Pathways to Resilience: Formal Service and Informal Support Use Patterns Among Youth in Challenging Social Ecologies

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

TOBACCO WORLD RETAIL PRICES (Ovor 5,000 Retail PI-ICM)

THE CIGAR AND THE TOBACCO WORLD THE POPULAR JOURNAL TOBACCO OVER 40 YEARS OF TRADE USEFULNESS WORLD The Subscription includes : TOBACCO WORLD RETAIL PRICES (Ovor 5,000 Retail PI-ICM). RETAIL PRICES THE TOBACCO WORLD ANNUAL (Containing a word of Trad* Brand*—with Nam* and Addrau In each cms*). Membership of: TOBACCO WORLD SERVICE JUNE 1935 (With Pott Fnta raplUa In all Trad* difficult!**). The Cigar & Tobacco World HIYWOOO A COMPANY LTD. Dmrr How*, Kin—U 3tr*M, Ontry Una, London, W.C1 trantfc OACM f Baadmur. •trmlnfhtn, Uteanar. ToWfTHM i OffUlfrunt, Phono, LonAon. •Phono I TomaU far M1J Published by THE CIGAR & TOBACCO WORLD HEYWOOD & CO., LTD. DRURY HOUSE, RUSSELL STREET, DRURY LANE, LONDON, W.C.2 Branch Offices: MANCHESTER, BIRMINGHAM, LEICESTER Talagrarm : "Organigram. Phono, London." Phono : Tampla Bar MZJ '' Inar) "TOBACCO WORLD" RETAIL PRICES 1935 Authorised retail prices of Tobaccos, Cigarettes, Fancy Goods, and Tobacconists' Sundries. ABDULLA & Co., Ltd. (\BDULD^ 173 New Bond Street, W.l. Telephone; Bishopsgnte 4815, Authorised Current Retail Prices. Turkish Cigarettes. Price per Box of 100 50 25 20 10 No. 5 14/6 7/4 3/8 — 1/6 No. 5 .. .. Rose Tipped .. 28/9 14/6 7/3 — 3/- No. 11 11/8 5/11 3/- - 1/3 No. II .. .. Gold Tipped .. 13/S 6/9 3/5 - No. 21 10/8 5/5 2/9 — 1/1 Turkish Coronet No. 1 7/6 3/9 1/10J 1/6 9d. No. "X" — 3/- 1/6 — — '.i^Sr*** •* "~)" "Salisbury" — 2/6 — 1/- 6d. Egyptian Cigarettes. No. 14 Special 12/5 6/3 3/2 — — No. -

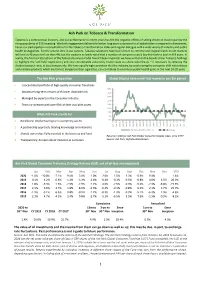

Ash Park on Tobacco & Transformation

Ash Park on Tobacco & Transformation Tobacco is a controversial industry, and our performance in recent years has felt the negative effects of selling driven at least in part by the rising popularity of ESG investing. We think engagement delivers far better long-term outcomes for all stakeholders compared to divestment, hence our participation in consultations for the Tobacco Transformation Index and regular dialogue with a wide variety of industry and public health protagonists. For the second time in our careers, Tobacco valuations have been driven to extreme and illogical levels: credit markets will lend at 40 years for less than 4%, but the equity is so lowly-rated that a number of companies could buy themselves back in 8-9 years. In reality, the financial attractions of the Tobacco business model haven’t been impaired; we have written to the boards of our Tobacco holdings to highlight the ‘self-help’ opportunity and very considerable value they could create via share repurchases – if necessary by rebasing the dividend payout ratio, at least temporarily. We have equally high conviction that the industry, by accelerating the consumer shift into tobacco and nicotine products which are far less dangerous than cigarettes, can contribute to enormous public health gains in the next 10-20 years. The Ash Park proposition Global Staples have never lost money in any 5yr period • Concentrated portfolio of high-quality consumer franchises 40% • Attractive long-term returns with lower downside risk 35% 30% • Managed by experts in the Consumer industry 25% • Team co-invested with over 90% of their available assets 20% 15% 10% What Ash Park stands for 5% 1. -

