The Report of the Investigation Into Matters Relating to Savile at Leeds Teaching Hospitals NHS Trust

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

NHS Leeds North Board Members Register of Interests As at May 2014

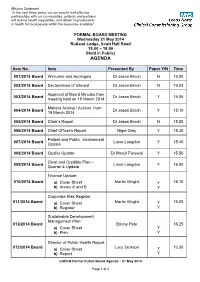

Mission Statement “In the next three years, our successful and effective partnerships with our communities, patients and partners will reduce health inequalities and deliver improvements in health for local people within the resources available” FORMAL BOARD MEETING Wednesday 21 May 2014 Rutland Lodge, Scott Hall Road 15:00 – 18:00 (Held in Public) AGENDA Item No. Item Presented By Paper Y/N Time 001/2014 Board Welcome and Apologies Dr Jason Broch N 15:00 002/2014 Board Declarations of Interest Dr Jason Broch N 15:03 Approval of Board Minutes from 003/2014 Board Dr Jason Broch Y 15:05 meeting held on 19 March 2014 Matters Arising / Actions from 004/2014 Board Dr Jason Broch Y 15:10 19 March 2014 005/2014 Board Chair’s Report Dr Jason Broch N 15:20 006/2014 Board Chief Officer’s Report Nigel Gray Y 15.30 Patient and Public Involvement 007/2014 Board Liane Langdon Y 15.40 Update 008/2014 Board Quality Update Dr Manjit Purewal Y 15.50 Clear and Credible Plan – 009/2014 Board Liane Langdon Y 16.00 Quarter 4 Update Finance Update: 010/2014 Board a) Cover Sheet Martin Wright Y 16.10 b) Annex A and B Y Corporate Risk Register 011/2014 Board a) Cover Sheet Martin Wright Y 16:20 b) Register Y Sustainable Development Management Plan: 012/2014 Board Briony Pete 16.25 a) Cover Sheet Y b) Plan Y Director of Public Health Report 013/2014 Board a) Cover Sheet Lucy Jackson Y 16.35 b) Report Y LNCCG Formal Public Board Agenda – 21 May 2014 Page 1 of 2 Leeds Better Care Fund Submission (Cover Sheet): Y a) Leeds BCF Planning Template Y 014/2014 Board b) -

BBC 4 Listings for 5 – 11 July 2008 Page 1 of 3

BBC 4 Listings for 5 – 11 July 2008 Page 1 of 3 SATURDAY 05 JULY 2008 SUN 02:40 War Stories (b0074sgs) anniversary show organised by the restaurant to celebrate its [Repeat of broadcast at 20:30 on Saturday] third year. SAT 19:00 We Dive at Dawn (b007896l) World War II drama about a mission to hunt and destroy a dangerous German battleship in the Baltic, which goes wrong MON 22:00 Overlord (b00cjznj) when the British submarine Sea Tiger runs short on fuel. A MONDAY 07 JULY 2008 British wartime drama sprinkled with newsreel footage. Typical crew member with a flair for the German language is forced to 18-year-old Tom (Brian Stirner) enters into military service disembark on an enemy-occupied Danish island. MON 19:00 World News Today (b00cgvqr) early in 1944 and goes through the rigours of training and the The latest news from around the world. tragic shock of his first battle on D-Day. SAT 20:30 War Stories (b0074sgs) Uncovering forgotten gems like Frieda and revisiting classics MON 19:30 The Sky at Night (b00ch4p6) MON 23:20 Modern Times (b0077f6h) like Ice Cold in Alex, an exploration into how war films have Rise of the Phoenix Jewish Wedding changed with the times. They were a tool of government propaganda during WW2, and while the blockbusters of the The NASA mission Phoenix has been on Mars a month and Series documenting aspects of the contemporary world. 1950s were part of national nostalgia, today they have been already there are images of the frozen ice caps, never before Michaela and Steve are planning a big Jewish wedding. -

