Hellendaal “Cambridge” Sonatas

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Johannes Berghuys and His Son Frederik Berghuys

Johannes Berghuys and his son Frederik Berghuys two Delft carillonneurs from 1741 to 1835 and their collection of music for carillon Dr. Laura J. Meilink-Hoedemaker Rotterdam, the Netherlands This article is based upon two papers presented at the Meeting of the World Carillon Federation, Ann Arbor, Michigan, and the Annual Meeting of the Guild of Carillonneurs in North America, Ottawa, Canada July 1986 Pagina 1 van 7 www.laurameilink.nl Mr Chairman, Ladies and Gentlemen This paper presents some data on the life and the works of Johannes Berghuys and his son Frederik Berghuys, city carillonneurs in Delft, the Netherlands, at the end of the 18th and the beginning of the 19th century. The city of Delft is situated in the old district of Holland. From early days Delft had connections with other Dutch cities such as The Hague, Haarlem, Leiden, Gouda, Rotterdam and Amsterdam. Johannes Berghuys was the second child born to taylor Frederik Berghuys and Alida Meyers who lived in Zutphen, but originally came from The Hague. The first son, Johannes, died shortly after birth in 1721. A second son, also called Johannes, was born in 1724. At the age of 17 this Johannes Berghuys moved to Delft upon being appointed city carillonneur. His parents settled with him there. At the age of 32 Johannes Berghuys married Maria Otte from The Hague. That same year their daughter Alida was born and six years later they had their son Frederik. No details are known about the family life and professional training of Johannes Berghuys in his Zutphen periode. -

Wie Kent Pieter Hellendaal Nog? Antoinette Lohmann Haalt De Componist Terug Met Een Set Stikmoeilijke Vioolsonates

Wie kent Pieter Hellendaal nog? Antoinette Lohmann haalt de componist terug met een set stikmoeilijke vioolsonates Rotterdam naar Utrecht. vioolspelen zelf. Maar vaker zat het tegen, 'Hij moet een ongelooflijke techniek professioneel en persoonlijk nog hebben gehad, hij schreef de meer. Zo werd zijn vader Johan op sonates in de eerste plaats om brute wijze vermoord, nadat hij had zichzelf als violist te presenteren. geprobeerd te bemiddelen bij een Hij heeft dingen genoteerd die je echtscheiding. Een Zweedse niet meteen begrijpt als je ze voor huurmoordenaar probeerde papa het eerst ziet. Hij vraagt Hellendaal eerst te vergiftigen. bijvoorbeeld om heel Toen dat mislukte, bewerkte hij de ongebruikelijke dubbelgrepen. Ik man met een bijl. Zijn ledematen stel me dan voor dat hij, wanneer werden verspreid over diverse hij zo'n passage speelde, grijnzend Amsterdamse grachten en tuinen. vanuit een ooghoek zijn vriendjes in de kroeg opzocht. Zo van: zag je Het verhaal is te lezen in het boekje wat ik deed?' Violist Antoinette Lohmann: 'Ik speel bij het nieuwe album van Antoinette graag onontgonnen repertoire omdat ik Lohmann, de barokviolist die er een Dat technisch meesterschap deed dan niet beïnvloed ben door andere sport van maakt goed maar Hellendaal op in Padua. Daar visies.' vergeten Nederlands repertoire studeerde hij viool en compositie bij Daniel Cohen onder de aandacht te brengen. 'Ik de beroemde vioolpedagoog ben altijd benieuwd naar wat er in Giuseppe Tartini (1692-1770). mijn eigen land gebeurd is', zegt Nederland profiteerde nauwelijks Lohmann. 'Maar onontgonnen van zijn talent - of zag het niet. Hij repertoire speel ik vooral graag woonde nog in Amsterdam en omdat ik dan niet beïnvloed ben Leiden, maar slaagde er niet in om door andere visies. -

