Archaeology & Archaeologically Sensitive Areas

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

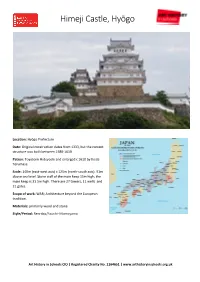

Himeji Castle, Hyōgo

Himeji Castle, Hyōgo Location: Hyōgo Prefecture Date: Original construction dates from 1333, but the current structure was built between 1580-1610 Patron: Toyotomi Hideyoshi and enlarged c 1610 by Ikeda Terumasa. Scale: 140m (east-west axis) x 125m (north-south axis). 91m above sea level. Stone wall of the main keep 15m high; the main keep is 31.5m high. There are 27 towers, 11 wells and 21 gates. Scope of work: WAR; Architecture beyond the European tradition. Materials: primarily wood and stone Style/Period: Renritsu/Azuchi–Momoyama Art History in Schools CIO | Registered Charity No. 1164651 | www.arthistoryinschools.org.uk Himeji Castle, Hyōgo Introduction Japan’s most magnificent castle, a Unesco World Heritage Site and one of only a handful of original castles remaining. Nicknamed the ‘White Egret Castle’ for its spectacular white exterior and striking shape emerging from the plain. Himeji is a hill castle, that takes advantage of the surrounding geography to enhance its defensive qualities. There are three moats to obstruct the enemy and 15m sloping stone walls make approaching the base of the castle very difficult. Formal elements Viewed externally, there is a five-storey main tenshu (keep) and three smaller keeps, all surrounded by moats and defensive walls. These walls are punctuated with rectangular openings (‘sama’) for firing arrows and circular and triangular openings for guns. These ‘sama’ are at different heights to allow for the warrior to be standing, kneeling or lying down. The main keep’s walls also feature narrow openings that allowed defenders to pour boiling water or oil on to anyone trying to scale the walls. -

Merthyr Tydfil County Borough Council Planning & Neighbourhood

Merthyr Tydfil County Borough Council Planning & Neighbourhood Services Engineering February 2020 Flood Damage Maps 1) Flood recovery costs spreadsheet 2) Flood damage locations by ward maps 3) Detailed flood damage area maps 3rd May 2020 Ref Location Detail Action/programme Capital / Estimated Cost (£) Revenue 2020-21 2021-22 1 Bedlinog Cemetery Landslide Drainage and Capital 200,000 Road stabilisation work 2 Pant Glas Fawr, Damaged culvert Culvert repairs Capital 70,000 Aberfan 3 Walters Terrace, Damaged culvert Culvert repairs Capital 70,000 Aberfan 4 Chapel Street Landslide Drainage and Capital 80,000 Treodyrhiw stabilisation work 5 Grays Place, Merthyr Collapsed culvert Replace culvert Capital 120,000 Vale 6 Maes y Bedw, Bedlinog Damaged culvert Replace culvert Capital 50,000 7 Nant yr Odyn, Damaged culvert Culvert repairs Capital 50,000 Troedyrhiw 8 Park Place, Troedyrhiw Damaged culvert Culvert repairs Capital 20,000 9 Cwmdu Road, Landslide Drainage and Capital 40,000 Troedyrhiw stabilisation work 10 Fiddlers Elbow, Damaged debris Repair of trash screen Capital 5,000 Quakers Yard screen 11 Pontycafnau River embankment Reinstate embankment Capital 250,000 erosion and scour protection 12 Harveys Bridge, Piers undermined Remove debris with Capital 30,000 Quakers Yard scour protection 13 Taff Fechan Landslide Drainage and Capital 80,000 stabilisation work 14 Mill Road, Quakers River embankment Remove tree and Capital 60,000 Yard erosion stabilise highway 15 Nant Cwmdu, Damaged culvert Culvert repairs Capital 40,000 Troedyrhiw 16 Nant -

