LGBT Asylum Seekers in Sweden Conceptualising Queer Migration Beyond the Concept of “Safe Third Country”

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Gender Reassignment Surgery Policy Number: PG0311 ADVANTAGE | ELITE | HMO Last Review: 07/01/2021

Gender Reassignment Surgery Policy Number: PG0311 ADVANTAGE | ELITE | HMO Last Review: 07/01/2021 INDIVIDUAL MARKETPLACE | PROMEDICA MEDICARE PLAN | PPO GUIDELINES This policy does not certify benefits or authorization of benefits, which is designated by each individual policyholder terms, conditions, exclusions and limitations contract. It does not constitute a contract or guarantee regarding coverage or reimbursement/payment. Self-Insured group specific policy will supersede this general policy when group supplementary plan document or individual plan decision directs otherwise. Paramount applies coding edits to all medical claims through coding logic software to evaluate the accuracy and adherence to accepted national standards. This medical policy is solely for guiding medical necessity and explaining correct procedure reporting used to assist in making coverage decisions and administering benefits. SCOPE X Professional X Facility DESCRIPTION Transgender is a broad term that can be used to describe people whose gender identity is different from the gender they were thought to be when they were born. Gender dysphoria (GD) or gender identity disorder is defined as evidence of a strong and persistent cross-gender identification, which is the desire to be, or the insistence that one is of the other gender. Persons with this disorder experience a sense of discomfort and inappropriateness regarding their anatomic or genetic sexual characteristics. Individuals with GD have persistent feelings of gender discomfort and inappropriateness of their anatomical sex, strong and ongoing cross-gender identification, and a desire to live and be accepted as a member of the opposite sex. Gender Dysphoria (GD) is defined by the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders - Fifth Edition, DSM-5™ as a condition characterized by the "distress that may accompany the incongruence between one’s experienced or expressed gender and one’s assigned gender" also known as “natal gender”, which is the individual’s sex determined at birth. -

Elections at the Conference

36th European Conference of the International Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Trans and Intersex Association 18th ILGA-Europe conference Riga, 9 October – 11 October 2014 Organised in association with the Rīga organising committee ILGA-Europe Conference 2014 ELECTIONS AT THE CONFERENCE This document consists of the following information: 1. Presentation of the candidates to ILGA-Europe and ILGA Boards 2. Explanation of the election procedures for ILGA-Europe Board 3. Explanation of the election procedures for ILGA Board 4. Presentation of the candidate for the host venue for the 2016 ILGA-Europe conference 1. Candidates to ILGA-Europe and ILGA Boards Below is the list of candidates for the ILGA-Europe Board. Their nominations and election statements are attached at the end of this document. The election procedures are explained in the separate document ‘Guide to elections’ included in this mailing. Name Organisation Country Identifying as Agata Chaber Kampania Przeciw Homofobii Poland Gender – Campaign Against neutral / Homophobia (KPH) trans Magali Deval Commission LGBT – Europe France F Ecologie – Les Verts (LGBT committee – French Greens) ELECTIONS AT THE CONFERENCE – THIRD MAILING (Riga) Darienne UNISON National LGBT UK F Flemington Committee Costa Gavrielides Accept – LGBT Cyprus Cyprus M Joyce Hamilton COC Netherland Netherlands F Henrik Hynkemejer LGBT Denmark, The Danish Denmark M National Organisation for Gay Men, Lesbians, Bisexuals and Transgender persons. Konstantina OLKE (Lesbian and Gay Greece F Kosmidou Community of Greece) Brian Sheehan Gay & Lesbian Equality Ireland M Network (GLEN) Below is the list of candidates for the ILGA Board. Their nominations and election statements are attached at the end of this document. -

INCORPORATING TRANSGENDER VOICES INTO the DEVELOPMENT of PRISON POLICIES Kayleigh Smith