20 March 2021

20 March 2021 12:01 AM Benjamin Ipavec (1839-1908) Lahko Noc Ana Pusar-Jeric (soprano), Natasa Valant (piano) SIRTVS 12:05 AM Claude Debussy (1862-1918), Luc Brewaeys (arranger) La cathedrale engloutie - (No 10 from Preludes - Book 1) Royal Flemish Philharmonic, Daniele Callegari (conductor) BERTBF 12:12 AM Darius Milhaud (1892-1974) 3 Psaumes de David for chorus, Op 339 Elmer Iseler Singers, Elmer Iseler (conductor) CACBC 12:21 AM Pieter Hellendaal (1721-1799) Cello Sonata, Op 5 no 7 (1780) Jaap ter Linden (cello), Ton Koopman (harpsichord), Ageet Zweistra (cello) NLNOS 12:32 AM Joseph Haydn (1732-1809) String Quartet in D major (Op.64, No.5) (Hob.III.63) "Lark" Bartok String Quartet HUMR 12:50 AM Frederick Delius (1862-1934) In a Summer Garden for orchestra BBC Symphony Orchestra, Andrew Davis (conductor) GBBBC 01:07 AM Ignacy Jan Paderewski (1860-1941) Polish Fantasy, Op 19 Lukasz Krupinski (piano), Santander Orchestra, Lawrence Foster (conductor) PLPR 01:29 AM Gustav Mahler (1860-1911) Ich ging mit lust durch einen grunen Wald Arleen Auger (soprano), Irwin Gage (piano) NLNOS 01:34 AM Johan Peter Emilius Hartmann (1805-1900) 6 Characteerstykker med indledende Smaavers af H.C Andersen, Op 50 Nina Gade (piano) DKDR 01:46 AM Giovanni Battista Pergolesi (1710-1736) Violin Concerto in B flat major Andrea Keller (violin), Concerto Koln DEWDR 02:01 AM Sergey Rachmaninov (1873-1943) Trio élégiaque no 1 in G minor Sascha Maisky (violin), Mischa Maisky (cello), Lily Maisky (piano) BERTBF 02:15 AM Dmitry Shostakovich (1906-1975) Piano Trio no -

St John's Smith Square

ST JOHN’S SMITH SQUARE 2015/16 SEASON Discover a musical landmark Patron HRH The Duchess of Cornwall 2015/16 SEASON CONTENTS WELCOME TO ST JOHN’S SMITH SQUARE —— —— 01 Welcome 102 School concerts Whether you’re already a friend, or As renovation begins at Southbank 02 Season Overview 105 Discover more discovering us for the first time, I trust Centre, we welcome residencies from the 02 Orchestral Performance 106 St John’s history you’ll enjoy a rewarding and stimulating Orchestra of the Age of Enlightenment 03 Choral & Vocal Music 108 Join us experience combining inspirational and London Sinfonietta, world-class 03 Opera 109 Subscription packages music, delicious food and good company performers from their International Piano 04 Period Instruments 110 Booking information in the fabulous grandeur of this historic Series and International Chamber Music 05 Regular Series 111 How to find us building – the UK’s only baroque Series, and a mid-summer performance 06 New Music 112 Footstool Restaurant concert venue. from the Philharmonia Orchestra. 07 Young Artists’ Scheme This is our first annual season brochure We’re proud of our reputation for quality 08 Festivals – a season that features more than 250 and friendly service, and welcome the 09 Southbank Centre concerts, numerous world premieres and thoughts of our visitors. So, if you have 10 Listings countless talented musicians. We’re also any comments, please let me know and discussing further exciting projects, so I’ll gladly discuss them with you. please keep an eye on our What’s On I look forward to welcoming you to guides or sign up to our e-newsletter. -