Hoover Site, Pentrebach Strategic Transport Assessment

Hoover Site, Pentrebach Strategic Transport Assessment October 2018 Mott MacDonald Mott MacDonald House 8-10 Sydenham Road Croydon CR0 2EE United Kingdom T +44 (0)20 8774 2000 F +44 (0)20 8681 5706 mottmac.com Hoover Site, Pentrebach 367590KC03 1 B P:\Cardiff\ERA\ITD\Projects\367590 BNI Cardiff Metro\Task Order 044 Hoover Site\03 Strategic TransportReports\Hoover Transport Assessment Assessment v4.docx Mott MacDonald October 2018 Mott MacDonald Group Limited. Registered in England and Wales no. 1110949. Registered office: Mott MacDonald House, 8-10 Sydenham Road, Croydon CR0 2EE, United Kingdom Mott MacDonald | Hoover Site, Pentrebach Strategic Transport Assessment Issue and Revision Record Revision Date Originator Checker Approver Description A Aug 2018 M Henderson S Arthur DRAFT for comment. B Oct 2018 M Henderson S Arthur D Chaloner FINAL issue Document reference: 367590KC03 | 1 | B Information class: Standard This document is issued for the party which commissioned it and for specific purposes connected with the above- captioned project only. It should not be relied upon by any other party or used for any other purpose. We accept no responsibility for the consequences of this document being relied upon by any other party, or being used for any other purpose, or containing any error or omission which is due to an error or omission in data supplied to us by other parties. This document contains confidential information and proprietary intellectual property. It should not be shown to other parties without consent from us and from the party which commissioned it. This Re por t has be en p rep are d solely for use by t he p arty w hich c om mission ed it (the 'Client') i n co nnecti on wit h the cap tione d p roject . -

Canolfan Llywodraethiant Cymru Paper 5A - Wales Governance Centre

Papur 5a - Canolfan Llywodraethiant Cymru Paper 5a - Wales Governance Centre DEPRIVATION AND IMPRISONMENT IN WALES BY LOCAL AUTHORITY AREA SUPPLEMENTARY EVIDENCE TO THE NATIONAL ASSEMBLY’S EQUALITY, LOCAL GOVERNMENT AND COMMUNITIES COMMITTEE’S INQUIRY INTO VOTING RIGHTS FOR PRISONERS DR GREG DAVIES AND DR ROBERT JONES WALES GOVERNANCE CENTRE AT CARDIFF UNIVERSITY MAY 2019 Papur 5a - Canolfan Llywodraethiant Cymru Paper 5a - Wales Governance Centre ABOUT US The Wales Governance Centre is a research centre that forms part of Cardiff University’s School of Law and Politics undertaking innovative research into all aspects of the law, politics, government and political economy of Wales, as well the wider UK and European contexts of territorial governance. A key objective of the Centre is to facilitate and encourage informed public debate of key developments in Welsh governance not only through its research, but also through events and postgraduate teaching. In July 2018, the Wales Governance Centre launched a new project into Justice and Jurisdiction in Wales. The research will be an interdisciplinary project bringing together political scientists, constitutional law experts and criminologists in order to investigate: the operation of the justice system in Wales; the relationship between non-devolved and devolved policies; and the impact of a single ‘England and Wales’ legal system. CONTACT DETAILS Wales Governance Centre at Cardiff University, 21 Park Place, Cardiff, CF10 3DQ. Web: http://sites.cardiff.ac.uk/wgc/ ABOUT THE AUTHORS Greg Davies is a Research Associate at the Wales Governance Centre at Cardiff University. His PhD examined the constitutional relationship between the UK courts and the European Court of Human Rights. -

