War Crimes by UK Forces in Iraq

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A New Age a Baby Born in the UK Tomorrow Can Expect to Live Five Hours Longer Than One Born Today

Issue 22 2010–11 A new age A baby born in the UK tomorrow can expect to live five hours longer than one born today. Why is that a problem? Inside: The naked truth with zoologist and artist Dr Desmond Morris. See pages 20–23 2 The Birmingham Magazine The fi rst word A question I’m often asked as Vice-Chancellor is what is the University’s vision for the future? Inevitably now, I expect that will be accompanied by inquiries as to what the recent announcements about UK higher education funding will mean for Birmingham. I believe the recommendations from the Browne The combination of deep public funding cuts When alumni ask me to outline the future of Review of Higher Education Funding and and the changes recommended by Lord Birmingham, I usually give the following answer. Student Support outline a fair and progressive Browne’s Independent Review herald a period system for prospective students. If adopted, it of unprecedented fi nancial turbulence for the Over the next fi ve years we will build on and would be graduates, not students, who contribute sector. At Birmingham we have anticipated diversify from our existing areas of excellence to the cost of their higher education, and only these changes, prepared, and made fi nancial to become an institution of international when they are in work and can afford it. A provision. Our new strategy sets out an preeminence. We will produce exceptional generous support package will be available for ambitious vision for our future, including our graduates and impactful research which makes students with the talent to take up a university plans to achieve continuing fi nancial strength. -

Fort Leavenworth Ethics Symposium

Fort Leavenworth Ethics Symposium Ethical and Legal Issues in Contemporary Conflict Symposium Proceedings Frontier Conference Center Fort Leavenworth, Kansas November 16-18, 2009 Edited by Mark H. Wiggins and Ted Ihrke Co-sponsored by the U.S. Army Command and General Staff College and the Command and General Staff College Foundation, Inc. Special thanks to our key corporate sponsor Other supporting sponsors include: Published by the CGSC Foundation Press 100 Stimson Ave., Suite 1149 Fort Leavenworth, Kansas 66027 Copyright © 2010 by CGSC Foundation, Inc. All rights reserved. www.cgscfoundation.org Papers included in this symposium proceedings book were originally submitted by military officers and other subject matter experts to the U.S. Army Command and General Staff College at Fort Leavenworth, Kansas. The CGSC Foundation/CGSC Foundation Press makes no claim to the authors’ copyrights for their individual work. ISBN 978-0-615-36738-5 Layout and design by Mark H. Wiggins MHW Public Relations and Communications Printed in the United States of America by Allen Press, Lawrence, Kansas iv Contents Acknowledgements ...................................................................................................................... ix Foreword by Brig. Gen. Ed Cardon, Deputy Commandant, CGSC & Col. (Ret.) Bob Ulin, CEO, CGSC Foundation ......................................................................... xi Symposium Participants ............................................................................................................ -

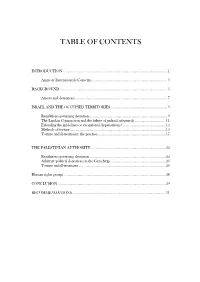

Table of Contents

TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION ...................................................................................................................... 1 Amnesty International's Concerns ..................................................................................... 3 BACKGROUND ......................................................................................................................... 5 Arrests and detentions ........................................................................................................ 7 ISRAEL AND THE OCCUPIED TERRITORIES ................................................................ 9 Regulations governing detention ........................................................................................ 9 The Landau Commission and the failure of judicial safeguards ................................. 11 Extending the guidelines or exceptional dispensations? ................................................ 14 Methods of torture ............................................................................................................ 15 Torture and ill-treatment: the practice ............................................................................. 17 THE PALESTINIAN AUTHORITY .................................................................................... 22 Regulations governing detention ...................................................................................... 22 Arbitrary political detentions in the Gaza Strip .............................................................. -