15 Hous. J. Health L. & Policy 253 Copyright © 2015 Kayleigh Smith Houston Journal of Health Law & Policy FREE TO BE ME: INCORPORATING TRANSGENDER VOICES INTO THE DEVELOPMENT OF PRISON POLICIES Kayleigh Smith I. INTRODUCTION In the summer of 2013, Netflix aired its groundbreaking series about a women’s federal penitentiary, Orange is the New Black. One of the series’ most beloved characters is Sophia, a transgender woman who committed credit card fraud in order to pay for her sex reassignment surgeries.1 In one of the most poignant scenes of the entire first season, Sophia is in the clinic trying to regain access to the hormones she needs to maintain her physical transformation, and she tells the doctor with tears in her eyes, “I need my dosage. I have given five years, eighty thousand dollars, and my freedom for this. I am finally who I am supposed to be. I can’t go back.”2 Sophia is a fictional character, but her story is similar to the thousands of transgender individuals living within the United States prison system.3 In addition to a severe lack of physical and mental healthcare, many transgender individuals are harassed and assaulted, creating an environment that leads to suicide and self- 1 Orange is the New Black: Lesbian Request Denied (Netflix streamed July 11, 2013). Transgender actress Laverne Cox plays Sophia on Orange is the New Black. Cox’s rise to fame has given her a platform to speak about transgender rights in the mainstream media. See Saeed Jones, Laverne Cox is the Woman We Have Been Waiting For, BUZZFEED (Mar. -

Rights of Transgender Adolescents to Sex Reassignment Treatment

THE DOCTOR WON'T SEE YOU NOW: RIGHTS OF TRANSGENDER ADOLESCENTS TO SEX REASSIGNMENT TREATMENT SONJA SHIELD* I. INTRODUCTION .................................................................................................... 362 H . DEFINITIO NS ........................................................................................................ 365 III. THE HARMS SUFFERED BY TRANSGENDER ADOLESCENTS CREATE A NEED FOR EARLY TRANSITION .................................................... 367 A. DISCRIMINATION AND HARASSMENT FACED BY TRANSGENDER YOUTH .............. 367 1. School-based violence and harassment............................................................. 368 2. Discriminationby parents and thefoster care system ....................................... 372 3. Homelessness, poverty, and criminalization...................................................... 375 B. PHYSICAL AND MENTAL EFFECTS OF DELAYED TRANSITION ............................... 378 1. Puberty and physical changes ........................................................................... 378 2. M ental health issues ........................................................................................... 382 IV. MEDICAL AND PSYCHIATRIC RESPONSES TO TRANSGENDER PEOPLE ........................................................................................ 385 A. GENDER IDENTITY DISORDER TREATMENT ........................................................... 386 B. FEARS OF POST-TREATMENT REGRET ................................................................... -

Sex Reassignment Surgery Is Defined As a Surgery Performed for the Treatment of a Confirmed Gender Dysphoria Diagnosis

Coverage of any medical intervention discussed in a WellFirst Health medical policy is subject to the limitations and exclusions outlined in the member's benefit certificate or policy and applicable state and/or federal laws. Medicare Advantage Sex Reassignment (Sex Transformation) Surgery MP9465 This policy is specific to the Medicare Advantage plan. Covered Service: Yes Services described in this policy are not restricted to those Certificates which contain the Sex Transformation Surgery Rider Prior Authorization Required: Yes Additional The medical policy criteria herein govern coverage Information: determinations for Sex Reassignment (Sex Transformation) Surgeries. Authorization may only be granted if the member is an active participant in a recognized gender identity treatment program. Sex Reassignment Surgery is defined as a surgery performed for the treatment of a confirmed gender dysphoria diagnosis. WellFirst Health Medical Policy: 1.0 All Sex Reassignment Surgeries require prior authorization through the Health Services Division and are considered medically appropriate when ALL of the following are met: 1.1 Letter(s) of referral for surgery from the individual’s qualified mental health professional competent in the assessment and treatment of gender dysphoria, which includes: 1.1.1 Letter of referral should include ALL the following information: 1.1.1.1 Member’s general identifying characteristics; AND 1.1.1.2 Results of the client’s psychological assessment, including any diagnoses; AND 1.1.1.3 The duration of the mental health professional’s relationship with the client, including the type of evaluation and therapy or counseling to date; AND All WellFirst Health products and services are provided by subsidiaries of SSM Health Care Corporation, including, but not limited to, SSM Health Insurance Company and SSM Health Plan. -

