Deprivation and Imprisonment in Wales by Local Authority Area

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Merthyr Tydfil County Borough Council Planning & Neighbourhood

Merthyr Tydfil County Borough Council Planning & Neighbourhood Services Engineering February 2020 Flood Damage Maps 1) Flood recovery costs spreadsheet 2) Flood damage locations by ward maps 3) Detailed flood damage area maps 3rd May 2020 Ref Location Detail Action/programme Capital / Estimated Cost (£) Revenue 2020-21 2021-22 1 Bedlinog Cemetery Landslide Drainage and Capital 200,000 Road stabilisation work 2 Pant Glas Fawr, Damaged culvert Culvert repairs Capital 70,000 Aberfan 3 Walters Terrace, Damaged culvert Culvert repairs Capital 70,000 Aberfan 4 Chapel Street Landslide Drainage and Capital 80,000 Treodyrhiw stabilisation work 5 Grays Place, Merthyr Collapsed culvert Replace culvert Capital 120,000 Vale 6 Maes y Bedw, Bedlinog Damaged culvert Replace culvert Capital 50,000 7 Nant yr Odyn, Damaged culvert Culvert repairs Capital 50,000 Troedyrhiw 8 Park Place, Troedyrhiw Damaged culvert Culvert repairs Capital 20,000 9 Cwmdu Road, Landslide Drainage and Capital 40,000 Troedyrhiw stabilisation work 10 Fiddlers Elbow, Damaged debris Repair of trash screen Capital 5,000 Quakers Yard screen 11 Pontycafnau River embankment Reinstate embankment Capital 250,000 erosion and scour protection 12 Harveys Bridge, Piers undermined Remove debris with Capital 30,000 Quakers Yard scour protection 13 Taff Fechan Landslide Drainage and Capital 80,000 stabilisation work 14 Mill Road, Quakers River embankment Remove tree and Capital 60,000 Yard erosion stabilise highway 15 Nant Cwmdu, Damaged culvert Culvert repairs Capital 40,000 Troedyrhiw 16 Nant -

Canolfan Llywodraethiant Cymru Paper 5A - Wales Governance Centre

Papur 5a - Canolfan Llywodraethiant Cymru Paper 5a - Wales Governance Centre DEPRIVATION AND IMPRISONMENT IN WALES BY LOCAL AUTHORITY AREA SUPPLEMENTARY EVIDENCE TO THE NATIONAL ASSEMBLY’S EQUALITY, LOCAL GOVERNMENT AND COMMUNITIES COMMITTEE’S INQUIRY INTO VOTING RIGHTS FOR PRISONERS DR GREG DAVIES AND DR ROBERT JONES WALES GOVERNANCE CENTRE AT CARDIFF UNIVERSITY MAY 2019 Papur 5a - Canolfan Llywodraethiant Cymru Paper 5a - Wales Governance Centre ABOUT US The Wales Governance Centre is a research centre that forms part of Cardiff University’s School of Law and Politics undertaking innovative research into all aspects of the law, politics, government and political economy of Wales, as well the wider UK and European contexts of territorial governance. A key objective of the Centre is to facilitate and encourage informed public debate of key developments in Welsh governance not only through its research, but also through events and postgraduate teaching. In July 2018, the Wales Governance Centre launched a new project into Justice and Jurisdiction in Wales. The research will be an interdisciplinary project bringing together political scientists, constitutional law experts and criminologists in order to investigate: the operation of the justice system in Wales; the relationship between non-devolved and devolved policies; and the impact of a single ‘England and Wales’ legal system. CONTACT DETAILS Wales Governance Centre at Cardiff University, 21 Park Place, Cardiff, CF10 3DQ. Web: http://sites.cardiff.ac.uk/wgc/ ABOUT THE AUTHORS Greg Davies is a Research Associate at the Wales Governance Centre at Cardiff University. His PhD examined the constitutional relationship between the UK courts and the European Court of Human Rights. -

