Canolfannau Cymraeg and Social Networks of Adult Learners of Welsh: Efforts to Reverse Language Shift in Comparatively Non-Welsh-Speaking Communities

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Merthyr Tydfil County Borough Council Planning & Neighbourhood

Merthyr Tydfil County Borough Council Planning & Neighbourhood Services Engineering February 2020 Flood Damage Maps 1) Flood recovery costs spreadsheet 2) Flood damage locations by ward maps 3) Detailed flood damage area maps 3rd May 2020 Ref Location Detail Action/programme Capital / Estimated Cost (£) Revenue 2020-21 2021-22 1 Bedlinog Cemetery Landslide Drainage and Capital 200,000 Road stabilisation work 2 Pant Glas Fawr, Damaged culvert Culvert repairs Capital 70,000 Aberfan 3 Walters Terrace, Damaged culvert Culvert repairs Capital 70,000 Aberfan 4 Chapel Street Landslide Drainage and Capital 80,000 Treodyrhiw stabilisation work 5 Grays Place, Merthyr Collapsed culvert Replace culvert Capital 120,000 Vale 6 Maes y Bedw, Bedlinog Damaged culvert Replace culvert Capital 50,000 7 Nant yr Odyn, Damaged culvert Culvert repairs Capital 50,000 Troedyrhiw 8 Park Place, Troedyrhiw Damaged culvert Culvert repairs Capital 20,000 9 Cwmdu Road, Landslide Drainage and Capital 40,000 Troedyrhiw stabilisation work 10 Fiddlers Elbow, Damaged debris Repair of trash screen Capital 5,000 Quakers Yard screen 11 Pontycafnau River embankment Reinstate embankment Capital 250,000 erosion and scour protection 12 Harveys Bridge, Piers undermined Remove debris with Capital 30,000 Quakers Yard scour protection 13 Taff Fechan Landslide Drainage and Capital 80,000 stabilisation work 14 Mill Road, Quakers River embankment Remove tree and Capital 60,000 Yard erosion stabilise highway 15 Nant Cwmdu, Damaged culvert Culvert repairs Capital 40,000 Troedyrhiw 16 Nant -

Canolfan Llywodraethiant Cymru Paper 5A - Wales Governance Centre

Papur 5a - Canolfan Llywodraethiant Cymru Paper 5a - Wales Governance Centre DEPRIVATION AND IMPRISONMENT IN WALES BY LOCAL AUTHORITY AREA SUPPLEMENTARY EVIDENCE TO THE NATIONAL ASSEMBLY’S EQUALITY, LOCAL GOVERNMENT AND COMMUNITIES COMMITTEE’S INQUIRY INTO VOTING RIGHTS FOR PRISONERS DR GREG DAVIES AND DR ROBERT JONES WALES GOVERNANCE CENTRE AT CARDIFF UNIVERSITY MAY 2019 Papur 5a - Canolfan Llywodraethiant Cymru Paper 5a - Wales Governance Centre ABOUT US The Wales Governance Centre is a research centre that forms part of Cardiff University’s School of Law and Politics undertaking innovative research into all aspects of the law, politics, government and political economy of Wales, as well the wider UK and European contexts of territorial governance. A key objective of the Centre is to facilitate and encourage informed public debate of key developments in Welsh governance not only through its research, but also through events and postgraduate teaching. In July 2018, the Wales Governance Centre launched a new project into Justice and Jurisdiction in Wales. The research will be an interdisciplinary project bringing together political scientists, constitutional law experts and criminologists in order to investigate: the operation of the justice system in Wales; the relationship between non-devolved and devolved policies; and the impact of a single ‘England and Wales’ legal system. CONTACT DETAILS Wales Governance Centre at Cardiff University, 21 Park Place, Cardiff, CF10 3DQ. Web: http://sites.cardiff.ac.uk/wgc/ ABOUT THE AUTHORS Greg Davies is a Research Associate at the Wales Governance Centre at Cardiff University. His PhD examined the constitutional relationship between the UK courts and the European Court of Human Rights. -