University of Dundee the Origins of the Jimmy Savile Scandal Smith, Mark

University of Dundee The origins of the Jimmy Savile scandal Smith, Mark; Burnett, Ros Published in: International Journal of Sociology and Social Policy DOI: 10.1108/IJSSP-03-2017-0029 Publication date: 2018 Document Version Peer reviewed version Link to publication in Discovery Research Portal Citation for published version (APA): Smith, M., & Burnett, R. (2018). The origins of the Jimmy Savile scandal. International Journal of Sociology and Social Policy, 38(1/2), 26-40. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJSSP-03-2017-0029 General rights Copyright and moral rights for the publications made accessible in Discovery Research Portal are retained by the authors and/or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. • Users may download and print one copy of any publication from Discovery Research Portal for the purpose of private study or research. • You may not further distribute the material or use it for any profit-making activity or commercial gain. • You may freely distribute the URL identifying the publication in the public portal. Take down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact us providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. Download date: 25. Sep. 2021 The origins of the Jimmy Savile Scandal Dr Mark Smith, University of Edinburgh (Professor of Social Work, University of Dundee from September 2017) Dr Ros Burnett, University of Oxford Abstract Purpose The purpose of this paper is to explore the origins of the Jimmy Savile Scandal in which the former BBC entertainer was accused of a series of sexual offences after his death in 2011. -

The Leeds Teaching Hospitals

Date: 19th November 2020 Your Ref: Our Ref: Chief Medical Officer Trust Headquarters St James’s University Hospital Beckett Street Leeds LS9 7TF Direct Line: Email: PA: www.leedsth.nhs.uk Mr Kevin McLoughlin Senior Coroner West Yorkshire (Eastern) Coroner’s Office and Court 71 Northgate Wakefield WF1 3BS Dear Mr McLoughlin INQUEST TOUCHING THE DEATH OF MACLOUD NYERUKE (Deceased) I refer to your correspondence of 18th September 2020, regarding the inquest touching the death of Mr Macloud Nyeruke and the Regulation 28 Report to Prevent Future Deaths in respect of this case. I can confirm that the contents of your Regulation 28 Report have been shared with the relevant staff to enable us to provide you with a comprehensive response. In your report you highlight that your matters of concern were as follows: (1) Mr Nyeruke’s medical conditions were not made known to the Trust. In consequence, he had worked on wards where patients had infections involving multi-resistant organisms. Given his compromised immune state, this situation involved risk to both patients and Mr Nyeruke himself. In the absence of information concerning a particular staff member’s medical condition there is a risk of transmission of infections either to or from the staff member. (2) There is scant evidence as to whether Mr Nyeruke underwent appropriate training in respect of PPE such as masks before being permitted to work on a ward involving infectious diseases. The difficulties involved (where a support worker supplied by a nursing agency is only in the hospital for a brief period) are acknowledged. -

Practice Case Review 12: Jimmy Savile

All Wales Basic Safeguarding Practice Reviews Awareness Training Version 2 Practice case review 12: Jimmy Savile Sir Jimmy Savile who died in 2011 at 84 years-old was a well-known radio and television personality who came to public attention as an eccentric radio DJ in the 1960’s. At the time of his death he was respected for his charitable work having been knighted in 1990. He was closely associated with Stoke Mandeville and St James Hospitals. In the year following his death allegations were These reports looked at the various factors that being made about his sexual conduct, as these contributed to the decisions to take no action. gained publicity more individuals came forward to One report concluded that there had been an add their own experiences to a growing list. A ‘over-reliance on personal friendships between pattern of behaviour began to emerge and the Savile and some officers’. Police launched formal criminal investigation into The Health Minister Jeremy Hunt launched an allegations of historical sexual abuse. investigation into Savile’s activities within the NHS, Operation Yewtree commenced in October 2012 barrister Kate Lampard was appointed as the head and the Metropolitan Police Service concluded of this investigation which by November 2013 had that up to 450 people had alleged abuse by Savile. included thirty two NHS hospitals. A report into the findings of this criminal The findings of this investigation, published in investigation published jointly by the Police and June 2014 focussed on the following areas: The NSPCC called ‘Giving Victims a Voice’ found that abuse by Savile spanned a 50 year period and • security and access arrangements, including involved children as young as eight years-old. -