Final Program

In Memoriam: Final Program XXV Congress of the International Society on Thrombosis and Haemostasis and 61st Annual SSC Meeting June 20 – 25, 2015 Toronto, Canada www.isth2015.org 1 Final Program Table of Contents 3 Venue and Contacts 5 Invitation and Welcome Message 12 ISTH 2015 Committees 24 Congress Support 25 Sponsors and Exhibitors 27 ISTH Awards 32 ISTH Society Information 37 Program Overview 41 Program Day by Day 55 SSC and Educational Program 83 Master Classes and Career Mentorship Sessions 87 Nurses Forum 93 Scientific Program, Monday, June 22 94 Oral Communications 1 102 Plenary Lecture 103 State of the Art Lectures 105 Oral Communications 2 112 Abstract Symposia 120 Poster Session 189 Scientific Program, Tuesday, June 23 190 Oral Communications 3 198 Plenary Lecture 198 State of the Art Lectures 200 Oral Communications 4 208 Plenary Lecture 209 Abstract Symposia 216 Poster Session 285 Scientific Program, Wednesday, June 24 286 Oral Communications 5 294 Plenary Lecture 294 State of the Art Lectures 296 Oral Communications 6 304 Abstract Symposia 311 Poster Session 381 Scientific Program, Thursday, June 25 382 Oral Communications 7 390 Plenary Lecture 390 Abstract Symposia 397 Highlights of ISTH 399 Exhibition Floor Plan 402 Exhibitor List 405 Congress Information 406 Venue Plan 407 Congress Information 417 Social Program 418 Toronto & Canada Information 421 Transportation in Toronto 423 Future ISTH Meetings and Congresses 2 427 Authors Index 1 Thank You to Everyone Who Supported the Venue and Contacts 2014 World Thrombosis Day -

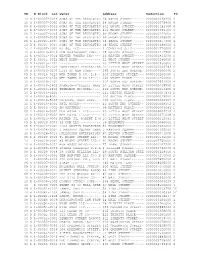

Actions on Applications in 2010

YR B Block Lot Owner Address Reduction TC 10 R 1-00007-0029 SONS OF THE REVOLUTIO 26 WATER STREET~~~~~~ 0000000048200 4 10 R 1-00007-0030 SONS OF THE REVOLUTIO 24 WATER STREET~~~~~~ 0000000075400 4 09 R 1-00007-0033 SONS OF THE REVOLUTIO 101 BROAD STREET~~~~~ 0000000183700 4 10 R 1-00007-0033 SONS OF THE REVOLUTIO 101 BROAD STREET~~~~~ 0000000386500 4 09 R 1-00007-0035 SONS OF THE REVOLUTIO 99 BROAD STREET~~~~~~ 0000000244000 4 10 R 1-00007-0035 SONS OF THE REVOLUTIO 99 BROAD STREET~~~~~~ 0000000305500 4 09 R 1-00007-0037 SONS OF THE REVOLUTIO 58 PEARL STREET~~~~~~ 0000000277800 4 10 R 1-00007-0037 SONS OF THE REVOLUTIO 58 PEARL STREET~~~~~~ 0000000389000 4 10 R 1-00007-1001 BZ 66, LLC~~~~~~~~~~~ 1 COENTIES SLIP~~~~~~ 0000001770000 4 10 R 1-00010-0019 JMW RESTAURANT CORP~~ 25 BRIDGE STREET~~~~~ 0000000217500 4 10 R 1-00011-0014 BEAVER TOWERS INC~~~~ 26 BEAVER STREET~~~~~ 0000000813000 2 10 R 1-00015-0022 WEST EDEN~~~~~~~~~~~~ 21 WEST STREET~~~~~~~ 0000000280000 2 09 R 1-00015-1101 ~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~ 20 LITTLE WEST STREET 0000000950000 4 10 R 1-00015-1102 TWENTYWEST PROPERTIES 20 LITTLE WEST STREET 0000000003783 2 09 R 1-00016-0100 CITY OF NEW YORK~~~~~ 345 SOUTH END AVENUE~ 0000005600000 2 09 R 1-00016-0120 WFP TOWER A CO. L.P.~ 200 LIBERTY STREET~~~ 0000010200000 4 09 R 1-00016-0150 WFP TOWER D CO LP~~~~ 250 VESEY PLACE~~~~~~ 0000010250000 4 10 R 1-00016-1301 ~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~ 102 NORTH END AVENUE~ 0000007661000 4 10 R 1-00016-1402 SCANLON-O'KELLY, MARY 30 LITTLE WEST STREET 0000000018585 2 09 R 1-00016-2200 ZEMELMAN MICHAEL~~~~~ -

