Safshekan Esfahani Roozbeh 201808 Phd

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A WAY FORWARD with IRAN? Options for Crafting a U.S. Strategy

A WAY FORWARD WITH IRAN? Options for Crafting a U.S. Strategy THE SOUFAN CENTER FEBRUARY 2021 A WAY FORWARD WITH IRAN? OPTIONS FOR CRAFTING A U.S. STRATEGY A WAY FORWARD WITH IRAN? Options for Crafting a U.S. Strategy THE SOUFAN CENTER FEBRUARY 2021 Cover photo: Associated Press Photo/Photographer: Mohammad Berno 2 A WAY FORWARD WITH IRAN? OPTIONS FOR CRAFTING A U.S. STRATEGY CONTENTS List of Abbreviations 4 List of Figures 5 Key Findings 6 How Did We Reach This Point? 7 Roots of the U.S.-Iran Relationship 9 The Results of the Maximum Pressure Policy 13 Any Change in Iranian Behavior? 21 Biden Administration Policy and Implementation Options 31 Conclusion 48 Contributors 49 About The Soufan Center 51 3 A WAY FORWARD WITH IRAN? OPTIONS FOR CRAFTING A U.S. STRATEGY LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS BPD Barrels Per Day FTO Foreign Terrorist Organization GCC Gulf Cooperation Council IAEA International Atomic Energy Agency ICBM Intercontinental Ballistic Missile IMF International Monetary Fund IMSC International Maritime Security Construct INARA Iran Nuclear Agreement Review Act INSTEX Instrument for Supporting Trade Exchanges IRGC Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps IRGC-QF Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps - Qods Force JCPOA Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action MBD Million Barrels Per Day PMF Popular Mobilization Forces SRE Significant Reduction Exception 4 A WAY FORWARD WITH IRAN? OPTIONS FOR CRAFTING A U.S. STRATEGY LIST OF FIGURES Figure 1: Iran Annual GDP Growth and Change in Crude Oil Exports 18 Figure 2: Economic Effects of Maximum Pressure 19 Figure 3: Armed Factions Supported by Iran 25 Figure 4: Comparison of Iran Nuclear Program with JCPOA Limitations 28 5 A WAY FORWARD WITH IRAN? OPTIONS FOR CRAFTING A U.S. -

The IRGC in the Age of Ebrahim Raisi: Decision-Making and Factionalism in Iran’S Revolutionary Guard

The IRGC in the Age of Ebrahim Raisi: Decision-Making and Factionalism in Iran’s Revolutionary Guard SAEID GOLKAR AUGUST 2021 KASRA AARABI Contents Executive Summary 4 The Raisi Administration, the IRGC and the Creation of a New Islamic Government 6 The IRGC as the Foundation of Raisi’s Islamic Government The Clergy and the Guard: An Inseparable Bond 16 No Coup in Sight Upholding Clerical Superiority and Preserving Religious Legitimacy The Importance of Understanding the Guard 21 Shortcomings of Existing Approaches to the IRGC A New Model for Understanding the IRGC’s Intra-elite Factionalism 25 The Economic Vertex The Political Vertex The Security-Intelligence Vertex Charting IRGC Commanders’ Positions on the New Model Shades of Islamism: The Ideological Spectrum in the IRGC Conclusion 32 About the Authors 33 Saeid Golkar Kasra Aarabi Endnotes 34 4 The IRGC in the Age of Ebrahim Raisi Executive Summary “The Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps [IRGC] has excelled in every field it has entered both internationally and domestically, including security, defence, service provision and construction,” declared Ayatollah Ebrahim Raisi, then chief justice of Iran, in a speech to IRGC commanders on 17 March 2021.1 Four months on, Raisi, who assumes Iran’s presidency on 5 August after the country’s June 2021 election, has set his eyes on further empowering the IRGC with key ministerial and bureaucratic positions likely to be awarded to guardsmen under his new government. There is a clear reason for this ambition. Expanding the power of the IRGC serves the interests of both Raisi and his 82-year-old mentor, Ayatollah Ali Khamenei, the supreme leader of the Islamic Republic. -