Ymyl Yr Afon MERTHYR VALE Ymyl Yr Afon MERTHYR VALE Ymyl Yr Afon, Golwg Yr Afan, Merthyr Vale, Merthyr Tydfil CF48 4QQ T: 01685 868 249

PRESENTS Ymyl Yr Afon MERTHYR VALE Ymyl Yr Afon MERTHYR VALE Ymyl Yr Afon, Golwg Yr Afan, Merthyr Vale, Merthyr Tydfil CF48 4QQ T: 01685 868 249 Ymyl Yr Afon MERTHYR VALE Ymyl Yr @lovell_uk /lovellhomes Afon lovellnewhomes.co.uk MERTHYR VALE WELCOME TO A stunning collection of 2, 3 and 4 bedroom homes situated on a former colliery site between Merthyr Vale and Aberfan, with the River Taff curving to the west of the development, the new community will feature attractive tree-lined streets with plentiful areas of open green space. Merthyr Vale Lovell uses sustainable products wherever possible. So not only do our homes help look after the environment, but for homeowners, they also offer excellently insulated properties, minimal maintenance and they stand the test of time. All of our homes are of extremely high quality and specification. Combining carefully considered contemporary design with rigorous build quality, Lovell homes are designed with flair, character and attention to detail. We want your home to be interesting, inviting and individual. LOVELL LIFE Most of all, once you step through the front door, we want you to know you’re home. Oakfield Grange showhome interior Oakfield Grange showhome interior Oakfield Grange showhome interior Every one of the homes we build is built with one crucial extra element: pride. Lovell only builds high-quality homes and we make customer satisfaction our number one priority. This means that you enjoy extraordinary value for money, as well as a superior and distinctive home. At Lovell we believe your home should be more than about the right place at the right price. -

The Taff Trail Is Just One of a Series of Trails Running Right Rivals the Best in the World

Feel Rested Other Trails in Merthyr Tydfil Aberfan Community Centre Merthyr has plenty of other trails on offer, Located in the centre of the village. so why not try one of these? The Open: 8am-8pm Mon - Fri and 9am – 4pm Sat & Sun. P Key Taff Trail (Route 8) Taff Trail Merthyr Tydfil Leisure Centre Trevithick Trail Located in Merthyr’s Leisure Village, just (Route 477) Merthyr Tydfil a short walk from the town centre. Celtic Trail (Route 4) Open: 8am-8pm Mon - Fri and 9am – 4pm Sat & Sun. Heads of the Valley Trail (Route 46) Steam Train Merthyr Town Centre St Tydfil’s Shopping centre provides a modern semi-covered pedestrian area with a diverse range of places to eat and drink. Various opening times. P Cyfarthfa Retail Park Various retail outlets including eateries. Open 9am – 8pm Mon – Sat, 11am -4pm Sun. MERTHYR TYDFIL M4 Cefn Coed Village A small car park is found on the High Street. Just look for the Church spire as it’s next door to it. The village has places to eat and drink. Looking for more? Open at various times. P visitmerthyr.co.uk Parkwood Outdoors Dolygaer Café For further information contact us at: A great stop at a stunning location for anyone visiting the National Park. You can also pick up needed repair tubes for your bikes. Email: [email protected] Open 9.30 – 5.30. Phone: 01685 725000 Merthyr Section 14 miles P Mail: VisitMerthyr, MerthyrTydfilCounty Borough Council, Tourism Dept. Largely TRAFFIC FREE There’s ample parking throughout the Borough with designated Civic Centre, Castle Street, National Cycle Route 8 car parks. -