Sound Diplomacy Hysbysu Strategaeth Gerdd I Gaerdydd

ADRODDIAD DINAS GERDD SOUND DIPLOMACY HYSBYSU STRATEGAETH GERDD I GAERDYDD Astudiaeth Ecosystem Cerdd ac Argymhellion Strategol Cyflwynwyd gan Sound Diplomacy i Gyngor Caerdydd Mawrth 2019 1 1 Hysbysu strategaeth gerdd i Gaerdydd 1 1. Cyflwyniad 5 1.1 Am y project 7 1.2 Methodoleg 7 1.3 Am yr awduron 8 2. Cyd-destun 9 2.1 Cyd-destun byd-eang 9 2.2 Lle Caerdydd yn niwydiant cerddoriaeth y DU 9 3. Ecosystem Cerdd Caerdydd 11 3.1 Effaith economaidd cerdd Caerdydd 11 3.2 Mapio diwydiant Caerdydd 18 3.3 Canfyddiadau allweddol 19 4. Argymhellion Strategol 33 LLYWODRAETHU AC ARWEINYDDIAETH 33 Y Swyddfa Gerdd 33 1.1 Penodi Swyddog Cerdd 34 1.2 Adeiladu a chynnal cyfeiriadur busnes o’r ecosystem cerdd leol 36 1.3 Datblygu llwyfan i gyfathrebu rhwng preswylwyr lleol a digwyddiadau cerdd 37 Y Bwrdd Cerdd 38 2.1 Sefydlu Bwrdd Cerdd 39 2.2 Creu Is-grŵp Sefydliadau Proffesiynol Bwrdd Cerdd Caerdydd 40 2.3 Creu Is-grŵp Lleoliadau Bwrdd Cerdd Caerdydd 40 2.4 Cryfhau a datblygu cydweithredu rhyng-ddinas pellach 41 Trwyddedau A Pholisïau Sy’n Dda i Gerddoriaeth 44 Sound Diplomacy Ltd +44 (0) 207 613 4271 • [email protected] www.sounddiplomacy.com 114 Whitechapel High St, London E1 7PT, UK • Company registration no: 08388693 • Registered in England & Wales 1 3.1 Symleiddio'r broses drwyddedu ar gyfer gweithgareddau cerdd 44 3.2 Ailasesu gofynion diogelwch ar gyfer lleoliadau a digwyddiadau 45 3.3 Gwella mynediad i ddigwyddiadau cerddoriaeth fyw i gynulleidfaoedd dan oed 46 3.4 Cyflwyno parthau llwytho i gerddorion ar gyfer lleoliadau yng nghanol y -

Nation Radio (Ceredigion)

Analogue Commercial Radio Licence: Format Change Request Form Date of request: 11 June 2020 Station Name: Nation Radio Licensed area and licence Ceredigion number: AL102588 Licensee: Radio Ceredigion Limited Contact name: Martin Mumford Details of requested change(s) to Format Character of Service Existing Character of Service: Complete this section if you are requesting a change to this part of your Format Proposed new Character of Service: Programme sharing and/or co- Current Arrangements: location arrangements Complete this section if you are requesting a change to this part of your Format Proposed new Arrangements: Locally-made hours and/or Current Obligations: local news bulletins Locally-made hours: Complete this section if you are requesting a change to this At least 21 hours per day (must include breakfast and weekend breakfast). part of your Format Local news: No requirement for local news, but Welsh national news must be broadcast at least hourly at peak-time. Proposed new obligations: Locally-made hours: At least 3 hours per day during daytime weekdays Local news: No requirement for local news, but Welsh national news must be broadcast at least hourly during daytime weekdays and peaktime weekends. The holder of an analogue local commercial radio licence may apply to Ofcom to have the station’s Format amended. Any application should be made using the layout shown on this form, and should be in accordance with Ofcom’s published procedures for Format changes.1 Under section 106(1A) of the Broadcasting Act 1990 (as amended), Ofcom -

Ymyl Yr Afon MERTHYR VALE Ymyl Yr Afon MERTHYR VALE Ymyl Yr Afon, Golwg Yr Afan, Merthyr Vale, Merthyr Tydfil CF48 4QQ T: 01685 868 249

