The Forty Year Crisis Berlin

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Allen Dulles - Wikipedia

8/6/2020 Allen Dulles - Wikipedia Allen Dulles Allen Welsh Dulles (/ˈdʌləs/; April 7, 1893 – January 29, 1969) was an American diplomat and lawyer who became the Allen Dulles first civilian Director of Central Intelligence (DCI), and its longest-serving director to date. As head of the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) during the early Cold War, he oversaw the 1953 Iranian coup d'état, the 1954 Guatemalan coup d'état, the Lockheed U-2 aircraft program, the Project MKUltra mind control program and the Bay of Pigs Invasion. He was dismissed by John F. Kennedy over the latter fiasco. Dulles was one of the members of the Warren Commission investigating the assassination of John F. Kennedy. Between his stints of government service, Dulles was a corporate lawyer and partner at Sullivan & Cromwell. His older brother, John Foster Dulles, was the Secretary of State during the Eisenhower Administration and is the namesake of Dulles Airport.[1] Director of Central Intelligence In office Contents February 26, 1953 – November 29, 1961 Early life and family President Dwight Eisenhower John F. Kennedy Early career OSS posting to Bern, Switzerland in World War II Deputy Charles P. Cabell Preceded by Walter B. Smith CIA career Coup in Iran Succeeded by John McCone Coup in Guatemala Deputy Director of Central Intelligence Bay of Pigs In office Dismissal August 23, 1951 – February 26, 1953 Later life President Harry S. Truman Dwight Eisenhower Fictional portrayals Preceded by William H. Jackson Publications Articles Succeeded by Charles P. Cabell Book reviews Deputy Director of Central Intelligence Books for Plans Books edited In office Book contributions January 4, 1951 – August 23, 1951 President Harry S. -

CHAPTER 2 the Period of the Weimar Republic Is Divided Into Three

CHAPTER 2 BERLIN DURING THE WEIMAR REPUBLIC The period of the Weimar Republic is divided into three periods, 1918 to 1923, 1924 to 1929, and 1930 to 1933, but we usually associate Weimar culture with the middle period when the post WWI revolutionary chaos had settled down and before the Nazis made their aggressive claim for power. This second period of the Weimar Republic after 1924 is considered Berlin’s most prosperous period, and is often referred to as the “Golden Twenties”. They were exciting and extremely vibrant years in the history of Berlin, as a sophisticated and innovative culture developed including architecture and design, literature, film, painting, music, criticism, philosophy, psychology, and fashion. For a short time Berlin seemed to be the center of European creativity where cinema was making huge technical and artistic strides. Like a firework display, Berlin was burning off all its energy in those five short years. A literary walk through Berlin during the Weimar period begins at the Kurfürstendamm, Berlin’s new part that came into its prime during the Weimar period. Large new movie theaters were built across from the Kaiser Wilhelm Memorial church, the Capitol und Ufa-Palast, and many new cafés made the Kurfürstendamm into Berlin’s avant-garde boulevard. Max Reinhardt’s theater became a major attraction along with bars, nightclubs, wine restaurants, Russian tearooms and dance halls, providing a hangout for Weimar’s young writers. But Berlin’s Kurfürstendamm is mostly famous for its revered literary cafés, Kranzler, Schwanecke and the most renowned, the Romanische Café in the impressive looking Romanische Haus across from the Memorial church. -

THE CYPRUS GREEN LINE – BRIDGING the GAP by Zachariasantoniades the Cyprus Buffer Zone Divides the Old City of Nicosia Into North and South • Abstract