Policy Notes the Washington Institute for Near East Policy ■ 2019 ■ Pn58

POLICY NOTES THE WASHINGTON INSTITUTE FOR NEAR EAST POLICY ■ 2019 ■ PN58 SAEID GOLKAR THE SUPREME LEADER AND THE GUARD Civil-Military Relations and Regime Survival in Iran As the Islamic Republic concludes its fourth decade, the country faces three converging threats. The first involves its Supreme Leader, Ayatollah Ali Khamenei, who turns eighty this year and is, according to some reports, in poor health. The succession process could create a severe political struggle, possibly unsettling the entire regime. The second challenge is growing dissatisfaction among the population, evidenced by a rising incidence of strikes and protests throughout the country. These now occur daily. And the third has to do with economic hardships associated with the reimposition of U.S. sanctions, a development that could potentially exacerbate ongoing protests and further destabilize the regime. © 2019 THE WASHINGTON INSTITUTE FOR NEAR EAST POLICY. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED. SAEID GOLKAR To neutralize these threats, the Islamic Republic This study is divided into four sections. The first and the Supreme Leader are increasingly relying on examines the IRGC’s position and structure within their security and coercive mechanisms, foremost the Iran’s military. The second looks at the mechanisms Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps (IRGC) and its and strategies Ayatollah Khamenei uses to control civilian militia force, known as the Basij. Indeed, the the Guard, especially indoctrination, which is carried most important factor in the survival and transition out through entities known as ideological-political of political regimes is the loyalty of the armed forces. organizations (IPOs) across Iran’s military. This sec- Dictators cannot stay in power if they lose support tion outlines, in particular, the internal structure of the from their national military. -

Country Report Iran March 2017

_________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________ Country Report Iran Generated on November 13th 2017 Economist Intelligence Unit 20 Cabot Square London E14 4QW United Kingdom _________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________ The Economist Intelligence Unit The Economist Intelligence Unit is a specialist publisher serving companies establishing and managing operations across national borders. For 60 years it has been a source of information on business developments, economic and political trends, government regulations and corporate practice worldwide. The Economist Intelligence Unit delivers its information in four ways: through its digital portfolio, where the latest analysis is updated daily; through printed subscription products ranging from newsletters to annual reference works; through research reports; and by organising seminars and presentations. The firm is a member of The Economist Group. London New York The Economist Intelligence Unit The Economist Intelligence Unit 20 Cabot Square The Economist Group London 750 Third Avenue E14 4QW 5th Floor United Kingdom New York, NY 10017, US Tel: +44 (0) 20 7576 8181 Tel: +1 212 541 0500 Fax: +44 (0) 20 7576 8476 Fax: +1 212 586 0248 E-mail: [email protected] E-mail: [email protected] Hong Kong Geneva The Economist Intelligence Unit The Economist Intelligence Unit 1301 Cityplaza Four Rue de l’Athénée 32 12 Taikoo Wan Road 1206 Geneva Taikoo Shing Switzerland Hong Kong Tel: +852 2585 3888 Tel: +41 22 566 24 70 Fax: +852 2802 7638 Fax: +41 22 346 93 47 E-mail: [email protected] E-mail: [email protected] This report can be accessed electronically as soon as it is published by visiting store.eiu.com or by contacting a local sales representative. -

From the Editor

EDITORIAL STAFF From the Editor ELIZABETH SKINNER Editor Happy New Year, everyone. As I write this, we’re a few weeks into 2021 and there ELIZABETH ROBINSON Copy Editor are sparkles of hope here and there that this year may be an improvement over SALLY BAHO Copy Editor the seemingly endless disasters of the last one. Vaccines are finally being deployed against the coronavirus, although how fast and for whom remain big sticky questions. The United States seems to have survived a political crisis that brought EDITORIAL REVIEW BOARD its system of democratic government to the edge of chaos. The endless conflicts VICTOR ASAL in Syria, Libya, Yemen, Iraq, and Afghanistan aren’t over by any means, but they have evolved—devolved?—once again into chronic civil agony instead of multi- University of Albany, SUNY national warfare. CHRISTOPHER C. HARMON 2021 is also the tenth anniversary of the Arab Spring, a moment when the world Marine Corps University held its breath while citizens of countries across North Africa and the Arab Middle East rose up against corrupt authoritarian governments in a bid to end TROELS HENNINGSEN chronic poverty, oppression, and inequality. However, despite the initial burst of Royal Danish Defence College change and hope that swept so many countries, we still see entrenched strong-arm rule, calcified political structures, and stagnant stratified economies. PETER MCCABE And where have all the terrorists gone? Not far, that’s for sure, even if the pan- Joint Special Operations University demic has kept many of them off the streets lately. Closed borders and city-wide curfews may have helped limit the operational scope of ISIS, Lashkar-e-Taiba, IAN RICE al-Qaeda, and the like for the time being, but we know the teeming refugee camps US Army (Ret.) of Syria are busy producing the next generation of violent ideological extremists. -