Advice to Inform Post-War Listing in Wales

ADVICE TO INFORM POST-WAR LISTING IN WALES Report for Cadw by Edward Holland and Julian Holder March 2019 CONTACT: Edward Holland Holland Heritage 12 Maes y Llarwydd Abergavenny NP7 5LQ 07786 954027 www.hollandheritage.co.uk front cover images: Cae Bricks (now known as Maes Hyfryd), Beaumaris Bangor University, Zoology Building 1 CONTENTS Section Page Part 1 3 Introduction 1.0 Background to the Study 2.0 Authorship 3.0 Research Methodology, Scope & Structure of the report 4.0 Statutory Listing Part 2 11 Background to Post-War Architecture in Wales 5.0 Economic, social and political context 6.0 Pre-war legacy and its influence on post-war architecture Part 3 16 Principal Building Types & architectural ideas 7.0 Public Housing 8.0 Private Housing 9.0 Schools 10.0 Colleges of Art, Technology and Further Education 11.0 Universities 12.0 Libraries 13.0 Major Public Buildings Part 4 61 Overview of Post-war Architects in Wales Part 5 69 Summary Appendices 82 Appendix A - Bibliography Appendix B - Compiled table of Post-war buildings in Wales sourced from the Buildings of Wales volumes – the ‘Pevsners’ Appendix C - National Eisteddfod Gold Medal for Architecture Appendix D - Civic Trust Awards in Wales post-war Appendix E - RIBA Architecture Awards in Wales 1945-85 2 PART 1 - Introduction 1.0 Background to the Study 1.1 Holland Heritage was commissioned by Cadw in December 2017 to carry out research on post-war buildings in Wales. 1.2 The aim is to provide a research base that deepens the understanding of the buildings of Wales across the whole post-war period 1945 to 1985. -

A465 Abergavenny Hirwaun A4060 East of Abercynon East of Dowlais

THE WELSH MINISTERS (THE NEATH TO ABERGAVENNY TRUNK ROAD (A465) (ABERGAVENNY TO HIRWAUN DUALLING AND SLIP ROADS AND EAST OF ABERCYNON TO EAST OF DOWLAIS TRUNK ROAD (A4060) CARDIFF TO GLAN CONWY TRUNK ROAD (A470) (CONNECTING ROADS) (DOWLAIS TOP TO HIRWAUN)) (SUPPLEMENTARY) (No.1) COMPULSORY PURCHASE ORDER 2020 The Schedule References to ownership are reference to ownership or reputed ownership at the time of preparation of the Supplementary Order and are stated only for the purpose of identification of the land. In Column 2 of this schedule the OS Nos (Ordnance Survey Enclosure Numbers) are the numbers given on the 1:2500 Ordnance Survey Sheet Nos. as follows: SN9406 (A) SN9605 (F) SN9807 (J) SN9906 (N) SO0207 (S) SO0608 (AE) SO0908 (AM) SN9405 (B) SN9604 (G) SN9806 (K) SO0007 (O) SO0208 (U) SO0708 (AH) SO0909 (AN) SN9505 (D) SN9705 (H) SN9805 (L) SO0006 (P) SO0308 (W) SO0808 (AJ) SN9504 (E) SN9706 (I) SN9907 (M) SO0107 (Q) SO0408 (Y) SO0809 (AL) Where OS Enclosure Numbers are unavailable, reference numbers containing 4 digits and the prefix “A-” have been substituted. Where the Enclosure Number straddles two OS sheets, the earlier alphabetical letter has been used. The following approximate imperial equivalents relate to the metric measurements used in the accompanying drawings and schedules; Units of length: 1mm = 0.039 inches (approx.) 1 metre = 1.094 yards (approx.) 1km = 0.621 miles (approx.) Units of area: 1 sq.m. = 1.196 sq. yards (approx.) 1 SCHEDULE 1 LAND TO BE PURCHASED (EXCEPT EXCHANGE LAND) AND NEW RIGHTS Table 1 Number Extent, -

Viking River Cruises 2018

VIKING RIVER CRUISES 2018 River Cruise Atlas Brochure 2018.indd 1 28/02/2017 08:44 2 River Cruise Atlas Brochure 2018.indd 2 28/02/2017 08:44 explore in Viking comfort In Norway they call it koselig. In Denmark, hygge. At Viking we simply call it comfort. And we believe it’s the only way to explore the world. Comfort is knowing that you are completely cared for in every way. It’s a glass of wine under a starlit sky. Good food in the company of good friends. Sinking in to a delicious king-sized bed and surrendering to the deepest of sleeps. It’s a feeling of contentment and wellbeing. Comfort is togetherness, a generosity of spirit and a very real sense of belonging. We hope that you enjoy browsing this brochure and find all the inspiration you need to explore the world in comfort with Viking during 2018. Call us on 0800 810 8220 3 River Cruise Atlas Brochure 2018.indd 3 28/02/2017 08:44 why Viking The world is an amazing place and we believe you deserve to see, hear, taste and touch it all. As an independently owned company, we are able to do things differently, to create journeys where you can immerse yourself in each destination, and explore its culture, history and cuisine. Our decades of experience give us an unrivalled level of expertise. And, with the largest, most innovative fleet of ships in the world, we are consistently voted best river cruise line by all the major players, including the British Travel Awards, Cruise International Awards and Times Travel Awards. -