PRESENTS Ymyl Yr Afon MERTHYR VALE Ymyl Yr Afon MERTHYR VALE Ymyl Yr Afon, Golwg Yr Afan, Merthyr Vale, Merthyr Tydfil CF48 4QQ T: 01685 868 249 Ymyl Yr Afon MERTHYR VALE Ymyl Yr @lovell_uk /lovellhomes Afon lovellnewhomes.co.uk MERTHYR VALE WELCOME TO A stunning collection of 2, 3 and 4 bedroom homes situated on a former colliery site between Merthyr Vale and Aberfan, with the River Taff curving to the west of the development, the new community will feature attractive tree-lined streets with plentiful areas of open green space. Merthyr Vale Lovell uses sustainable products wherever possible. So not only do our homes help look after the environment, but for homeowners, they also offer excellently insulated properties, minimal maintenance and they stand the test of time. All of our homes are of extremely high quality and specification. Combining carefully considered contemporary design with rigorous build quality, Lovell homes are designed with flair, character and attention to detail. We want your home to be interesting, inviting and individual. LOVELL LIFE Most of all, once you step through the front door, we want you to know you’re home. Oakfield Grange showhome interior Oakfield Grange showhome interior Oakfield Grange showhome interior Every one of the homes we build is built with one crucial extra element: pride. Lovell only builds high-quality homes and we make customer satisfaction our number one priority. This means that you enjoy extraordinary value for money, as well as a superior and distinctive home. At Lovell we believe your home should be more than about the right place at the right price. -

The Insider's Guide to Postgraduate Life In

THE INSIDER’S GUIDE TO POSTGRADUATE LIFE IN CARDIFF 2015 1 Insider’s Guide to Postgraduate Life in Cardiff - Introduction CONTENTS WELCOME P4 P35 LIFE IN CARDIFF BEFORE YOU ARRIVE P5 P37 INFOGRAPHIC MONEY MATTERS P7 P39 SHOPPING ACCOMMODATION P11 P41 EAT, DRINK, PLAY THE UNIVERSITY P19 P43 MY CARDIFF STUDENTS’ UNION P21 P45 EXPLORING THE CITY GRADUATE CENTRE P23 P47 SPORTS OFF CAMPUS SKILLS AND DEVELOPMENT P25 P49 MY CARDIFF NETWORKING P26 P53 OUTSIDE CARDIFF FACILITIES P27 P55 TRANSPORT SPORTS ON CAMPUS P29 P57 CARDIFF BUS MAP SOCIETIES AND OTHER ACTIVITIES P31 P59 CATHAYS CAMPUS MAP SUPPORT SERVICES P33 P61 HEATH PARK CAMPUS MAP The Insider’s Guide is written by past and current Cardiff University Postgraduates. All information is coorect at the time of going to print in March 2015. Insider’s Guide to Postgraduate Life in Cardiff - Introduction 2 Email: [email protected] Tel: +44 (0)29 2087 0084 3 Insider’s Guide to Postgraduate Life in Cardiff - Introduction WELCOME Welcome to the Insider’s Guide to Postgraduate Life in Cardiff. We know there’s a lot to think about when preparing to embark on postgraduate study, so we’ve put together some information to make things a bit easier. Into this neat little guide, we’ve Life in Cardiff is a guide to places poured the very best of our to shop, eat, drink and play, plus knowledge and expertise on money-saving tips and information postgraduate life in Cardiff. Written on ways to get the most out of your by current and former Cardiff Cardiff experience. -

“My” Hero Or Epic Fail? Torchwood As Transnational Telefantasy

“My” Hero or Epic Fail? Torchwood as Transnational Telefantasy Melissa Beattie1 Recibido: 2016-09-19 Aprobado por pares: 2017-02-17 Enviado a pares: 2016-09-19 Aceptado: 2017-03-23 DOI: 10.5294/pacla.2017.20.3.7 Para citar este artículo / to reference this article / para citar este artigo Beattie, M. (2017). “My” hero or epic fail? Torchwood as transnational telefantasy. Palabra Clave, 20(3), 722-762. DOI: 10.5294/pacla.2017.20.3.7 Abstract Telefantasy series Torchwood (2006–2011, multiple production partners) was industrially and paratextually positioned as being Welsh, despite its frequent status as an international co-production. When, for series 4 (sub- titled Miracle Day, much as the miniseries produced as series 3 was subti- tled Children of Earth), the production (and diegesis) moved primarily to the United States as a co-production between BBC Worldwide and Amer- ican premium cable broadcaster Starz, fan response was negative from the announcement, with the series being termed Americanised in popular and academic discourse. This study, drawn from my doctoral research, which interrogates all of these assumptions via textual, industrial/contextual and audience analysis focusing upon ideological, aesthetic and interpretations of national identity representation, focuses upon the interactions between fan cultural capital and national cultural capital and how those interactions impact others of the myriad of reasons why the (re)glocalisation failed. It finds that, in part due to the competing public service and commercial ide- ologies of the BBC, Torchwood was a glocalised text from the beginning, de- spite its positioning as Welsh, which then became glocalised again in series 4. -

