Exhausting a Square in Sarajevo

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

SARAJEVO in the WILDERNESS of POST- SOCIALIST TRANSITION: the NEOLIBERAL URBAN TRANSFORMATION of the CITY IS B N: 978 - 88 96951 23 1

PECOB’S VOLUMES N: 978 - 88 96951 23 1 B SARAJEVO IN THE WILDERNESS OF POST- SOCIALIST TRANSITION: THE NEOLIBERAL URBAN TRANSFORMATION OF THE CITY IS Cecilia Borrini European Regional Master’s Programme in Democracy and Human Rights in South East Europe GRADUATION THESIS Portal on Central Eastern and Balkan Europe University of Bologna - Forlì Campus www.pecob.eu SARAJEVO IN THE WILDERNESS OF POST- SOCIALIST TRANSITION: THE NEOLIBERAL URBAN TRANSFORMATION OF THE CITY Cecilia Borrini European Regional Master’s Programme in Democracy and Human Rights in South East Europe Graduation thesis Table of Contents Abstract ..................................................................................................... 7 Keywords ................................................................................................... 7 Introduction ............................................................................................... 9 1. Cities: Key Sites for the Economic Growth and Contestation ................ 13 1.1 A Lefebvrian Approach to the City: the Urban Claim for the Right to the City ................................................................................ 13 1.2 The Current Phase of Capitalism: Neoliberalism and Globalization ....................................................... 19 1.3 The Contemporary Revival of the Right to the City: A Claim against Neoliberalism ........................................................... 22 2. Urban development trends in Central and South Eastern Europe ......... 27 2.1 The Post-Socialist -

2018-12-14 Thesis Final Version

MEMORY, SPACE & LAW MEMORY SITES OF THE 1992-1995 WAR IN PRESENT DAY BOSNIA & HERZEGOVINA AND THE INTEGRATION OF THE ICTY LEGACY. Scientific article Word count: 9.485 Aurore Vanliefde Student number: 01708804 Promotor: Dr. David Mwambari Master’s thesis presented for obtaining the degree of Master in Conflict and Development Academic year: 2018-2019 MEMORY, SPACE & LAW. MEMORY SITES OF THE 1992-1995 WAR IN BOSNIA AND HERZEGOVINA AND THE INTEGRATION OF THE ICTY LEGACY. Abstract This article revolves around memorialisation of the 1992-1995 war in Bosnia and Herzegovina (BiH). Theoretical insights from literature are combined with empirical data from 29 memory sites in BiH, two expert interviews, and additional information from informal conversations with guides and participation in guided tours. The aim of this study is to understand the use of memory sites of the 1992-1995 war in BiH, and research the extent to which the International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia (ICTY)’s legacy has been integrated into these memory sites. The findings show that memorialisation is on-going through the creation, conservation, accentuation and destruction of memory sites. Memorials are generally exclusively meant for one ethno-national group, and are often the product of local and/or private initiatives. These sites of memory are lieux de mémoire, as described by Pierre Nora, where a community’s collective memory is both materialised and generated. Personal testimonies are extensively used in museums and archival material from the ICTY is included in some memory sites. The ICTY’s legacy constitutes a unique kind of memory, a lieu de mémoire sui generis. -