DCFW Merthyrcharrette Web.Pdf

“ Whatever you do, try to make it the best in the world.” Report and recommendations arising from the charrette held at Cyfarthfa Castle on Saturday 21st October 2017 Prepared and co-authored by Design Commission for Wales and Geraint Talfan Davies Cyfarthfa Castle and pond, by Penry Williams. Image courtesy of Merthyr Tydfil Libraries Crucible ISBN Number: 978-0-9552657-7-8 CRUCIBLE ‘charrette’ Contents a public meeting or workshop devoted to a concerted effort to solve a problem or plan the design of something. Late Middle English (denoting 02 Introduction a cart or wagon): from French charrette, literally 04 Recommendations ‘cart’; current sense dates from the mid-20th century, possibly with reference to the use of a 05 A: Setting the Scene – Why Merthyr Tydfil? cart in 19th-century Paris to collect architecture 06 The aim of the charrette students’ work on the day of an exhibition. 08 B: Five Challenges ‘crucible’ a vessel made to endure great heat; a melting pot. 11 C: Four bold strands 12 1: A Cathedral for our Industrial Heritage 16 2: Weaving a connected landscape On 21st October 2017 at Cyfarthfa Castle, 3: Beyond Cyfarthfa – Beyond Merthyr 20 Merthyr Tydfil, the Design Commission for Wales 24 4: A year-round framework for events and the Welsh School of Architecture at Cardiff University convened a multi-disciplinary team 26 D: Resources, delivery and management to scope the possibilities within the town and 27 Conclusion surrounding landscape in a bold visioning exercise 28 Appendix A: that sought ways of making of Merthyr’s heritage assets something greater than the sum of its parts, Matrix of potential projects, resources underlining its true international significance. -

Merthyr Tydfil

UK Tentative List of Potential Sites for World Heritage Nomination: Application form Please save the application to your computer, fill in and email to: [email protected] The application form should be completed using the boxes provided under each question, and, where possible, within the word limit indicated. Please read the Information Sheets before completing the application form. It is also essential to refer to the accompanying Guidance Note for help with each question, and to the relevant paragraphs of UNESCO’s Operational Guidelines for the Implementation of the World Heritage Convention, (OG) available at: http://whc.unesco.org/en/guidelines Applicants should provide only the information requested at this stage. Further information may be sought in due course. (1) Name of Proposed World Heritage Site Merthyr Tydfil (2) Geographical Location Name of country/region Wales, United Kingdom Grid reference to centre of site NGR SO 038 068 Please enclose a map preferably A4-size, a plan of the site, and 6 photographs, preferably electronically. page 1 (3) Type of Site Please indicate category: Natural Cultural Mixed Cultural Landscape (4) Description Please provide a brief description of the proposed site, including the physical characteristics. 200 words Merthyr Tydfil occupies a natural basin at the head of the Taf Valley, approximately 20 miles to the north of Cardiff. The surrounding tributary valleys offer the town a perfect aesthetic as well as mineral resource which has shaped the town to its present day form; which remains a potent example of an internationally renowned and permanent reminder of man’s exploitation of the landscape. -

25. WHS Merthyr Tydfil Strategic Flood Consequence Assessment

Merthyr Tydfil County Borough Council June 2018 Merthyr Tydfil Strategic Flood Consequence Assessment Merthyr Tydfil SFCA Merthyr Tydfil County Borough Council Merthyr Tydfil SFCA Document issue details WHS1598 Version Issue date Issue status Prepared By Approved By 1.0 16th March Draft Alexandros Petrakis Paul Blackman 2018 (Consultant) (Technical Director) Philip Weatherley-Hastings (Consultant) 1.1 31st May 2018 Draft Alexandros Petrakis Paul Blackman (Consultant) (Technical Director) Philip Weatherley-Hastings (Consultant) 1.2 1st June 2018 Draft Alexandros Petrakis Paul Blackman (Consultant) (Technical Director) Philip Weatherley-Hastings (Consultant) 1.3 18th June 2018 Draft Alexandros Petrakis Paul Blackman (Consultant) (Technical Director) Philip Weatherley-Hastings (Consultant) 1.4 29th June 2018 Final Alexandros Petrakis Paul Blackman (Consultant) (Technical Director) Philip Weatherley-Hastings (Consultant) For and on behalf of Wallingford HydroSolutions Ltd. This report has been prepared by WHS with all reasonable skill, care and diligence within the terms of the Contract with the client and taking account of both the resources allocated to it by agreement with the client and the data that was available to us. We disclaim any responsibility to the client and others in respect of any matters outside the scope of the above. This report is confidential to the client and we accept no responsibility of any nature to third parties to whom this report, or any part thereof, is made known. Any such party relies on the report at their own risk. The WHS Quality & Environmental Management system is certified as meeting the requirements of ISO 9001:2008 and ISO 14001:2004 providing environmental consultancy (including monitoring and surveying), the development of hydrological software and associated training. -