Reports and Financial Statements 2013-14 Layout 1

2013/14 Reports and Financial Statements for the year ended 31 March 2014 Charity number 1034245 General Activites Account Contents Annual Report: • Trustees’ Annual Report 03 o Annual Governance Statement 06 • Environmental report 43 • Remuneration report 47 • Statement of Council’s and the Accounting Officer’s responsibilities 49 The Certificate and Report of the Auditor General for Wales to the Arts Council of Wales 50 Financial statements: • Statement of financial activities 52 • Balance sheet 53 • Cash flow statement 54 • Notes forming part of the financial statements 55 Annex to the Annual Report (not forming part of the financial statements): • Grants 80 Arts Council of Wales is committed to making information available in large print, Braille, audio and British Sign Language and will endeavour to provide information in languages other than Welsh or English on request. Arts Council of Wales operates an equal opportunities policy. Front Cover: Theresa Nguyen, Gold Medal for Craft and Design at Y Lle Celf, National Eisteddfod of Wales 2013 (image: Dewi Glyn Jones) BIANCO, NoFit State (image: Richard Davenport) Annual Report for the year ended 31 March 2014 Trustees’ Annual Report Reference and administrative details Trustees Council Members who served since 1 April 2013 were: Attendance at meetings during 2013/14 Audit Capital Remuneration Council Committee Committee Committee1 Number of meetings held: 6550 Professor Dai Smith, (c) 6 Committee Chair Chairman n/a Dr Kate Woodward, (d) 3 Vice-chairman Emma Evans (a) 5 Committee Chair -

Music Venue Trust Response to Music Industry in Wales Inquiry

Music Venue Trust response to Music Industry in Wales Inquiry 1. About Music Venue Trust Music Venue Trust is a registered charity which acts to protect, secure and improve Grassroots Music Venues in the UK. 1 Music Venue Trust is the representative body of the Music Venues Alliance 2, a network of over 500 Grassroots Music Venues in the UK. A full list of the 34 Music Venues Alliance Wales members is provided at Annex A. 2. Grassroots Music Venues in 2019 A. A nationally and internationally accepted definition of a Grassroots Music Venue (GMV) is provided at Annex B. This definition is now in wide usage, including by the UK, Scottish and Welsh Parliaments. 3 GMVs exhibit a specific set of social, cultural and economic attributes which are of special importance to communities, artists, audiences, and to the wider music industry. Across sixty years, this sector has played a vital research and nurturing role in the development of the careers of a succession of UK musicians, for example The Beatles (The Cavern, Liverpool) through The Clash (100 Club, London), The Undertones (The Casbah, Derry), Duran Duran (Rum Runner, Birmingham), Housemartins (Adelphi, Hull), Radiohead (Jericho Tavern, Oxford), Idlewild (Subway, Edinburgh). All three of the UK’s highest grossing live music attractions in 2017 (Adele, Ed Sheeran, Coldplay) commenced their careers with extensive touring in this circuit. 4 In Wales, GMVs have played a central role in kickstarting the careers of The Manic Street Preachers (TJs, Newport), Supper Furry Animals (Clwb Ifor Bach, Cardiff), The Joy Formidable, (Central Station, Wrexham), Gruff Rhys (Neuadd Ogwen, Bangor), Funeral For A Friend (Hobo’s Bridgend), Skindred (Sin City, Swansea). -

Deprivation and Imprisonment in Wales by Local Authority Area

DEPRIVATION AND IMPRISONMENT IN WALES BY LOCAL AUTHORITY AREA SUPPLEMENTARY EVIDENCE TO THE NATIONAL ASSEMBLY’S EQUALITY, LOCAL GOVERNMENT AND COMMUNITIES COMMITTEE’S INQUIRY INTO VOTING RIGHTS FOR PRISONERS DR GREG DAVIES AND DR ROBERT JONES WALES GOVERNANCE CENTRE AT CARDIFF UNIVERSITY MAY 2019 ABOUT US The Wales Governance Centre is a research centre that forms part of Cardiff University’s School of Law and Politics undertaking innovative research into all aspects of the law, politics, government and political economy of Wales, as well the wider UK and European contexts of territorial governance. A key objective of the Centre is to facilitate and encourage informed public debate of key developments in Welsh governance not only through its research, but also through events and postgraduate teaching. In July 2018, the Wales Governance Centre launched a new project into Justice and Jurisdiction in Wales. The research will be an interdisciplinary project bringing together political scientists, constitutional law experts and criminologists in order to investigate: the operation of the justice system in Wales; the relationship between non-devolved and devolved policies; and the impact of a single ‘England and Wales’ legal system. CONTACT DETAILS Wales Governance Centre at Cardiff University, 21 Park Place, Cardiff, CF10 3DQ. Web: http://sites.cardiff.ac.uk/wgc/ ABOUT THE AUTHORS Greg Davies is a Research Associate at the Wales Governance Centre at Cardiff University. His PhD examined the constitutional relationship between the UK courts and the European Court of Human Rights. He is currently working on the ESRC project, Between Two Unions, which examines the implications of Brexit for the UK’s territorial constitution. -