Ch llenges for a new future THE CYPRUS GREEN LINE – BRIDGING GAP By Zacharias Antoniades The Cyprus buffer zone divides the old city of Nicosia into North and South • Abstract ............................... 06 • Introduction: Brief story of Nicosia ............................... 08 • "Borders are the scars of history". ............................... 14 • Lessons from Berlin ............................... 20 • Is a border purely a point of division, or can it also become one of contact between two ............................... 26 different cultures? Contents • “Third-spaces create space for envisioning ............................... 32 changes in divided cities” • The appropriate program for the appropriate ............................... 36 building. • Conclusion ............................... 42 • Bibliography ............................... 45 • Websites ............................... 47 3 4 Abstract Since 1974, Cyprus, the country that I call home has been divided in two parts, separating the two major ethnicities of the island (Greeks and Turks). In between these north and south parts lies the well-known Cyprus Buffer zone that to this day expresses the realities of the armed conflict that took place there four decades ago. This buffer zone rep- resents the lack of communication and mistrust that exists between the two ‘rival’ sides. As a Cypriot designer I felt the need to come up with an appropri- ate project that will bring people closer together, giving them the chance to communicate, debate, exchange knowledge and views and generally understand the needs of each side leading to a better and smoother social and cultural blend thus making it easier for the people to digest any future plans of total reunification. In order to get inspiration and a better understanding of how to deal with such situations I examined borders and their evolvement at differ- ent scales and contexts, but also looking at various peace-promoting projects in conflict zones. -

Walls and Fences: a Journey Through History and Economics

A Service of Leibniz-Informationszentrum econstor Wirtschaft Leibniz Information Centre Make Your Publications Visible. zbw for Economics Vernon, Victoria; Zimmermann, Klaus F. Working Paper Walls and Fences: A Journey Through History and Economics GLO Discussion Paper, No. 330 Provided in Cooperation with: Global Labor Organization (GLO) Suggested Citation: Vernon, Victoria; Zimmermann, Klaus F. (2019) : Walls and Fences: A Journey Through History and Economics, GLO Discussion Paper, No. 330, Global Labor Organization (GLO), Essen This Version is available at: http://hdl.handle.net/10419/193640 Standard-Nutzungsbedingungen: Terms of use: Die Dokumente auf EconStor dürfen zu eigenen wissenschaftlichen Documents in EconStor may be saved and copied for your Zwecken und zum Privatgebrauch gespeichert und kopiert werden. personal and scholarly purposes. Sie dürfen die Dokumente nicht für öffentliche oder kommerzielle You are not to copy documents for public or commercial Zwecke vervielfältigen, öffentlich ausstellen, öffentlich zugänglich purposes, to exhibit the documents publicly, to make them machen, vertreiben oder anderweitig nutzen. publicly available on the internet, or to distribute or otherwise use the documents in public. Sofern die Verfasser die Dokumente unter Open-Content-Lizenzen (insbesondere CC-Lizenzen) zur Verfügung gestellt haben sollten, If the documents have been made available under an Open gelten abweichend von diesen Nutzungsbedingungen die in der dort Content Licence (especially Creative Commons Licences), you genannten Lizenz gewährten Nutzungsrechte. may exercise further usage rights as specified in the indicated licence. www.econstor.eu Walls and Fences: A Journey Through History and Economics* Victoria Vernon State University of New York and GLO; [email protected] Klaus F. Zimmermann UNU-MERIT, CEPR and GLO; [email protected] March 2019 Abstract Throughout history, border walls and fences have been built for defense, to claim land, to signal power, and to control migration. -

John F. Kennedy and Berlin Nicholas Labinski Marquette University

Marquette University e-Publications@Marquette Master's Theses (2009 -) Dissertations, Theses, and Professional Projects Evolution of a President: John F. Kennedy and Berlin Nicholas Labinski Marquette University Recommended Citation Labinski, Nicholas, "Evolution of a President: John F. Kennedy and Berlin" (2011). Master's Theses (2009 -). Paper 104. http://epublications.marquette.edu/theses_open/104 EVOLUTION OF A PRESIDENT: JOHN F. KENNEDYAND BERLIN by Nicholas Labinski A Thesis submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate School, Marquette University, in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts Milwaukee, Wisconsin August 2011 ABSTRACT EVOLUTION OF A PRESIDENT: JOHN F. KENNEDYAND BERLIN Nicholas Labinski Marquette University, 2011 This paper examines John F. Kennedy’s rhetoric concerning the Berlin Crisis (1961-1963). Three major speeches are analyzed: Kennedy’s Radio and Television Report to the American People on the Berlin Crisis , the Address at Rudolph Wilde Platz and the Address at the Free University. The study interrogates the rhetorical strategies implemented by Kennedy in confronting Khrushchev over the explosive situation in Berlin. The paper attempts to answer the following research questions: What is the historical context that helped frame the rhetorical situation Kennedy faced? What rhetorical strategies and tactics did Kennedy employ in these speeches? How might Kennedy's speeches extend our understanding of presidential public address? What is the impact of Kennedy's speeches on U.S. German relations and the development of U.S. and German Policy? What implications might these speeches have for the study and execution of presidential power and international diplomacy? Using a historical-rhetorical methodology that incorporates the historical circumstances surrounding the crisis into the analysis, this examination of Kennedy’s rhetoric reveals his evolution concerning Berlin and his Cold War strategy. -

