Vancouver Police Board Street Check Review

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Reintegration Program: Does Your Organization Need to Build One?

Reintegration Program: Does Your Organization Need to Build One? About the EPS Reintegration Program Since its inception in 2009, the peer-driven EPS Reintegration Program has assisted first responders and other public safety personnel in returning to work after a critical incident or long-term absence from the workplace due to a physical or psychological injury. Members of the Reintegration Team do their work in partnership with clinicians and other stakeholders (e.g. Workers’ Compensation Board) to build the member’s return-to-work plan. The program has two streams, each with its own goal: 1. Short term. Delivered after involvement in a critical event such as, officer involved shootings, major collisions, attempted disarmings, serious assaults, fatalities and more. It is intended to be delivered post event and prior to a psychological injury. One hundred and seventy EPS members have accessed this program to date. 2. Long term. Focused on returning members to work after a physical and/or psychological injury has occurred. It is possible that there has been a leave of absence from the workplace, a need for modified duties or a possibility that they are your organization’s “Working Wounded”. Seventy-five EPS members have accessed this program to date. *In the last three years, The Reintegration Team has also worked with members in the disciplinary process on a voluntary basis. This has had the effect of helping members to feel invested in continuing to work on areas for growth while awaiting decisions from inquiries. How Does the Long Term Program Work? If dealing with a psychological injury, members will work with their clinical and reintegration team to build a personalized list of stress-inducing environments, situations, and/ or equipment (e.g. -

2020-2022 EPS Strategic Plan

STRATEGIC PLAN 2020-2022 Edmonton Police Service STRATEGIC PLAN 2020–2022 A Message from Leadership 3 EPS by the Numbers 6 TABLE OF CONTENTS TABLE State of Policing 8 Our Planning Process 10 At a Glance 12 GOAL 1 : BALANCE SUPPORT AND 15 ENFORCEMENT GOAL 2: PARTNER AND ADVOCATE 16 GOAL 3: INNOVATE AND ADVANCE 17 GOAL 4: GROW DIVERSE TALENTS 18 Reporting Process 21 Indicators 22 B Edmonton Police Service STRATEGIC PLAN 2020–2022 Edmonton Police Service STRATEGIC PLAN 2020–2022 1 VISION A forward-thinking police service that strengthens public trust through A MESSAGE FROM addressing crime, harm Dale R. McFee Chief of Police and disorder. Few things of great measure can be accomplished without teamwork, and the same is true of the Edmonton Police Service’s 2020-2022 Strategic Plan. Forging a new path that focuses on reducing demands for service and being relentless on crime requires strong partnerships, and the Edmonton Police Service (EPS) is fortunate to have the Edmonton Police Commission (EPC) and the Edmonton Police Association (EPA) help in setting a new direction for success. MESSAGE FROM LEADERSHIP MESSAGE VISION, MISSION AND VALUES VISION, MISSION Edmonton is a growing city, and as it evolves so must our approach to policing. MISSION Calls for service are consistently increasing, placing more and more strain on our frontlines. Repeat calls have created an arrest/remand/release cycle that has grown to consume too much of our time and resources. We can only ask so much more of To be relentless on crime the frontlines: instead, we are asking ourselves how we can do things differently. -