15 May 2020 Page 1 of 12

Radio 3 Listings for 9 – 15 May 2020 Page 1 of 12 SATURDAY 09 MAY 2020 04:25 AM https://www.deutschegrammophon.com/en/catalogue/products/ Pieter Hellendaal (1721-1799) vinci-veni-vidi-vinci-fagioli-11926 SAT 01:00 Through the Night (m000hx7r) Sonata Prima in G major (Op.5) RIAS Chamber Chorus with Capella de la Torre Jaap ter Linden (cello), Ton Koopman (harpsichord), Ageet Vaughan Williams: Horn Sonata, Quintet, Household Music & Zweistra (cello) Bax: Horn Sonata James MacMilan, Gabrieli, Schutz and Praetorius from the Peter Francomb (horn) 2019 Heinrich Schütz Music Festival. Jonathan Swain presents. 04:34 AM Victor Sangiorgio (piano) Alexander Glazunov (1865-1936) Royal Northern Sinfonia Chamber Ensemble 01:01 AM Concert waltz for orchestra no 2 in F major, Op 51 Dutton Epoch CDLX 7373 (Hybrid SACD) James MacMillan (b.1959) CBC Vancouver Symphony Orchestra, Kazuyoshi Akiyama https://www.duttonvocalion.co.uk/proddetail.php?prod=CDLX Miserere (conductor) 7373 Stephanie Petitlaurent (soprano), Waltraud Heinrich (alto), Jorg Genslein (tenor), Andrew Redmond (bass), Goethe Secondary 04:42 AM Kreek: the Suspended Harp of Babel School Chorus, Gera Franz Schubert (1797-1828) Choral music of Cyrillus Kreek Trio in B flat D.471 Vox Clamantis 01:14 AM Trio AnPaPie ECM 4819041 Heinrich Schutz (1585-1672) https://www.ecmrecords.com/catalogue/1575278895 Magnificat a 14, from 'Sacrae symphoniae II' 04:51 AM RIAS Chamber Chorus, Berlin, Justin Doyle (director), Capella Antonio Vivaldi (1678-1741) Grigory Sokolov - Beethoven, Brahms & Mozart de la -

Violin Concertos from Darmstadt

Kress Violin Concertos from Darmstadt Violin concertos from the Darmstadt court Georg Philipp Telemann (1681–1767) Concerto in D Major, TWV 53:D5 for trumpet, violino concertato, violoncello obbligato, strings and basso continuo 01 Vivace 3 : 35 02 Adagio 4 : 00 03 Allegro 4 : 59 12 : 34 Johann Jakob Kress (c1685 –1728) Concerto à 5 in C Minor, Op. 1, No. 2* for violino principale, strings and basso continuo 04 Allegro 2 : 53 05 Adagio 2 : 05 06 Allegro 2 : 52 7: 50 Johann Friedrich Fasch (1688 – 1758) Concerto in D Major, FWV L:D4a* for solo violin, 3 trumpets, timpani, oboes, bassoon, strings and basso continuo 07 Allegro 5 : 20 08 Andante 2 : 16 09 Allegro 5 : 40 13 : 13 4 Johann Jakob Kress Concerto à 5 in C Major, Op. 1, No. 6 * for violino principale, strings and basso continuo 10 Adagio 3 : 18 11 Allegro 2 : 50 12 Adagio 2 : 14 13 Allegro 2 : 08 10 : 30 Johann Samuel Endler (1694 —1762) Ouverture (Orchestral suite) in D Major* for violin, 3 trumpets, timpani, oboes, bassoon, strings and basso continuo 14 Ouverture 7 : 10 15 Vivement 2 : 25 16 La Brouillerie 1 : 52 17 Menuett 2 : 31 18 Réjouissance 3 : 09 19 Fantasie 1: 32 20 Passepied 3 : 05 21 Le Causeur 2 : 04 23:48 * World premiere recording 5 Johannes Pramsohler solo violin & director / Solovioline & Leitung / violon solo & direction Violin Giovanni Battista Guadagnini, Piacenza 1745 Manfred Bockschweiger solo trumpet / Solotrompete / trompette solo 6 Darmstädter Barocksolisten Members and guests of the Staatsorchester Darmstadt (on modern instruments) Ethem Emre Tamer, Christian -