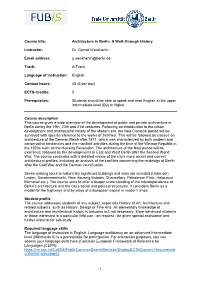

Architecture in Berlin. a Walk Through History Instructor

Course title: Architecture in Berlin. A Walk through History Instructor: Dr. Gernot Weckherlin Email address: [email protected] Track: A-Track Language of instruction: English Contact hours: 48 (6 per day) ECTS-Credits: 5 Prerequisites: Students should be able to speak and read English at the upper intermediate level (B2) or higher. Course description This course gives a wide overview of the development of public and private architecture in Berlin during the 19th, 20th and 21st centuries. Following an introduction to the urban development and architectural history of the Modern era, the Neo-Classical period will be surveyed with special reference to the works of Schinkel. This will be followed by classes on architecture of the German Reich after 1871, which was characterized by both modern and conservative tendencies and the manifold activities during the time of the Weimar Republic in the 1920s such as the Housing Revolution. The architecture of the Nazi period will be examined, followed by the developments in East and West Berlin after the Second World War. The course concludes with a detailed review of the city’s more recent and current architectural profiles, including an analysis of the conflicts concerning the re-design of Berlin after the Cold War and the German reunification. Seven walking tours to historically significant buildings and sites are included (Unter den Linden, Gendarmenmarkt, New Housing Estates, Chancellory, Potsdamer Platz, Holocaust Memorial etc.). The course aims to offer a deeper understanding of the interdependence of Berlin’s architecture and the city’s social and political structures. It considers Berlin as a model for the highways and by-ways of a European capital in modern times. -

Aftermath: Accounting for the Holocaust in the Czech Republic

Aftermath: Accounting for the Holocaust in the Czech Republic Krista Hegburg Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences COLUMBIA UNIVERISTY 2013 © 2013 Krista Hegburg All rights reserved Abstract Aftermath: Accounting for the Holocaust in the Czech Republic Krista Hegburg Reparations are often theorized in the vein of juridical accountability: victims of historical injustices call states to account for their suffering; states, in a gesture that marks a restoration of the rule of law, acknowledge and repair these wrongs via financial compensation. But as reparations projects intersect with a consolidation of liberalism that, in the postsocialist Czech Republic, increasingly hinges on a politics of recognition, reparations concomitantly interpellate minority subjects as such, instantiating their precarious inclusion into the body po litic in a way that vexes the both the historical justice and contemporary recognition reparatory projects seek. This dissertation analyzes claims made by Czech Romani Holocaust survivors in reparations programs, the social work apparatus through which they pursued their claims, and the often contradictory demands of the complex legal structures that have governed eligibility for reparations since the immediate aftermath of the war, and argues for an ethnographic examination of the forms of discrepant reciprocity and commensuration that underpin, and often foreclose, attempts to account for the Holocaust in contemporary Europe. Table of Contents Acknowledgments ii Introduction 1 Chapter 1 18 Recognitions Chapter 2 74 The Veracious Voice: Gypsiology, Historiography, and the Unknown Holocaust Chapter 3 121 Reparations Politics, Czech Style: Law, the Camp, Sovereignty Chapter 4 176 “The Law is Such as It Is” Conclusion 198 The Obligation to Receive Bibliography 202 Appendix I 221 i Acknowledgments I have acquired many debts over the course of researching and writing this dissertation. -