The Silk Road

The Silk Road Volume 1 Number 1 January 15, 2003 第1卷 第1號 “The Bridge between Eastern and Western Cultures” 一月十五日 In This Issue • WELCOME TO THE FIRST ISSUE WELCOME TO THE FIRST ISSUE! • [email protected]: A YE- Since the Soviet collapse, the nations of Central One reason for our distorted image of Central MENI TRADING LINK THREE THOUSAND Asia have shaken off imposed obscurity to make Asia has been the diffi culty of access for west- YEARS OLD headlines of their own. The emergence of these ern travelers, scholars, and archaeologists. new states has helped to focus attention once Russian and Chinese investigators working in • THE ORIGIN OF CHESS AND THE SILK again on their history, culture, and people. For their respective languages have done most of ROAD most of us, these were places whose names we the fi rst hand observation and reporting. The barely knew a decade ago. Collectively more experienced fi eld archaeologists • THE MONGOLS AND THE SILK ROAD they form the heart of Eurasia. Today in Russia and China—Elena Kuzmina • AGE OF MONGOLIAN EMPIRE: A BIB- they may be known as Ukraine, Armenia, from Moscow and Wang Binghua from LIOGRAPHICAL ESSAY Georgia, Azerbaijan, Turkmenistan, Urumchi, for example—have more di- Kazakhstan, Tajikistan, Uzbekistan, and rect experience with Central Asian sites Kyrghizstan, but in the more remote and materials than practically all of past, along with Afghanistan, Xinjiang, the American investigators combined. and Gansu, they evoked images of the an- Their reports and publications, in Russian and cient Silk Road—oases, caravanserai, nomads, Chinese, are available in the west to only a lim- strange empires, fantastic beasts, and exotic ited number of specialists. -

Art Institutions and National Identity in a Post - Conflict Society

Trinity College Trinity College Digital Repository Senior Theses and Projects Student Scholarship Spring 2015 Art Institutions and National Identity in a Post - Conflict Society Pooja Savansukha Trinity College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalrepository.trincoll.edu/theses Part of the Political Theory Commons Recommended Citation Savansukha, Pooja, "Art Institutions and National Identity in a Post - Conflict Society". Senior Theses, Trinity College, Hartford, CT 2015. Trinity College Digital Repository, https://digitalrepository.trincoll.edu/theses/444 ART INSTITUTIONS AND NATIONAL IDENTITY IN A POST-CONFLICT SOCIETY A thesis presented by Pooja Savansukha to The Political Science Department in partial fulfillment of the requirements for Honors in Political Science Trinity College Hartford, CT April 20, 2015 Thesis Advisor Department Chair Art institutions and national identity in a post-conflict society How can art institutions address past mass atrocity, and what does this reveal about the relationship between art and politics in post- conflict societies? A case study of the role of art institutions in post-war Bosnia and Herzegovina Abstract Post-conflict societies inhabit a prolonged identity crisis. This crisis defines the scenario in present day Bosnia and Herzegovina, where ethno-centric narratives embody the consciousness of the Bosniak, Croat, and Serb populations, inhibiting the prevalence of an overarching national identity. In this thesis, I contend that realizing a national identity, as defined by Benedict Anderson, is crucial to the reconciliation of a post-conflict country such as Bosnia. In light of the limitations of parliamentary structures (such as those defined by Bosnia’s Dayton Agreement) within a society affected by mass atrocity, I argue that art institutions are capable of negotiating the question of a national identity. -

