The Bleedin' Irish Female Body

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Spring 2020, Volume 32, Number 1

THE CYPRUS REVIEW Spring 2020, Vol. 32, No. 1 THE CYPRUS REVIEW Spring 2020, Vol. Spring 2020, Volume 32, Number 1 Published by the University of Nicosia ISSN 1015-2881 (Print) | ISSN 2547-8974 (Online) P.O. Box 24005 1700 Nicosia, Cyprus T: 22-842301, 22-841500 E: [email protected] www.cyprusreview.org SUBSCRIPTION OFFICE: The Cyprus Review University of Nicosia 46 Makedonitissas Avenue 1700 Nicosia, Cyprus Copyright: © 2020 University of Nicosia, Cyprus ISSN 1015-2881 (Print), 2547-8974 (Online) DISCLAIMER The views expressed in the articles All rights reserved. and reviews published in this journal No restrictions on photo-copying. are those of the authors and do Quotations from The Cyprus Review not necessarily represent the views are welcome, but acknowledgement of the University of Nicosia, the Editorial Board, or the Editors. of the source must be given. EDITORIAL TEAM Editor-in-Chief: Dr Christina Ioannou Consulting Editor: Prof. Achilles C. Emilianides Managing Editor: Dr Emilios A. Solomou Publications Editor: Dimitrios A. Kourtis Assistant Editor: Dr Maria Hadjiathanasiou Copy Editor: Mary Kammitsi Publication Designer: Thomas Costi EDITORIAL BOARD Dr Constantinos Adamides University of Nicosia Prof. Panayiotis Angelides University of Nicosia Dr Odysseas Christou University of Nicosia Prof. Costas M. Constantinou University of Cyprus Prof. Dimitris Drikakis University of Nicosia Prof. Hubert Faustmann University of Nicosia EDITORIAL Dr Sofia Iordanidou Open University of Cyprus Prof. Andreas Kapardis University of Cyprus -

Rita Nowak Homo Kallipygos 03.10.19

Rita Nowak Homo Kallipygos 03.10.19 - 26.10.19 Mittwoch-Samstag, 12.00-18.00 Matthew Bown Gallery Pohlstrasse 48 10785 Berlin Rita Nowak's exhibition Homo Kallipygos is a series of photographs, of artists and not- artists, shot in Vienna, London and elsewhere. Fraternity, sorority; physical intimacy made compatible with the formality of spectacle; and the allure of the nude body are explored via the motif of the buttocks: the preferred, gender-neutral, erogenous zone of our age. The title of the show derives from the Aphrodite Kallipygos (aka Callipygian Venus), literally, Venus of the Beautiful Buttocks, a Roman copy in marble of an original Greek bronze [1]. Aphrodite's pose is an example of anasyrma: the act of lifting one's skirt to expose the nether parts for the pleasure of spectators [2]. Nowak's student diploma work, Ultravox (2004), referred to Henry Wallis's Death of Chatterton (1856), since when Nowak has regularly evoked the heritage of figurative painting. Centrefold cites an earlier pin-up, Boucher's Blonde Odalisque (1751-2), the image of a fourteen-year-old model, Marie-Louise O'Murphy [3]. Tobias Urban, a member of the Vienna-based artists' group Gelitin, sprawls not on a velvet divan in the boudoir but on that icon of contemporary consumerism, an abandoned faux-leather sofa, installed in a sea of mud. The title suggests that Urban, like O'Murphy, is intended as an object of our erotic fantasy; the pose is subtly altered from Boucher's original, the point- of-view is shifted a few degrees: we see a little less of the face, more of the buttocks and genitals [4]. -