THE BERLIN-KOREA PARALLEL: BERLIN and AMERICAN NATIONAL SECURITY in LIGHT of the KOREAN WAR Author(S): DAVID G

THE BERLIN-KOREA PARALLEL: BERLIN AND AMERICAN NATIONAL SECURITY IN LIGHT OF THE KOREAN WAR Author(s): DAVID G. COLEMAN Reviewed work(s): Source: Australasian Journal of American Studies, Vol. 18, No. 1 (July, 1999), pp. 19-41 Published by: Australia and New Zealand American Studies Association Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/41018739 . Accessed: 18/09/2012 14:16 Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at . http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp . JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. Australia and New Zealand American Studies Association is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Australasian Journal of American Studies. http://www.jstor.org AUSTRALASIAN JOURNALOF AMERICAN STUDIES 19 THE BERLIN-KOREA PARALLEL: BERLIN AND AMERICAN NATIONAL SECURITY IN LIGHT OF THE KOREAN WAR DAVID G. COLEMAN The Korean War had a profoundimpact on the ways in which American policymakersperceived the Cold War.Nowhere was thismore fact evident than in the case of Berlin. Despite the geographicalseparation between the two countries,policymakers became concernedwith what theyidentified as the 'Berlin-Koreaparallel.' Holding the Soviet Union responsible for North Korea's aggression,Washington believed that in NorthKorea's attackit was witnessing a new Sovietcapability that could give theUSSR a decisiveedge in the Cold War. -

Cooperation Between Intelligence and Security Systems of German

COOPERATION BETWEEN INTELLIGENCE AND SECURITY SYSTEMS OF GERMAN DEMOCRATIC REPUBLIC AND YUGOSLAVIA Dr. sc. Gordan Akrap Summary: Intelligence and security system of GDR and Yugoslavia, despite the fact that it might look strange, did not have significant level of cooperation. The main reason for that was a huge political and ideological difference on political level. Each of them had their own, “unique”, way to create socialist society under the leadership of Communist party in power. But, despite the fact that they did not had any significant cooperation, both of those systems were established and organised according Russian intelligence and security systems. Repression against their citizens was one of the main similarities between those two systems. Due to the existence of the documents in German BStU it is possible to research their relations in those time of Cold war conflict, and huge antagonism between NATO and WB. Keywords: GDR, DDR, BRD, FRG, Yugoslavia, SFRJ, intelligence and security systems, Stasi, UDB-a, SDB, SED, SKJ, communist party, repression . 1 INTRODUCTION ) 201 ) 2 (1 Constant conflicts of various imperialistic policies with the 2 - 1 aim of gaining political, military and economic superiority over the opponent marked, especially in Europe, marked last century. These conflicts led to two world wars that have caused enormous human and material destruction with strong short- and long-term consequences for the involved states. In Europe had happened also several low-intensity conflicts that have not led to the involvements (or in direct conflict) significant number of states. Therefore, effects of those conflicts had limited (political and territorial) consequences. -

The Foreign Service Journal, September 1980

When you’re going overseas, you have enough to worry about without worrying about your insurance,too. Moving overseas can be a very traumatic time if you Moving overseas is simplified by the AFSA-sponsored don’t have the proper insurance. The fact is, the government insurance program for AFSA members. Our insurance will be responsible for only $15,000 worth of your belongings. program will take care of most of your worries. If any of your personal valuables such as cameras, jewelry, With our program, you can purchase as much property furs and fine arts are destroyed, damaged or stolen, you insurance as you feel you need at only 75tf per $100, and it would receive not the replacement cost of the goods, but only covers you for the replacement cost of household furniture a portion of what you’d have to pay to replace them. and personal effects that are destroyed, damaged or stolen, Claims processes are another headache you shouldn’t with no depreciation. You can also insure your valuable have to worry about. The government claims process is articles on an agreed amount basis, without any limitation. usually lengthy and requires investigation and AFSA coverage is worldwide, whether on business or documentation. pleasure. Should you have a problem, we provide simple, If you limit yourself to the protection provided under the fast, efficient claims service that begins with a simple phone Claims Act, you will not have worldwide comprehensive call or letter, and ends with payment in either U.S. dollars personal liability insurance, complete theft coverage or or local currency. -