PANORAMIC Bos

IMPORTANT PHONE NUMBERS SARAJEVO Ambulance: 124, Police: 123, Fire Department: 123, Road Assistance: 1282, Tel. Number Directory: 1182, Taxi: 1515 Area: 141.5 km², Altitude: 500 m, Climate: Moderate continental climate, Population: 438.000, BiH Country Code: +387, Sarajevo Area Code: (0)33, Airport: 289 100, Bus Station: 213 100, Railway Station: 655 330, Time zone: Central European Time Zone (GMT + 1), Postal code: 71000 PANORAMa Lukavica Bus Station: 057 317 377 Sarajevo Tourism Association of Canton Sarajevo Dalmatinska 2/4 Sarajevo Bosnia and Herzegovina +387 33 252 000 USEFUL INFO [email protected] www.visitsarajevo.ba @www.visitsarajevo.ba @visitsarajevo.ba Public transport: 1.80KM per ride (Buy your ticket from the driver), Cost of Taxi: 1.50KM start + 1KM per km, Currency: 1€ =1,9558KM (Convertible Mark BAM), Tap water: Safe to drink, Electricity: 220V, AC 50Hz VALID TAXI CAR REG. PLATES VALID NON-VALID 102 107 Bolnička Koševo Hospital M18 BREKA Bolnička Zetra & Koševo 8 Olympic hall&stadium Patriotske lige Patriotske 1 2 3 4 Bjelave BJELAVE Ploča VRATNIK CIGLANE Koševo KOVAČI 6 Carina Alipašina Sarajevo Katedrala Baščaršija 1 Željeznička stanica MEJTAŠ 1,2,3 1,2,3 POFALIĆI Train & Bus Station 1,4 Park Banka Miljacka 1,2,3 5 1,2,3 2 2,5km Sarači General Hospital Airport Bus NOVO SARAJEVO Ferhadija Put života Kranjčevićeva Vijećnica Branilaca Sarajeva 1,2,3 M-5 Jahorina Adema Buće Univerzitet Muzej Next bike City bus Skenderija Olympic Mountain Drinska 2,3,4,6 1,2,3,6 station Latinska ćuprija BOLJAKOV POTOK 6 1,2,3 Pofalići Drvenija SARAJEVO 2,3,4,6 Skenderija Pošta 101 Trg Austrije SARAJEVO SARAJEVO Emergency 1,2,3 Bistrik SARAJEVO Vrbanja Marijin dvor 1,2,3 1,2,3 103 104 Cable Car BAČIĆI DOLAC MALTA Socijalno 1,2,3,6 Start staro jevrejsko 2,3,4,6 ž j k Dolac malta SKENDERIJA Terezija 2,3,4,6 Vilsonovo šetalište BISTRIK .. -

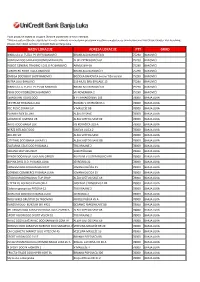

Spisak Za Kupovinu Na Rate

Popis prodajnih mjesta sa uslugom Obročne otplate bez kamata i naknada. *Plaćanje putem Obročne otplate bez kamata i naknada na navedenim prodajnim mjestima omogućeno je svim korisnicima Visa Classic Charge i Visa Revolving (Classic, Net i Gold) karticom UniCredit Bank ad Banja Luka. NAZIV LOKACIJE ADRESA LOKACIJE PTT GRAD BINGO d.o.o. TUZLA PJ 19 FIS BANOVIĆI BRANILACA BANOVIĆA B 75290 BANOVIĆI KONZUM DOO SARAJEVO KONZUM BIH K326 ALIJE IZETBEGOVIĆA 61 75290 BANOVIĆI ROBOT GENERAL TRADING CO D.O PC BANOVIĆI ARMIJE BIH 6A 75290 BANOVIĆI EUROHERC PODR TUZLA BANOVIĆI BRANILACA BANOVIĆI 4 75290 BANOVIĆI OMEGA DOO BEKO SHOP BANOVIĆI BOŽIĆKA BANOVIĆA 6-novi Tržni centar 75290 BANOVIĆI ASTRA DOO BANOVIĆI 119 MUSL BRD BRIGADE 15 75290 BANOVIĆI BINGO d.o.o. TUZLA PJ 23 SM BANOVIĆI BRANILACA BANOVIĆA B 75290 BANOVIĆI PEKO DOO PODRUŽNICA BANOVIĆI VII NOVEMBRA 2 75290 BANOVIĆI SEBASTIJAN TOURS DOO K P I KARAÐORÐEV 103 78000 BANJA LUKA CENTRUM TR BANJA LUKA BUDŽAK V.OSTROŠKOG 1 78000 BANJA LUKA KEC PUŠIĆ ZORAN S.P. V MASLEŠE BB 78000 BANJA LUKA PLANIKA FLEX B.LUKA ALEJA SV SAVE 78000 BANJA LUKA JAĆIMOVIĆ JUVENTA UR ALEJA SVETOG SAVE 69 78000 BANJA LUKA ARTIST DOO BANJA LUK I G KOVAČIĆA 203-A 78000 BANJA LUKA NERZZ BEŠLAGIĆ DOO GAJEVA ULICA 2 78000 BANJA LUKA AB LINE SIX ALEJA SVETOG SAVE 78000 BANJA LUKA CITYTIME DOO BANJA LUKA PJ 1 ALEJA SVETOG SAVE BB 78000 BANJA LUKA ZLATARNA CELJE DOO PJ BANJA L TRG KRAJINE 2 78000 BANJA LUKA VERANO MOTORS RENT SUBOTIČKA BB 78000 BANJA LUKA DEKOR DOO BANJA LUKA MALOPROD BULEVAR V S STEPANOVIĆA BB 78000 BANJA LUKA ALPINA BH D.O.O. -

