CENTRAL EUROPE REVISITED (Part 2)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

3 Meeting of the EU Network on Public Administration And

3rd meeting of the EU network on Public administration and governance 3rd meeting of the EU network on Public administration and governance INFORMATION FOR PARTICIPANTS 10-11th November 2016 One Stop Shop Tomášikova 46, 831 04 Bratislava 3 Slovakia 3rd meeting of the EU network on Public administration and governance AIM OF THE MEETING rd Focus of the „3 meeting of the EU network on Public administration and governance“ is process optimalization and improving of service delivery to the citizens. The idea of meeting is to enable sharing of experiences and approaches to analyze and hopefully suggest a new design (or redesign) of selected serviceses provided at the Client Centre, using the Vanguard Method. SLOVAK CONTEXT Ministry of Interior in cooperation with various partners currently realizes activities of the ESO reform (Slovak equivalent of Effective, Reliable and Open state administration). Since 1989, it is the biggest reform of Slovak state administration with an ambition to provide efficient, quality, transparent and accessible public services to their citizens. Yet, the integration of local state administration has been completed and accompanied by opening of 49 Public Administration Client Centres. Implementing measures regarding optimalization of performance of state administration, processes and structures of central authorities are carried out by „Optimalization project“ which is going to be submitted in the near future and is part of operational programme Effective Public Administration 2016 – 2020. The aim of rationalisation of processes is to simplify public services in relation to life situations of citizens, enterpreneurs, NGOs and public administration. 3rd meeting of the EU network on Public administration and governance EVENT DATES AND VENUE The “3rd meeting of the EU network on Public Administration and governance” is organized by the Ministry of Interior of the Slovak Republic. -

Regiăłn Bratislava GB.Indd

Bratislava Region Región Bratislava GB.indd 1 14.11.2008 14:01:59 Výtažková azurováVýtažková purpurováVýtažková žlutáVýtažková ìerná LittleBigCountry Región Bratislava GB.indd 2 14.11.2008 14:02:02 Výtažková azurováVýtažková purpurováVýtažková žlutáVýtažková ìerná The Bratislava Region lies in West and Southwest Slovakia, and contains the southern part of the Little Carpathian Mountains, the Záhorie Lowlands and the Danube Lowlands. Its neighbours are the Trnava Region in the north and east, Hungary in the south, and Austria and the Czech Republic in the west. The Slovak capital Bratislava is the natural centre of the region in terms of political, economic and social life. Región Bratislava GB.indd 3 14.11.2008 14:02:12 Výtažková azurováVýtažková purpurováVýtažková žlutáVýtažková ìerná Bratislava With a favourable geographical position, the Bratislava Region services focus on the local history, culture and traditions, is an important venue for tourism which has become a crucial catering, shopping and congress tourism. The area along part of the local economy. Although relatively modest in size, the river Danube is traditionally associated with water, and the region boasts beautiful and diverse nature and excellent the place is ideal for summer holidays, water tourism and infrastructure, which makes it a place offering ample opportunity fi shing. for the growth of tourism. In particular, Bratislava‘s tourism Región Bratislava GB.indd 4 14.11.2008 14:02:17 Výtažková azurováVýtažková purpurováVýtažková žlutáVýtažková ìerná Bratislava Old Town SNP Bridge The Záhorie region is especially known for its natural beauties, historical monuments, and ample opportunities for water sports and relaxation. The Little Carpathian Mountains have a considerable reputation for wine growing and rich traditions of folk art. -

Music Tour of Central Europe

MUSIC TOUR OF CENTRAL EUROPE DAY 1: Arrival in Prague Transfer from Prague airport to the hotel. Check into your hotel and overnight in Prague. DAY 2: Prague Prague is literally a golden city thanks to its rich history and culture of arts. The morning tour will show you the main sites of Prague like the Prague Castle district. This tour begins at Loretto Square in the Castle's district. From this square we will enjoy a walking tour to the Archbishop's Palace in renaissance style with a rococo facade and continues to the Hradčany hall, the entrance to the Castle. And walk through the Golden Lane. After having visited this we will continue through Karlova street. This street leads to the Square of the Knights of the Cross by Charles Bridge. After the tour you will have some free time for lunch and discovering the city on your own. In the afternoon you will meet the tour leader again to transfer you to the church or alternative venue, where the concert will take place. Overnight in Prague. Day 3: Prague Today you will take you on a full-day sightseeing tour of Prague, one of the most interesting and beautiful cities in Central Europe. Your walking tour will include a visit to Wensceslas Square, the medieval Charles Bridge adorned with its many Baroque figures, St. Nicholas’ Church and Prague Castle, which was built in the 9th Century. On entering the castle you will see St. Vitus’ Cathedral and the 16th Century Golden Lane. This was once the merchant’s quarter, consisting of small town houses built into the castle walls. -