Overview of the Caerphilly County Borough Area Demographic and Health Data

Overview of the Caerphilly County Borough Area Demographic and Health Data The Caerphilly county borough covers an area stretching from the Brecon Beacons National Park in the north, to Cardiff and Newport in the south. It is bordered to the west by Merthyr Tydfil and Rhondda Cynon Taff, and to the east by Blaenau Gwent and Torfaen local authorities. The area lies at the heart of both the South Wales Valleys and the Cardiff Capital Region. The Caerphilly county borough occupies some 28,000 hectares of the Valleys area of South East Wales. It is a little over 30km long and 17.5km wide and is formed by the valleys of three rivers: the Rhymney, Sirhowy and Ebbw. The county borough is a mixture of urban and rural communities. Three quarters of the county borough is used for agriculture and forestry. The topographical constraints associated with the three valleys presents significant challenges in terms of the relationships and functions of their towns and villages. Few areas within Caerphilly county borough are capable of being economically self-sufficient. There are five principal centres within Caerphilly county borough: Caerphilly, Blackwood, Risca, Bargoed and Ystrad Mynach – Caerphilly being the largest with a population of 33,2361. These centres’ functions are supported by the four local centres of Newbridge, Rhymney, Nelson and Bedwas. These centres function as major employers, retail centres, and providers of services and centres of population. The remaining settlements in the county borough are mainly residential urban areas, although there are a number of remote rural valleys settlements. Overall the county borough comprises of 50 distinct towns and villages, many of which are typical valley settlements and located on the valley floor. -

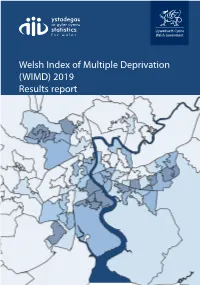

Welsh Index of Multiple Deprivation (WIMD) 2019: Results Report

Welsh Index of Multiple Deprivation (WIMD) 2019 Results report Contact Nia Jones Social Justice Statistics Knowledge and Analytical Services Welsh Government Cathays Park Cardiff CF10 3NQ Tel: 0300 025 4088 Email: [email protected] SFR117/2019 © Crown copyright 2019 All content is available under the Open Government Licence v3.0, except where otherwise stated. Mae’r ddogfen yma hefyd ar gael yn Gymraeg / This document is also available in Welsh Table of Contents 1. What is WIMD? ............................................................................................................. 2 2 WIMD 2019 Overall Index ............................................................................................. 7 3. Income Domain .......................................................................................................... 30 4. Employment Domain .................................................................................................. 39 5. Health Domain ............................................................................................................ 48 6. Education Domain ...................................................................................................... 57 7. Access to Services Domain ........................................................................................ 65 8. Housing Domain ......................................................................................................... 75 9. Community Safety Domain ........................................................................................ -

The Experiences of Basque and Spanish Iron Workers and Their Descendants in Wales from 1900