The Allied Occupation of Germany Began 58

City Research Online City, University of London Institutional Repository Citation: Abdullah, A.D. (2011). The Iraqi Media Under the American Occupation: 2003 - 2008. (Unpublished Doctoral thesis, City University London) This is the accepted version of the paper. This version of the publication may differ from the final published version. Permanent repository link: https://openaccess.city.ac.uk/id/eprint/11890/ Link to published version: Copyright: City Research Online aims to make research outputs of City, University of London available to a wider audience. Copyright and Moral Rights remain with the author(s) and/or copyright holders. URLs from City Research Online may be freely distributed and linked to. Reuse: Copies of full items can be used for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-profit purposes without prior permission or charge. Provided that the authors, title and full bibliographic details are credited, a hyperlink and/or URL is given for the original metadata page and the content is not changed in any way. City Research Online: http://openaccess.city.ac.uk/ [email protected] CITY UNIVERSITY Department of Journalism D Journalism The Iraqi Media Under the American Occupation: 2003 - 2008 By Abdulrahman Dheyab Abdullah Submitted 2011 Contents Acknowledgments 7 Abstract 8 Scope of Study 10 Aims and Objectives 13 The Rationale 14 Research Questions 15 Methodology 15 Field Work 21 1. Chapter One: The American Psychological War on Iraq. 23 1.1. The Alliance’s Representation of Saddam as an 24 International Threat. 1.2. The Technique of Embedding Journalists. 26 1.3. The Use of Media as an Instrument of War. -

Socialist Lawyer 43 (823KB)

LawyerI G SocialistMagazine of the Haldane Society of Socialist Lawyers Number 43 March 2006 £2.50 Guantánamo: Close it down Clive Stafford-Smith Haldane’s Plus: HELENA MICHAEL FINUCANE: Plus: PHIL SHINER, 75th KENNEDY ON ‘WHY NO PUBLIC CONOR GEARTY, birthday ‘THE RIGHTS INQUIRY OF MY ISRAELI WALL, see back page OF WOMEN’ FATHER’S MURDER?’ SECTION 9 & more HaldaneSocietyof SocialistLawyers PO Box 57055, London EC1P 1AF Contents Website: www.haldane.org Number 43 March 2006 ISBN 09 54 3635 The Haldane Society was founded in 1930. It provides a forum for the discussion and Guantánamo ...................................................................................................... 4 analysis of law and the legal system, both Clive Stafford Smith calls for the release of the eight Britons still held by the US nationally and internationally, from a socialist perspective. It holds frequent public meetings News & comment ................................................................................ 6 and conducts educational programmes. US lawyer Lynne Stewart; Abu Hamza and Nick Griffin; Colombian lawyers; and more The Haldane Society is independent of any political party. Membership comprises Young Legal Aid Lawyers ............................................ 11 lawyers, academics, students and legal Laura Janes explodes the myth of youth apathy workers as well as trade union and labour movement affiliates. Human rights and the war on terror .. 12 President: Michael Mansfield QC Professor Conor Gearty discusses the Human Rights Act -

Download Article

tHe ABU oMAr CAse And “eXtrAordinAry rendition” Caterina Mazza Abstract: In 2003 Hassan Mustafa Osama Nasr (known as Abu Omar), an Egyptian national with a recognised refugee status in Italy, was been illegally arrested by CIA agents operating on Italian territory. After the abduction he was been transferred to Egypt where he was in- terrogated and tortured for more than one year. The story of the Milan Imam is one of the several cases of “extraordinary renditions” imple- mented by the CIA in cooperation with both European and Middle- Eastern states in order to overwhelm the al-Qaeda organisation. This article analyses the particular vicissitude of Abu Omar, considered as a case study, and to face different issues linked to the more general phe- nomenon of extra-legal renditions thought as a fundamental element of US counter-terrorism strategies. Keywords: extra-legal detention, covert action, torture, counter- terrorism, CIA Introduction The story of Abu Omar is one of many cases which the Com- mission of Inquiry – headed by Dick Marty (a senator within the Parliamentary Assembly of the Council of Europe) – has investi- gated in relation to the “extraordinary rendition” programme im- plemented by the CIA as a counter-measure against the al-Qaeda organisation. The programme consists of secret and illegal arrests made by the police or by intelligence agents of both European and Middle-Eastern countries that cooperate with the US handing over individuals suspected of being involved in terrorist activities to the CIA. After their “arrest,” suspects are sent to states in which the use of torture is common such as Egypt, Morocco, Syria, Jor- dan, Uzbekistan, Somalia, Ethiopia.1 The practice of rendition, in- tensified over the course of just a few years, is one of the decisive and determining elements of the counter-terrorism strategy planned 134 and approved by the Bush Administration in the aftermath of the 11 September 2001 attacks. -