Delinquent Tax Report Page 1 of 160 Lancaster County 3/5/2020 10:31:13 Claim Years Range: 1997 - 2019 Selected Criteria: Municipality

Delinquent Tax Report Page 1 of 160 Lancaster County 3/5/2020 10:31:13 Claim Years Range: 1997 - 2019 Selected Criteria: Municipality Parcel No Owner Site Address Total Due Years 380-56271-3-0008 1,762.93 2012,2013,2014,2015,2016,*** 150-15014-0-0000 105 N RIVER ST LP 105 N RIVER ST 56,631.55 2019 150-35174-0-0000 105 N RIVER ST LP 30 E JACOB ST 1,152.69 2019 336-40108-0-0000 119 E WALNUT LLC 119 E WALNUT ST 2,821.40 2019 490-02538-0-0000 13 HERSHEY REAL ESTATE LP 13 HERSHEY AVE 7,747.04 2019 334-35588-0-0000 130 S PRINCE STREET LLC 130 S PRINCE ST 306.58 2019 400-63469-0-0000 135 SOUTH CHARLOTTE STREET PROPERTY135 S LPCHARLOTTE ST 2,251.31 2019 250-47847-0-0000 145-147 HIGH ST APTS LP 145 W HIGH ST 2,443.43 2019 390-13578-1-0101 150 FARMINGTON LLC 150 FARMINGTON LN UNIT 101 2,840.25 2019 390-13578-1-0102 150 FARMINGTON LLC 150 FARMINGTON LN UNIT 102 942.81 2019 390-13578-1-0103 150 FARMINGTON LLC 150 FARMINGTON LN UNIT 103 1,361.62 2019 390-13578-1-0104 150 FARMINGTON LLC 150 FARMINGTON LN UNIT 104 173.59 2019 390-13578-1-0105 150 FARMINGTON LLC 150 FARMINGTON LN UNIT 105 306.93 2019 390-13578-1-0106 150 FARMINGTON LLC 150 FARMINGTON LN UNIT 106 1,168.46 2019 390-13578-1-0107 150 FARMINGTON LLC 150 FARMINGTON LN UNIT 107 368.45 2019 390-13578-1-0108 150 FARMINGTON LLC 150 FARMINGTON LN UNIT 108 118.89 2019 390-13578-1-0109 150 FARMINGTON LLC 150 FARMINGTON LN UNIT 109 262.48 2019 400-55698-0-0000 150 SOUTH CHARLOTTE STREET PROPERTY150 S LPCHARLOTTE ST 2,968.29 2019 300-76314-0-0000 1500 STONY BATTERY LP 1500 STONY BATTERY RD 28,278.03 -

