TABLE of CONTENTS Acknowledgements

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Chapter IX: Ukrainian Musical Folklore Discography As a Preserving Factor

Art Spiritual Dimensions of Ukrainian Diaspora: Collective Scientific Monograph DOI 10.36074/art-sdoud.2020.chapter-9 Nataliia Fedorniak UKRAINIAN MUSICAL FOLKLORE DISCOGRAPHY AS A PRESERVING FACTOR IN UKRAINIAN DIASPORA NATIONAL SPIRITUAL EXPERIENCE ABSTRACT: The presented material studies one of the important forms of transmission of the musical folklore tradition of Ukrainians in the United States and Canada during the XX – the beginning of the XXI centuries – sound recording, which is a component of the national spiritual experience of emigrants. Founded in the 1920s, the recording industry has been actively developed and has become a form of preservation and promotion of the traditional musical culture of Ukrainians in North America. Sound recordings created an opportunity to determine the features of its main genres, the evolution of forms, that are typical for each historical period of Ukrainians’ sedimentation on the American continent, as well as to understand the specifics of the repertoire, instruments and styles of performance. Leading record companies in the United States have recorded authentic Ukrainian folklore reconstructed on their territory by rural musicians and choirs. Arranged folklore material is represented by choral and bandura recordings, to which are added a large number of records, cassettes, CDs of vocal-instrumental pop groups and soloists, where significantly and stylistically diversely recorded secondary Ukrainian folklore (folklorism). INTRODUCTION. The social and political situation in Ukraine (starting from the XIX century) caused four emigration waves of Ukrainians and led to the emergence of a new cultural phenomenon – the art and folklore of Ukrainian emigration, i.e. diaspora culture. Having found themselves in difficult ambiguous conditions, where there was no favorable living environment, Ukrainian musical folklore began to lose its original identity and underwent assimilation processes. -

TOBACCO WORLD RETAIL PRICES (Ovor 5,000 Retail PI-ICM)

THE CIGAR AND THE TOBACCO WORLD THE POPULAR JOURNAL TOBACCO OVER 40 YEARS OF TRADE USEFULNESS WORLD The Subscription includes : TOBACCO WORLD RETAIL PRICES (Ovor 5,000 Retail PI-ICM). RETAIL PRICES THE TOBACCO WORLD ANNUAL (Containing a word of Trad* Brand*—with Nam* and Addrau In each cms*). Membership of: TOBACCO WORLD SERVICE JUNE 1935 (With Pott Fnta raplUa In all Trad* difficult!**). The Cigar & Tobacco World HIYWOOO A COMPANY LTD. Dmrr How*, Kin—U 3tr*M, Ontry Una, London, W.C1 trantfc OACM f Baadmur. •trmlnfhtn, Uteanar. ToWfTHM i OffUlfrunt, Phono, LonAon. •Phono I TomaU far M1J Published by THE CIGAR & TOBACCO WORLD HEYWOOD & CO., LTD. DRURY HOUSE, RUSSELL STREET, DRURY LANE, LONDON, W.C.2 Branch Offices: MANCHESTER, BIRMINGHAM, LEICESTER Talagrarm : "Organigram. Phono, London." Phono : Tampla Bar MZJ '' Inar) "TOBACCO WORLD" RETAIL PRICES 1935 Authorised retail prices of Tobaccos, Cigarettes, Fancy Goods, and Tobacconists' Sundries. ABDULLA & Co., Ltd. (\BDULD^ 173 New Bond Street, W.l. Telephone; Bishopsgnte 4815, Authorised Current Retail Prices. Turkish Cigarettes. Price per Box of 100 50 25 20 10 No. 5 14/6 7/4 3/8 — 1/6 No. 5 .. .. Rose Tipped .. 28/9 14/6 7/3 — 3/- No. 11 11/8 5/11 3/- - 1/3 No. II .. .. Gold Tipped .. 13/S 6/9 3/5 - No. 21 10/8 5/5 2/9 — 1/1 Turkish Coronet No. 1 7/6 3/9 1/10J 1/6 9d. No. "X" — 3/- 1/6 — — '.i^Sr*** •* "~)" "Salisbury" — 2/6 — 1/- 6d. Egyptian Cigarettes. No. 14 Special 12/5 6/3 3/2 — — No. -