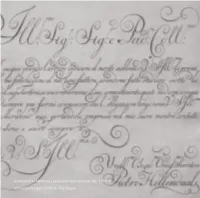

Dedication to Mattheus Lestevenon from Sonatas Op. 1 (1744) Netherlands Music Institute, the Hague

Dedication to Mattheus Lestevenon from Sonatas Op. 1 (1744) Netherlands Music Institute, The Hague Furor Musicus at the Lutherse Kerk, Hilversum (© Christiaan de Roo) 2 3 PIETER (PETRUS, PIETRO, PETER) HELLENDAAL ROTTERDAM 1721 - CAMBRIDGE 1799 Pieter Hellendaal was born in Rotterdam in 1721. While little is known about his family’s circumstances and background, tax records indicate that the family was not particularly well off. His father, Johan Hellendaal, was registered as being a pastry baker, but he changed his profession to candlemaker when the family moved to Utrecht in 1731, where it was registered under the name of Hellendael. UTRECHT, 1731 -1737 In 1732, at the tender age of ten, Pieter was appointed as organist of the Nicolaïkerk in Utrecht, on condition that his father Johan would assist him. While this suggests that his father was also a musician and may even have been Pieter’s teacher, there is no actual historical evidence to support this surmise. The churchwardens’ resolu- tions include instructions dating from 1732, presumably specially drafted for young Pieter. Besides giving a precise description of the organist’s duties, they also include instructions for the use of the church’s Gerritsz organ. For instance, the smaller the congregation, the fewer stops he was required to use. Despite his youth, Pieter earned the same salary as his predecessor. Nicolaïkerk in Utrecht (drawing Pierre van Liender, 1756) Het Utrechts Archief collection, catalogue number 37465 4 5 His father Johan Hellendaal apparently knew a lot about organs, as he carried is evident from the first edition of the sonatas for violin and continuo opus 1 and out some repair work to the organ in 1732. -

12 April 2019 Page 1 of 12

Radio 3 Listings for 6 – 12 April 2019 Page 1 of 12 SATURDAY 06 APRIL 2019 5:30 am Mahler wrote his 4th Symphony on the very cusp of the Ludwig van Beethoven (1770-1827) Twentieth Century and it was premiered in Munich on 25th SAT 00:30 Music Planet World Mix (m0003tnj) 8 Variations on Mozart's 'La ci darem la mano' November 1901. Since Mahler's death, his 4th Symphony has Songs for girls, gringos and gangsters Hyong-Sup Kim (male) (oboe), Ja-Eun Ku (male) (piano) come to be recognised as one of his most 'classical' and approachable of his symphonic works, although it was Global beats and roots music from every corner of the world - 5:39 am considered to be a sacrilegious modernist work at the time of its with vintage mento from Jamaica, songs of the Sicilian Mafia, Lars-Erik Larsson (1908-1986) premiere. It completes the tetralogy of his first four and a version of Mexico's most famous song. String Quartet No.3 (Op.65) (1975) symphonies, his 'Wunderhorn' symphonies, so called because Uppsala Kammar Solister, Peter Olofsson (violin), Patrik they each reversion music from his orchestral Wunderhorn Swedrup (violin), Åsa Karlsson (viola), Lars Frykholm (cello) songs. In the case of the Fourth Symphony, it is the disquieting SAT 01:00 Through the Night (m0003tnl) song 'Das himmlische leben' that permeates the entire work and Chamber Music from Madrid 5:50 am then comes to the fore when solo soprano joins forces with the Claude Debussy (1862-1918) orchestra for the final movement. -