Guardian Politics in Iran: a Comparative Inquiry Into the Dynamics of Regime Survival

GUARDIAN POLITICS IN IRAN: A COMPARATIVE INQUIRY INTO THE DYNAMICS OF REGIME SURVIVAL A Dissertation submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences of Georgetown University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Government By Payam Mohseni, M.A. Washington, DC June 22, 2012 Copyright 2012 by Payam Mohseni All Rights Reserved ii GUARDIAN POLITICS IN IRAN: A COMPARATIVE INQUIRY INTO THE DYNAMICS OF REGIME SURVIVAL Payam Mohseni, M.A. Thesis Advisor: Daniel Brumberg, Ph.D. ABSTRACT The Iranian regime has repeatedly demonstrated a singular institutional resiliency that has been absent in other countries where “colored revolutions” have succeeded in overturning incumbents, such as Ukraine, Georgia, Serbia, Kyrgyzstan and Moldova, or where popular uprisings like the current Arab Spring have brought down despots or upended authoritarian political landscapes, including Egypt, Tunisia, Yemen, Libya and even Syria. Moreover, it has accomplished this feat without a ruling political party, considered by most scholars to be the key to stable authoritarianism. Why has the Iranian political system proven so durable? Moreover, can the explanation for such durability advance a more deductive science of authoritarian rule? My dissertation places Iran within the context of guardian regimes—or hybrid regimes with ideological military, clerical or monarchical institutions steeped in the politics of the state, such as Turkey and Thailand—to explain the durability of unstable polities that should be theoretically prone to collapse. “Hybrid” regimes that combine competitive elections with nondemocratic forms of rule have proven to be highly volatile and their average longevity is significantly shorter than that of other regime types. -

134TH COMMENCEMENT James E

134 th Commencement MAY 2021 Welcome Dear Temple graduates, Congratulations! Today is a day of celebration for you and all those who have supported you in your Temple journey. I couldn’t be more proud of the diverse and driven students who are graduating this spring. Congratulations to all of you, to your families and to our dedicated faculty and academic advisors who had the pleasure of educating and championing you. If Temple’s founder Russell Conwell were alive to see your collective achievements today, he’d be thrilled and amazed. In 1884, he planted the seeds that have grown and matured into one of this nation’s great urban research universities. Now it’s your turn to put your own ideas and dreams in motion. Even if you experience hardships or disappointments, remember the motto Conwell left us: Perseverantia Vincit, Perseverance Conquers. We have faith that you will succeed. Thank you so much for calling Temple your academic home. While I trust you’ll go far, remember that you will always be part of the Cherry and White. Plan to come back home often. Sincerely, Richard M. Englert President UPDATED: 05/07/2021 Contents The Officers and the Board of Trustees ............................................2 Candidates for Degrees James E. Beasley School of Law ....................................................3 Esther Boyer College of Music and Dance .....................................7 College of Education and Human Development ...........................11 College of Engineering ............................................................... -

Us-Iran Tensions

U.S.-IRAN TENSIONS: IMPLICATIONS FOR HOMELAND SECURITY HEARING BEFORE THE COMMITTEE ON HOMELAND SECURITY HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES ONE HUNDRED SIXTEENTH CONGRESS SECOND SESSION JANUARY 15, 2020 Serial No. 116–57 Printed for the use of the Committee on Homeland Security Available via the World Wide Web: http://www.govinfo.gov U.S. GOVERNMENT PUBLISHING OFFICE 41–269 PDF WASHINGTON : 2020 VerDate Mar 15 2010 15:27 Sep 02, 2020 Jkt 000000 PO 00000 Frm 00001 Fmt 5011 Sfmt 5011 H:\116TH\20FL0115\20FL0115 HEATH Congress.#13 COMMITTEE ON HOMELAND SECURITY BENNIE G. THOMPSON, Mississippi, Chairman SHEILA JACKSON LEE, Texas MIKE ROGERS, Alabama JAMES R. LANGEVIN, Rhode Island PETER T. KING, New York CEDRIC L. RICHMOND, Louisiana MICHAEL T. MCCAUL, Texas DONALD M. PAYNE, JR., New Jersey JOHN KATKO, New York KATHLEEN M. RICE, New York MARK WALKER, North Carolina J. LUIS CORREA, California CLAY HIGGINS, Louisiana XOCHITL TORRES SMALL, New Mexico DEBBIE LESKO, Arizona MAX ROSE, New York MARK GREEN, Tennessee LAUREN UNDERWOOD, Illinois VAN TAYLOR, Texas ELISSA SLOTKIN, Michigan JOHN JOYCE, Pennsylvania EMANUEL CLEAVER, Missouri DAN CRENSHAW, Texas AL GREEN, Texas MICHAEL GUEST, Mississippi YVETTE D. CLARKE, New York DAN BISHOP, North Carolina DINA TITUS, Nevada BONNIE WATSON COLEMAN, New Jersey NANETTE DIAZ BARRAGA´ N, California VAL BUTLER DEMINGS, Florida HOPE GOINS, Staff Director CHRIS VIESON, Minority Staff Director (II) VerDate Mar 15 2010 15:27 Sep 02, 2020 Jkt 000000 PO 00000 Frm 00002 Fmt 5904 Sfmt 5904 H:\116TH\20FL0115\20FL0115 HEATH C O N T E N T S Page STATEMENTS The Honorable Bennie G. -