The BBC's Response to the Jimmy Savile Case

House of Commons Culture, Media and Sport Committee The BBC’s response to the Jimmy Savile case Oral and written evidence 23 October 2012 George Entwistle, Director-General, and David Jordan, Director of Editorial Policy and Standards, BBC 27 November 2012 Lord Patten, Chairman, BBC Trust, and Tim Davie, Acting Director-General, BBC Ordered by The House of Commons to be printed 23 October and 27 November 2012 HC 649-i and -ii Published on 26 February 2013 by authority of the House of Commons London: The Stationery Office Limited £10.50 The Culture, Media and Sport Committee The Culture, Media and Sport Committee is appointed by the House of Commons to examine the expenditure, administration and policy of the Department for Culture, Media and Sport and its associated public bodies. Current membership Mr John Whittingdale MP (Conservative, Maldon) (Chair) Mr Ben Bradshaw MP (Labour, Exeter) Angie Bray MP (Conservative, Ealing Central and Acton) Conor Burns MP (Conservative, Bournemouth West) Tracey Crouch MP (Conservative, Chatham and Aylesford) Philip Davies MP (Conservative, Shipley) Paul Farrelly MP (Labour, Newcastle-under-Lyme) Mr John Leech MP (Liberal Democrat, Manchester, Withington) Steve Rotheram MP (Labour, Liverpool, Walton) Jim Sheridan MP (Labour, Paisley and Renfrewshire North) Mr Gerry Sutcliffe MP (Labour, Bradford South) The following members were also members of the committee during the parliament. David Cairns MP (Labour, Inverclyde) Dr Thérèse Coffey MP (Conservative, Suffolk Coastal) Damian Collins MP (Conservative, Folkestone and Hythe) Alan Keen MP (Labour Co-operative, Feltham and Heston) Louise Mensch MP (Conservative, Corby) Mr Adrian Sanders MP (Liberal Democrat, Torbay) Mr Tom Watson MP (Labour, West Bromwich East) Powers The committee is one of the departmental select committees, the powers of which are set out in House of Commons Standing Orders, principally in SO No 152. -

The Leeds Teaching Hospitals

Date: 08/12/2016 Organisational Learning Our Ref: LTHT/ Expression of Interest Ashley Wing - Thackray Annex St James Hospital Beckett Street Leeds LS9 7TF Direct Line (0113) 2067241 www.leedsth.nhs.uk Dear Colleague, Invitations for early expressions of interest to deliver management/ leadership development for Leeds Teaching Hospitals Trust (LTHT). Organisations interested in tendering for the contract to deliver accredited management and leadership development programmes are invited, in the first instance to submit an early expression of interest. (Extensive detail is not required at this stage.) Applications should be submitted in writing to Jayne Collingwood [email protected] by 5pm on 6th January 2017. The submission should cover; Structure and duration of programmes Qualification standards Indicative pricing Quality assurance processes Resilience in delivery Learning outcomes If successful, you will be invited to give a presentation on Thursday 19th January 2017 at St James Hospital, Leeds. In relation to the programmes, it is envisaged that LTHT will be responsible for: Recruiting onto the programmes Provision of venues Providing general administrative support (not including printing or provision of training materials) 1 ORGANISATIONAL BACKGROUND Leeds Teaching Hospitals is one of the largest Trusts in the UK seeing approximately one million patients each year with an income of £970m and a staff of 12,979.5 full time equivalents. The estate is spread over five sites: Leeds General Infirmary St James’s University Hospital Chapel Allerton Hospital Seacroft Hospital Wharfedale Hospital Chair Dr Linda Pollard CBE DL Chief Executive Julian Hartley The Leeds Teaching Hospitals NHS Trust incorporating: Chapel Allerton Hospital, Leeds Cancer Centre, Leeds Children’s Hospital, Leeds Dental Institute, Leeds General Infirmary, Seacroft Hospital, St James’s University Hospital, Wharfedale Hospital. -