Pathways to Resilience: Formal Service and Informal Support Use Patterns Among Youth in Challenging Social Ecologies

Pathways to Resilience: Formal Service and Informal Support Use Patterns among Youth in Challenging Social Ecologies IDRC Project Number: 104518 Final technical report February 2015 Country/Region: China, Colombia, South Africa Prepared by: Tian Guoxiu, Faculty of Politics and Law Capital Normal University Beijing, China [email protected] Alexandra Restrepo Henao, National School of Public Health Universidad de Anioquia Medellín, Colombia [email protected] Linda Theron, Optentia Research Focus Area Faculty of Humanities North-West University, Hendrik van Eck Boulevard, Vanderbijlpark, South Africa [email protected] Madine VanderPlaat Dept. of Sociology & Criminology Saint Mary’s University Halifax, Canada This report is presented as received from project recipient(s). It comprises the reports by the P.I.s from China, Colombia, and South Africa, some of which have been edited for clarity. The report also includes content from students involved in the project, which appears with their consent. The authors gratefully acknowledge the editorial support of Aliya Jamal (RA at the Resilience Research Centre). It has not been subjected to peer review or other review processes. Keywords: resilience, youth, China, Colombia, South Africa, community advisory panel, social ecology, formal service ecology, formal supports, informal supports, mixed methods Table of Contents Tribute to Luis Fernando Duque .................................................................................................. 1! 1! Research problem .................................................................................................................. -

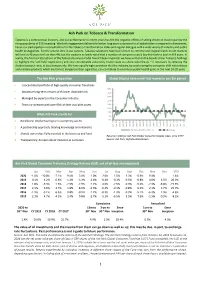

Ash Park on Tobacco & Transformation

Ash Park on Tobacco & Transformation Tobacco is a controversial industry, and our performance in recent years has felt the negative effects of selling driven at least in part by the rising popularity of ESG investing. We think engagement delivers far better long-term outcomes for all stakeholders compared to divestment, hence our participation in consultations for the Tobacco Transformation Index and regular dialogue with a wide variety of industry and public health protagonists. For the second time in our careers, Tobacco valuations have been driven to extreme and illogical levels: credit markets will lend at 40 years for less than 4%, but the equity is so lowly-rated that a number of companies could buy themselves back in 8-9 years. In reality, the financial attractions of the Tobacco business model haven’t been impaired; we have written to the boards of our Tobacco holdings to highlight the ‘self-help’ opportunity and very considerable value they could create via share repurchases – if necessary by rebasing the dividend payout ratio, at least temporarily. We have equally high conviction that the industry, by accelerating the consumer shift into tobacco and nicotine products which are far less dangerous than cigarettes, can contribute to enormous public health gains in the next 10-20 years. The Ash Park proposition Global Staples have never lost money in any 5yr period • Concentrated portfolio of high-quality consumer franchises 40% • Attractive long-term returns with lower downside risk 35% 30% • Managed by experts in the Consumer industry 25% • Team co-invested with over 90% of their available assets 20% 15% 10% What Ash Park stands for 5% 1. -

Folklore and the Construction of National Identity in Nineteenth Century Russian Literature

Folklore and the Construction of National Identity in Nineteenth Century Russian Literature Jessika Aguilar Submitted in partial fulfillment of the Requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy In the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences Columbia University 2016 © 2016 Jessika Aguilar All rights reserved Table of Contents 1. Introduction……………………………………………………………………………..…..1 2. Alexander Pushkin: Folklore without the Folk……………………………….20 3. Nikolai Gogol: Folklore and the Fragmentation of Authorship……….54 4. Vladimir Dahl: The Folk Speak………………………………………………..........84 5. Conclusion……………………………………………………………………………........116 6. Bibliography………………………………………………………………………………122 i Introduction In his “Literary Reveries” of 1834 Vissarion Belinsky proclaimed, “we have no literature” (Belinskii PSS I:22). Belinsky was in good company with his assessment. Such sentiments are rife in the critical essays and articles of the first third of the nineteenth century. A decade earlier, Aleksandr Bestuzhev had declared that, “we have a criticism but no literature” (Leighton, Romantic Criticism 67). Several years before that, Pyotr Vyazemsky voiced a similar opinion in his article on Pushkin’s Captive of the Caucasus : “A Russian language exists, but a literature, the worthy expression of a mighty and virile people, does not yet exist!” (Leighton, Romantic Criticism 48). These histrionic claims are evidence of Russian intellectuals’ growing apprehension that there was nothing Russian about the literature produced in Russia. There was a prevailing belief that -