Musicians of Ma'alwyck Presents

Musicians of Ma’alwyck Presents Celebrating Dutch Heritage in New York’s Capital Region Through History and Music Part 2: Schuyler Mansion Program Ann-Marie Barker Schwartz, Director & Violin Norman Thibodeau, Flute André Laurent O’Neil, Baroque Cello Alfred V. Fedak, Harpsichord Andrew Snow, Viola Timothy Reno, Tenor The concert is supported as part of the Dutch Culture USA program by the Consulate General of the Netherlands in New York. Flute Quartet in D Minor, op 12/3 Christian Ernst Graf Allegro moderato (1723-1804) Largo Presto Sonata Op 4/3 Johannes Kauchlitz Colizzi Largo-Allegro (1742-1808) Minuetto I-II-III Variations on a Favorite Air from ”The Haunted Tower” Johannes Kauchlitz Colizzi Andante with Variations for Viola with Violin Accompaniment Josephus Andreas Fodor (1751-1828) Strephon and Myrtilla, a Cantata Pieter Hellendaal (1721-1799) Our thanks to Dr. Paula Quint at the Netherlands Music Institute in The Hauge, Netherlands for her assistance in procuring the score to the Hellendaal. Additional funding is provided by Stewart's Shops and The Dake Family, a fund of The Community Foundation for the Greater Capital Region The JM McDonald Foundation Program Notes The shadows cast by the legacies of Mozart, Haydn, and 18th century Italian opera composers tend to obscure, from a historical perspective, the quality and prominence of other composers of the same era. Each country had a stable of composers that were well-respected, popular and influential. Examining concert programs from England and America of the 1780s and 90s you can find music of these now nearly forgotten composers: Gretry, Pleyel, Martini, Shield, Vanhal, Gyrowitz and Dittersdorf to cite just a few. -

Radio 3 Listings for 25 April – 1 May 2020 Page

Radio 3 Listings for 25 April – 1 May 2020 Page 1 of 12 SATURDAY 25 APRIL 2020 Trumpet Concerto in D major Marc'Antonio Ingegneri: Missa Laudate Pueri Dominum and Stanko Arnold (trumpet), Slovenian Soloists, Marko Munih Giovanni Croce: In spiritu humilitatis SAT 01:00 Through the Night (m000hhpw) (conductor) Choir of Girton College Beethoven symphonies 3 and 5 Wayne Weaver (organ) 05:41 AM James Mitchell (organ) Le Concert des Nations with Jordi Savall, in Barcelona. Franz Liszt (1811-1886) Historic Brass of the Guildhall School and Royal Welsh College Catriona Young presents. Apres une Lecture de Dante: Fantasia quasi Sonata of Music and Drama Yuri Boukoff (piano) Gareth Wilson (conductor) 01:01 AM Toccata Classics TOCC0556 Ludwig van Beethoven (1770-1827) 05:57 AM https://toccataclassics.com/product/marcantonio-ingegneri- Symphony No 3 in E flat, op 55 'Eroica' Johann Baptist Vanhal (1739-1813) missa-laudate-pueri-dominum/ Le Concert des Nations, Jordi Savall (conductor) Concerto for 2 bassoons and orchestra Kim Walker (bassoon), Sarah Warner Vik (bassoon), John Adams: Must the Devil Have All the Good Tunes? and 01:46 AM Trondheim Symphony Orchestra, Arvid Engegard (conductor) China Gates Ludwig van Beethoven (1770-1827) Yuja Wang (piano) Symphony No 5 in C minor, op 67 06:20 AM Los Angeles Philharmonic Orchestra Le Concert des Nations, Jordi Savall (conductor) Grzegorz Fitelberg (1879-1953) Gustavo Dudamel (conductor) Piesn o sokele (The Song about a Falcon) - symphonic Poem Deutsche Grammophon 4838289 (download) 02:20 AM (Op.18) https://www.deutschegrammophon.com/en/catalogue/products/a -