Annual Report and Accounts 06

Annual Report and Accounts 06 Annual Review and Summary Financial Statement and Directors’ Report and Accounts 2006 WorldReginfo - 98675577-a5f8-41aa-ac01-37c1b8bcb2da About this combined Report The format of our reporting has been changed to accommodate the inclusion, for the first time, of an Operating and Financial Review (OFR). In preparing the OFR, we have sought to take into account, where considered appropriate, the best practice set out in the UK Accounting Standards Board’s ‘Reporting Statement: Operating and Financial Review’. We have responded to the spirit of the OFR by offering shareholders a balanced and comprehensive analysis of our current business and describing the significant industry trends that are likely to influence our future prospects. For the first time, we have published our Key Performance Indicators, some other important Business Measures and the Group’s Key Risk Factors. We have also attempted to avoid having too much information in one publication. Our corporate website bat.com has a wealth of material about the Group and, in May 2007, we plan to publish our latest Social Report, detailing progress during 2006 on a range of commitments and actions. We will carefully consider the structure and content of our future reporting in the light of developments in the field and the advice and comments we receive about this publication. The full content of this combined Report is under this flap. Leave it open as a reference to find your way to the different topics covered. Cautionary Statement: the Operating and Financial Review and certain other sections of this document contain forward looking statements which are subject to risk factors associated with, among other things, the economic and business circumstances occurring from time to time in the countries and markets in which the Group operates. -

Inside: the ANDREWS UNIVERSITY MAGAZINE FALL 2015

FALL 2015 FALL THE ANDREWS UNIVERSITY MAGAZINE MAGAZINE THE ANDREWS UNIVERSITY inside: 2015 Alumni Homecoming Weekend | #aulivewholly | Annual Report 2015 Vol 51 No 4 » from the President’s desk in focus FThe AndrewsOCUS University Magazine Editor Patricia Spangler (BS ’04) [email protected] | 269-471-3315 Higher education: troublemaker Contributing Editors Tami Condon (BS ’91, MA ’13) or change agent? Becky St. Clair Designer Niels-Erik Andreasen Matt Hamel (AT ’05) President Photographers Daniel Duffis (current student) American higher education is delivered by 4,000–6,000 (depending on how one counts) diverse, Tanya Ebenezer (current student) Darren Heslop (BFA ’10) expensive and at times unruly institutions! Adventist higher education is provided by 114 Andriy Kharkovyy (BBA ’06, MBA ’09) institutions, 14 of them in North America. They are more “orderly,” but even so from time to time Sarah Lee (BT ’02) both church members and leaders raise their eyebrows at our colleges. What has become of our Heidi Ramirez (current student) David Sherwin (BFA ’82) traditional, family-style campuses of yesteryear, and why do our sweet Sabbath School children Brian Tagalog (current student) grow up and go to college, they wonder! Well perhaps it is precisely those diverse, inefficient and at times unruly institutions that make college education so dynamic and effective. Think of the recent student demonstrations in the universities of Missouri, Yale and elsewhere—a bit messy perhaps, but they received national attention and things are changing. I admit some of this campus activity can be disconcerting and is not a really effective way of running a university, but it does draw attention to critical issues, raise important questions, propose solutions, and help make education a change agent in our society and also in our church. -

Kingsway Regional School District

KINGSWAY REGIONAL SCHOOL DISTRICT 2017‐2018 Committed to Excellence Program Planning Guide Middle School & High School Kingsway Regional School District Grades 7‐12 Program Planning Guide 2017‐2018 Notice of Non-Discrimination The Board of Education declares it to be the policy of the Kingsway Regional School District that each and every student in the school system shall be provided equal opportunities to achieve his or her maximum potential through enrollment in the programs offered in the schools unhindered by any discriminatory attitudes or practices based on distinctions of race, color, creed, religion, gender, ancestry, national origin, place of residence, handicap, or social or economic background. The following persons have been designed to handle inquiries regarding the non-discrimination policies and serve the district and community as the Affirmative Action Officers. Mr. Michael Schiff Ms. Patricia Calandro Supervisor of Pupil Personnel Services Chief Academic Officer 213 Kings Highway 213 Kings Highway Woolwich Twp., NJ 08085 Woolwich Twp., NJ 08085 (856) 467-3300 (856) 467-3300 2 Kingsway Regional School District 213 Kings Highway Woolwich Twp., NJ 08085 P: (856) 467‐3300 F: (856) 241‐1932 CEEB/ACT COLLEGE CODE: 311445 SCHOOL CLOSING NUMBER: 815 Table of Contents A Message from the Superintendent ................................................................................................................................... 5 Preface ..................................................................................................................................................................................... -