Bibliography

BIbLIOGRAPHY Abbott, K., Ellis, S., & Abbott, R. (2015). “We don’t get into all that”: An analysis of how teachers uphold heteronormative sex and relationship education. Journal of Homosexuality, 62(12), 1638–1659. Act of 17 July 1998 no. 61 relating to Primary and Secondary Education and Training (the Education Act). Retrieved from https://www.european-agency. org/sites/default/files/Education_Act_Norway.pdf Act on Registered Partnership. (2001). Retrieved from http://www.finlex.fi/fi/ laki/kaannokset/2001/en20010950.pdf Act on Registered Partnership No. 87/1996. Retrieved from http://www.althingi. is/altext/120/s/1182.html Agamben, G. (1999). Potentialities (D. Heller-Roazen, Trans.). Stanford: Stanford University Press. Alanko, K. (2013). Hur mår HBTIQungdomar i Finland? Helsinki: Finnish Youth Research Society. Finnish Youth Research Network. Retrieved from http:// www.nuorisotutkimusseura.fi/images/julkaisuja/hbtiq_unga.pdf Aleman, G. (2005). Constructing gay performances: Regulating gay youth in a “gay friendly” high school. In B. K. Alexander, G. L. Anderson, & B. P. Gallegos (Eds.), Performance theories in education: Power, pedagogy, and the politics of identity (pp. 149–171). Mahwah: Erlbaum. Allan, J. (1999). Actively seeking inclusion: Pupils with special needs in mainstream schools. London: Falmer. Allan, J. (2008). Rethinking inclusion: The philosophers of difference in practice. Dordrecht: Springer. © The Author(s) 2017 211 J.I. Kjaran, Constructing Sexualities and Gendered Bodies in School Spaces, DOI 10.1057/978-1-137-53333-3 212 BibliOgraphy Allen, D. J., & Oleson, T. (1999). Shame and internalized homophobia in gay men. Journal of Homosexuality, 37(3), 33–43. Allen, L. (2007). Denying the sexual subject: Schools’ regulation of student sexu- ality. -

LGBT Student Guide for Education Abroad Table of Contents Why This Guide Was Made: a Note from the Author 2

LGBT Student Guide for Education Abroad Table of Contents Why This Guide Was Made: A Note From The Author 2 General Things to Consider 3 Global Resources 5 Internet Resources 5 Print Resources 5 Region and Country Narratives and Resources 6 Africa 6 Ghana 7 Pacifica 8 Australia 8 Asia 9 China 9 India 10 Japan 11 South Korea 12 Malaysia 13 Europe 14 Czech Republic 14 Denmark 15 France 16 Germany 17 Greece 18 Italy 19 Russia 20 Slovakia 21 Spain 22 Sweden 23 United Kingdom 24 The Americas 25 Argentina 25 Bolivia 26 Brazil 27 Canada 28 Costa Rica 29 Honduras 30 Mexico 31 Panama 32 Peru 33 1 Why This Guide Was Made A Note From The Author Kristen Shalosky In order to tell you how and why this guide was made, I must first give you some background on myself. I attended USF as an undergraduate student of the College of Business and the Honors College from Fall 2006 to Spring 2010. During that time, I became very involved with the LGBT (Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual and Transgender) advocacy movements on campus, including being President of the PRIDE Alliance for a year. When I was told that the Education Abroad department was looking for an Honors Thesis candidate to help find ways to make the department and its programs more LGBT-friendly, it seemed like a natural choice. As I conducted my research, I realized that there are some things that LGBT students need to consider before traveling abroad that other students don’t. Coming out as an LGBT student abroad can be much different than in the U.S.; in extreme cases, the results of not knowing cultural or legal standards can be violence or imprisonment. -