2009-2010 Athlete Carding

2009-2010 ATHLETE CARDING Senior Provincial Carding - Thirty Cards: The top 30 FINA scoring swimmers based on Olympic events from selected Long Course competitions. Funding level is based on the following FINA Point thresholds. Performance Threshold 900+ FINA Points = $6000 880 FINA Points = $5000 850 FINA Points = $4000 800 FINA Points = $3000 Junior Provincial Carding – Ten Cards: The top 5 FINA scoring females 16 & under and the top 5 FINA scoring males 17 & under each receive $1000, (10 X $1000 = $10,000); excluding swimmers who qualify for the Senior Carding (30 spots). Selected Long Course Competitions in 2009 - Ontario Carding. • Junior Pan Pacific Swimming Championships (January - Guam) • Australian Youth Olympic Festival (January - Australia) • 2009 Charlotte UltraSwim - (May - North Carolina) • Grand Prix Mel Zajac International • Grand Prix Quebec Cup • Swim Ontario Long Course Senior Championships (June - Etobicoke) • Swim Ontario Junior Provincials (July - Etobicoke) • World University Games (July - Serbia) • SNC Summer Nationals (July - Montreal) • Canadian Age Group Championships (July - Montreal) • 13th FINA World Championships (July/August – Italy) • Long Course Dual Meet (August - Great Britain) TBC • North American Challenge Cup (August - Mexico) 1 Criteria and Guidelines Payment: • Carding money is payable to the individual athlete. • Ontario Residents: Receive 50% after the SNC Canada Cup in November 2009, and 50% after the SNC Spring Nationals in April 2010. • Out of Province Swimmers: Funding will be prorated on the amount of time (monthly basis) the athlete resides and trains in Ontario during the competitive season (September 2009 to August 20010). Payment will be made after SNC Spring Nationals in April 2010. It is the responsibility of the athlete (or their family) to notify Swim Ontario with proof of athlete residence and training conditions. -

2021-06-15 Joint TPP Complaint Final

Vancouver Police Board 2120 Cambie Street Vancouver, BC V56 4N6 Via Email June 15, 2021 Dear Police Board Members, RE: Service & Policy Complaint Regarding the VPD Trespass Prevention Program On January 28, 2021, a group of seven Indigenous, women’s, Downtown Eastside and legal organizations voiced their opposition to the Trespass Prevention Program.1 Despite the concerns raised, the Trespass Prevention program has not been cancelled. We understand that businesses and stratas are still able to qualify for the program, which authorizes all police officers of the Vancouver Police Department (VPD) to act as authorized representatives and take enforcement action based on VPD officers’ reasonable belief that the person is acting in contravention to the BC Trespass Act.2 Further to the statement issued in January 2021, we are now filing a Service and Policy Complaint in accordance with s. 168 of British Columbia’s Police Act. 1 https://www.pivotlegal.org/end_trespass_prevention_program 2 Vancouver Police Department, “Trespass Prevention Program” intake form (Appendix A) In light of the reviews initiated by the Director of Police Services into how the VPD board handled a previous service and policy complaint,3 we expect the board to consider the relevant and available findings of the review(s) in its response to this complaint. Complaint Specifically, we are writing to complain about the inappropriate creation of the Trespass Prevention Program (TPP), as reported by the VPD in a report dated October 19, 2020.4 Based on VPD Report 2010C02, the VPD describes a TPP as an initiative that was recently launched, “which gives police written consent from the property owner to move along unwanted parties from private property.”5 We submit that the lack of transparency about how the TPP has been initiated and managed highlights fundamental problems related to the general direction and management of the VPD as well as the inadequacy and inappropriateness of VPD internal procedures and policies. -

Policing and Surveilling the Black Community in Toronto, Canada, 1992-2016

From the Yonge Street Riot to the Carding Controversy: Policing and Surveilling the Black Community in Toronto, Canada, 1992-2016 By Maria Kyres A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate Program in Cultural Studies in Conformity with the requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts Queen’s University Kingston, Ontario, Canada September, 2017 Copyright © Maria Kyres Abstract In the last decade, the conversation surrounding racial profiling and carding in the city of Toronto garnered much public and scholarly attention. Many journalists, academics and activists have examined the Community Contacts Policy, also known as carding, as well as mass incarceration and the police shootings and killings of unarmed, young Black men. The Yonge Street Uprising and the carding controversy in Toronto serve as two case studies to explore the ways that Black men have been disproportionately profiled, policed and surveilled in this country, particularly in the province of Ontario. Despite the fact that the Yonge Street Uprising and the carding controversy occurred decades apart, a common thread throughout both cases was the narrative of Black male criminality. In addition, it became apparent that many of the practices employed in contemporary society, such as racial profiling, carding and mass incarceration were derived from slavery, with the goal of limiting the freedom and mobility of Black people. Therefore, an examination of Canada’s historical treatment of Black people is necessary in order to demonstrate how practices rooted in slavery, such as, fugitive slave advertisements and historical representations of Black criminality helped inform current police practices. Through an analysis of historical, legal, criminological, and critical race scholarship, this work seeks to examine how and why Black people, specifically Black men, were and continue to be disproportionately more likely to be policed, surveilled and incarcerated. -