Active Operator Report 10-1-19.Xlsx

Active Meals and Rentals Tax Operators by Business Name as of October 1, 2019 Street Street License Business Entity Address Address Number Name Name Line 1 Line 2 City 47099 #6 RIVER & PINES CONDOMINIUMS WATTS WILLIAM 16 OLD RTE BARTLETT 65349 @RINCHA EKAPORN SAKTANASET 80 CONTINENTAL BLVD UNIT B MERRIMACK 64271 10 FRANCIS STREET 10 FRANCIS STREET LLC 10 FRANCIS ST HAMPTON 59441 10 RIDGEWOOD POINT RENTAL BOB AND SHANNON KRIEGER 10 RIDGEWOOD POINT RD SUNAPEE 46386 100 CLUB 100 CLUB CONCEPTS INC 100 MARKET ST STE 500 PORTSMOUTH 61097 100 MILE MARKET 100 MILE MARKET LLC 35 PLEASANT STREET CLAREMONT 63081 1025 LACONIA ROAD LAURA JOHNSON 1025 LACONIA RD TILTON 53640 104 DINER THE THE 104 DINER INC 752 ROUTE 104 NEW HAMPTON 60862 106 HAMEL RD SUNAPEE N.H. RENTAL MARK & HOLLY ADAMY 106 HAMEL RD SUNAPEE 58932 107 PIERCE RD WHITEFIELD NH MICHAEL & KRISTEN HARVEY 107 PIERCE ROAD WHITEFIELD 27480 107 PIZZERIA & RESTAURANT FREMONT HOUSE OF PIZZA INC 431 MAIN ST FREMONT 59204 108 EXPRESS MINI MART 108 EXPRESS MINI MART INC 21 SOUTH MAIN ST NEWTON 64309 110 GRILL 110 GRILL ES MANCHESTER LLC 875 ELM STREET MANCHESTER 59490 110 GRILL 110 GRILL TWO LLC 27 TRAFALGAR SQUARE NASHUA 61812 110 GRILL 110 GRILL RM ROCHESTER LLC 136 MARKETPLACE BLVD ROCHESTER 63344 110 GRILL 110 GRILL SL STRATHAM LLC 19 PORTSMOUTH AVE STRATHAM 64876 110 GRILL 110 GRILL WLNH, LLC 250 N PLAINFIELD ROAD WEST LEBANON 64113 12 LAKE STREET 12 LAKE STREET, LLC 144 LAKE ST UNIT #12 LACONIA 62017 12 OCEAN GRILL ELI SOKORELIS 12 OCEAN BLVD SEABROOK 38298 12% SOLUTION HAMEL MICHAEL 994 -

C Fr.- ~ Vi/J/ J Tf !3 Avanr- PRŒCS

COMMISSION DES COMMUNAUTES EUROPEENNES DIRECTION GENERALE DU DEVELOPPEMENT ET DE LA COOPERATION DIRECTION DES ECHANGES COMMERCIAUX ET DU DEVELOPPEMENT Il Il Il Il Il Il Il POSSIBILITES DE CREATION D'INDUSTRIES EXPORTATRICES DANS LES ETATS AFRICAINS ET MALGACHE ASSOCIES FABRICATION DE CIGARES ET CIGARILLOS MAl 1974 VIII/226(74)-F c Fr.- ~ vi/J/ J tf !3 AVANr- PRŒCS Considérant la priorité donnée par la deuxième Convention d'Association (Yaoundéii) à l'objectif d'industrialisation des Etats Africains et Malgache Associés et les perspectives que certaines productions manufacturières desti nées à 1 'exportation pourraient offrir à certains de ces Etats, la Commission des Communautés Européennes a fait réaliser, avec l'accord des Etats Associés, un programme d'études sur les possibilités de créer certaines industries d'exportation dans ces pa;ys. Ce programme d'études sectorielles concerne les productions ou ensembles homogènes de produits suivants -produits de l'élevage • viande • cuirs et peaux • chaussures • articles en cuir - produits électriques et électroniques • produits électro-mécaniques • produits électroniques -transformation du bois et fabrication d'articles en bois • première transformation (sciages, déroulages, tranchages) • deuxième transformation (profilés, moulures, contreplaqués, panneaux) • produits finis (pour la construction et l'ameublement) production sidérurgique • pelletisation du minerai de fer et électre-sidérurgie • ferro-alliages (ferro-silicium, -manganèse et -nickel) conserves et préparations de fruits tropicaux -