In the Lead Cyfarthfa High School Newsletter

IN THE LEAD CYFARTHFA HIGH SCHOOL NEWSLETTER MAY 2021 No. 5 STUDENTS FUELLED WITH SUCCESS! FROM THE HEAD’S DESK As Covid-19 restrictions continue to ease across the country, it has been a pleasure to see the return of students to school for a full term. Although we’re still doing things differently, our commitment to providing the very highest standard of education to our students remains unwavering. We realise there’s still a long way to go before normality resumes, but this term has illustrated what staff and students Cyfarthfa High School students attended a university can achieve by working together. graduation ceremony after completing a hydrogen fuel project with flying colours. One of our biggest concerns this term Six of our Year 9 pupils graduated from the Scholar's Programme. has been that of attendance. With the They have worked with a PhD tutor over the last few months on a return to school measures implemented project relating to hydrogen fuel and completed their final after disjointed periods of lockdown, it assignment with excellent results. is essential that we tackle truancy and They recently took part in an online graduation ceremony from punctuality. Warwick University. __________________________________________________________ Your child’s attendance will affect the number of GCSEs they will pass at grade High Sheriff’s Gratitude to School C or above. Children with over 90% The High Sheriff of Mid Glamorgan has recognised the attendance to school are more likely to incredible commitment by teachers of Cyfarthfa High School gain 5 or more A* to C GSCEs or equivalent qualifications. -

Reference Code: GB 214 UDMT

GLAMORGAN RECORD OFFICE/ARCHIFDY MORGANNWG Reference code: GB 214 UDMT Title: MERTHYR TYDFIL URBAN DISTRICT COUNCIL Date(s) 1895-1903 Level of description: Fonds (level 2) Extent: 0.03 cubic metres Name of creator(s) Merthyr Tydfil Urban District Council SOME OF THE RECORDS ARE STORED IN AN OUTSIDE REPOSITORY. THESE RECORDS SHOULD BE ORDERED AT LEAST A WEEK IN ADVANCE OF AN INTENDED VISIT SO THAT THEY CAN BE BROUGHT INTO THE RECORD OFFICE FOR CONSULTATION IN THE SEARCH ROOM Administrative/Biographical history Merthyr Tydfil Urban District Council was formed in 1894 following the Local Government England and Wales Act. Three councillors were elected for each of the six wards, Cyfarthfa, Dowlais, Town, Penydarren, Plymouth, Merthyr Vale. The council took over the functions of the Merthyr Tydfil Board of Health, in particular responsibility for public health, housing highways and bridges, as well as the taking over the functions of Merthyr and Dowlais Burial Boards. In 1902 the provision of elementary education was transferred to the council from the School Board. Scope and content Merthyr Tydfil Urban District Council records include Council Minutes 1895-1896 and Committee minutes, 1895-1903 Appraisal, destruction and scheduling information All records offered have been accepted and listed Conditions governing access Open Access Conditions governing reproduction Normal Glamorgan Record Office conditions apply Language/Scripts of material English © Glamorgan Record Office MERTHYR TYDFIL URBAN DISTRICT COUNCIL UDMT Physical characteristics -