The Potential of Leaks: Mediation, Materiality, and Incontinent Domains

THE POTENTIAL OF LEAKS: MEDIATION, MATERIALITY, AND INCONTINENT DOMAINS ALYSSE VERONA KUSHINSKI A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF GRADUATE STUDIES IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY GRADUATE PROGRAM IN COMMUNICATION AND CULTURE YORK UNIVERSITY TORONTO, ONTARIO AUGUST 2019 © Alysse Kushinski, 2019 ABSTRACT Leaks appear within and in between disciplines. While the vernacular implications of leaking tend to connote either the release of texts or, in a more literal sense, the escape of a fluid, the leak also embodies more poetic tendencies: rupture, release, and disclosure. Through the contours of mediation, materiality, and politics this dissertation traces the notion of “the leak” as both material and figurative actor. The leak is a difficult subject to account for—it eludes a specific discipline, its meaning is fluid, and its significance, always circumstantial, ranges from the entirely banal to matters of life and death. Considering the prevalence of leakiness in late modernity, I assert that the leak is a dynamic agent that allows us to trace the ways that actors are entangled. To these ends, I explore several instantiations of “leaking” in the realms of media, ecology, and politics to draw connections between seemingly disparate subjects. Despite leaks’ threatening consequences, they always mark a change, a transformation, a revelation. The leak becomes a means through which we can challenge ourselves to reconsider the (non)functionality of boundaries—an opening through which new possibilities occur, and imposed divisions are contested. However, the leak operates simultaneously as opportunity and threat—it is always a virtual agent, at once stagnant and free flowing. -

Menstruation Regulation: a Feminist Critique of Menstrual Product Brands on Instagram

East Tennessee State University Digital Commons @ East Tennessee State University Undergraduate Honors Theses Student Works 5-2020 Menstruation Regulation: A Feminist Critique of Menstrual Product Brands on Instagram Max Faust Follow this and additional works at: https://dc.etsu.edu/honors Part of the Critical and Cultural Studies Commons, Gender and Sexuality Commons, Gender, Race, Sexuality, and Ethnicity in Communication Commons, Health Communication Commons, Mass Communication Commons, Social Media Commons, Speech and Rhetorical Studies Commons, Women's History Commons, and the Women's Studies Commons Recommended Citation Faust, Max, "Menstruation Regulation: A Feminist Critique of Menstrual Product Brands on Instagram" (2020). Undergraduate Honors Theses. Paper 576. https://dc.etsu.edu/honors/576 This Honors Thesis - Open Access is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Works at Digital Commons @ East Tennessee State University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Undergraduate Honors Theses by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ East Tennessee State University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Running Head: FEMINIST CRITIQUE OF INSTAGRAM PERIOD PRODUCT BRANDS 1 Menstruation Regulation: A Feminist Critique of Menstrual Product Brands on Instagram By Max Faust An Undergraduate Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the University Honors Scholars Program Honors College College of Arts and Sciences East Tennessee State University ___________________________________________ Max Faust Date ___________________________________________ Dr. C. Wesley Buerkle, Thesis Mentor Date ___________________________________________ Dr. Kelly A. Dorgan, Reader Date FEMINIST CRITIQUE OF INSTAGRAM PERIOD PRODUCT BRANDS 2 Abstract Much research about advertisements for menstrual products reveals the ways in which such advertising perpetuates shame and reinforces unrealistic ideals of femininity and womanhood. -

Heb 2016 31 1 30-46

Human Ethology Bulletin – Proc. of the V. ISHE Summer Institute (2016): 30-46 Theoretical Review UNIVERSALS IN RITUALIZED GENITAL DISPLAY OF APOTROPAIC FEMALE FIGURES Christa Sütterlin Human Ethology Group, Max-Planck Institute for Ornithology, Seewiesen, Germany. [email protected] ABSTRACT Human genital display as part of the sculptural repertoire was presented and discussed within a wider ethological framework in the sixties of the last century. Male phallic display is widely referred to as a rank demonstration and ritualized threat rooted in male sexual behavior, and it is discussed as a symbolic dominance display and defense in the artistic context as well. Female sexual display in sculptures, however, is prevalently interpreted in terms of erotic and fertility aspects in art literature. Ethologically it is described as a gesture with at least ambivalent meaning. A recent analysis of its artistic presentation in the nineties of the last century has given rise to a new discussion of its function and meaning, on the behavioral as well as on the sculptural level. Cross- cultural consistency, functional context and expressive cues thereby play a primary role in this regard. In addition, a new consideration of behavioral relicts contributes to reinterpreting the gesture, both ethologically and artistically. The concept of ritualization may be of particular help for a better understanding of its archaic behavioral background and its special relevance for the arts. The sculptural motive is in the meantime partially accepted as an “apotropaic” (aversive) motive even in archaeological circles, but any derivation from behavioral origins is still far away from being integrated. Keywords: Female genital display, ethology, ritualization, art, and cultural comparison. -