2014-2015 Guide

2014-2015 GUIDE A PUBLICATION OF THE CHAMBER OF COMMERCE OF HUNTSVILLE/MADISON COUNTY AL-06088149-01 2014-2015 Guide To table of contents HUNTSVILLE Madison County, Alabama Chamber Staff. Published by 4 Alabama Media Group Editorial and advertising offices located at Letter from the Chairman of the Board. .5 200 Westside Square, Suite 100 Huntsville, AL 35801 Chamber Executive Committee. 6 DIRECTOR, AUDIENCE SOLUTIONS Jane Katona [email protected] Chamber Board of Directors. .8 PUBLICATION DIRECTOR Carl Bates [email protected] Economic Development. 11 MANAGING EDITOR Terry Schrimscher Huntsville Arts. 18 ART DIRECTORS Elizabeth Chick Huntsville/Madison County Schools . Patricia Lay 22 PRODUCTION Don Taylor Huntsville/Madison County by the Numbers. .26 [email protected] 2014-2015 Annual Guide to Huntsville/ Huntsville/Madison County Public Services. 28 Madison County, Alabama, is published by Alabama Media Group for the Chamber of Commerce of Huntsville/Madison County Huntsville/Madison County Parks . 37 For membership information, contact: Chamber of Commerce of Business in Huntsville/Madison County. Huntsville/Madison County 41 225 Church Street Huntsville, AL 35801 256.535.2000 phone Huntsville/Madison County Real Estate. .56 256.535.2015 fax www.hsvchamber.org For more information about this 10 Things To Do in Huntsville/Madison County. .60 publication, call 205.325.2237. Alabama Media Group also produces area guides, magazines and other Revitalization. specialty publications. 68 Copyright©2014 Alabama Media Group. All rights reserved. Reproduction -

Daniel 202 1 Edition Dr

Notes on Daniel 202 1 Edition Dr. Thomas L. Constable BACKGROUND <* Granicus R. Issus Carchemish * * * Gaugamela Jerusalem * Babylon * * Susa Indus R. IMPORTANT SITES IN DANIEL In 605 B.C., Prince Nebuchadnezzar led the Babylonian army of his father Nabopolassar against the allied forces of Assyria and Egypt. He defeated them at Carchemish near the top of the Fertile Crescent. This victory gave Babylon supremacy in the ancient Near East. With Babylon's victory, Egypt's vassals, including Judah, passed under Babylonian control. Shortly thereafter that same year Nabopolassar died, and Nebuchadnezzar succeeded him as king. Nebuchadnezzar then moved south and invaded Judah, also in 605 B.C. He took some royal and noble captives to Babylon (Dan. 1:1-3), including Daniel, plus some of the vessels from Solomon's Copyright Ó 2021 by Thomas L. Constable www.soniclight.com 2 Dr. Constable's Notes on Daniel 2021 Edition temple (2 Chron. 36:7). This was the first of Judah's three deportations in which the Babylonians took groups of Judahites to Babylon. The king of Judah at that time was Jehoiakim (2 Kings 24:1-4). Jehoiakim's son Jehoiachin (also known as Jeconiah and Coniah) succeeded him in 598 B.C. Jehoiachin reigned only three months and 10 days (2 Chron. 36:9). Nebuchadnezzar invaded Judah again. At the turn of the year, in 597 B.C., he took Jehoiachin to Babylon, along with most of Judah's remaining leaders, including young Ezekiel, and the rest of the national treasures (2 Kings 24:10-17; 2 Chron. 36:10).