(202) 514-1888 Canadian Man Sentenced To

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE CRM WEDNESDAY, AUGUST 25, 2010 (202) 514-2008 WWW.JUSTICE.GOV TDD (202) 514-1888 CANADIAN MAN SENTENCED TO 33 MONTHS IN PRISON FOR SELLING COUNTERFEIT CANCER DRUGS USING THE INTERNET WASHINGTON – Hazim Gaber, 22, of Edmonton, Canada, was sentenced today in Phoenix by U.S. District Court Judge James A. Teilborg to 33 months in prison for selling counterfeit cancer drugs using the Internet, announced Assistant Attorney General Lanny A. Breuer of the Criminal Division, U.S. Attorney Dennis Burke for the District of Arizona and FBI Special Agent in Charge of the Phoenix Field Office Nathan T. Gray. Judge Teilborg also ordered Gaber to pay a $75,000 fine, as well as $53,724 in restitution, and to serve three years of supervised release following his prison term. Gaber was indicted by a federal grand jury in Phoenix on June 30, 2009, on five counts of wire fraud for selling counterfeit cancer drugs through the website DCAdvice.com. Gaber was arrested on July 25, 2009, in Frankfurt, Germany, and was extradited to the United States on Dec. 18, 2009. At his plea hearing in May 2010, Gaber admitted selling what he falsely claimed was the experimental cancer drug sodium dichloroacetate, also known as DCA, to at least 65 victims in the United States, Canada, the United Kingdom, Belgium and the Netherlands between October and November 2007. Gaber also admitted to selling more than 800 pirated copies of business software between February 2007 and December 2008. As part of the plea agreement, Gaber agreed to forfeit or cancel any website, domain name or Internet services account related to this fraud scheme. -

Executive Summary

ARCHIVED - Archiving Content ARCHIVÉE - Contenu archivé Archived Content Contenu archivé Information identified as archived is provided for L’information dont il est indiqué qu’elle est archivée reference, research or recordkeeping purposes. It est fournie à des fins de référence, de recherche is not subject to the Government of Canada Web ou de tenue de documents. Elle n’est pas Standards and has not been altered or updated assujettie aux normes Web du gouvernement du since it was archived. Please contact us to request Canada et elle n’a pas été modifiée ou mise à jour a format other than those available. depuis son archivage. Pour obtenir cette information dans un autre format, veuillez communiquer avec nous. This document is archival in nature and is intended Le présent document a une valeur archivistique et for those who wish to consult archival documents fait partie des documents d’archives rendus made available from the collection of Public Safety disponibles par Sécurité publique Canada à ceux Canada. qui souhaitent consulter ces documents issus de sa collection. Some of these documents are available in only one official language. Translation, to be provided Certains de ces documents ne sont disponibles by Public Safety Canada, is available upon que dans une langue officielle. Sécurité publique request. Canada fournira une traduction sur demande. CPRC CCRP CANADIAN POLICE RESEARCH CENTRE CANADIEN DE CENTRE RECHERCHES POLICIÈRES TR-02-2003 "Collapsible Baton" Officer Safety Unit – Edmonton Police Service TECHNICAL REPORT January 2003 Submitted by: Officer Safety Unit Edmonton Police Service Edmonton Alberta Canada NOTE: Further information NOTA: Pour de plus ample about this report can be renseignements veuillez obtained by calling the communiquer avec le CCRP CPRC information number au (613) 998-6343 (613) 998-6343 © HER MAJESTY THE QUEEN IN RIGHT OF CANADA (2002) © SA MAJESTÉ LA REINE DU CHEF DU CANADA (2002) as represented by the Solicitor General of Canada. -

Selected Police-Reported Crime and Calls for Service During the COVID-19 Pandemic, March 2020 to March 2021 Released at 8:30 A.M