Body Politics and Menstrual Cultures in Contemporary Spain

Body Politics and Menstrual Cultures in Contemporary Spain A Research Paper presented by: Claudia Lucía Arbeláez Orjuela (Colombia) in partial fulfilment of the requirements for obtaining the degree of MASTER OF ARTS IN DEVELOPMENT STUDIES Major: Social Policy for Development SPD Members of the Examining Committee: Wendy Harcourt Rosalba Icaza The Hague, The Netherlands November 2017 ii A mis padres iii Contents List of Appendices vii Chapter 1 Introduction 1 1.1. Research question 4 1.2. Structure 4 Chapter 2 Some Voices to rely on 5 2.1. Entry point: Menstrual Activism 6 2.2. Corporeal feminism 7 2.3. Body Politics 8 Chapter 3 The Setting 10 3. 1. Exploring the menstrual cultures in Contemporary Spain 10 3.2. Activist and feminist Barcelona 11 Chapter 4 Methodology 14 4.1. Embodied Knowledges: A critical position from feminist epistemology 14 4.2. Semi-structured Interviews 15 4.3. Ethnography and Participant observation 16 4.4. Netnography 16 Chapter 5 Let it Bleed: Art, Policy and Campaigns 17 5.1. Menstruation and Art 17 5.1.1 Radical Menstruators 17 5.1.2. Lola Vendetta and Zinteta: glittery menstruation and feminism(s) for millenials. 20 5.2. ‘Les Nostres Regles’ 23 5.3. Policy 25 5.3.1. EndoCataluña 25 iv 5.3.2. La CUP’s Motion 26 Chapter 6 Menstrual Education: lessons from the embodied experience 29 6.1. Divine Menstruation – A Natural Gynaecology Workshop 31 6.2. Somiarte 32 6.3. Erika Irusta and SOY1SOY4 34 Chapter 7 Sustainable menstruation: ecological awareness and responsible consumption 38 7.1. -

The+Dawkins-Kardashian+Steal.Pdf (9.472Mb)

A PASTICHE on DOCUMENTATION of ARTISTIC RESEARCH by BJØRN JØRUND BLIKSTAD The Dawkins-Kardashian Stela Documentation of artistic research / KUF in the form of bas relief by Bjørn Jørund Blikstad, as part of a phd project, Level Up, on design from Oslo National Academy of the Arts 2019. Materials: Sipo/utile head and base Birch body Ultramarine surface, linseed oil paint Turned and chrome painted wooden ufo insert Eckart Bleichgold Made in 2019 from March to October by BJB at locations: Oslo National Academy of the Arts Tune Handel, Tørberget Ormelett, Tjøme Studio photography of stela 17.10.2019 by BJB & Olympus self timer Other images: Page 10: Furrysaken, Universitas 17.10.2018 (Henrik Follesø Egeland) Page 11: T-Shaped pilars from the excavation site at Göebekli Tepe, Turkey 2011. (Creative Commons) Page 12: Retouched kartouche, Karnak, Luxor 2011 (BJB) Page 13: Herma of Dionysos. Attributed to the Workshop of Boëthos of Kalchedon. Greek, active about 200 - 100 B.C. (J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles) Page 14: Neues Reich. Dynastie XVIII. Pyramiden von Giseh. Stele vor dem grossen Sphinx. Litography by Ernst WeidenBach. (C C) Page 15: Illustration by Charles Eisen for The Devil of Pope-Fig Island by Jean de la Fontaine: Tales and Novels in Verse. London 1896. (C C) Standard fonts & formats ISBN: 978-82-7038-400-6 TO THE READER Don’t read the introduction to ufology first. Jump straight to the explanations of the have used to conceptualize alterity and change” (Astruc, 2010). By doing that, we constituent elements of the Stela (page 32) before continuing to the introduction, discover a predicament. -