Of the Slovak Republic

Coin details Denomination: €25 Composition: 999 silver Weight: 31.10 g (1 oz) Diameter: 40 mm Edge: relief elements of ‘Čičmany village’ ornamentation Issuing volume: limited to a maximum of 11 000 (including brilliant uncirculated and proof quality) Designer: Pavel Károly Engraver: Dalibor Schmidt Producer: Mincovňa Kremnica The obverse of the coin depicts the Czechoslovak flag Bratislava Castle with the flags of Slovakia and the European Union transforming into the Slovak flag in a U-shape composi- tion, symbolising the establishment of the Slovak Republic. Above the Slovak flag is an image of Bratislava castle. Two symbols of Czechoslovakia are depicted in the lower part of the design, linking the ends of the two flags: Charles Bridge in Prague and Kriváň Peak in Slovakia’s High Tat- ra Mountains. The coin’s denomination and currency ‘25 EURO’ appear in two lines between the vertical flags. At the lower right side, in semi-circle, is the name of the issu- ing country ‘SLOVENSKO’ and the year of issuance ‘2018’. Slovakia adopted the euro on 1 January 2009 The reverse design symbolises Slovakia’s entry into the Eu- ropean Union and euro area by showing a stylised portal Joining the European Union in 2004 was an important arching over both a map of Slovakia and a euro symbol milestone in the short history of independent Slovakia. EU surrounded by EU stars (some covered by the map). From membership has brought new possibilities to the country, the left edge to the bottom, in semi-circle, is the inscrip- raised its credibility and helped it to achieve a respected tion ‘25 ROKOV SLOVENSKEJ REPUBLIKY’ (25 years of the position. -

About Bratislava

SLOVAKIA – PART OF EUROPE WORTH SEEING P. O. Box 35 Branch office Bratislava 974 05 Banská Bystrica 5 P. O. Box 76 Slovak Republic 850 05 Bratislava 55 Tel.: 00421/48/413 61 46-8 Slovak Republic Fax: 00421/48/413 61 49 Tel.: 00421/2/5342 1023-5 E-mail: [email protected] Tel./Fax: 00421/2/5342 1021 http://www.slovakiatourism.sk E-mail: [email protected] Metropolis on the Danube River Although Bratislava belongs among the youngest ca- pital cities of the world, its history dates back to the Old PL Ages. During the course of the centuries it changed its name several times: from the German Pressburg, Latin Possonium, Hungarian Pozsony, to the Slovak folk ver- sion Prešporok. CZ UA The city lies at the foot of the Small Carpathian SK Mountain Range and is inextricably linked to the Bratislava • Danube River, the second longest European river. This A European waterway was also at the birth of the first sett- H lement in Bratislava and the river served as a thorough- St. Elisabeth Church, St. Martin’s Dome fare for nations, as well as for cultural trends. Suitable known as the Blue Church geographic position was a pre-determining factor for Grassalkovich palace Bratislava’s famous past and present. (President’s residence) Slovak National Museum In the meantime the metropolis on the Danube River became a modern city, attracting visitors with a multitu- From left to right: •Grassalkovich Palace residence of the President of the Slovak Bratislava Castle Old Town Hall de of cultural offering, congress and shopping centres, Republic as well as international standard hotels, together with a • Slovak National Theatre diverse culinary offer. -