Buku Panduan Prasiswazah FSSK 20182019

The National University of Malaysia The National University of Malaysia Fakulti Sains Sosial dan Kemanusiaan / 1 PANDUAN PRASISWAZAH Fakulti Sains Sosial dan Kemanusiaan Sesi Akademik 2018-2019 2 /Panduan Prasiswazah Sesi Akademik 2018-2019 Fakulti Sains Sosial dan Kemanusiaan / 3 4 /Panduan Prasiswazah Sesi Akademik 2018-2019 PANDUAN PRASISWAZAH Fakulti Sains Sosial dan Kemanusiaan Sesi Akademik 2018-2019 Fakulti Sains Sosial dan Kemanusiaan Universiti Kebangsaan Malaysia Bangi 2018 http://www.fssk.ukm.my Fakulti Sains Sosial dan Kemanusiaan / 5 Cetakan / Printing Hak cipta / Copyright Universiti Kebangsaan Malaysia, 2012 Pihak Pengurusan Universiti sedaya upaya sudah mempastikan bahawa Buku Panduan ini adalah tepat pada masa diterbitkan. Buku ini bermaksud untuk memberikan panduan kepada pelajar memilih program dan kursus pengajian serta kemudahan yang ditawarkan dan tidak dimaksudkan sebagai satu ikatan kontrak. Pengurusan Universiti berhak meminda atau menarik balik tawaran dan kursus pengajian serta kemudahan tanpa sebarang notis. Diterbitkan di Malaysia oleh / Published in Malaysia by FAKULTI SAINS SOSIAL DAN KEMANUSIAAN Universiti Kebangsaan Malaysia 43600 UKM Bangi, Selangor D.E Malaysia. Dicetak di Malaysia / Printed in Malaysia by UKM CETAK Universiti Kebangsaan Malaysia 43600 UKM Bangi Selangor D.E Semua pertanyaan hendaklah diajukan kepada: Dekan Fakulti Sains Sosial dan Kemanusiaan Universiti Kebangsaan Malaysia Tel: 03-8921 4123 / 8921 5356 Faks: 03-8925 2836 E-mel: [email protected] ISSN 1823-8637 6 /Panduan Prasiswazah Sesi Akademik 2018-2019 (Ucapan Tun Abdul Razak di Konvokesyen Pertama UKM, 1973) Fakulti Sains Sosial dan Kemanusiaan / 7 Maksud Logo UKM Logo Universiti Kebangsaan Malaysia (UKM) ialah sebuah perisai yang berpetak empat. Setiap petak mengandungi gambar dan warna latar yang berlainan dengan membawa maksud tertentu. -