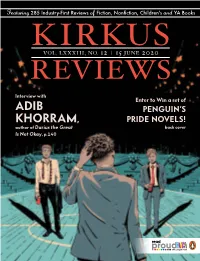

Kirkus Reviews

Featuring 285 Industry-First Reviews of Fiction, Nonfiction, Children'sand YA Books KIRKUSVOL. LXXXIII, NO. 12 | 15 JUNE 2020 REVIEWS Interview with Enter to Win a set of ADIB PENGUIN’S KHORRAM, PRIDE NOVELS! author of Darius the Great back cover Is Not Okay, p.140 with penguin critically acclaimed lgbtq+ reads! 9780142425763; $10.99 9780142422939; $10.99 9780803741072; $17.99 “An empowering, timely “A narrative H“An empowering, timely story with the power to experience readers won’t story with the power to help readers.” soon forget.” help readers.” —Kirkus Reviews —Kirkus Reviews —Kirkus Reviews, starred review A RAINBOW LIST SELECTION WINNER OF THE STONEWALL A RAINBOW LIST SELECTION BOOK AWARD WINNER OF THE PRINTZ MEDAL WINNER OF THE PRINTZ MEDAL 9780147511478; $9.99 9780425287200; $22.99 9780525517511; $8.99 H“Enlightening, inspiring, “Read to remember, “A realistic tale of coming and moving.” remember to fight, fight to terms and coming- —Kirkus Reviews, starred review together.” of-age… with a touch of —Kirkus Reviews magic and humor” A RAINBOW LIST SELECTION —Kirkus Reviews Featuring 285 Industry-First Reviews of Fiction, Nonfiction, Children’s,and YA Books. KIRKUSVOL. LXXXVIII, NO. 12 | 15 JUNE 2020 REVIEWS THE PRIDEISSUE Books that explore the LGBTQ+ experience Interviews with Meryl Wilsner, Meredith Talusan, Lexie Bean, MariNaomi, L.C. Rosen, and more from the editor’s desk: Our Books, Ourselves Chairman HERBERT SIMON BY TOM BEER President & Publisher MARC WINKELMAN John Paraskevas # As a teenager, I stumbled across a paperback copy of A Boy’s Own Story Chief Executive Officer on a bookstore shelf. Edmund White’s 1982 novel, based loosely on his MEG LABORDE KUEHN [email protected] coming-of-age, was already on its way to becoming a gay classic—but I Editor-in-Chief didn’t know it at the time. -

Cretan Sanctuaries and Cults Religions in the Graeco-Roman World

Cretan Sanctuaries and Cults Religions in the Graeco-Roman World Editors H.S. Versnel D. Frankfurter J. Hahn VOLUME 154 Cretan Sanctuaries and Cults Continuity and Change from Late Minoan IIIC to the Archaic Period by Mieke Prent BRILL LEIDEN • BOSTON 2005 This series Religions in the Graeco-Roman World presents a forum for studies in the social and cul- tural function of religions in the Greek and the Roman world, dealing with pagan religions both in their own right and in their interaction with and influence on Christianity and Judaism during a lengthy period of fundamental change. Special attention will be given to the religious history of regions and cities which illustrate the practical workings of these processes. Enquiries regarding the submission of works for publication in the series may be directed to Professor H.S. Versnel, Herenweg 88, 2361 EV Warmond, The Netherlands, [email protected]. This book is printed on acid-free paper. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Prent, Mieke. Cretan sanctuaries and cults : continuity and change from Late Minoan IIIC to the Archaic period / by Mieke Prent. p. cm. — (Religions in the Graeco-Roman world, ISSN 0927-7633 ; v. 154) Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 90-04-14236-3 (alk. paper) 1. Crete (Greece)—Religion. 2. Shrines—Greece—Crete. 3. Crete (Greece)— Antiquities. I. Title. II. Series. BL793.C7P74 2005 292.3'5'09318—dc22 2004062546 ISSN 0927–7633 ISBN 90 04 14236 3 © Copyright 2005 by Koninklijke Brill NV, Leiden, The Netherlands Koninklijke Brill NV incorporates the imprints Brill Academic Publishers, Martinus Nijhoff Publishers and VSP. -