Selected police-reported crime and calls for service during the COVID-19 pandemic, March 2020 to March 2021 Released at 8:30 a.m. Eastern time in The Daily, Tuesday, May 18, 2021 Police-reported data on selected types of crimes and calls for service during the COVID-19 pandemic from March 2020 to March 2021 are now available. Note to readers The Canadian Centre for Justice and Community Safety Statistics is conducting a special survey collection from a sample of police services across Canada to measure the impact of COVID-19 on selected types of crimes and on calls for service. Data will continue to be collected monthly until December 2021 and to be reported regularly. This is the fifth release of this special data collection by Statistics Canada. Previously published data may have been revised. For this reference period, 19 police services provided data on a voluntary basis. These police services are the Calgary Police Service, Edmonton Police Service, Halton Regional Police Service, Kennebecasis Regional Police Force, London Police Service, Montréal Police Service, Ontario Provincial Police, Ottawa Police Service, Regina Police Service, Royal Canadian Mounted Police (RCMP), Royal Newfoundland Constabulary, Saskatoon Police Service, Sûreté du Québec, Toronto Police Service, Vancouver Police Department, Victoria Police Department, Waterloo Regional Police Service, Winnipeg Police Service, and York Regional Police. Police services that responded to this survey serve more than two-thirds (71%) of the Canadian population. Although the Edmonton Police Service, Montréal Police Service, RCMP, Sûreté du Québec and Winnipeg Police Service were unable to provide data on calls for service, the police services that did provide these data serve one-third (32%) of the Canadian population. -

TOBACCO WORLD RETAIL PRICES (Ovor 5,000 Retail PI-ICM)

THE CIGAR AND THE TOBACCO WORLD THE POPULAR JOURNAL TOBACCO OVER 40 YEARS OF TRADE USEFULNESS WORLD The Subscription includes : TOBACCO WORLD RETAIL PRICES (Ovor 5,000 Retail PI-ICM). RETAIL PRICES THE TOBACCO WORLD ANNUAL (Containing a word of Trad* Brand*—with Nam* and Addrau In each cms*). Membership of: TOBACCO WORLD SERVICE JUNE 1935 (With Pott Fnta raplUa In all Trad* difficult!**). The Cigar & Tobacco World HIYWOOO A COMPANY LTD. Dmrr How*, Kin—U 3tr*M, Ontry Una, London, W.C1 trantfc OACM f Baadmur. •trmlnfhtn, Uteanar. ToWfTHM i OffUlfrunt, Phono, LonAon. •Phono I TomaU far M1J Published by THE CIGAR & TOBACCO WORLD HEYWOOD & CO., LTD. DRURY HOUSE, RUSSELL STREET, DRURY LANE, LONDON, W.C.2 Branch Offices: MANCHESTER, BIRMINGHAM, LEICESTER Talagrarm : "Organigram. Phono, London." Phono : Tampla Bar MZJ '' Inar) "TOBACCO WORLD" RETAIL PRICES 1935 Authorised retail prices of Tobaccos, Cigarettes, Fancy Goods, and Tobacconists' Sundries. ABDULLA & Co., Ltd. (\BDULD^ 173 New Bond Street, W.l. Telephone; Bishopsgnte 4815, Authorised Current Retail Prices. Turkish Cigarettes. Price per Box of 100 50 25 20 10 No. 5 14/6 7/4 3/8 — 1/6 No. 5 .. .. Rose Tipped .. 28/9 14/6 7/3 — 3/- No. 11 11/8 5/11 3/- - 1/3 No. II .. .. Gold Tipped .. 13/S 6/9 3/5 - No. 21 10/8 5/5 2/9 — 1/1 Turkish Coronet No. 1 7/6 3/9 1/10J 1/6 9d. No. "X" — 3/- 1/6 — — '.i^Sr*** •* "~)" "Salisbury" — 2/6 — 1/- 6d. Egyptian Cigarettes. No. 14 Special 12/5 6/3 3/2 — — No. -

Pathways to Resilience: Formal Service and Informal Support Use Patterns Among Youth in Challenging Social Ecologies