MAPA A2 BA.Indd

1 234567 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 A and 8 queens were crowned here. The cathedral eclectic new building was built between 1913 PAMÄTIHODNOSTI fontána stojí pred divadlom od roku 1888 a patrí Nationalmuseums und die Repräsentationsräume medzi najkrajšie bratislavské fontány. tower rises to a height of 85 metres and is and 1919, and provided the town with premises der staatlichen Institutionen besichtigt werden. Hrad 1 F1 MAPA KRAJA/MAP OF THE REGION/ topped off by a gold-plated replica of the royal for holding various social events and concerts. At Národná kultúrna pamiatka, mohutná Reduta 12 G4 Martins-Dom 2 F2 LANDKARTE DES KREISES Hungarian crown (1 m high and weighing 300 present, it is home to the Slovak Philharmonic. obdĺžniková bloková stavba so štyrmi Na mieste bývalej erárnej sýpky postavili Nationales Kulturdenkmal; gotische Kirche mit kg) on a gilded cushion (2x2 m in size). 13 Informačné centrum/Information/Information nárožnými vežami stojí na strategickom mieste v rokoch 1913 – 1919 eklektickú novostavbu, J. A. Komenský University G5 mehreren Kapellen, geweiht im Jahre 1452. osídlenom už v dobe keltskej a veľkomoravskej. čím mesto získalo priestory na usporiadanie Old Town Hall 3 F3 This building, originally built as a granary In den Jahren 1563-1830 wurden hier 11 Kostol/Church/Kirche Architektúru hradu najviac poznačili dostavby rozličných spoločenských udalostí a koncertov. A complex of various buildings originating from exchange, in 1937 became the seat of the ungarische Könige und 8 königliche Gemahlinnen Hrad, kaštieľ, zrúcanina hradu/Castle, a prestavby v období gotiky, renesancie Dnes je sídlom Slovenskej filharmónie different architectural periods. -

29. MAY 2011 from Vienna the Trip Went on to Bratislava in Slovakia

BRATISLAVA 26. – 29. MAY 2011 From Vienna the trip went on to Bratislava in Slovakia. The location of Slovakia in Europa Flag Coat of arms Slovakia, officially The Slovak Republic, has about 5,4 million inhabitants, and an area of about 49 000 km². Slovakia is relatively young as an independent state, and was independent as lat as in 1993 when Czechoslovakia was dissolved. During the history the area has been part of more powerful states, such as Great Moravia, Kingdom of Hungary and Austria-Hungary. Since it got its independence, Slovakia has been a stable democracy with a big economic growth. The country became member of EU and NATO in 2004, and in 2009 Slovakia went into the Euro-zone. The location of Bratislava in Slovakia Flag Coat of arms Bratislava (Pressburg/Pozsony) lies by an important strategic spot, the place has been inhabited in many thousand years and was fortified by among others the Romans. It got city rights in 1291. The city was a part of Hungary from 907 to 1918. It was the capital of The Kingdom of Hungary from 1536 to 1784, and a part of Austria-Hungary from 1526 to the end of WWI. It was Hungarian coronation city between 1563 and 1830, and seat of the Hungarian Parliament from 1542 to 1848. In 1919 the city became a part of Czechoslovakia, and the present name was introduced. Between 1939 and 1945 it was capital in the state Slovakia, which was founded on German initiative in 1938. Then it again became Czechoslovakian, before it again became capital in Slovakia in 1993. -

Scenic Eastern Europe

COST SAVER 10D7N SCENIC EASTERN EUROPE (Validity: Apr - Oct 2017) TOUR CODE: EEBUDS Unearth the vivid landscapes of cities steeped in history on this fascinating tour of eastern Europe. 123RF DANUBE RIVER, BUDAPEST PHOTOS: 18 Southern & Eastern Europe | EU Holidays HIGHLIGHTS HUNGARY BUDAPEST • Heroes’ Square • Matthias Church • Fisherman’s Bastion • Gellért Hill • Vaci Utca SLOVAKIA BRATISLAVA • Old Town • Bratislava Castle • Grassalkovich Palace • Primate’s Palace AUSTRIA VIENNA • Schönbrunn Palace • St. Stephen’s Cathedral • Ringstrasse • Hofburg Imperial Palace • State Opera House CZECH REPUBLIC ČESKÝ KRUMLOV • Český Krumlov Castle DAY 1 You may wish to embark on an optional • Old Town SINGAPORE → BUDAPEST Danube river cruise that covers the most KARLOVY VARY Meals on Board fascinating sights in Budapest, or visit one of • Spa town Assemble at Changi airport and take-off to the beautiful artistic village, Szentendre. PILSEN the capital city of Hungary, Budapest. • Beer Factory DAY 4 PRAGUE DAY 2 BUDAPEST → BRATISLAVA • Prague Castle BUDAPEST Breakfast, Dinner – Western Fare • St. Vitus Cathedral Dinner Journey to Bratislava, the political, • Old Royal Palace Get to know the true culture of Budapest, economic and cultural centre of Slovakia, • Wenceslas Square also known as the ‘City of Baths’ through and along the way, you may wish to make • Astronomical Clock a guided city tour that will help you pack an optional pit stop at the Designer Outlet • Charles Bridge as much as possible into your exploration Pandorf near Vienna for a spot of shopping. of the city. The first stop of the tour is the Set off on a sightseeing tour of the city’s renowned Matthias Church, one of the main attractions – visit the Old Town for DELICACIES oldest buildings in Budapest with over a view of some of the oldest historical 700 years of history and frescoes done buildings, the unique Bratislava Castle that Meal Plan by famous Hungarian painters. -