Timeline of the Cold War

Timeline of the Cold War 1945 Defeat of Germany and Japan February 4-11: Yalta Conference meeting of FDR, Churchill, Stalin - the 'Big Three' Soviet Union has control of Eastern Europe. The Cold War Begins May 8: VE Day - Victory in Europe. Germany surrenders to the Red Army in Berlin July: Potsdam Conference - Germany was officially partitioned into four zones of occupation. August 6: The United States drops atomic bomb on Hiroshima (20 kiloton bomb 'Little Boy' kills 80,000) August 8: Russia declares war on Japan August 9: The United States drops atomic bomb on Nagasaki (22 kiloton 'Fat Man' kills 70,000) August 14 : Japanese surrender End of World War II August 15: Emperor surrender broadcast - VJ Day 1946 February 9: Stalin hostile speech - communism & capitalism were incompatible March 5 : "Sinews of Peace" Iron Curtain Speech by Winston Churchill - "an "iron curtain" has descended on Europe" March 10: Truman demands Russia leave Iran July 1: Operation Crossroads with Test Able was the first public demonstration of America's atomic arsenal July 25: America's Test Baker - underwater explosion 1947 Containment March 12 : Truman Doctrine - Truman declares active role in Greek Civil War June : Marshall Plan is announced setting a precedent for helping countries combat poverty, disease and malnutrition September 2: Rio Pact - U.S. meet 19 Latin American countries and created a security zone around the hemisphere 1948 Containment February 25 : Communist takeover in Czechoslovakia March 2: Truman's Loyalty Program created to catch Cold War -

Songs by Title

Karaoke Song Book Songs by Title Title Artist Title Artist #1 Nelly 18 And Life Skid Row #1 Crush Garbage 18 'til I Die Adams, Bryan #Dream Lennon, John 18 Yellow Roses Darin, Bobby (doo Wop) That Thing Parody 19 2000 Gorillaz (I Hate) Everything About You Three Days Grace 19 2000 Gorrilaz (I Would Do) Anything For Love Meatloaf 19 Somethin' Mark Wills (If You're Not In It For Love) I'm Outta Here Twain, Shania 19 Somethin' Wills, Mark (I'm Not Your) Steppin' Stone Monkees, The 19 SOMETHING WILLS,MARK (Now & Then) There's A Fool Such As I Presley, Elvis 192000 Gorillaz (Our Love) Don't Throw It All Away Andy Gibb 1969 Stegall, Keith (Sitting On The) Dock Of The Bay Redding, Otis 1979 Smashing Pumpkins (Theme From) The Monkees Monkees, The 1982 Randy Travis (you Drive Me) Crazy Britney Spears 1982 Travis, Randy (Your Love Has Lifted Me) Higher And Higher Coolidge, Rita 1985 BOWLING FOR SOUP 03 Bonnie & Clyde Jay Z & Beyonce 1985 Bowling For Soup 03 Bonnie & Clyde Jay Z & Beyonce Knowles 1985 BOWLING FOR SOUP '03 Bonnie & Clyde Jay Z & Beyonce Knowles 1985 Bowling For Soup 03 Bonnie And Clyde Jay Z & Beyonce 1999 Prince 1 2 3 Estefan, Gloria 1999 Prince & Revolution 1 Thing Amerie 1999 Wilkinsons, The 1, 2, 3, 4, Sumpin' New Coolio 19Th Nervous Breakdown Rolling Stones, The 1,2 STEP CIARA & M. ELLIOTT 2 Become 1 Jewel 10 Days Late Third Eye Blind 2 Become 1 Spice Girls 10 Min Sorry We've Stopped Taking Requests 2 Become 1 Spice Girls, The 10 Min The Karaoke Show Is Over 2 Become One SPICE GIRLS 10 Min Welcome To Karaoke Show 2 Faced Louise 10 Out Of 10 Louchie Lou 2 Find U Jewel 10 Rounds With Jose Cuervo Byrd, Tracy 2 For The Show Trooper 10 Seconds Down Sugar Ray 2 Legit 2 Quit Hammer, M.C.