which Spiro is found. Using stylistic homologues period (A.D. 1100–1600) in the American South and in pottery and copper, Brown sourced the Braden A Midwest exhibits strong regional distinctions in styles, style, which he renamed Classic Braden, to Moorehead genres, and iconography. Recognizing this artistic phase Cahokia at ca. A.D. 1200–1275 (Brown 2007; regionalism in the past few decades has led to a new Brown and Kelly 2000). -

Proquest Dissertations

Recalling Cahokia: Indigenous influences on English commercial expansion and imperial ascendancy in proprietary South Carolina, 1663-1721 Item Type text; Dissertation-Reproduction (electronic) Authors Wall, William Kevin Publisher The University of Arizona. Rights Copyright © is held by the author. Digital access to this material is made possible by the University Libraries, University of Arizona. Further transmission, reproduction or presentation (such as public display or performance) of protected items is prohibited except with permission of the author. Download date 10/10/2021 06:16:12 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10150/298767 RECALLING CAHOKIA: INDIGENOUS INFLUENCES ON ENGLISH COMMERCIAL EXPANSION AND IMPERIAL ASCENDANCY IN PROPRIETARY SOUTH CAROLINA, 1663-1721. by William kevin wall A Dissertation submitted to the Faculty of the AMERICAN INDIAN STUDIES PROGRAM In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY In the Graduate College THE UNIVERSITY OF ARIZONA 2005 UMI Number: 3205471 INFORMATION TO USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleed-through, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. UMI UMI Microform 3205471 Copyright 2006 by ProQuest Information and Learning Company. All rights reserved. This microform edition is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code. ProQuest Information and Learning Company 300 North Zeeb Road P.O. -

What Effect Will the Aamd Guidelines Have on The

AMERICAN BAR ASSOCIATION SECTION OF INTERNATIONAL LAW SUMMER 2008, VOL. I, ISSUE NO. III WHAT EFFECT WILL THE AAMD GUIDELINES HAVE ON THE ANTIQUITIES MARKETS? By Erin Thompson, New York In 2004, an Italian court convicted Giacomo Medici, an Italian OFFICIADUNT citizen, of dealing in illicitly excavated antiquities. The fascinating story of Italy’s investigation into Medici and his antiquities smuggling ring is detailed in The Medici Conspiracy, a book by Peter Watson and Cecilia Todeschini. CONTENTS Medici and his accomplices kept meticulous records of the illicit antiquities which passed through their hands. Thanks to these TRAFFICKING NEWS records, Italy has recently successfully demanded the return of NOTES illegally-exported Italian antiquities from the collections of PAGE 3 American museums, including the Getty Museum, Boston Museum of Fine Arts, and Metropolitan Museum of Art. BARAKAT EXPLAINED In 2008, the American Association of Museum Directors PAGE 6 (“AAMD”), an influential professional organization, reacted to Italy’s aggressive repatriation demands by formulating a new set of RELOCATING THE guidelines for the purchase of antiquities (available at BARNES FOUNDATION www.aamd.org). The guidelines are not binding on member PAGE 10 museums, but several museums have released statements indicating that they will follow the AAMD’s recommendations. ON THE BEAT! The guidelines recommend that AAMD member museums should COMMITTEE NEWS AND not normally acquire an antiquity unless the museum’s own EVENTS research shows that the object left its country of origin before 1970, PAGE 13 the date of the relevant UNESCO Convention. This is an admirable change from the previous practice of relying on antiquities dealers DECLARATORY to provide information about the provenance and history of the JUDGMENTS AND objects they sold. -