J.S. Bach the Art of Fugue

CHANNEL CLASSICS CCS SA 38316 J.S. Bach The Art of Fugue Rachel Podger Brecon Baroque Johannes Pramsohler Jane Rogers Alison McGillivray Marcin Świątkiewicz 1 Rachel Podger Rachel Podger, violin and director and Brecon Baroque “There is probably no more inspirational musician working today than Podger” The dynamic ensemble Brecon Baroque (Gramophone). Over the last two decades consists of an international line-up of some Rachel Podger has established herself as of the leading lights in the period-instrument a leading interpreter of the Baroque and world, including cellist Alison McGillivray, Classical music periods and has recently violist Jane Rogers, harpsichordist Marcin been described as “the queen of the Świątkiewicz and violinist Johannes baroque violin” (Sunday Times). She holds Pramsohler. The ensemble specialises in numerous award-winning recordings to mainly one-to-a-part performances but also her name ranging from early seventeenth- appears as a small baroque orchestra for century music to Mozart and Haydn. She Vivaldi, Telemann, Purcell and Handel. was educated in Germany and in England Rachel and Brecon Baroque’s debut CD, at the Guildhall School of Music and Drama, Bach Violin Concertos, attracted universal where she studied with David Takeno and critical acclaim and was quickly hailed as Micaela Comberti. a benchmark recording of these works. Rachel has enjoyed countless colla- Bach Double and Triple Concertos, was borations as a director and soloist with released to rave reviews in 2013 including musicians all over the world. Highlights CD of the week nominations for Classic include Jordi Savall, Masaaki Suzuki, The FM, BBC Radio 3 CD Review, HR2 Kultur Academy of Ancient Music, Holland Baroque (Germany) and WQXR (New York). -

Compact Discs / DVD-Blu-Ray Recent Releases - Spring 2017

Compact Discs / DVD-Blu-ray Recent Releases - Spring 2017 Compact Discs 2L Records Under The Wing of The Rock. 4 sound discs $24.98 2L Records ©2016 2L 119 SACD 7041888520924 Music by Sally Beamish, Benjamin Britten, Henning Kraggerud, Arne Nordheim, and Olav Anton Thommessen. With Soon-Mi Chung, Henning Kraggerud, and Oslo Camerata. Hybrid SACD. http://www.tfront.com/p-399168-under-the-wing-of-the-rock.aspx 4tay Records Hoover, Katherine, Requiem For The Innocent. 1 sound disc $17.98 4tay Records ©2016 4TAY 4048 681585404829 Katherine Hoover: The Last Invocation -- Echo -- Prayer In Time of War -- Peace Is The Way -- Paul Davies: Ave Maria -- David Lipten: A Widow’s Song -- How To -- Katherine Hoover: Requiem For The Innocent. Performed by the New York Virtuoso Singers. http://www.tfront.com/p-415481-requiem-for-the-innocent.aspx Rozow, Shie, Musical Fantasy. 1 sound disc $17.98 4tay Records ©2016 4TAY 4047 2 681585404720 Contents: Fantasia Appassionata -- Expedition -- Fantasy in Flight -- Destination Unknown -- Journey -- Uncharted Territory -- Esme’s Moon -- Old Friends -- Ananke. With Robert Thies, piano; The Lyris Quartet; Luke Maurer, viola; Brian O’Connor, French horn. http://www.tfront.com/p-410070-musical-fantasy.aspx Zaimont, Judith Lang, Pure, Cool (Water) : Symphony No. 4; Piano Trio No. 1 (Russian Summer). 1 sound disc $17.98 4tay Records ©2016 4TAY 4003 2 888295336697 With the Janacek Philharmonic Orchestra; Peter Winograd, violin; Peter Wyrick, cello; Joanne Polk, piano. http://www.tfront.com/p-398594-pure-cool-water-symphony-no-4-piano-trio-no-1-russian-summer.aspx Aca Records Trios For Viola d'Amore and Flute.