Sec 5.1~Abuse of Prisoners As Torture

1 5. Substantive Legal Assessment 5.1 Abuse of Prisoners as Torture and War Crimes under Sec. 8 of the CCIL and International Law The crimes described above against detainees at Abu Ghraib and the plaintiffs al Qahtani and Mowsboush constitute torture and war crimes under German and international criminal law. Therefore, sufficient evidence exists of criminality under Sec. 8 I nos. 3 and 9 CCIL. The following will provide a detailed legal analysis of the prohibitions in the CCIL and international law that were violated by the above-described acts. First, it will note the way in which two high-ranking members of the U.S. government dealt with the traditional torture techniques of “water boarding” and “longtime standing,” which is significant from the plaintiff’s perspective. In their publicly documented statements, both of government officials reveal a high degree of cynicism, coupled with ignorance of historical, legal and medical contexts. “Water Boarding” and “Longtime Standing” In the course of an interview on 24 October 2006, the Vice President of the United States, Richard Cheney, asked by radio reporter Scott Hennen whether “a dunk in water is a no- brainer if it can save lives,” gave the following answer: “It's a no-brainer for me, but for a 2 while there, I was criticized as being the ‘Vice President for torture.’ We don't torture. That's not what we're involved in. We live up to our obligations in international treaties that we're party to.” Cheney was the first member of the Bush government to admit that “water boarding” had been used in the case of detainee Khalid Scheikh Mohammed and other high-ranking al Quaeda members. -

Extraordinary Rendition and the Law of War

NORTH CAROLINA JOURNAL OF INTERNATIONAL LAW Volume 33 Number 4 Article 3 Summer 2008 Extraordinary Rendition and the Law of War Ingrid Detter Frankopan Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.law.unc.edu/ncilj Recommended Citation Ingrid D. Frankopan, Extraordinary Rendition and the Law of War, 33 N.C. J. INT'L L. 657 (2007). Available at: https://scholarship.law.unc.edu/ncilj/vol33/iss4/3 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Carolina Law Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in North Carolina Journal of International Law by an authorized editor of Carolina Law Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Extraordinary Rendition and the Law of War Cover Page Footnote International Law; Commercial Law; Law This article is available in North Carolina Journal of International Law: https://scholarship.law.unc.edu/ncilj/vol33/ iss4/3 Extraordinary Rendition and the Law of War Ingrid Detter Frankopant I. Introduction ....................................................................... 657 II. O rdinary R endition ............................................................ 658 III. Deportation, Extradition and Extraordinary Rendition ..... 659 IV. Essential Features of Extraordinary Rendition .................. 661 V. Extraordinary Rendition and Rfoulement ........................ 666 VI. Relevance of Legal Prohibitions of Torture ...................... 667 VII. Torture Flights, Ghost Detainees and Black Sites ............. 674 VIII. Legality -

Torture Flights : North Carolina’S Role in the Cia Rendition and Torture Program the Commission the Commission

TABLE OF CONTENTS TABLE OF CONTENTS 2 LIST OF COMMISSIONERS 4 FOREWORD Alberto Mora, Former General Counsel, Department of the Navy 6 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY A Summary of the investigation into North Carolina’s involvement in torture and rendition by the North Carolina Commission of Inquiry on Torture (NCCIT) 8 FINDINGS 12 RECOMMENDATIONS CHAPTER ONE 14 CHAPTER SIX 39 The U.S. Government’s Rendition, Detention, Ongoing Challenges for Survivors and Interrogation (RDI) Program CHAPTER SEVEN 44 CHAPTER TWO 21 Costs and Consequences of the North Carolina’s Role in Torture: CIA’s Torture and Rendition Program Hosting Aero Contractors, Ltd. CHAPTER EIGHT 50 CHAPTER THREE 26 North Carolina Public Opposition to Other North Carolina Connections the RDI Program, and Officials’ Responses to Post-9/11 U.S. Torture CHAPTER NINE 57 CHAPTER FOUR 28 North Carolina’s Obligations under Who Were Those Rendered Domestic and International Law, the Basis by Aero Contractors? for Federal and State Investigation, and the Need for Accountability CHAPTER FIVE 34 Rendition as Torture CONCLUSION 64 ENDNOTES 66 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS 78 APPENDICES 80 1 WWW.NCTORTUREREPORT.ORG TORTURE FLIGHTS : NORTH CAROLINA’S ROLE IN THE CIA RENDITION AND TORTURE PROGRAM THE COMMISSION THE COMMISSION THE COMMISSION THE COMMISSION FRANK GOLDSMITH (CO-CHAIR) JAMES E. COLEMAN, JR. PATRICIA MCGAFFAGAN DR. ANNIE SPARROW MBBS, MRCP, FRACP, MPH, MD Frank Goldsmith is a mediator, arbitrator and former civil James E. Coleman, Jr. is the John S. Bradway Professor Patricia McGaffagan worked as a psychologist for twenty rights lawyer in the Asheville, NC area. Goldsmith has of the Practice of Law, Director of the Center for five years at the Johnston County, NC Mental Health Dr. -