Indian Head Rock Trial Set for May: Shaffer Faces Charges in Civil Case

The Ironton Tribune, Ohio Distributed by McClatchy-Tribune Business News February 23, 2010 Tuesday Indian Head Rock trial set for May: Shaffer faces charges in civil case BYLINE: Benita Heath, The Ironton Tribune, Ohio SECTION: STATE AND REGIONAL NEWS LENGTH: 461 words Feb. 23--ASHLAND, Ky. -- A court date has been set in the civil lawsuit against Ironton historian Steve Shaffer over his part in the removal of the Indian Head Rock from the Ohio River almost three years ago. Shaffer had faced criminal charges in Kentucky for removing an object of antiquity and/or defacing an archaeological site. However those charges were dropped in August 2009 in the courtroom of Greenup Circuit Judge Robert Conley when the state withdrew them on the grounds that the rock Shaffer had removed was not the historic object in question. As the criminal case was going forward, the Commonwealth of Kentucky filed the civil suit in February of 2009. Now that case is scheduled to come before U.S. District Judge Henry R. Wilhoit Jr. on May 11 in the federal building in Ashland. Kentucky is suing Shaffer, the city of Portsmouth, former Portsmouth Mayor Gregory Bauer and David Vetter, a diver involved in the rock expedition. "Kentucky was and is the rightful owner of the site in the Ohio River from which the Indian Head Rock was designated," the complaint states. "By removing Indian Head Rock from its archaeological site in the Ohio River without having first obtained a permit from the University of Kentucky Department of Anthropology, Defendants committed a violation of KRS 164.720." However in a motion filed this summer, Ashland-based attorney Mike Curtis, who represents Shaffer, argued that the rock Shaffer retrieved is not the Indian Head Rock. -

Intensive Cultural Resources Survey of the Legacy Austin Tract, Austin, Travis County, Texas

Volume 2020 Article 56 1-1-2020 Intensive Cultural Resources Survey of the Legacy Austin Tract, Austin, Travis County, Texas Jeffrey D. Owens Jesse O. Dalton Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.sfasu.edu/ita Part of the American Material Culture Commons, Archaeological Anthropology Commons, Environmental Studies Commons, Other American Studies Commons, Other Arts and Humanities Commons, Other History of Art, Architecture, and Archaeology Commons, and the United States History Commons Tell us how this article helped you. Cite this Record Owens, Jeffrey D. and Dalton, Jesse O. (2020) "Intensive Cultural Resources Survey of the Legacy Austin Tract, Austin, Travis County, Texas," Index of Texas Archaeology: Open Access Gray Literature from the Lone Star State: Vol. 2020, Article 56. ISSN: 2475-9333 Available at: https://scholarworks.sfasu.edu/ita/vol2020/iss1/56 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Center for Regional Heritage Research at SFA ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Index of Texas Archaeology: Open Access Gray Literature from the Lone Star State by an authorized editor of SFA ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Intensive Cultural Resources Survey of the Legacy Austin Tract, Austin, Travis County, Texas Creative Commons License This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License. This article is available in Index of Texas Archaeology: Open Access Gray Literature from the Lone Star State: https://scholarworks.sfasu.edu/ita/vol2020/iss1/56 Intensive Cultural Resources Survey of the Legacy Austin Tract, Austin, Travis County, Texas By: Jeffrey D. -

Sunday, March 29, 2009 Shawnee State University | Portsmouth, Ohio

Thirty-Second Annual Appalachian Studies Conference Friday, March 27 - Sunday, March 29, 2009 Shawnee State University | Portsmouth, Ohio Connecting Appalachia and the World through Traditional and Contemporary Arts, Crafts, and Music CONFERENCE PROGRAM 2009 ASA Conference Sponsors WELCOME! Anna M. Daehler Stillwell Fund through the Shawnee Welcome to the 2009 Appalachian Studies Association State University Development Foundation Conference and to Ohio Appalachia and our conference Anonymous Donor location on the campus of Shawnee State University in Appalachian Regional Commission Portsmouth, Ohio, at the confluence of the Scioto and Ohio Area Agency on Aging District 7, Inc. (Ohio) Rivers in south central Ohio. We hope that you will enjoy Berea College Appalachian Center the conference, the campus, and the community. Eastern Kentucky University Appalachian Center Jefferson Community College Carol Baugh, President Marshall University Deanna Tribe, Program Chair Ohio Appalachian Center for Higher Education Ginnie Moore, Local Arrangements Ohio Appalachian Task Force Ohio Arts Council Ohio Governor’s Office of Appalachia Ohio Humanities Council ASA MISSION STATEMENT Ohio State University Extension-Scioto County Ohio University Press The mission of the Appalachian Studies Association Our Common Heritage is to promote and engage dialogue, research, Shawnee State University scholarship, education, creative expression, and Sheila Oliver action among scholars, educators, practitioners, Sinclair Community College United Seniors of Athens County,