Merthyr Tydfil Open Space Strategy Action Plan June 2016

Merthyr Tydfil Open Space Strategy Action Plans Miss J. Jones Head of Planning Merthyr Tydfil County Borough Council Unit 5 Triangle Business Park Pentrebach Merthyr Tydfil June 2016 CF48 4TQ Contents Section Page 1.0 INTRODUCTION 2 2.0 BEDLINOG ACTION PLAN1 4 3.0 CYFARTHFA ACTION PLAN 11 4.0 DOWLAIS ACTION PLAN 18 5.0 GURNOS ACTION PLAN 26 6.0 MERTHYR VALE ACTION PLAN 33 7.0 PARK ACTION PLAN 41 8.0 PENYDARREN ACTION PLAN 49 9.0 PLYMOUTH ACTION PLAN 55 10.0 TOWN ACTION PLAN 62 11.0 TREHARRIS ACTION PLAN 69 12.0 VAYNOR ACTION PLAN 77 1 Please note that all maps are Crown copyright and database rights 2015 Ordnance Survey 100025302. You are not permitted to copy, sub-licence, distribute or sell any of this data to third parties in any form. 1 1.0 INTRODUCTION 1.1 This document consists of eleven action plans which support the Open Space Strategy and should be read alongside the main document. The Strategy identifies locally important open spaces, sets the standards for different types of open space and establishes the need for further types of open space. Shortfalls in accessibility, quantity and quality have been established through the application of the standards which can be found in Section 2 of the Open Space Strategy2. 1.2 The Action Plans consider the three standards (Quantity, Quality and Accessibility) at Ward level and identify a series of priority sites where, with the inclusion of additional types of open space within existing provision, need might be fulfilled. -

Railway and Canal Historical Society Early Railway Group

RAILWAY AND CANAL HISTORICAL SOCIETY EARLY RAILWAY GROUP Occasional Paper 251 BENJAMIN HALL’S TRAMROADS AND THE PROMOTION OF CHAPMAN’S LOCOMOTIVE PATENT Stephen Rowson, with comment from Andy Guy Stephen Rowson writes - Some year ago I had access to some correspondence originally in the Llanover Estate papers and made this note from within a letter by Benjamin Hall to his agent John Llewellin, dated 7 March 1815: Chapman the Engineer called on me today. He says one of their Engines will cost about £400 & 30 G[uinea]s per year for his Patent. He gave a bad account of the Collieries at Newcastle, that they do not clear 5 per cent. My original thoughts were of Chapman looking for business by hawking a working model of his locomotive around the tramroads of south Wales until I realised that Hall wrote the letter from London. So one assumes the meeting with William Chapman had taken place in the city rather than at Hall’s residence in Monmouthshire. No evidence has been found that any locomotive ran on Hall’s Road until many years later after it had been converted from a horse-reliant tramroad. Did any of Chapman’s locomotives work on south Wales’ tramroads? __________________________________ Andy Guy comments – This is a most interesting discovery which raises a number of issues. In 1801, Benjamin Hall, M.P. (1778-1817) married Charlotte, daughter of the owner of Cyfarthfa ironworks, Richard Crawshay, and was to gain very considerable industrial interests from his father- in-law.1 Hall’s agent, John Llewellin, is now better known now for his association with the Trevithick design for the Tram Engine, the earliest surviving image of a railway locomotive.2 1 Benjamin Hall was the son of Dr Benjamin Hall (1742–1825) Chancellor of the diocese of Llandaff, and father of Sir Benjamin Hall (1802-1867), industrialist and politician, supposedly the origin of the nickname ‘Big Ben’ for Parliament’s clock tower (his father was known as ‘Slender Ben’ in Westminster). -

Cardiff 19Th Century Gameboard Instructions

Cardiff 19th Century Timeline Game education resource This resource aims to: • engage pupils in local history • stimulate class discussion • focus an investigation into changes to people’s daily lives in Cardiff and south east Wales during the nineteenth century. Introduction Playing the Cardiff C19th timeline game will raise pupil awareness of historical figures, buildings, transport and events in the locality. After playing the game, pupils can discuss which of the ‘facts’ they found interesting, and which they would like to explore and research further. This resource contains a series of factsheets with further information to accompany each game board ‘fact’, which also provide information about sources of more detailed information related to the topic. For every ‘fact’ in the game, pupils could explore: People – Historic figures and ordinary population Buildings – Public and private buildings in the Cardiff locality Transport – Roads, canals, railways, docks Links to Castell Coch – every piece of information in the game is linked to Castell Coch in some way – pupils could investigate those links and what they tell us about changes to people’s daily lives in the nineteenth century. Curriculum Links KS2 Literacy Framework – oracy across the curriculum – developing and presenting information and ideas – collaboration and discussion KS2 History – skills – chronological awareness – Pupils should be given opportunities to use timelines to sequence events. KS2 History – skills – historical knowledge and understanding – Pupils should be given