Godišnji Izvještaj Za 2016

EDUS- Godišnji izvještaj za 2016. GODIŠNJI 2016. IZVJEŠTAJ [NARATIVNI GODIŠNJI IZVJEŠTAJ] [Pregled najvažnijih aktivnosti, projekata i postignuća organizacije EDUS-Edukacija za sve u 2016. godini.] Mjedenica 34, 71000 Sarajevo [email protected] www.edusbih.org EDUS- Godišnji izvještaj za 2016. SADRŽAJ: 1. KRATAK PREGLED GLAVNIH DEŠAVANJA ..........................................................2 1.1. PRESJEK SVIH ŠEST GODINA EDUS-a.............................................................2 1.2. KRATAK PREGLED AKTIVNOSTI U 2016-oj ......................................................3 2. RAD S DJECOM PO NAUČNOJ METODOLOGIJI....................................................4 2.1. EDUS UČIONICE I VRTIĆKE GRUPE U OKVIRU ZAVODA MJEDENICA.....8 2.2. PROGRAM RANE INTERVENCIJE..................................................................9 2.3. DOPUNSKA NASTAVA..................................................................................10 2.4. LJETNA ŠKOLA..............................................................................................10 3. EDUKACIJA STRUČNJAKA.....................................................................................11 3.1. EDUKACIJA KROZ RAD U EDUS PROGRAMU............................................11 3.2. EDUKACIJA STRUČNJAKA ŠIROM BIH KROZ PROJEKAT S UNICEF-om I FEDERALNIM MINISTARSTVOM ZDRAVSTVA............................................11 3.3. TERCIJARNO OBRAZOVANJE EDUS-OVIH STRUČNJAKA U INOSTRANSTVU............................................................................................14 -

Neo-Liberalism, the Islamic Revival, and Urban Development in Post-War, Post-Socialist Sarajevo

Neo-Liberalism, the Islamic Revival, and Urban Development in Post-War, Post-Socialist Sarajevo By Zev Moses A thesis submitted in conformity with the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Geography Department of Geography and Program in Planning University of Toronto © Copyright by Zev Moses 2012 Neo-Liberalism, the Islamic Revival, and Urban Development in Post-War, Post-Socialist Sarajevo Zev Moses Master of Arts in Geography Department of Geography and Program in Planning University of Toronto 2012 Abstract This thesis examines the confluence between pan-Islamist politics, neo-liberalism and urban development in Sarajevo, Bosnia and Herzegovina. After tracing a history of the Islamic revival in Bosnia, I examine the results of neo-liberal policy in post-war Bosnia, particularly regarding the promises of neo-liberal institutions and think tanks that privatization and inflows of foreign direct investment (FDI) would de-politicize the economy and strip ethno-religious nationalist elites of their power over state-owned firms. By analyzing three prominent new urban developments in Sarajevo, all financed by FDI from the Islamic world and brought about by the privatization of urban real-estate, I show how neo-liberal policy has had unintended outcomes in Sarajevo that contradict the assertions of policy makers. In examining urban change, I bring out the role played by the city in mediating between both elites and citizens, and between the seemingly contradictory projects of pan-Islamism and neo- liberalism. ii Acknowledgements I would like to extend my gratitude to everyone who helped me in one way or another with this project. -

Sarajevo Redux: Socio-Spatial Outcomes and the Perpetuation of Fragility in a Post- Conflict City