The Experiences of Basque and Spanish Iron Workers and their Descendants in Wales from 1900 Hola Cymru The Experiences of Basque and Spanish Iron Workers and their Descendants in Wales from 1900 Hola Cymru By Stephen James Murray The Experiences of Basque and Spanish Iron Workers and their Descendants in Wales from 1900 By Stephen James Murray This book first published 2020 Cambridge Scholars Publishing Lady Stephenson Library, Newcastle upon Tyne, NE6 2PA, UK British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library Copyright © 2020 by Stephen James Murray All rights for this book reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the copyright owner. ISBN (10): 1-5275-6231-X ISBN (13): 978-1-5275-6231-8 To my wonderful wife Svetlana, my sorely missed parents Evelyn and John, my warm endearing children Lauren, Joseph and Thomas, to my stalwart and very capable son-in-law Dominic and to my beautiful granddaughter Siân Evelyn. I thank you all for putting up with me. Also, to the memory of Mr Ken Adeva-Vaya con Dios Ken. TABLE OF CONTENTS List of Images, Tables and Illustrations ..................................................... xi Migration Definitions/Terms ................................................................... xiii Abstract .................................................................................................. -

Design & Access Statement

Design & Access Statement Proposed Light Industrial Units, Pant Industrial Estate, Dowlais, Merthyr Tydfi l Preface Contents This A4 size document has been prepared by Powell 1.0 Introduction & Vision Dobson Architects, with input from Amity Planning Ltd. 1.1 Introduction on behalf of the applicant, in support of a full planning 1.2 Vision application for the construction of the creation of 14 light industrial units of sizes ranging from 86m2 to 376m2 and 2.0 Analysis the associated hard and soft landscaping works. 2.1 The Site & Context 2.2 Local Context & Character 2.3 Opportunities & Constraints 3.0 Planning Policy 3.1 Planning History 3.2 Planning Policy 3.3 Planning Overview 3.0 Design Development & Proposals 3.1 Design Development 3.2 Final Design Proposals 3.3 Movement & Access 3.4 Use & Amount 3.5 Character 3.6 Parking 3.7 Refuse Strategy 3.8 Landscape, Ecology 3.9 Drainage 4.0 Community & Access 4.1 Community Access & Safety Courtesy of Mapquest 5.0 Environmental Sustainability Date: 14/02/2020 5.1 Environmental Sustainability Author: IPF Conclusion Revision: A Ref.: 19070 DAS Document Structure Checked: This document demonstrates how the design process and Address: Powell Dobson Cardiff fi nal proposals were appraised against the following criteria: Suite 1F, Building 1, • Analysis – an assessment of the site, physical character Eastern Business Park, Wern Fawr Lane, and local context. Old St Mellons, Cardiff , CF3 5EA • Design Development – outlining how the scheme has Contact Details: tel.: +44 (0)33 33 201 001 developed taking into account the site constraints and email: @powelldobson.com stakeholder comments. -

Understanding Treharris

About the Bevan Foundation The Bevan Foundation is Wales’ most innovative and influential think tank. We develop lasting solutions to poverty and inequality. Our vision is for Wales to be a nation where everyone has a decent standard of living, a healthy and fulfilled life, and a voice in the decisions that affect them. As an independent, registered charity, the Bevan Foundation relies on the generosity of individuals and organisations for its work, as well as charitable trusts and foundations. You can find out more about how you can support us and get involved here: https://www.bevanfoundation.org/support-us/organisations/ Acknowledgements This paper is part of the Three Towns project which is looking at the pre-conditions for growing the foundational economy in Treharris in Merthyr Tydfil, Treherbert in Rhondda Cynon Taf and Cwmafan in Neath Port Talbot. It is funded by the Welsh Government’s Foundational Economy Challenge Fund. Copyright Bevan Foundation Cover image courtesy of Jason Jones of Treharris Author – Lloyd Jones Bevan Foundation 145a High Street Merthyr Tydfil, CF47 8DP January 2021 [email protected] www.bevanfoundation.org Registered charity no 1104191 Company registered in Wales no 4175018 Contents Contents .................................................................................................................................................. 1 Summary ................................................................................................................................................