Bratislava.Falkensteiner.Com 9

DEUTSCH · ENGLISH Meetings & Events bratislava.falkensteiner.com 9 TSCHECHIEN CZECH REPUBLIC SLOWAKEI SLOVAKIA 15 5/6 8 ÖSTERREICH AUSTRIA 13 7 14 2 12 11 1 ITALIEN KROATIEN ITALY 4 CROATIA 10 3 16 SERBIEN SERBIA 1. Schlosshotel Velden FFFFF (Österreich / Austria) · 2. Balance Resort Stegersbach FFFFF (Österreich / Austria) · 3. Hotel & Spa Iadera FFFFF (Kroatien / Croatia) · 4. Hotel & Spa Jesolo FFFFF (Italien / Italy) · 5. Hotel Wien Margareten FFFFS (Öster reich / Austria) · 6. Hotel Am Schottenfeld FFFF (Österreich / Austria) · 7. Hotel & Asia Spa Leoben FFFF (Österreich / Austria) · 8. Hotel Bratislava FFFF (Slowakei / Slovakia) · 9. Hotel Maria Prag FFFF (Tschechien / Czech Republic) · 10. Hotel Belgrade FFFFS (Serbien / Serbia) · 11. Hotel & Spa Carinzia FFFFS (Österreich / Austria) · 12. Hotel Sonnenalpe FFFF (Österreich / Austria) · 13. Hotel Schladming FFFFS (Österreich / Austria) · 14. Therme & Golf Hotel Bad Waltersdorf FFFFS (Österreich / Austria) · 15. Hotel & Spa Bad Leonfelden FFFF (Österreich / Austria) · 16. Club Funimation Borik FFFF (Kroatien / Croatia) 2 WELCOME HOME! FOR EXPERT PLANNERS PERSÖNLICHER „WELCOME HOME! HOST“ PERSONAL “WELCOME HOME! HOST” Beste Betreuung on the Spot – vor Ihnen beim Kommen, nach The best service on the spot – available before you arrive and Ihnen beim Gehen – Ihr persönlicher Planner Experts Ansprech- after you leave. Your own personal expert planner is via hotline partner ist via Hotline jederzeit für Sie erreichbar. always at your disposal. MEET & LIFE BALANCE MEET & LIFE BALANCE Erfolgreicher -

Download This PDF File

127–135 THE SYMBOLIC SIGNIFICANCE OF THE POSITION OF THE HUNGARIAN PRESIDENT IN A CENTRAL EUROPEAN CONTEXT Ivan Halász* Abstract: Since the birth of modern republics, the post of the president of the republic has had important symbolic content. It is a powerful symbol of republicanism. The presidents of most republics have inherited many characteristics of previous dynastic rulers, as their partly similar functions – representing the state in and outside the country, symbolising the unity of the nation and in periods of crisis, guaranteeing the conti- nuity of state power. The paper is concerning on the Hungarian constitutional development in the 20th century and especially after 2011. Symbolism of the new Fundamental Law of Hungary is very strong and the position of president is central in this process. Keywords: head of state, nation, republic, symbols, traditions The monarchy was a dominant form of state in Europe before the end of the 18th century. But the situation was similar in the long 19th century as well, despite of the Great French Revolution. The republican tradition of post-revolutionary France, Spain and Portugal was not continuous. The history of modern republics in Central Europe has started only after the First World War, when the Austrian, Czechoslovak and Polish Republics were declared. Only Hungary preserved the kingdom in the interwar period. Maybe it is a reason for the less expressive tradition of republicanism in modern Hungary. Since the birth of modern republics, the post of the president of the republic has had important symbolic content. It is a powerful symbol of republicanism, as the very existence of the presidency indicates that the country is not a monarchy but a republic. -