BBC 4 Listings for 8 – 14 October 2016 Page 1 of 4

BBC 4 Listings for 8 – 14 October 2016 Page 1 of 4 SATURDAY 08 OCTOBER 2016 SAT 01:30 Top of the Pops (b07xtbj7) The story of how we used light to reveal the cosmos begins in Peter Powell presents the weekly chart show, first broadcast on the 3rd century BC when, by trying to understand the tricks of SAT 19:00 Lost Kingdoms of South America (b01q6pzt) 20th May 1982. Includes appearances from Adam Ant, Rocky perspective, the Greek mathematician Euclid discovered that The Stone at the Centre Sharpe & The Replays, Madness, ABC, Iron Maiden, Ph.D, light travels in straight lines, a discovery that meant that if we Tight Fit, Nicole and Patrice Rushen. Also features a dance could change its path we could change how we see the world. In Deep in the Bolivian Andes at the height of 13,000ft stands performance from Zoo. Renaissance Italy 2,000 years later, Galileo Galilei did just that Tiwanaku, the awe-inspiring ruins of a monolithic temple city. by using the lenses of his simple telescope to reveal our true Built by a civilisation who dominated a vast swathe of South place in the cosmos. America, it was abandoned 1,000 years ago. For centuries it has SAT 02:05 It's Only Rock 'n' Roll: Rock 'n' Roll at the BBC been a mystery - how did a civilisation flourish at such an (b063m6wy) With each new insight into the nature of light came a fresh altitude and why did it vanish? [Repeat of broadcast at 22:30 today] understanding of the cosmos. -

Blue Plaques Erected Since the Publication of This Book

Leeds Civic Trust Blue Plaques No Title Location Unveiler Date Sponsor 1 Burley Bar Stone Inside main entrance of Leeds Lord Marshall of Leeds, President of Leeds Civic 27 Nov ‘87 Leeds & Holbeck Building Society Building Society, The Headrow Trust, former Leader of Leeds City Council Leeds 1 2 Louis Le Prince British Waterways, Leeds Mr. William Le Prince Huettle, great-grandson 13 Oct ‘88 British Waterways Board Bridge, Lower Briggate, Leeds of Louis Le Prince (1st Plaque) 1 3 Louis Le Prince BBC Studios, Woodhouse Sir Richard Attenborough, Actor, Broadcaster 14 Oct ‘88 British Broadcasting Corporation Lane, Leeds 2 and Film Director (2nd Plaque) 4 Temple Mill Marshall Street, Leeds 11 Mr Bruce Taylor, Managing Director of Kay’s 14 Feb ‘89 Kay & Company Ltd 5 18 Park Place 18 Park Place, Leeds 1 Sir Christopher Benson, Chairman, MEPC plc 24 Feb ‘89 MEPC plc 6 The Victoria Hotel Great George Street, Leeds 1 Mr John Power MBE, Deputy Lord Lieutenant of 25 Apr ‘89 Joshua Tetley & Sons Ltd West Yorkshire 7 The Assembly Rooms Crown Street, Leeds 2 Mr Bettison (Senior) 27 Apr ‘89 Mr Bruce Bettison, then Owner of Waterloo Antiques 8 Kemplay’s Academy Nash’s Tudor Fish Restaurant, Mr. Lawrence Bellhouse, Proprietor, Nash’s May ‘89 Lawrence Bellhouse, Proprietor, Nash’s off New Briggate, Leeds 1 Tudor Fish Restaurant Tudor Fish Restaurant 9 Brodrick’s Buildings Cookridge Street, Leeds 2 Mr John M. Quinlan, Director, Trinity Services 20 Jul ‘89 Trinity Services (Developers) 10 The West Bar Bond Street Centre, Boar Councillor J.L. Carter, Lord Mayor of Leeds 19 Sept ‘89 Bond Street Shopping Centre Merchants’ Lane, Leeds 1 Association Page 1 of 14 No Title Location Unveiler Date Sponsor 11 Park Square 45 Park Square, Leeds 1 Mr. -