Sarajevo Redux: Socio-Spatial Outcomes and the Perpetuation of Fragility in a Post- Conflict City James Schmitt Supervisor: Prof. Günter Meinert Supervisor: Prof. Dr.-Ing. Philipp Misselwitz Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of Master of Science in Urban Management at Technische Universität Berlin Berlin, 1st of February 2019 Statement of authenticity of material This thesis contains no material which has been accepted for the award of any other degree or diploma in any institution and to the best of my knowledge and belief, the research contains no material previously published or written by another person, except where due reference has been made in the text of the thesis. James D. Schmitt Berlin, 1 February 2019 Abstract In an increasingly urbanized world, new constructs concerning urban fragility, the changed nature and increasing urbanization of armed conflict and emerging conceptual frameworks for urban post-conflict interventions present new discourses for urban planners and post-conflict first responders to consider. Cities with the highest level of fragility tend to be in states destabilized by ongoing intrastate conflict and yet even after negotiated peace settlements recovering cities appear particularly vulnerable to the accumulation of urban risks and tensions associated with higher levels of urban fragility. Working as part of an international post-conflict intervention recovery effort, how can urban planners contribute to achieving better long-term outcomes of peace and stability in the urban post-conflict setting? By conducting a macro and meso level case study analysis of Sarajevo's international post- conflict intervention through the lens of the social contract, liberal peace, and collective memory theoretical frameworks, this thesis seeks to identify strategic approaches and outcomes of Sarajevo's post-conflict intervention process and the related long-term impacts of these outcomes at the municipal and neighborhood scale. -

Sarajevo, Bosnia and Herzegovina

https://www.thesaturdaypaper.com.au/2016/08/27/sarajevo‐bosnia‐and‐ herzegovina/14722200003650?utm_campaign=Contact+SNS+For+More+Referrer&utm_medium=twi tter&utm_source=snsanalytics TRAVEL AUG 27, 2016 Sarajevo, Bosnia and Herzegovina LINDA JAIVIN Sarajevo’s streets bear the scars of the Bosnian War siege, but people are pursuing a relaxed approach to life. Dimitri Kruglikov Čajdžinica Džirlo in Sarajevo, Bosnia and Herzegovina. The muezzin’s call to prayer drifts up the hill to the teahouse, as ethereal as the wispy clouds that float in the luminous summer sky. As the call dies away, Hussein, a man with a great mane of white hair and a charismatic, California-grade smile, puts on music threaded with the unearthly vibrations of a theremin. Down the cobblestone street, the Ottoman Old Town appears a jumble of burnt-orange roofs clustering around a small turquoise dome in the middle of a modest square. Within Hussein’s teahouse, Čajdžinica Džirlo, there are hints of Turkey in the woven pillows and rugs and of Europe in the lacy table doilies. Arrayed at the front of the shop next door is a collection of objects crafted from pale, unvarnished wood: clogs, broom handles, crutches, a butter churn. The delicate almond and rose petal aroma of my chai mingles with the sharper smells of rich Bosnian coffee and acrid cigarettes from adjoining tables. Public smoking is still a thing in Sarajevo. It may not be a great idea for public health, but it certainly lends the place an appealingly raffish air, and adds to the sense of it belonging to an older world, one that is at once rustic, small town and cosmopolitan, that moves to its own languid pace. -

Geopolitical and Urban Changes in Sarajevo (1995 – 2015)