BSC7.02 Gender Reassignment Surgery Original Policy Date: June 28, 2013 Effective Date: April 1, 2021 Section: 7.0 Surgery Page: Page 1 of 26

Medical Policy BSC7.02 Gender Reassignment Surgery Original Policy Date: June 28, 2013 Effective Date: April 1, 2021 Section: 7.0 Surgery Page: Page 1 of 26 Policy Statement Note: This policy only applies to (self-funded) Administrative Service Organizations (ASO). For (fully-insured) commercial lines of business, the nonprofit professional society Standards of Care developed by the World Professional Association for Transgender Health (WPATH) will be used as guidelines when making determinations in accordance with SB 855. Gender reassignment surgery for confirmed gender dysphoria may be considered medically necessary when all of the following criteria are met: I. The individual is age 18 or older (the legal age of majority in the United States of America); see Policy Guidelines for possible exceptions. II. The individual has a documented DSM-5 diagnosis of gender dysphoria including all of the following: A. A strong desire to be treated as a gender other than that assigned. This may be accompanied by the desire to make their body as congruent as possible with the preferred gender through hormone therapy and/or gender reassignment surgery B. Disorder is not a symptom of another mental disorder (e.g., schizophrenia) C. Disorder causes clinically significant distress or impairment in social, occupational, or other important areas of functioning III. If significant medical or mental health concerns are present, they must be reasonably well-controlled. If the individual is diagnosed with severe psychiatric disorders and impaired reality testing (e.g., psychotic episodes, bipolar disorder, dissociative identity disorder, borderline personality disorder) an effort must be made to improve these conditions with psychotropic medications and/or psychotherapy before surgery is contemplated. -

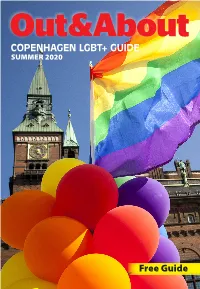

COPENHAGEN LGBT+ GUIDE Free Guide

COPENHAGEN LGBT+ GUIDE SUMMER 2020 Free Guide Out&About Copenhagen LGBT+ Guide * Summer 2020 1 Welcome to Copenhagen A city with room for diversity Copenhagen is a vibrant, liveable city Since the very first homosexual with a colourful cultural life. We have marriage in Copenhagen in 1989, our highly developed public transporta- city has been a pioneer in the field of tion, a bicycle infrastructure second LGBTI+ rights. In 2019 we adopted a to none and our harbour is so clean, new overall LGBTI+ policy to ensure that you can swim in it. For those – that the municipality meets LGBTI+ and many other reasons – Copen- persons with respect, equality, dia- hagen is continuously rated among logue and confidence. This makes the most liveable cities in the world. Copenhagen the first Danish mu- Another vital reason for our live- nicipality with an overall policy in ability is Copenhagen’s famous this area. open-mindedness and tolerance. In Copenhagen, we are very proud No matter your colour, sexual orien- of the city’s social diversity and tol- tation, religion or gender identity, erance. And we actively protect and Copenhagen welcomes you. promote the freedom of expression 2020 has been a very exceptional for all minority groups. year worldwide including Denmark As Denmark slowly begins to open and Copenhagen due to the Covid-19 the borders after the corona lock pandemic. I look forward to getting down, we look forward to welcom- our city back to its usual vibrant self ing visitors from all over the world with both local and international yet again. -