Pathways to Resilience: Formal Service and Informal Support Use Patterns among Youth in Challenging Social Ecologies IDRC Project Number: 104518 Final technical report February 2015 Country/Region: China, Colombia, South Africa Prepared by: Tian Guoxiu, Faculty of Politics and Law Capital Normal University Beijing, China [email protected] Alexandra Restrepo Henao, National School of Public Health Universidad de Anioquia Medellín, Colombia [email protected] Linda Theron, Optentia Research Focus Area Faculty of Humanities North-West University, Hendrik van Eck Boulevard, Vanderbijlpark, South Africa [email protected] Madine VanderPlaat Dept. of Sociology & Criminology Saint Mary’s University Halifax, Canada This report is presented as received from project recipient(s). It comprises the reports by the P.I.s from China, Colombia, and South Africa, some of which have been edited for clarity. The report also includes content from students involved in the project, which appears with their consent. The authors gratefully acknowledge the editorial support of Aliya Jamal (RA at the Resilience Research Centre). It has not been subjected to peer review or other review processes. Keywords: resilience, youth, China, Colombia, South Africa, community advisory panel, social ecology, formal service ecology, formal supports, informal supports, mixed methods Table of Contents Tribute to Luis Fernando Duque .................................................................................................. 1! 1! Research problem .................................................................................................................. -

Ash Park on Tobacco & Transformation

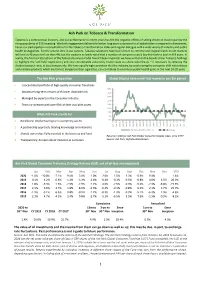

Ash Park on Tobacco & Transformation Tobacco is a controversial industry, and our performance in recent years has felt the negative effects of selling driven at least in part by the rising popularity of ESG investing. We think engagement delivers far better long-term outcomes for all stakeholders compared to divestment, hence our participation in consultations for the Tobacco Transformation Index and regular dialogue with a wide variety of industry and public health protagonists. For the second time in our careers, Tobacco valuations have been driven to extreme and illogical levels: credit markets will lend at 40 years for less than 4%, but the equity is so lowly-rated that a number of companies could buy themselves back in 8-9 years. In reality, the financial attractions of the Tobacco business model haven’t been impaired; we have written to the boards of our Tobacco holdings to highlight the ‘self-help’ opportunity and very considerable value they could create via share repurchases – if necessary by rebasing the dividend payout ratio, at least temporarily. We have equally high conviction that the industry, by accelerating the consumer shift into tobacco and nicotine products which are far less dangerous than cigarettes, can contribute to enormous public health gains in the next 10-20 years. The Ash Park proposition Global Staples have never lost money in any 5yr period • Concentrated portfolio of high-quality consumer franchises 40% • Attractive long-term returns with lower downside risk 35% 30% • Managed by experts in the Consumer industry 25% • Team co-invested with over 90% of their available assets 20% 15% 10% What Ash Park stands for 5% 1. -

Arbutus Greenway Evaluation

ARBUTUS GREENWAY EVALUATION 2019 Report to Stakeholders INTRODUCTION Our postal code may be a better predictor of our health than our genetic code. The design of our neighbourhoods influences how we move, feel, and interact, in turn impacting our chances of experiencing poor health outcomes like heart disease, diabetes, and cancer. Canada has committed to spending more than $180 billion on infrastructure over 12 years. How will these investments impact our health and well-being? Who stands to benefit, and how? The Active Aging Research Team (AART) from the Centre for Hip Health and Mobility is conducting research that aims to characterize the social and health impacts of the Arbutus Greenway development. AART will assess who, what, when, where, why, or why not people in surrounding neighbourhoods (or elsewhere) use the Arbutus Greenway. They seek to understand whether the Arbutus Greenway contributes to peoples’ health and social interactions. AART is also a part of a CIHR funded research team - INTErventions, Research, and Action in Cities Team (INTERACT). INTERACT is a national collaboration of scientists, urban planners, and public health decision-makers with a common vision of healthy, equitable, and sustainable cities by design. In partnership with cities and citizens, we harness big data to deliver timely public health intelligence on the influence of the built environment on health, well-being, and social inequities. Initially launching in four cities across Canada – Victoria, Vancouver, Saskatoon, and Montreal – INTERACT will evaluate the health impact of real world urban form interventions. The Arbutus Greenway is the study focus for the Vancouver site of INTERACT.