Geopolitical and urban changes in Sarajevo (1995 – 2015) Jordi Martín i Díaz Aquesta tesi doctoral està subjecta a la llicència Reconeixement- NoComercial – SenseObraDerivada 3.0. Espanya de Creative Commons. Esta tesis doctoral está sujeta a la licencia Reconocimiento - NoComercial – SinObraDerivada 3.0. España de Creative Commons. This doctoral thesis is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial- NoDerivs 3.0. Spain License. Facultat de Geografia i Història Departament de Geografia Programa de Doctorat “Geografia, planificació territorial i gestió ambiental” Tesi doctoral Geopolitical and urban changes in Sarajevo (1995 – 2015) del candidat a optar al Títol de Doctor en Geografia, Planificació Territorial i Gestió Ambiental Jordi Martín i Díaz Directors Dr. Carles Carreras i Verdaguer Dr. Nihad Čengi ć Tutor Dr. Carles Carreras i Verdaguer Barcelona, 2017 This dissertation has been funded by the Program Formación del Profesorado Universitario of the Spanish Ministry of Education, fellowship reference (AP2010- 3873). Als meus pares i al meu germà. Table of contents Aknowledgments Abstract About this project 1. Theoretical and conceptual approach 15 Socialist and post-socialist cities 19 The question of ethno-territorialities 26 Regarding international intervention in post-war contexts 30 Methodological approach 37 Information gathering and techniques 40 Structure of the dissertation 44 2. The destruction and division of Sarajevo 45 Sarajevo: common life and urban expansion until early 1990s 45 The urban expansion 48 The emergence of political pluralism 55 Towards the ethnic division of Sarajevo: SDS’s ethno-territorialisation campaign and the international partiality in the crisis 63 The Western policy towards Yugoslavia: paving the way for the violent ethnic division of Bosnia 73 The siege of Sarajevo 77 Deprivation, physical destruction and displacement 82 The international response to the siege 85 SDA performance 88 Sarajevo’s ethno-territorial division in the Dayton Peace Agreement 92 The DPA and the OHR’s mission 95 3. -

Zeleni Akcioni Plan Kantona Sarajevo Studija O Urbanim Ventilacionim Koridorima I Uticaju Visokih Zgrada Evropska Banka Za Obnovu I Razvoj

Zeleni akcioni plan Kantona Sarajevo Studija o urbanim ventilacionim koridorima i uticaju visokih zgrada Evropska banka za obnovu i razvoj Decembar 2019. Napomena Ovaj dokument i njegov sadržaj pripremljeni su i namijenjeni isključivo kao informacija za Evropsku banku za obnovu i razvoj (EBRD) i Kanton Sarajevo i za potrebe projekta Zeleni akcioni plan Kantona Sarajevo koji se priprema po metodološkom okviru zelenih gradova EBRD-a. Svi stavovi, mišljenja, pretpostavke, izjave i preporuke iskazani u ovom dokumentu pripadaju WS Atkins International Limited i ne odražavaju nužno službenu politiku ili stav Kantona Sarajevo. EBRD i Kanton Sarajevo ne prihvataju nikakvu odgovornost u pogledu bilo kakvih potraživanja od trećih strana direktno ili indirektno povezanih sa ulogom EBRD-a u odabiru i angažmanu ili praćenju rada WS Atkins International Limited, odnosno posljedicama korištenja i oslanjanja na usluge WS Atkins International Limited. Izradu ovog dokumenta je finansirala Vlada Japana uz provedbu putem EBRD-a. WS Atkins International Limited ne prihvata odgovornost u odnosu na bilo koju stranu u pogledu ovog dokumenta, odnosno sadržaja istog, ili odgovornost koja je nastala iz istog ili je u vezi s njim. Ovaj dokument ima 75 stranica, uključujući naslovnu stranicu. Historijat dokumenta Revidiran Opis svrhe Kreiran Provjeren Pregledan Odobren Datum 1.1. Nacrt izvještaja SMK, MuH CGL MH SF 17.10.2019. godine 2.3. Revidirani izvještaj SMK, MuH CGL, MH SF 6.12.2019. SMK godine Odobrenje korisnika Korisnik <Evropska banka za obnovu i razvoj> Projekat <Zeleni akcioni plan Kantona Sarajevo> – Studija o urbanim ventilacionim koridorima Broj zaduženja 5183282 Potpis korisnika / datum Contains private information EBRD _ GCAP_ Study on urban ventilation corridors_BiH_27.01_Final i uticaju visokih zgrada Strana: 2 Sadržaj NAPOMENA .......................................................................................................................................