Menter Bro Morgannwg Welsh Language Profile 2016

Menter Bro Morgannwg Welsh Language Profile 2016 May 2016 www.Cwmni2.cymru www.nico.cymru Menter Bro Morgannwg Welsh Language Profile 1 1. Introduction This profile examines the position of the Welsh language in the Vale of Glamorgan, and the way that The Vale of Welsh speakers in the area use the Welsh language in Glamorgan has their communities. 13,189 Welsh The aim is to look at the context of the Welsh speakers, language in the area today so that ways of increasing which is 10.8% opportunities for Welsh speakers to use the language of the can be considered. It will help the Menter to plan population strategically and operate as an influential partner as organisations are faced with meeting the statutory requirements in relation to the Welsh language in their areas. This profile is based on the 2011 Census statistics; the Welsh Government’s 2013-15 Language Use Survey; the Welsh Government Pupil Level Annual School Census 2015; Use of the Welsh Language in the Community: Research Study, Bangor University 2015; with reference also to the results of a survey held in Mentrau areas in south east Wales during February and March 2016, with 733 responses. Menter Bro Morgannwg Welsh Language Profile 2 Contents 1. Introduction ............................................................ 1 2. Context ................................................................... 3 3. Welsh speakers in the Vale of Glamorgan ............... 9 4. Welsh Language Use ............................................. 13 i In the home ....................................................... 16 ii The Community ................................................ 18 iii Education ........................................................ 20 Iv Learning Welsh ................................................ 24 v Workplace ........................................................ 26 vi Public, private and voluntary bodies ................ 28 vii Social Media .................................................... 30 5. Conclusion ............................................................ 31 6. -

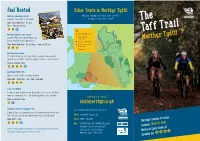

The Taff Trail Is Just One of a Series of Trails Running Right Rivals the Best in the World

Feel Rested Other Trails in Merthyr Tydfil Aberfan Community Centre Merthyr has plenty of other trails on offer, Located in the centre of the village. so why not try one of these? The Open: 8am-8pm Mon - Fri and 9am – 4pm Sat & Sun. P Key Taff Trail (Route 8) Taff Trail Merthyr Tydfil Leisure Centre Trevithick Trail Located in Merthyr’s Leisure Village, just (Route 477) Merthyr Tydfil a short walk from the town centre. Celtic Trail (Route 4) Open: 8am-8pm Mon - Fri and 9am – 4pm Sat & Sun. Heads of the Valley Trail (Route 46) Steam Train Merthyr Town Centre St Tydfil’s Shopping centre provides a modern semi-covered pedestrian area with a diverse range of places to eat and drink. Various opening times. P Cyfarthfa Retail Park Various retail outlets including eateries. Open 9am – 8pm Mon – Sat, 11am -4pm Sun. MERTHYR TYDFIL M4 Cefn Coed Village A small car park is found on the High Street. Just look for the Church spire as it’s next door to it. The village has places to eat and drink. Looking for more? Open at various times. P visitmerthyr.co.uk Parkwood Outdoors Dolygaer Café For further information contact us at: A great stop at a stunning location for anyone visiting the National Park. You can also pick up needed repair tubes for your bikes. Email: [email protected] Open 9.30 – 5.30. Phone: 01685 725000 Merthyr Section 14 miles P Mail: VisitMerthyr, MerthyrTydfilCounty Borough Council, Tourism Dept. Largely TRAFFIC FREE There’s ample parking throughout the Borough with designated Civic Centre, Castle Street, National Cycle Route 8 car parks.