Priority Health Gender Dysphoria Benefits Outline

The GVSU medical plans provide coverage for the treatment of gender dysphoria. The following outline details the definition of coverage and the criteria that our medical plan administrator, Priority Health, applies in providing this benefit. If you have specific questions you can contact our care manager at Priority Health, Christine, RN, BSN, CDE at: [email protected] or 800.998.1037 ext 68887. PRIORITY HEALTH GENDER DYSPHORIA BENEFITS OUTLINE GENDER DYSPHORIA, NON-SURGICAL TREATMENT I. POLICY/CRITERIA A. The following non-surgical services are a covered benefit for gender dysphoria; limitations may apply: 1. Mental health services as defined in plan coverage documents and policies. 2. Hormone therapy when all of the following criteria are met: a. Evaluation and at least three months of mental health therapy for the diagnosis of gender dysphoria by a licensed mental health practitioner. b. Optimal management of any comorbid medical or mental health conditions. c. Member (or parent/guardian) has the capacity to make fully informed decisions and consent to treatment. d. Laboratory testing to monitor hormone therapy is a covered benefit. e. Hormone therapy obtained from a pharmacy is subject to the pharmaceutical cost share/copay of the member’s contract. f. Member’s contract must include a prescription drug rider. 3. Hormonal suppression of puberty is a covered benefit when all of the following are met: a. Onset of puberty to at least Tanner Stage 2 b. A long-lasting and intense pattern of gender nonconformity or gender dysphoria (whether suppressed or expressed) c. Gender dysphoria worsened with the onset of puberty d. -

Full Versions of Final Reports for Nlos

Legal Study on Homophobia and Discrimination on Grounds of Sexual Orientation and Gender Identity Denmark January 2014 Update Authors of the 2014 Update: Mandana Zarrehparvar Franet contractor: Danish Institute for Human Rights Authors of the 2010 Update: Christoffer Badse Martin Futtrup Author of the 2008 report: Birgitte Kofod Olsen DISCLAIMER: This document was commissioned under contract as background material for comparative analysis by the European Union Agency for Fundamental Rights (FRA) for the project ‘Protection against discrimination on grounds of sexual orientation, gender identity and sex characteristics in the EU, Comparative legal analysis, Update 2015’. The information and views contained in the document do not necessarily reflect the views or the official position of the FRA. The document is made publicly available for transparency and information purposes only and does not constitute legal advice or legal opinion. Contents Executive summary ................................................................................................................... 1 1. Implementation of Employment Directive 2000/78/EC .............................................................. 9 1.1 Equality Bodies ............................................................................................................................ 10 1.2 Non-Governmental Organisations ...................................................................................................... 12 2. Freedom of movement .......................................................................................................... -

EPATH 2015 Book of Abstracts

First biennial conference of the TRANSGENDER HEALTH CARE IN EUROPE BOOK OF ABSTRACTS MARCH 12-14, 2015 GHENT, BELGIUM EPATH Biennial Conference “Transgender Health Care in Europe” March 12 – 14, 2015, Ghent, Belgium OVERVIEW ORAL PRESENTATIONS .................................................................................................... 8 KEYNOTE LECTURES ............................................................................................................ 8 Plenary Session I: Henriette Delemarre Memorial Lecture (March 12th, 2015, 13:45 – 14:30) .......... 8 1. Youth with gender incongruence: culture and future ............................................................ 8 Public Plenary Session: Human Rights and Health Care for Trans People in Europe (March 12th, 2015, doors open at 18:00) ................................................................................................................ 8 1. Caring for transgender adolescents: future perspectives ........................................................ 8 2. Fertility options for trans people............................................................................................... 9 3. Human rights for trans people: taking stock of where we are in Europe ............................. 9 STREAM SESSIONS I (T HURSDAY MARCH 12, 2015, 14:00 – 15:30) ......................................... 10 STREAM MENTAL HEALTH ...................................................................................................................... 10 Session 1: Epidemiology,