Sacred Display: New Findings

SINO-PLATONIC PAPERS Number 240 September, 2013 Sacred Display: New Findings by Miriam Robbins Dexter and Victor H. Mair Victor H. Mair, Editor Sino-Platonic Papers Department of East Asian Languages and Civilizations University of Pennsylvania Philadelphia, PA 19104-6305 USA [email protected] www.sino-platonic.org SINO-PLATONIC PAPERS FOUNDED 1986 Editor-in-Chief VICTOR H. MAIR Associate Editors PAULA ROBERTS MARK SWOFFORD ISSN 2157-9679 (print) 2157-9687 (online) SINO-PLATONIC PAPERS is an occasional series dedicated to making available to specialists and the interested public the results of research that, because of its unconventional or controversial nature, might otherwise go unpublished. The editor-in-chief actively encourages younger, not yet well established, scholars and independent authors to submit manuscripts for consideration. Contributions in any of the major scholarly languages of the world, including romanized modern standard Mandarin (MSM) and Japanese, are acceptable. In special circumstances, papers written in one of the Sinitic topolects (fangyan) may be considered for publication. Although the chief focus of Sino-Platonic Papers is on the intercultural relations of China with other peoples, challenging and creative studies on a wide variety of philological subjects will be entertained. This series is not the place for safe, sober, and stodgy presentations. Sino- Platonic Papers prefers lively work that, while taking reasonable risks to advance the field, capitalizes on brilliant new insights into the development of civilization. Submissions are regularly sent out to be refereed, and extensive editorial suggestions for revision may be offered. Sino-Platonic Papers emphasizes substance over form. We do, however, strongly recommend that prospective authors consult our style guidelines at www.sino-platonic.org/stylesheet.doc. -

Copyright by Jacqueline Kay Thomas 2007

Copyright by Jacqueline Kay Thomas 2007 The Dissertation Committee for Jacqueline Kay Thomas certifies that this is the approved version of the following dissertation: APHRODITE UNSHAMED: JAMES JOYCE’S ROMANTIC AESTHETICS OF FEMININE FLOW Committee: Charles Rossman, Co-Supervisor Lisa L. Moore, Co-Supervisor Samuel E. Baker Linda Ferreira-Buckley Brett Robbins APHRODITE UNSHAMED: JAMES JOYCE’S ROMANTIC AESTHETICS OF FEMININE FLOW by Jacqueline Kay Thomas, M.A. Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of The University of Texas at Austin in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy The University of Texas at Austin May, 2007 To my mother, Jaynee Bebout Thomas, and my father, Leonard Earl Thomas in appreciation of their love and support. Also to my brother, James Thomas, his wife, Jennifer Herriott, and my nieces, Luisa Rodriguez and Madeline Thomas for providing perspective and lots of fun. And to Chukie, who watched me write the whole thing. I, the woman who circles the land—tell me where is my house, Tell me where is the city in which I may live, Tell me where is the house in which I may rest at ease. —Author Unknown, Lament of Inanna on Tablet BM 96679 Acknowledgements I first want to acknowledge Charles Rossman for all of his support and guidance, and for all of his patient listening to ideas that were creative and incoherent for quite a while before they were focused and well-researched. Chuck I thank you for opening the doors of academia to me. You have been my champion all these years and you have provided a standard of elegant thinking and precise writing that I will always strive to match. -

Menstrual Justice

Menstrual Justice Margaret E. Johnson* Menstrual injustice is the oppression of menstruators, women, girls, transgender men and boys, and nonbinary persons, simply because they * Copyright © 2019 Margaret E. Johnson. Professor of Law, Co-Director, Center on Applied Feminism, Director, Bronfein Family Law Clinic, University of Baltimore School of Law. My clinic students and I have worked with the Reproductive Justice Coalition on legislative advocacy for reproductive health care policies and free access to menstrual products for incarcerated persons since fall 2016. In 2018, two bills became law in Maryland requiring reproductive health care policies in the correctional facilities as well as free access to products. Maryland HB 787/SB629 (reproductive health care policies) and HB 797/SB 598 (menstrual products). I want to thank the Coalition members and my students who worked so hard on these important laws and are currently working on their implementation and continued reforms. I also want to thank the following persons who reviewed and provided important feedback on drafts and presentations of this Article: Professors Michele Gilman, Shanta Trivedi, Virginia Rowthorn, Nadia Sam-Agudu, MD, Audrey McFarlane, Lauren Bartlett, Carolyn Grose, Claire Donohue, Phyllis Goldfarb, Tanya Cooper, Sherley Cruz, Naomi Mann, Dr. Nadia Sam-Agudu, Marcia Zug, Courtney Cross, and Sabrina Balgamwalla. I want to thank Amy Fettig for alerting me to the breadth of this issue. I also want to thank Bridget Crawford, Marcy Karin, Laura Strausfeld, and Emily Gold Waldman for collaborating and thinking about issues relating to periods and menstruation. And I am indebted to Max Johnson-Fraidin for his insight into the various critical legal theories discussed in this Article and Maya Johnson-Fraidin for her work on menstrual justice legislative advocacy.