This Content Downloaded from 132.174.254.159 on Tue, 08 Dec

This content downloaded from 132.174.254.159 on Tue, 08 Dec 2015 11:09:27 UTC All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions LETTERS FROM HEAVEN: POPULAR RELIGION IN RUSSIA AND UKRAINE This content downloaded from 132.174.254.159 on Tue, 08 Dec 2015 11:09:27 UTC All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions This page intentionally left blank This content downloaded from 132.174.254.159 on Tue, 08 Dec 2015 11:09:27 UTC All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions Edited by JOHNPAUL HIMKA and ANDRIY ZAYARNYUK Letters from Heaven Popular Religion in Russia and Ukraine UNIVERSITY OF TORONTO PRESS Toronto Buffalo London This content downloaded from 132.174.254.159 on Tue, 08 Dec 2015 11:09:27 UTC All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions www.utppublishing.com © University of Toronto Press Incorporated 2006 Toronto Buffalo London Printed in Canada ISBN13: 9780802091482 ISBN10: 0802091482 Printed on acidfree paper Library and Archives Canada Cataloguing in Publication Letters from heaven : popular religion in Russia and Ukraine / edited by John•Paul Himka and Andriy Zayarnyuk. ISBN13: 9780802091482 ISBN10: 0802091482 1. Russia – Religion – History. 2. Ukraine – Religion – History. 3. Religion and culture – Russia (Federation) – History. 4. Religion and culture – Ukraine – History. 5. Eastern Orthodox Church – Russia (Federation) – History. 6. Eastern Orthodox Church – Ukraine – History. I. Himka, John•Paul, 1949– II. Zayarnyuk, Andriy, 1975– BX485.L48 2006 281.9 947 C20069037116 University of Toronto Press acknowledges the financial assistance to its publishing program of the Canada Council for the Arts and the Ontario Arts Council. -

Ontario Quiz

Ontario Quiz Try our Ontario Quiz & see how well you know Ontario. Answers appear at the bottom. 1. On Ontario’s Coat of Arms, what animal stands on a gold and green wreath? A) Beaver B) Owl C) Moose D) Black Bear 2. On Ontario’s Coat of Arms, the Latin motto translates as: A) Loyal she began, loyal she remains B) Always faithful, always true C) Second to none D) Liberty, Freedom, Truth 3. Which premier proposed that Ontario would have its own flag, and that it would be like the previous Canadian flag? A) Frost B) Robarts C) Davis D) Rae 4. Ontario’s Progressive Conservative government under right wing leader Mike Harris espoused what kind of revolution? A) Law and order B) Tax deductions C) People first D) Common sense 5. Which of the following was not an Ontario Liberal leader? A) Jim Bradley B) Robert Nixon C) Mitch Hepburn D) Cecil Rhodes 6. Which of the following is not a recognized political party in Ontario? A) White Rose B) Communist C) Family Coalition D) Libertarian 7. Tim Hudak, leader of Ontario’s PC party is from where? A) Crystal Beach B) Fort Erie C) Welland D) Port Colborne 8. Former Ontario Liberal leader, Dalton McGuinty was born where? A) Toronto B) Halifax C) Calgary D) Ottawa 9. The first Ontario Provincial Police detachment was located where? A) Timmins B) Cobalt C) Toronto D) Bala 10. The head of the OPP is called what? A) Commissioner B) Chief C) Superintendent D) Chief Superintendent 11. Which of the following was not a Lieutenant Governor of Ontario? A) Hillary Weston B) John Aird C) Roland Michener D) William Rowe 12. -