Choosing Your Hospital

Choosing your hospital Leeds Primary Care Trust For most medical conditions, you can now choose where and when to have your treatment. This booklet explains more about choosing your hospital. You will also find information about the hospitals you can choose from. Second edition December 2006 Contents What is patient choice? 1 Making your choice 2 How to use this booklet 3 Where can I have my treatment? 4 Your hospitals A to Z 7 Your questions answered 30 How to book your appointment 32 What do the specialty names mean? 33 What does the healthcare jargon mean? 35 Where can I find more information and support? 37 How do your hospitals score? 38 Hospital score table 42 What is patient choice? If you and your GP decide that you need to see a specialist for more treatment, you can now choose where and when to have your treatment from a list of hospitals or clinics. Why has patient choice been introduced? Research has shown that patients want to be more involved in making decisions and choosing their healthcare. Most of the patients who are offered a choice of hospital consider the experience to be positive and valuable. The NHS is changing to give you more choice and flexibility in how you are treated. Your choices Your local choices are included in this booklet. If you do not want to receive your treatment at a local hospital, your GP will be able to tell you about your choices of other hospitals across England. As well as the hospitals listed in this booklet, your GP may be able to suggest community-based services, such as GPs with Special Interests or community clinics. -

Themes and Lessons Learnt from NHS Investigations Into Matters Relating to Jimmy Savile

Themes and lessons learnt from NHS investigations into matters relating to Jimmy Savile Independent report for the Secretary of State for Health February 2015 Authors: Kate Lampard Ed Marsden Themes and lessons learnt from NHS investigations into matters relating to Jimmy Savile Independent report for the Secretary of State for Health February 2015 Authors: Kate Lampard Ed Marsden Contents 1. Foreword 4 2. Introduction 6 3. Terms of reference 9 4. Executive summary and recommendations 10 5. Methodology 26 6. Findings of the NHS investigations 32 7. Historical background 36 8. Our understanding of Savile’s behaviour and the risks faced by NHS hospitals today 41 9. Findings, comment and recommendations on identified issues 47 10. Security and access arrangements 48 11. Role and management of volunteers 54 12. Safeguarding 67 13. Raising complaints and concerns 101 14. Fundraising and charity governance 110 15. Observance of due process and good governance 119 16. Ensuring compliance with our recommendations 120 17. Conclusions 121 Appendices Appendix A Biographies 123 Appendix B Letters from Right Honourable Jeremy Hunt MP, Secretary of State for Health, to Kate Lampard 124 Appendix C List of interviewees 131 Appendix D Kate Lampard’s letter to all NHS trusts, foundation trusts and clinical commissioning groups (CCG) clinical leaders 136 2 Appendix E List of organisations or individuals who responded to our call for evidence 138 Appendix F Documents reviewed 141 Appendix G List of trusts visited as part of the work 146 Appendix H List of investigations into allegations relating to Jimmy Savile 147 Appendix J Discussion event attendees 149 3 1. -

The Leeds Teaching Hospitals Nhs Trust

THE LEEDS TEACHING HOSPITALS NHS TRUST DEPARTMENT OF RADIOLOGY JOB DESCRIPTION CONSULTANT RADIOLOGIST 1. BACKGROUND Leeds Teaching Hospitals is one the largest teaching hospital trusts in Europe, with access to leading clinical expertise and medical technology. We care for people from all over the country as well as the 780,000 residents of Leeds itself. The Trust has a budget of £1.1 billion. Our 20,000 staff ensure that every year we see and treat over 1,500,000 people in our 2,000 beds or out-patient settings, comprising 100,000 day cases, 125,000 in-patients, 260,000 A&E visits and 1,050,000 out-patient appointments. We operate from 7 hospitals on 5 sites – all linked by the same vision, philosophy and culture to be the best for specialist and integrated care. Our vision is based on The Leeds Way, which is a clear statement of who we are and what we believe, founded on values of working that were put forward by our own staff. Our values are to be: Patient-centred Fair Collaborative Accountable Empowered We believe that by being true to these values, we will consistently achieve and continuously improve our results in relation to our goals, which are to be: 1. The best for patient safety, quality and experience 2. The best place to work 3. A centre of excellence for specialist services, education, research and innovation 4. Hospitals that offer seamless, integrated care 5. Financially sustainable Leeds Teaching Hospitals NHS Trust is part of the West Yorkshire Association of Acute Trusts (WYAAT), a collaborative of the NHS hospital trusts from across West Yorkshire and Harrogate working together to provide the best possible care for our patients.