13952 Wednesday MAY 26, 2021 Khordad 5, 1400 Shawwal 14, 1442

WWW.TEHRANTIMES.COM I N T E R N A T I O N A L D A I L Y 8 Pages Price 50,000 Rials 1.00 EURO 4.00 AED 43rd year No.13952 Wednesday MAY 26, 2021 Khordad 5, 1400 Shawwal 14, 1442 EU welcomes extension Skocic names Iran 29 mining projects Iranian, Russian universities of surveillance deal squad for World Cup ready to go operational launch Iranistica between Iran, IAEA Page 3 qualifiers Page 3 across Iran Page 4 Encyclopedia project Page 8 Zarif holds high- level talks in Azerbaijan TEHRAN – Iranian Foreign Minister Iran presidential lineup Mohammad Javad Zarif has embarked See page 3 on a tour of the South Caucasus region amid soaring border tensions between Azerbaijan and Armenia. The chief Iranian diplomat began his tour with a visit to Baku where he met with Azerbaijani President Ilham Aliyev on Tuesday. Continued on page 3 Water projects worth over $185m inaugurated TEHRAN – Iranian Energy Minister Reza Ardakanian on Tuesday inaugurated seven major water industry projects valued at 7.81 trillion rials (about $185.9 million) through video conference in three prov- inces, IRIB reported. Put into operation in the eighth week of the ministry’s A-B-Iran program in the current Iranian calendar year (started on March 21), the said projects were inaugurated in Hormozgan, Fars, and Kurdestan provinces. Continued on page 4 “Ambushing a Rose” published in eight languages TEHRAN – Eight translations of “Ambushing a Rose”, a biography of Lieutenant-General Ali Sayyad Shirazi who served as commander of Ground Forces during the Iran–Iraq war, have recently been published. -

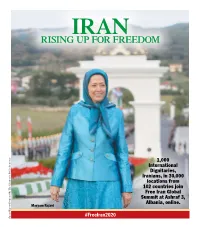

Rising up for Freedom

IRAN RISING UP FOR FREEDOM 1,000 International Dignitaries, Iranians, in 30,000 locations from 102 countries join Free Iran Global Summit at Ashraf 3, Albania, online. Maryam Rajavi #FreeIran2020 Special Report Sponsored The by Alliance Public for Awareness Iranian dissidents rally for regime change in Tehran BY BEN WOLFGANG oppressive government that has ruled Iran from both political parties participating has proven it can’t deliver for its people. tHe WasHInGtOn tImes since the Islamic Revolution of 1979. Leaders represented a who’s who list of American “The Iranian people want change, to of the NCRI, which is comprised of multiple “formers,” including former Sen. Joseph I. have democracy, finally to have human Iran’s theocracy is at the weakest point other organizations, say the council has seen Lieberman of Connecticut, former Penn- rights, to finally have economic wealth, of its four-decade history and facing un- its stature grow to the point that Iranian sylvania Gov. Tom Ridge, former Attorney no more hunger. The will of the people precedented challenges from a courageous officials can no longer deny its influence. General Michael Mukasey, retired Marine is much stronger than any oppressive citizenry hungry for freedom, Iranian dis- The NCRI has many American support- Commandant James T. Conway and others. measure of an Iranian regime,” said Martin sidents and prominent U.S. and European ers, including some with close relationships Several current U.S. officials also delivered Patzelt, a member of German Parliament. politicians said Friday at a major interna- to Mr. Trump, such as former New York remarks, including Sen. -

Tightening the Reins How Khamenei Makes Decisions

MEHDI KHALAJI TIGHTENING THE REINS HOW KHAMENEI MAKES DECISIONS MEHDI KHALAJI TIGHTENING THE REINS HOW KHAMENEI MAKES DECISIONS POLICY FOCUS 126 THE WASHINGTON INSTITUTE FOR NEAR EAST POLICY www.washingtoninstitute.org Policy Focus 126 | March 2014 The opinions expressed in this Policy Focus are those of the author and not necessarily those of The Washington Institute for Near East Policy, its Board of Trustees, or its Board of Advisors. All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including pho- tocopy, recording, or any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher. © 2014 by The Washington Institute for Near East Policy The Washington Institute for Near East Policy 1828 L Street NW, Suite 1050 Washington, DC 20036 Cover: Iran’s Supreme Leader Ayatollah Ali Khamenei holds a weapon as he speaks at the University of Tehran. (Reuters/Raheb Homavandi). Design: 1000 Colors CONTENTS Executive Summary | V 1. Introduction | 1 2. Life and Thought of the Leader | 7 3. Khamenei’s Values | 15 4. Khamenei’s Advisors | 20 5. Khamenei vs the Clergy | 27 6. Khamenei vs the President | 34 7. Khamenei vs Political Institutions | 44 8. Khamenei’s Relationship with the IRGC | 52 9. Conclusion | 61 Appendix: Profile of Hassan Rouhani | 65 About the Author | 72 1 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY EVEN UNDER ITS MOST DESPOTIC REGIMES , modern Iran has long been governed with some degree of consensus among elite factions. Leaders have conceded to or co-opted rivals when necessary to maintain their grip on power, and the current regime is no excep- tion.