Bratislava CARD City & Region Guided Tours and Excursions Bratislava Official Bratislava App 2020 CARD 2021

SK EN DE Connect to free wifi VisitBratislava BRATISLAVA TOURIST BOARD your partner and welcome point to the city Tourist information Bratislava CARD City & Region Guided tours and excursions Bratislava Official Bratislava App 2020 CARD 2021 Free use of public transport Free admission to museums & galleries Free guided walking tour Implemented with the financial support of the Ministry of Transport and Construction of the Slovak Republic. Other discounts up to 50 % Bratislava Tourist Board Tourist Information Centre Primaciálne nám. 1 Klobučnícka 2 P. O. BOX 349 SK-811 01 Bratislava 810 00 Bratislava Tel.: +421 2 16 186 [email protected] Tel.: +421 2 5935 6651 www.visitbratislava.com [email protected] III / 2020 www.visitbratislava.com/bc SK AKO AKTIVOVAŤ KARTU Karta je neprenosná a môže ju využívať len jej držiiteľ. Ihneď po jej kúpe vyplňte zadnú stranu karty guľôčkovým perom. Do príslušného popisového poľa uveďte čitateľne paličkovým písmom svoje meno a priezvisko 1 , ako aj dátum v tvare deň, mesiac, rok 2 a hodinu jej prvého využitia 3 podľa priloženého vzoru. Karty s nevyplnenými alebo dodatočne opravovanými údajmi sú neplatné. Stratenú | odcudzenú | poškodenú kartu nie je možné nahradiť. EN HOW TO ACTIVATE THE CARD The card is non-transferable and cannot be used by another person. Immediately after purchase fill out the reverse side of the card with a ball- point pen. Fill out the blank fields clearly in block capitals with your name and surname 1 , date in the following order: day, month, year 2 and hour of the first use 3 according to the example provided. -

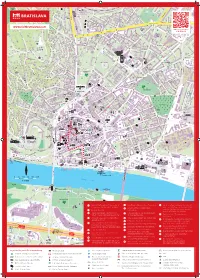

Mapa A3 Print 2.Pdf

www.visitbratislava.com Official applications of Bratislava 6. Kostol a kláštor Františkánov | Franciscan church 17. Kostol Trinitárov | Trinitarian church | Trinitarierkirche 30. Gotická veža z Františkánskeho kostola v Sade J. Kráľa and monastery | Franziskanerkirche und Kloster Gothic tower of the Franciscan Church in Sad J. Kráľa 18. Kostol sv. Ladislava | St. Ladislavs'church (Janko Kráľ Park) | Gotischer Turm der Franziskaner- 7. Academia istropolitana Ladislauskirche kirche in der Parkanlage Sad Janka Kráľa 8. Kostol a kláštor Klarisiek | Church and convent 19. Veľký evanjelický kostol | Great Lutheran Church 31. Korunovačná trasa | The coronation route of the St. Clare nuns | Klarissenkirche und Kloster Grosse evangelische Kirche Krönungsweg 9. Dom u dobrého pastiera | Good shepherd House 22. Mirbachov palác | Mirbach Palace | Mirbach Palais 32. Kostol Nanebovzatia Panny Márie (Blumentálsky kostol) Haus zum Guten Hirten 23. Pálfyho palác | Pálffy Palace | Pálffy Palais Church of the Assumption (Blumenthal Church) 11. Slovenské národné divadlo - historická budova Kirche Mariä Himmelfahrt (Blumenthal-Kirche) 24. Esterházyho palác | Esterházy Palace | Esterházy Palais Slovak national theatre – historical building 33. Národná banka Slovenska | National Bank Slowakisches Nationaltheater- historisches Gebäude 25. Stará tržnica | Old Market Hall | Alte Markthalle of Slovakia | Slowakische Nationalbank 12. Reduta | Reduta | Redoute 26. Slovenské národné divadlo - nová budova Slovak national theatre – new building 34. Slovenský rozhlas