The Slavic Vampire Myth in Russian Literature

From Upyr’ to Vampir: The Slavic Vampire Myth in Russian Literature Dorian Townsend Thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy School of Languages and Linguistics Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences The University of New South Wales May 2011 PLEASE TYPE THE UNIVERSITY OF NEW SOUTH WALES Thesis/Dissertation Sheet Surname or Family name: Townsend First name: Dorian Other name/s: Aleksandra PhD, Russian Studies Abbreviation for degree as given in the University calendar: School: Languages and Linguistics Faculty: Arts and Social Sciences Title: From Upyr’ to Vampir: The Slavic Vampire Myth in Russian Literature Abstract 350 words maximum: (PLEASE TYPE) The Slavic vampire myth traces back to pre-Orthodox folk belief, serving both as an explanation of death and as the physical embodiment of the tragedies exacted on the community. The symbol’s broad ability to personify tragic events created a versatile system of imagery that transcended its folkloric derivations into the realm of Russian literature, becoming a constant literary device from eighteenth century to post-Soviet fiction. The vampire’s literary usage arose during and after the reign of Catherine the Great and continued into each politically turbulent time that followed. The authors examined in this thesis, Afanasiev, Gogol, Bulgakov, and Lukyanenko, each depicted the issues and internal turmoil experienced in Russia during their respective times. By employing the common mythos of the vampire, the issues suggested within the literature are presented indirectly to the readers giving literary life to pressing societal dilemmas. The purpose of this thesis is to ascertain the vampire’s function within Russian literary societal criticism by first identifying the shifts in imagery in the selected Russian vampiric works, then examining how the shifts relate to the societal changes of the different time periods. -

Gender, Race, and Class in Media a Critical Reader

GENDER, RACE, AND CLASS IN MEDIA A CRITICAL READER 2Q GAIL DINES o Wheelock College b JEAN M. HUMEZ UJ University of Massachusetts, Boston Los Angeles I London I New Delhi Singapore I Washington DC TENTS Preface to the Third Edition XI Acknowledgments xv PART I. A CULTURAL STUDIES APPROACH TO MEDIA: THEORY 1 1. Cultural Studies, Multiculturalism, and Media Culture 7 Douglas Kellner 2. The State of Media Ownership and Media Markets: Competition or Concentration and Why Should We Care? 19 Dwayne Winseck 3. The Meaning of Memory: Family, Class, and Ethnicity in Early Network Television Programs 25 George Lipsitz 4. Hegemony 33 James Lull 5. Extreme Makeover: Home Edition: An American Fairy Tale 37 Gareth Palmer 6. Women Read the Romance: The Interaction of Text and Context 45 Janice Radway 7. Star Trek Rerun, Reread, Rewritten: Fan Writing as Textual Poaching 57 Henry Jenkins lIT PART II. REPRESENTATIONS OF GENDER, RACE, AND CLASS 67 8. Hetero Barbie? 71 Mary F. Rogers 9. Sex and the City: Carrie Bradshaw's Queer Postfeminism 75 Jane Gerhard 10. The Whites of Their Eyes: Racist Ideologies and the Media 81 Stuart Hall 11. Pornographic Eroticism and Sexual Grotesquerie in Representations of African American Sportswomen 85 James McKay and Helen Johnson 12. What Does Race Have to Do With Ugly Betty? An Analysis of Privilege and Postracial(?) Representation on a Television Sitcom 95 Jennifer Esposito 13. Ralph, Fred, Archie, Homer, and the King of Queens: Why Television Keeps Re-Creating the Male Working-Class Buffoon 101 Richard Butsch PART III. READING MEDIA TEXTS CRITICALLY 111 14. -