A Plan to Close Guantánamo and End the Military Commissions Submitted to the Transition Team of President-Elect Obama From

A Plan to Close Guantánamo and End the Military Commissions submitted to the Transition Team of President-elect Obama from the American Civil Liberties Union Anthony D. Romero Executive Director 125 Broad Street, 18th Floor New York, NY 10004 (212) 549-2500 January 2009 HOW TO CLOSE GUANTÁNAMO: A PLAN Introduction Guantánamo is a scourge on America and the Constitution. It must be closed. This document outlines a five-step plan for closing Guantánamo and restoring the rule of law. Secrecy and fear have distorted the facts about Guantánamo detainees. Our plan is informed by recognition of the following critical facts, largely unknown to the public: • The government has quietly repatriated two-thirds of the 750 detainees, tacitly admitting that many should never have been held at all. • Most of the remaining detainees will not be charged as terrorists, and can be released as soon as their home country or a haven country agrees to accept them. • Trying the remaining detainees in federal court – and thus excluding evidence obtained through torture or coercion – does not endanger the public. The rule of law and the presumption of innocence serve to protect the public. Furthermore, the government has repeatedly stated that there is substantial evidence against the detainees presumed most dangerous – the High Value Detainees – that was not obtained by torture or coercion. They can be brought to trial in federal court. I. Step One: Stay All Proceedings of the Military Commissions and Impose a Deadline for Closure The President should immediately -

Outlawed: Extraordinary Rendition, Torture and Disappearances in the War on Terror

Companion Curriculum OUTLAWED: Extraordinary Rendition, Torture and Disappearances in the War on Terror In Plain Sight: Volume 6 A WITNESS and Amnesty International Partnership www.witness.org www.amnestyusa.org Table of Contents 2 Table of Contents How to Use This Guide HRE 201: UN Convention against Torture Lesson One: The Torture Question Handout 1.1: Draw the Line Handout 1.2: A Tortured Debate - Part 1 Handout 1.3: A Tortured Debate - Part 2 Lesson Two: Outsourcing Torture? An Introduction to Extraordinary Rendition Resource 2.1: Introduction to Extraordinary Rendition Resource 2.2: Case Studies Resource 2.3: Movie Discussion Guide Resource 2.4: Introduction to Habeas Corpus Resource 2.5: Introduction to the Geneva Conventions Handout 2.6: Court of Human Rights Activity Lesson Three: Above the Law? Limits of Executive Authority Handout 3.1: Checks and Balances Timeline Handout 3.2: Checks and Balances Resource 3.3: Checks and Balances Discussion Questions Glossary Resources How to Use This Guide 3 How to Use This Guide The companion guide for Outlawed: Extraordinary Rendition, Torture, and Disappearances in the War on Terror provides activities and lessons that will engage learners in a discussion about issues which may seem difficult and complex, such as federal and international standards regarding treatment of prisoners and how the extraordinary rendition program impacts America’s success in the war on terror. Lesson One introduces students to the topic of torture in an age appropriate manner, Lesson Two provides background information and activities about extraordinary rendition, and Lesson Three examines the limits of executive authority and the issue of accountability. -

The UK and the Use of Force in Iraq: Academics and Policy-Makers

Adam Roberts The UK and the Use of Force in Iraq: Academics and Policy-Makers † Adam Roberts The role of outside forces in Iraq from 2003 onwards is, for the most part, an inglorious story of an initially successful use of military force that then ran into difficulties and ended largely in failure. Some might think it is best forgotten. However, there is always much to be learned from failure; and in this particular case, many questions of general and enduring interest are raised. These may be of interest to other countries, including China. The central questions I want to ask are simple. First, was the largely sceptical position of many UK academics in relation to this war justified? Has it been vindicated by the official reports on the war? What has been, or should now be, learned from the many failures of policy- making regarding Iraq? The invasion of Iraq in 2003 has deeply influenced UK and also US thinking about military action overseas. It contributed to a more general growth of scepticism in the UK and the US about a certain form of active international interventionism. It helps to explain the reluctance of both countries to intervene in the Syrian civil war from its beginnings in 2011 right through to the fall of the † Sir Adam Roberts, Emeritus Professor of International Relations, University of Oxford. Author’s statement: This paper is based on a talk at the Institute of International and Stra- tegic Studies, Peking University, Saturday, December 10, 2016 and the moderator is Yang Xiao (Suzanne Yang).