Representations of Bisexual Women in Twenty-First Century Popular Culture

Straddling (In)Visibility: Representations of Bisexual Women in Twenty-First Century Popular Culture Sasha Cocarla A thesis submitted to the Faculty of Graduate and Postdoctoral Studies in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Doctorate of Philosophy in Women's Studies Institute of Feminist and Gender Studies Faculty of Social Sciences University of Ottawa © Sasha Cocarla, Ottawa, Canada 2016 Abstract Throughout the first decade of the 2000s, LGBTQ+ visibility has steadily increased in North American popular culture, allowing for not only more LGBTQ+ characters/figures to surface, but also establishing more diverse and nuanced representations and storylines. Bisexuality, while being part of the increasingly popular phrase of inclusivity (LGBTQ+), however, is one sexuality that not only continues to be overlooked within popular culture but that also continues to be represented in limited ways. In this doctoral thesis I examine how bisexual women are represented within mainstream popular culture, in particular on American television, focusing on two, popular programs (The L Word and the Shot At Love series). These texts have been chosen for popularity and visibility in mainstream media and culture, as well as for how bisexual women are unprecedentedly made central to many of the storylines (The L Word) and the series as a whole (Shot At Love). This analysis provides not only a detailed historical account of bisexual visibility but also discusses bisexuality thematically, highlighting commonalities across bisexual representations as well as shared themes between and with other identities. By examining key examples of bisexuality in popular culture from the first decade of the twenty- first century, my research investigates how representations of bisexuality are often portrayed in conversation with hegemonic understandings of gender and sexuality, specifically highlighting the mainstream "gay rights" movement's narrative of "normality" and "just like you" politics. -

Final Program

In Memoriam: Final Program XXV Congress of the International Society on Thrombosis and Haemostasis and 61st Annual SSC Meeting June 20 – 25, 2015 Toronto, Canada www.isth2015.org 1 Final Program Table of Contents 3 Venue and Contacts 5 Invitation and Welcome Message 12 ISTH 2015 Committees 24 Congress Support 25 Sponsors and Exhibitors 27 ISTH Awards 32 ISTH Society Information 37 Program Overview 41 Program Day by Day 55 SSC and Educational Program 83 Master Classes and Career Mentorship Sessions 87 Nurses Forum 93 Scientific Program, Monday, June 22 94 Oral Communications 1 102 Plenary Lecture 103 State of the Art Lectures 105 Oral Communications 2 112 Abstract Symposia 120 Poster Session 189 Scientific Program, Tuesday, June 23 190 Oral Communications 3 198 Plenary Lecture 198 State of the Art Lectures 200 Oral Communications 4 208 Plenary Lecture 209 Abstract Symposia 216 Poster Session 285 Scientific Program, Wednesday, June 24 286 Oral Communications 5 294 Plenary Lecture 294 State of the Art Lectures 296 Oral Communications 6 304 Abstract Symposia 311 Poster Session 381 Scientific Program, Thursday, June 25 382 Oral Communications 7 390 Plenary Lecture 390 Abstract Symposia 397 Highlights of ISTH 399 Exhibition Floor Plan 402 Exhibitor List 405 Congress Information 406 Venue Plan 407 Congress Information 417 Social Program 418 Toronto & Canada Information 421 Transportation in Toronto 423 Future ISTH Meetings and Congresses 2 427 Authors Index 1 Thank You to Everyone Who Supported the Venue and Contacts 2014 World Thrombosis Day -

Hudak Headed for Majority in Ontario: Poll

Hudak headed for majority in Ontario: poll Peter Kuitenbrouwer | Jun 26, 2011 – 4:35 PM ET | Last Updated: Jun 26, 2011 5:17 PM ET Tim Hudak’s Progressive Conservatives are heading to a majority government in the Ontario election on Oct.6, a new poll by Forum Research suggests. The poll of 3,198 people, a large sample size, suggests that 41% of Ontario voters will vote for the PCs, 26% support the reigning Liberal Party, 22% want the NDP to win, and 8% back the Green Party. The poll found the Tories and Liberals neck-in-neck in Toronto, whereas in Eastern Ontario 50% support the Tories compared to just 25% for the Liberals in that region. Lorne Bozinoff, president of Forum Research, said Sunday that, although the election is still over three months away, much of that is during the sleepy summer months, giving the Liberals precious little time to make up the wide gap in voter preference. “We did learn from a couple of months ago [in the federal election] that campaigns do matter,” Mr. Bozinoff said. “Nobody predicted what happened with the NDP. Still, it’s hard to see how the Ontario Liberals are going to gain traction if they release their platform in the summer.” He said the poll, conducted last Tuesday and Wednesday, suggests that conservatism in Ontario is “the new norm,” with the provincial intentions mimicking strong support for Rob Ford in Toronto and for Conservatives federally. The poll suggests the Liberals will get their clocks cleaned in greater Toronto, losing 16 of their 905 seats and 11 of the seats they hold in the 416.